Remember your birth, how your motherstruggled to give you form and breath.You are evidence of her life,and her mother's, and hers.

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

- Debbie on Social Media

- 2024 American Indian Literature Award Medal Acceptance Speeches

- Native Removals in 2025 by US Government

Tuesday, March 21, 2023

Highly Recommended: REMEMBER by Joy Harjo, illustrated by Michaela Goade

Wednesday, May 12, 2021

Highly Recommended! I SANG YOU DOWN FROM THE STARS, written by Tasha Spillett-Sumner; illustrated by Michaela Goade

Family and friends came from near and far to welcome you.One by one, they held you and greeted you.

Monday, January 25, 2021

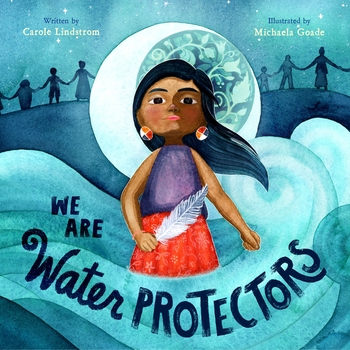

Carole Lindstrom and Michaela Goade--Two Tribally Enrolled Women--Made History Today, for WE ARE WATER PROTECTORS

Two tribally enrolled women made history today when the American Library Association awarded the Caldecott Medal to their book, We Are Water Protectors. Prior to this, the only Native person to be selected for recognition from the Caldecott was Velino Herrera of Zia Pueblo. In 1942, his illustrations for Ann Nolan Clark's In My Mother's House won a Caldecott Honor. Clark was a white woman who taught in Native schools.

Carole Lindstrom, the author of We Are Water Protectors, is tribally enrolled at Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, and Michaela Goade, the illustrator, is Tlingit, a member of the Kiks.ådi Clan.

Published in 2020 by Roaring Book Press its text and illustrations carry tremendous meaning for Native people around the world who are active in ongoing work to stop exploitation. Here's a screen capture of the livestream announcement earlier today (Jan 25). It shows the gold seal on the cover of the book:

Some will remember the photos of a young person kneeling before a line of law enforcement officers, holding an eagle feather in front of them. The photos are taken from behind. For the book cover, Goade shows us a young person from the front.

Behind her, you see a line of people holding hands. You'll likely remember photos from Standing Rock that show Native people holding hands to ward off law enforcement.

The last two pages of the book are a double-page spread of Indigenous people. Some of you went to the marches held across the country. Elders and children were there. You will remember that some of us were in traditional clothes, and some of us were holding signs. Carole and I were together for the march in Washington DC on March 20, 2017. It looked a lot like this:

Because We Are Water Protectors won the Caldecott Medal, children around the world will read about Water Protectors, for generations to come. Kúdaa, Carole and Michaela, for giving this book to all of us.

Water is Life

Mini Wiconi

#NoDAPL

All Nations

Protect the Sacred

Stand with Standing Rock

****

Articles in news media:

School Library Journal: A Grateful Michaela Goade Makes Caldecott History

Indian Country Today: The First Indigenous Caldecott Medal winner

Thursday, December 05, 2019

Not Recommended: ENCOUNTER by Brittany Luby and Michaela Goade

In the end, we decided we cannot recommend it.

We hope to share our conversations about Encounter with AICL's readers but for now, we are giving you a short version of our thoughts on the book. The publisher's description of the book is below, followed by our respective thoughts on the book.

A powerful imagining by two Native creators of a first encounter between two very different people that celebrates our ability to acknowledge difference and find common ground.

Based on the real journal kept by French explorer Jacques Cartier in 1534, Encounter imagines a first meeting between a French sailor and a Stadaconan fisher. As they navigate their differences, the wise animals around them note their similarities, illuminating common ground.

This extraordinary imagining by Brittany Luby, Professor of Indigenous History, is paired with stunning art by Michaela Goade, winner of 2018 American Indian Youth Literature Best Picture Book Award. Encounter is a luminous telling from two Indigenous creators that invites readers to reckon with the past, and to welcome, together, a future that is yet unchartered.

