Some people read my reviews and think I'm being too picky because I focus on seemingly little or insignificant aspect of a book. The things I pointed out in March were not noted in the starred reviews by the major review journals, but the things I pointed out have incensed people who, apparently, fear that my review will persuade the Caldecott Award Committee that The Secret Project does not merit its award.

In fact, we'll never know if my review is even discussed by the committee. Their deliberations are confidential. The things I point out matter to me, and they should matter to anyone who is committed to accuracy and inclusivity in any children's books--whether they win awards or not.

****

The Secret Project, by Jonah and Jeanette Winter, was published in February of 2017 by Simon and Schuster. It is a picture book about the making of the atomic bomb.

I'm reading and reviewing the book as a Pueblo Indian woman, mother, scholar, and educator who focuses on the ways that Native peoples are depicted in children's and young adult books.

I spent (and spend) a lot of time in Los Alamos and that area. My tribal nation is Nambé which is located about 30 miles from Los Alamos, which is the setting for The Secret Project. My dad worked in Los Alamos. A sister still does. The first library card I got was from Mesa Public Library.

Near Los Alamos is Bandelier National Park. It, Chaco Canyon, and Mesa Verde are well known places. There are many sites like them that are less well known. They're all through the southwest. Some are marked, others are not. For a long time, people who wrote about those places said that the Anasazi people lived there, and that they had mysteriously disappeared. Today, what Pueblo people have known for centuries is accepted by others: present-day Pueblo people are descendants of those who once lived there. We didn't disappear.

What I shared above is what I bring to my reading and review of The Secret Project. Though I'm going to point to several things I see as errors of fact or bias, my greatest concern is the pages about kachina dolls and the depiction of what is now northern New Mexico as a place where "nobody" lived.

"In the beginning"

Here is the first page in The Secret Project:

In the beginning, there was just a peaceful desert mountain landscape,The illustration shows a vast and empty space and suggests that pretty much nothing was there. When I see that sort of thing in a children's book, I notice it because it plays into the idea that this continent was big and had plenty of land and resources--for the taking. In fact, it belonged (and some of it still belongs) to Indigenous peoples and our respective Native Nations.

"In the beginning" works for some people. It doesn't work for me because a lot of children's books depict an emptyness that suggests land that is there for the taking, land that wasn't being used in the ways Europeans, and later, US citizens, would use it.

I used the word "erase" in my first review. That word makes a lot of people angry. It implies a deliberate decision to remove something that was there before. Later in the book, Jonah Winter's text refers to Hopi people who had been making kachina dolls "for centuries." His use of "for centuries" tells me that the Winter's knew that the Hopi people pre-date the ranch in Los Alamos. I could say that maybe they didn't know that Pueblo people pre-date the ranch--right there in Los Alamos--and that's why their "in the beginning" worked for them, but a later illustration in the book shows local people, some who could be Pueblo, passing through the security gate.

Ultimately, what the Winter's they knew when they made that page doesn't really matter, because intent does not matter. We have a book, in hand. The impact of the book on readers--Native or not--is what matters.

Back in March, I did an update to my review about a Walking Tour of Los Alamos that shows an Ancestral Pueblo very near Fuller Lodge. Here's a map showing that, and a photo of that site

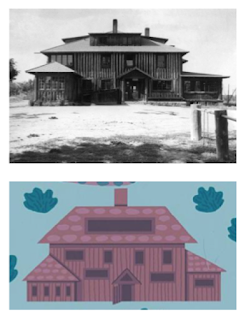

The building in Jeanette Winter's illustration is meant to be the Big House that scientists moved into when they began work at the Los Alamos site of the Manhattan Project. Here's a juxtaposition of an early photograph and her illustration. Clearly, Jeanette Winter did some research.

