My short story ‘The cabin’ is about a young Inupiaq teenager who encounters something strange while trapping.

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

- Debbie on Social Media

- 2024 American Indian Literature Award Medal Acceptance Speeches

- Native Removals in 2025 by US Government

Wednesday, October 14, 2020

Highly Recommended: The Cabin, by Nasuġraq Rainey Hopson

Thursday, October 08, 2020

Highly Recommended: APPLE (SKIN TO THE CORE) by Eric Gansworth

Monday, October 12 is Indigenous Peoples' Day. There will be many virtual events taking place. Top of my list is the one from Arizona State University. Eric Gansworth will open their day of events. When you click on through to register for his lecture (at noon, Central Time) you will see that Gansworth was selected to deliver the 2020 lecture in the prestigious Simon Ortiz Red Ink Indigenous Speaker Series. People in Native studies or who study the writing and scholarship of Native people will recognize names of people who have given that lecture. In the field, being selected to give that lecture has tremendous significance. Videos for most of the talks are available at the site. If you are new to your work in learning about Native writing, make time to watch and study all of them!

Gansworth will be talking about his new book, Apple (Skin to the Core). Across the hundreds of Native Nations, our life experiences differ. Census information has shown that about half of us grow up in suburban or urban areas. I'm glad to see books set in those spaces.

Some of us grew up on our homelands or on reservations. Native-authored books for children and young adults that reflect a reservation sense-of-place with the integrity that Gansworth brings to his writing, are rare. On Indigenous Peoples Day, I'll be giving a talk, too. My audience will be Pueblo peoples. I expect a large segment of the audience to be people who are living on their Pueblo homelands. And so, I'm emphasizing books like Apple (Skin to the Core) that will speak directly to a reservation-based experience. Of course, everyone should read it and Gansworth's other two books, If I Ever Get Out of Here and Give Me Some Truth.

As I read through his memoir, I linger over some of what I read... I want to tell you about this poem, or what I see on that page, but that's not the thrust of this post. A review is forthcoming. Today, I celebrate the gifts that Eric Gansworth gives to us, in every word he writes, in each poem, story, and book.

Eric Gansworth (Sˑha-weñ na-saeˀ), a writer and visual artist, is an enrolled member of the Onondaga Nation. He was raised at the Tuscarora Nation, near Niagara Falls, New York. Currently, he is a Professor of English and Lowery Writer-in-Residence at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York.

Thursday, October 01, 2020

Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

Editors Note: This post was created as a one-page document that would fit into a single page. It is also available as a pdf. If you have trouble opening or downloading the pdf, write to us directly (see the "Contact" tab for Debbie's email address). A one-pager was hard to do! We wanted to add resources for each of the ten points. Instead, we'll be adding resources in the comments section. We encourage you to share the link to this post and the pdf with others but do not insert Tips for Teachers in something you are selling! We created this as a free resource. If you see someone selling it, please let us know.

Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

Prepared by Debbie Reese (Nambé Owingeh) and Jean Mendoza (White)

American Indians in Children’s Literature

(1) “American Indian” and “Native American” are broad terms that describe the Native Nations of peoples who have lived on North America for thousands of years. Recently, “Indigenous” has come into use, too (note: always use a capital letter for Indigenous). Many people use the three terms interchangeably but educationally, best practice is to teach about and use the name of a specific Native Nation.

(2) There are over 500 sovereign Native Nations that have treaty or legal agreements with the United States. Like any sovereign nation in the world, they have systems of government with unique ways of selecting leaders, determining who their citizens are (also called tribal members), and exercising jurisdiction over their lands. That political status distinguishes Native peoples from other minority or underrepresented groups in the United States. Native peoples have cultures (this includes unique languages, stories, religions, etc.) specific to who they are, but their most important attribute is sovereignty. Best practice—educationally—is to begin with the sovereignty of Native Nations and then delve into unique cultural attributes (languages, religions, etc.)

(3) There is a tendency to talk, speak, and write about Native peoples in the past tense, as if they no longer exist. You can help change that misconception by using present tense verbs in your lesson plans, and in your verbal instruction when you are teaching about Native peoples.

(4) Another tendency is to treat Native creation and traditional stories like folklore or as writing prompts, or to use elements within them as the basis for art activities. Those stories are of religious significance to Native peoples and should be respected in the same ways that people respect Bible stories.