Debbie's thoughts:

When I first learned of the book, my thoughts turned to Thanksgiving picture books that show Pilgrims and Indians (sometimes Wampanoags) meeting each other. In particular, Rockwell's Thanksgiving Day came to mind. In it, the children are doing a reenactment of the Pilgrim's landing. One child playing the part of a Pilgrim is thankful that the Pilgrims were "greeted kindly by the Wampanoag people who shared their land with them." Another child, playing the part of a Wampanoag, is thankful that the Pilgrims are peaceful. Another, playing the part of a Wampanoag leader, talked about how the Wampanoag and Pilgrim people shared a feast that autumn day. It is, in tone, idyllic.

Rockwell's book came out in 1999 but ones like it come out every year. Writers and illustrators, it seems to me, keep trying to tell that same story. Each year there is pushback to that story. On social media, people replied to tweets and posts from teachers who showed their classes of children, reenacting that "first Thanksgiving." It seems people in the US are determined to turn that idyllic story into the truth. And so--when I first saw Encounter--I was afraid that it would be celebrated for its storyline, and because of its author and illustrator. Over time, my fears were realized. It got starred reviews, was featured on NPR, and it is now appearing on Best of 2019 book lists.

It definitely appeals to White readers, but I could not--and cannot--imagine handing the book to a Native child or Native family. I'm glad for the visibility that it brings to both, Luby and Goade, and I hope that it leads to more opportunities with a major publisher. I don't think any library or home needs imagined stories like this one. I think we need ones that are honest tellings of history.

Jean's thoughts:

The Author's Reflection and the Historical Note in the back of the book help explain what Brittany Luby is going for with Encounter: an intentional contrast with actual events, a thought-provoking counter-story. So I gave a lot of attention to how it felt to read and re-read the story and the author's comments, in light of all that still sits with me after Debbie and I adapted An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States for Young People. What would it mean to kids -- Native kids and non-Native -- that this story about an imaginary innocent Native/white friendship is so far from what really happened?

Reading Encounter at this point in life turned out to be work. I'm white; my husband and our kids are Mvskoke Creek. I'm also of a generation that pretty much drowned in "cowboys/cavalry & Indians" imagery, and I had just spent several years immersed in Indigenous history. I found that I did a lot of mental and emotional processing about Encounter. No need to go into all that, but it made me see that sharing it with kids would be complicated. Before long, we could tell the book was getting popular, and would inevitably be shared with lots of children, probably plucked off bookshelves for friendship-affirming read-alouds.

Debbie mentioned (above) those persistent Thanksgiving myths. "First contacts" between Europeans and Indigenous peoples are also heavily mythologized as part of the grand American narrative. That's what schooling tells us about US history, over decades of our lives, and it's hard to un-do. Some people don't want to undo it. (Many Native families provide the less shiny reality for their children, though.)

We know, given the make-up of the school and library professions, it'll be mostly non-Native professionals who read or recommend Encounter to their students or patrons. So for a while my head was full of caveats. The adults would need to be deeply intentional & thoroughly prepared, and give serious thought to their goals for sharing the book. There were things to be aware of, groundwork to lay, things to do and not do. Calling into question the entire settler-colonizer mindset... Someone had suggested on Twitter that adults could read the Author Reflection and Historical Note to children first. But it seemed to me that the author's comments alone couldn't fill the gaps in many peoples' (mis)understanding of Indigenous history.

And here's the problem: How many teachers or librarians are able (or willing) to do that much work in order to share a specific picture book? Isn't it more likely to be shared as a sweet story of how people ought to treat each other?

During one conversation, after giving solid attention to my tangled thoughts, Debbie asked, "Would you read it to Jack?" (Jack's my 9-year-old grandson.) My brain started to say, "Mmmaybe, but only if --" But my heart said, "No. No, I wouldn't."

I've applied that question to critiques of many other books -- "What would it feel like to be one or another of my grandkids, reading this?" Why it wasn't with me from the beginning on this one is puzzling.

For non-Native (especially White) adults, there may be some value in personally, privately using counter-narratives like this one, with oneself, to face the chasm between respectful human relationships that sustain life and the real Indigenous history of the continent currently known as North America. But it doesn't feel like a book for children.

Debbie and Jean's thoughts:

We want to see books by Native writers and illustrators succeed. Our commitment to them, however, is superceded by our commitment to children. We'd like to think that a book like this has an audience, but at this point, we're not sure who that would audience would be.

As noted above, we hope that the book brings visibility to Luby and Goade, and we look forward to seeing more from them in the future.