(5) In many school districts, instruction and stories about Native peoples are limited to Columbus Day or November (Native American month) or Thanksgiving. Native peoples are Native all year long and information about them should be included year-round.

(6) Native peoples of the 500+ sovereign nations have unique languages. A common mistake is to think that “papoose” is the Native word for baby and that “squaw” is the word for woman. In fact, each nation has its own word for baby and woman, and some words—like squaw—are considered derogatory. We also have unique clothing. Some use feathered headdresses; some do not.

(7) To interrupt common misconceptions, develop instructional materials that focus on a specific nation—ideally—one in the area of the school where you teach. Look for that nation’s website and share it with your students. Teach them to view these websites as primary sources. Instead of starting instruction in the past, start with the present day concerns of that nation.

(8) To gain an understanding of issues that are of importance to Native peoples, read Native news media like Indian Country Today, Indianz, and listen to radio programs like “Native America Calling.”

(9) The National Congress of American Indians has free resources online that can help you become more knowledgeable. An especially helpful one is Tribal Nations and the United States: An Introduction, available here: http://www.ncai.org/about-tribes.

(10) Share what you learn with your fellow teachers!

__________________________________________________________

© American Indians in Children's Literature.

Tuesday, September 29, 2020

Highly Recommended: "What's an Indian Woman to Do?" in WHEN THE LIGHT OF THE WORLD WAS SUBDUED, OUR SONGS CAME THROUGH

The first three lines in Rendon's poem, "What's an Indian Woman to Do?" are these:

what's an indian woman to do

when the white girls act more indian

than the indian women do?

"Poems like Marcie Rendon's playful "What's an Indian Woman to Do?" both worry the edges of mixed identity and strongly claim Indigenous belonging."

Because we respect indigenous nations' right to determine who is a tribal member, we have included only indigenous-nations voices that are enrolled tribal members or are known and work directly within their respective communities. We understand that this decision may not be a popular one. We editors do not want to arbitrate identity, though in such a project we are confronted with the task. We felt we should leave this question to indigenous communities.

And yet, indigenous communities are human communities, and ethics of identity are often compromised by civic and blood politics. The question "Who is Native?" has become more and more complex as culture lines and bloodlines have thinned and mixed in recent years. We also have had to contend with an onslaught of what we call "Pretendians," that is, nonindigenous people assuming a Native identity. When individuals assert themselves as Native when they are not culturally indigenous, and if they do not understand their tribal nation's history or participate in their tribal nation's society, who benefits? Not the people or communities of the identity being claimed.

MARCIE RENDON (1952–), Anishinaabe, an enrolled member of the White Earth Nation, is a poet, playwright, and community activist. Rendon’s work includes two novels, most recently Girl Gone Missing (2019), as well as four children’s nonfiction books. She received the Loft Literary Center’s 2017 Spoken Word Immersion Fellowship. She is a producer and creative director at the Raving Native Theater in Minnesota.

Highly Recommended! THE SEA IN WINTER by Christine Day

Jean and I both read Christine Day's The Sea in Winter and are thrilled by what Day has written! A review is forthcoming, but I wanted to give you all a heads-up. Day's book comes out on January 5, 2021. Pre-order it! And check out her website. She's an enrolled citizen of the Upper Skagit tribe.

Here's the book description, from Day's website:

It’s been a hard year for Maisie Cannon, ever since she hurt her leg and could not keep up with her ballet training and auditions.

Her blended family is loving and supportive, but Maisie knows that they just can’t understand how hopeless she feels. With everything she’s dealing with, Maisie is not excited for their family midwinter road trip along the coast, near the Makah community where her mother grew up.

But soon, Maisie’s anxieties and dark moods start to hurt as much as the pain in her knee. How can she keep pretending to be strong when on the inside she feels as roiling and cold as the ocean?

I read an advanced reader's copy in August and tweeted my excitement about it. The Sea In Winter is the first book I saw with the Heartdrum logo on the spine. In that tweet, I said:

Honestly, I'm trembling a bit as I hold an ARC of Christine Day's THE SEA IN WINTER in my hands, and gaze at the Heartdrum logo on the spine, created by Nasuġraq Rainey Hopson. Congratulations, and thank you, @CynLeitichSmith and all those who brought this imprint into being.

And I shared a close up photo of the logo:

I passed my copy of the book over to Jean. She's spent a lot of time in that area and will be doing the review essay. Do order a copy, though, right now!

Saturday, September 19, 2020

Not Recommended: Conrad Richter's THE LIGHT IN THE FOREST

In the acknowledgements, Richter says he was struck by stories of white captives who had been returned to their white families, but who wanted to run away to rejoin the Indian home where they'd lived.

As a small boy, Richter wanted to run away to live "among the savages."

The acknowledgement is romantic (and stereotypical) in tone. It says Indians were repelled by American ideals and restrained manner. I don't know what ideals Richter had in mind but "restrained" on the heels of "savages" might be a hint of what is to come as I read the book.

The main character is 15. He's white and has been living with Indians as an adopted son since he was 4. The village has received word that they must give up their white prisoners.

He is shocked that it includes him.

Cuyloga (the Indian man who adopted him) had "said words that took out his white blood and put Indian blood in its place." He was thereafter called True Son.

I'm always curious as to how a writer comes up with a Native name for a character. I looked up Cuyloga...

... and got hits to Sparknotes and Cliffsnotes and gradesaver and enotes and quizlet and coursehero.... all of which tell me the book is used a lot in schools.

I think we're meant to think that "Cuyloga" is a Lenape word. The people in this village would probably speak Lenape. But Cuyloga gave this white child he adopted an English name: "True Son." I wonder if Richter will use "True Son" throughout, or if he'll use a Lenape name?

In the first para of ch 1, we learn that Cuyloga taught True Son to "endure pain." True Son holds a hot stone from the fire "on his flesh to see how long he could stand it." In winter, Cuyloga sat smoking on the bank while True Son sat in the icy river till Cuyloga said ok.

True Son doesn't want to be returned to the whites, so he blackens his face (why?!) and hides in a hollow tree. But, Cuyloga finds him. True Son is "tied up in his father's cabin like some prisoner to be burned at the stake."

Burned at the stake?! Again,

Cuyloga takes True Son to the soldiers nearby. True Son resists, which embarrasses Cuyloga. He leaves and True Son imagines their village and its "warriors and hunters, squaws, and the boys, dogs and girls he had played with."

Squaws?

I've read enough of Richter's THE LIGHT IN THE FOREST to know I will be asking people not to use it. It is old, stereotypical, and there are better choices. If the goal is to study conflicts between Native and White people, Erdrich's BIRCHBARK HOUSE is much better!

Wednesday, September 09, 2020

Reckoning with A CHILD'S GARDEN OF VERSES

Recently, a reader of AICL wrote to me (Debbie) to say they'd been looking through editions of Robert Louis Stevenson's A Child's Garden of Verses in their library. They had seen my 2017 post about depictions of Native peoples in various editions.

They sent me photos of the poem, "Travel." Here's the edition illustrated by Tasha Tudor:

In Tudor's edition I circled a line. Here's the full verse:

Where are forests, hot as fire,

Wide as England, tall as a spire,

Full of apes and cocoa-nuts

And the negro hunters' huts;

Wednesday, August 19, 2020

Some Things We're Learning: More about IPH4YP

Monday, August 17, 2020

The Monster That Eats Villages: White Anti-Indigenous Raceshifting in Canada

Darryl Leroux's Distorted Descent: White Claims to Indigenous Identity (University of Manitoba Press, 2019) takes a close look at a particular set of non-Native people who claim Native identity.

To be clear: there are peoples with legitimate Métis identity. If what I say here is incorrect in any way, I hope Métis readers will jump in and correct me. Their homelands mainly are considered to be in what are currently known as Canada's Western provinces, and parts of the northern US. Their culture and language are based on kinship relations between early French-speaking settlers and the Plains Cree, Salteaux, Assiniboine, and Dene peoples. Métis in French is equivalent to the English word "mixed." According to what I've read about the language (Michif), it combines elements of French, Cree, and some Ojibwe, and has a complex grammar and syntax. It is considered an endangered language.

Instead, these raceshifters tend to be openly contemptuous of Indigenous peoples. They hold (one might say they cherish) negative stereotypes and blatantly white supremacist beliefs about First Nations. They have no interest in traditions (unlike white New-Agers in the US), or in revitalizing endangered Native languages. French is the only language they express concern about preserving.