Tuesday, September 24, 2019

Highly Recommended: WE ARE WATER PROTECTORS by Carole Lindstrom and Michaela Goade

Today's post is the twitter thread I did yesterday (September 23, 2019) about We Are Water Protectors, an exquisite book by two Indigenous women: Carole Lindstrom is of Anishinaabe/Métis descent and is tribally enrolled with the Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe. Michaela Goade is of Tlingit descent and is tribally enrolled with the Central Council of the Tlingit and Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska.

WE ARE WATER PROTECTORS, a picture book by Carole Lindstrom & Michaela Goade, is coming out in March 2020https://us.macmillan.com/books/9781250203557 …

WE ARE WATER PROTECTORS is due out March 17, 2010 from Roaring Book Press (Macmillan). I'll have a review of it at American Indians in Children's Literature but for now, I'm over here telling you to pre-order this exquisite book. (us.macmillan.com/books/97812502…)

Those of you who follow Native resistance to exploitation may recall an iconic photo taken in 2013 when Royal Canadian Mounted Police raided a camp of Native people who were there to protect their water from drilling. (newsmaven.io/indiancountryt…)

On the cover of Lindstrom and Goade's book we see the person holding the feather, but behind her... see all the people holding hands? Some are children.

Both, the photo and Goade's art... take my breath away.

Thursday, June 06, 2019

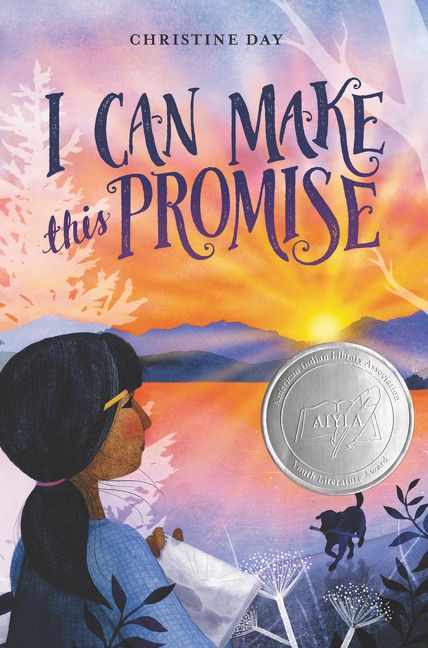

Recommended! I CAN MAKE THIS PROMISE by Christine Day

In her debut middle grade novel—inspired by her family’s history—Christine Day tells the story of a girl who uncovers her family’s secrets—and finds her own Native American identity.

All her life, Edie has known that her mom was adopted by a white couple. So, no matter how curious she might be about her Native American heritage, Edie is sure her family doesn’t have any answers.

Until the day when she and her friends discover a box hidden in the attic—a box full of letters signed “Love, Edith,” and photos of a woman who looks just like her.

Suddenly, Edie has a flurry of new questions about this woman who shares her name. Could she belong to the Native family that Edie never knew about? But if her mom and dad have kept this secret from her all her life, how can she trust them to tell her the truth now?

The cover art by Michaela Goade is stunning!

Day and Goade are Native. The book comes out on October 1st. Order it today!

|

| AICL is pleased to recommend I Can Make This Promise |

Tuesday, February 06, 2018

Recommended: How Devil’s Club Came to Be

“This is an original story by Miranda Rose Kaagweil Worl. Though inspired by ancient oral traditions that have been handed down through the generations, it is not a traditional Tlingit story.”

Often I’m of two minds when authors create original stories based in oral traditions of their cultures. It was a bit disorienting to learn, as a child, that “The Ugly Duckling” and “Princess and the Pea” came from Hans Christian Anderson, and not from old Europe! But original stories that feel old can be engaging and worthwhile in their own right. How Devil’s Club Came to Be, with its uncomplicated plot and Miranda Worl's straightforward prose, has plenty of drama without seeming overwrought. It's easy to read aloud. Here's a sample:

The voice of the Thunderbird clan leader boomed in her head. She spread her arms outward, but they were no longer arms. They were the wings of a giant bird -- they were the wings of a Thunderbird.

|

| Raven tells his niece she must fight the giant. |

I recommend How Devil's Club Came to Be. You can buy it online through Trickster Company or Sealaska Heritage Institute.