Their sole interest lies in Native rights -- specifically, in getting those rights for themselves. Hunting and fishing rights are particularly important to a number of the raceshifters. In fact, Leroux found, hunting and fishing organizations are where a great many of them got to know each other. Some have met through white-rights groups. Leroux found them openly, actively committed to opposing Indigenous land and territorial negotiations. They make no secret of these goals -- not in online forums, in court, nor in their conversations with Leroux. You might say they are deeply and proudly committed to making sure the part of the world they're in stays as colonized as possible.

They have no real understanding of the background of the legal relations between Canada and First Nations and Métis, nor do they care about it. What they know is that the First Nations people seem to have some things they feel should be theirs (e.g., the right to hunt or fish freely in certain places over which Indigenous people -- with good reason -- have jurisdiction). They saw that the quickest way to get those things would be to claim Indigenous ancestry.

They can't simply claim that Great-Grandma was an Ojibwe princess; that doesn't work any more. Instead, Leroux found, they use circuitous genealogical and legal-system maneuvers. They comb through genealogies -- readily available partly because of the long-standing French Canadian interest in European heritage. They manage to trace their lineages to a few specific 17th-century women. Those women's birth records, marriage records, etc. indicate that they were French immigrants to what is now called Canada. But (sometimes with the help of genealogists of questionable repute) the raceshifters concoct Indigenous identities for the women, "discovering" that this or that ancestor from the 1600s was Ojibwe, Wendat, or some other Native identity --even when records clearly show that the supposed forebear was born in France, to French parents. Often with encouragement from others on online forums, aspiring "Eastern Métis" sidestep or ignore or flat-out lie about evidence that in fact their ancestry is purely European. Some have gone so far as to claim that there were obviously TWO persons named X in a given area in the 1600s, and THEIR ancestor of that name was Indigenous.

All of this might be comical if the raceshifters didn't pose a threat to the political well-being of First Nations/Métis peoples. The (white) "Eastern Métis" number in the thousands. One of their manufactured "tribal" identities has some 20,000 members. There may be enough of them to turn the heads of elected officials who need Métis votes. Leroux recounts a situation in which they worked hard to mobilize local residents against the Innu and Mi'kmaq First Nations. Raceshifters may even get elected to office themselves, with direct power over the interpretation of First Nations' rights.

It seemed to me that in those dreams, the faux-Métis were the monsters -- like the evil Iya in Dovie's story, they disguise themselves in order to destroy and devour. Their unapologetic contempt for actual First Nations and Métis peoples, their self-justification, their racism, their trickery, and their ultimate goals, are infuriating and terrifying. Now I read Leroux's book in the full light of day, in small doses. Horror has never been a good genre for me, and Distorted Descent is, to me, a real-life, research-based horror story.

Thursday, August 13, 2020

Historical Fiction by Native Writers

I Am Not a Number by Jenny Kay Dupuis (Anishinaabe, Nipissing First Nation) and Kathy Kacer. Published in 2016 by Second Story Press.

At the Mountain's Base by Traci Sorell (enrolled citizen of the Cherokee Nation). Illustrations by Weshoyot Alvitre (Tongva, Cahuilla, Chumash, Spanish & Scottish). Published in 2019 by Kokila Press.

Saltypie by Tim Tingle (Choctaw). Published in 2010 by Cinco Puntos Press.

Wednesday, July 15, 2020

Illustrations in LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE

I've done a lot of writing about the books and Wilder. I am not a fan. I think they've got many problems that are not seen as such by most readers.

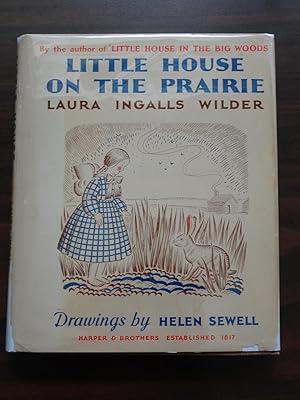

I've pulled a lot of my materials on Wilder out, and thought some AICL readers might be interested in seeing the original illustrations done by Helen Sewell, compared to what Garth Williams did. I'm using a hardcover copy of the Sewell book. I don't have the book jacket, but for your reference, it looked like this:

Most of the books that have illustrations by Williams have the cover shown below (a notable exception was one that showed a photo of a little girl meant to be Laura).

So--here you go! I'll number the side-by-side photos as I place them here. If you want to, submit comments below and refer to the photo number when you refer to a specific one. Apologies for the rough quality of the photos! I don't have lighting or equipment to do a professional-looking presentation of the books. Today you'll see photos of the cover thru end of the first chapter. I'll add others as time permits.

As you'll see when you scroll down, I'm trying to match text on page whenever either book has an illustration. Why did Sewell make decisions she did? Or Williams? How much autonomy did they have? How much was determined by Wilder? Or by the book editor? Or by the art department?

I welcome your thoughts and if you can point to writings about any of this, please do! And if you use these for your own writing, please cite me (Debbie Reese) and AICL.

COVER (on left is Sewell; on right is Williams).

#1

TITLE PAGES

#2

#3

TABLE OF CONTENTS

#4

ANOTHER TITLE PAGE

#5

CHAPTER 1: GOING WEST

#6

#7

#8

#9

My only observations at the moment for chapter one are that the Williams edition has more illustrations than the Sewell one. Four illustrations of the wagon versus one illustration of the girls clinging to their rag dolls. Quite different in tone, isn't it?

Update: July 29, 2020--Back to add photos of illustrations in chapter two, "Crossing the Creek"

#10

#11

#12

Observations: The Sewell edition has no illustrations in chapter 2. The Williams one has illustrations on four pages. Three of the four have the wagon, and Williams is bringing a visual emotional tone of danger and loss to the story.

Tuesday, July 07, 2020

Open Letter to Roger Goodell, from American Indians in Children's Literature

Roger Goodell, Commissioner

National Football League

280 Park Avenue

New York, NY 10017

Dear Mr. Goodell,

We write to you today as the editors of American Indians in Children's Literature. Established in 2006, AICL is widely recognized in Education, Children's Literature, and Library Science for its analyses of representation of Native peoples in children's books.

We hold PhDs in Curriculum and Instruction from the University of Illinois and we have taught in public and private schools, and in universities and colleges. A primary emphasis of our work as educators is helping others recognize stereotypes of Native peoples in children's books. We believe that the Washington NFL team mascot enables similar mascots in professional and collegiate sports and in K-12 schools. As the images below demonstrate, stereotypes in children's books look a lot like the mascots. There are many examples like this:

We agree with the requests put forth in the letter from Suzan Shown Harjo, Amanda Blackhorse, and the growing list of Native leaders who are signing their letter. The requests are:

- Require the Washington NFL team (Owner: Dan Snyder) to immediately change the name R*dsk*ns, a dictionary defined racial slur for Native Peoples.

- Require the Washington team to immediately cease the use of racialized Native American branding by eliminating any and all imagery of or evocative of Native American culture, traditions, and spirituality from their team franchise including the logo. This includes the use of Native terms, feathers, arrows, or monikers that assume the presence of Native American culture, as well as any characterization of any physical attributes.

- Cease the use of the 2016 Washington Post Poll and the 2004 National Annenberg Election Survey which have been repeatedly used by the franchise and supporters to rationalize the use of the racist r-word name. These surveys were not academically vetted and were called unethical and inaccurate by the Native American Journalist Association as well as deemed damaging by other prominent organizations that represent Native Peoples. The NFL team must be held accountable to the various research studies conducted by scientists and scholars which find stereotypical images, names and the like are harmful to Native youth and the continued progress of the wellbeing of Native Peoples.

- Cease the use of the offensive, racial slur name “R*dsk*ns” immediately, and encourage journalists, writers and reporters to use the term in print only by using asterisks "R*dsk*ns" and to refer to the term verbally as the “r-word”.

- Ban all use of Native imagery, names, slur names, redface, appropriation of Native culture and spiritually as well as violence toward Native Peoples from the League.

- Apply the NFL’s “zero tolerance” for on-field use of racial and homophobic slurs to all races and ethnic groups, especially Native Peoples.

- Complete a full rebranding of the Washington team name, logo, mascot, and color scheme, to ensure that continuing harm is not perpetuated by anyone.

As parents of Native children, we have first-hand knowledge of how mascots impact Native lives. Research done by Davis, Delano, Gone, and Fryberg demonstrates the need to let go of these mascots. You may already be aware that the American Psychological Association (APA) recommended retiring all "American Indian" mascots and imagery in its 2005 resolution on the topic, as did the American Sociological Association (ASA) in 2007.

The time for decisive action is long past, and we hope you will take that action, now.

Sincerely,

Debbie Reese

Tribally enrolled: Nambé Pueblo

Editor, American Indians in Children's Literature

Jean Mendoza

Editor, American Indians in Children's Literature