In her illustration, the Big House is there, all by itself. In reality, the site didn't look like that in 1943. The school itself was started in 1917 (some sources say that boys started arriving in 1918), but by the time the school was taken over by the US government, there were far more buildings than just that one. Here's a list of them, described at The Atomic Heritage Foundation's website:

The Los Alamos Ranch School comprised 54 buildings: 27 houses, dormitories, and living quarters totaling 46,626 sq. ft., and 27 miscellaneous buildings: a public school, an arts & crafts building, a carpentry shop, a small sawmill, barns, garages, sheds, and an ice house totaling 29,560 sq. ft.I don't have a precise date for this photograph (below) from the US Department of Energy's The Manhattan Project website. It was taken after the project began. The scope of the project required additional buildings. You see them in the photo, but the photo also shows two of the buildings that were part of the school: the Big House, and Fuller Lodge (for more photos and information see Fuller Lodge). I did not draw those circles or add that text. That is directly from the site.

Here's the second illustration in the book:

The boys who went to the school in 1945 were not from the people whose families lived in that area. An article in the Santa Fe New Mexican says that:

The students came from well-to-do families across the nation, and many went on to Ivy League colleges and prominent careers. Among them were writer Gore Vidal; former Sears, Roebuck and Co. President Arthur Wood; Hudson Motor Co. founder Roy Chapin; Santa Fe Opera founder John Crosby; and John Shedd Reed, president for nearly two decades of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.

The change from a school to a laboratory

In his review of The Secret Project, Sam Juliano wrote that this take over was "a kind of eminent domain maneuver." It was, and, as Melissa Green said in a comment at Reading While White's discussion of the book,

In her review Debbie Reese observed an elite boy’s school — Los Alamos Ranch School — whose students were “not from the communities of northern New Mexico at that time.” Of course not: local kids wouldn’t have qualified — local kids wouldn’t be “elite”, because they wouldn’t have been white. The very school whose loss is mourned (at least as I can tell from the reviews: I haven’t yet read the book) is a white school built on lands already stolen from the Pueblo people. And the emptiness of the land, otherwise…? It wasn't empty. But even when Natives are there, we white people have a bad habit — often a willful habit — of not seeing them.Green put her finger on something I've been trying to articulate. The loss of the school is mourned. The illustration invites that response, for sure, and I understand that emotion. Green notes that the land belonged to Pueblo people before it became the school and then the lab ("the lab" is shorthand used by people who are from there). There's no mourning for our loss in this book. Honestly: I don't want anyone to mourn. Instead, I want more people to speak about accuracy in the ways that Native people are depicted or left out of children's books.

The Atomic Heritage Organization has a timeline, indicating that people began arriving at Los Alamos in March, 1943. On the next double paged spread of The Secret Project, we see cars of scientists arriving at the site. On the facing page, other workers are brought in, to cook, to clean, and to guard. The workers are definitely from the local population. Some people look at that page and use it to argue that I'm wrong to say that the Winter's erased Pueblo people in those first pages, but the "nobody" framework reappears a few pages later.

By the way, the Manhattan Project Voices site has oral histories you can listen to, like the interview with Lydia Martinez from El Rancho, which is a Spanish community next to San Ildefonso Pueblo.

The next two pages are about the scientists, working, night and day, on the "Gadget." In my review, I am not looking at the science. In his review, Edward Sullivan (I know his name and work from many discussions in children's literature circles) wrote about some problems with the text of The Secret Project. I'm sharing it here, for your convenience:

There was no "real name" for the bomb called the Gadget. "Gadget" was a euphemism for an implosion-type bomb that contained a plutonium core. Like the "Fat Man" bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Gadget was officially a Y-1561 device. The text is inaccurate in suggesting work at Site Y involved experimenting with atoms, uranium, or plutonium. The mission of Site Y was to create a bomb that would deliver either a uranium or plutonium core. The plutonium used in Gadget for the Trinity test was manufactured at a massive secret complex in Hanford, Washington. Uranium, used in the Hiroshima bomb, was manufactured at another massive secret complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. There are other factual errors I'm not going to go into here. Winter's audacious ambition to write a picture book story about the first atomic bomb is laudable but there are too many factual errors and omissions here to make this effort anything other than misleading.

The art of that area...

The text on those pages is:

Outside the laboratory, nobody knows they are there. Outside, there are just peaceful desert mountains and mesas, cacti, coyotes, prairie dogs. Outside the laboratory, in the faraway nearby, artists are painting beautiful paintings.In my initial review, I noted the use of "nobody" on that page. Who does "nobody" refer to? I said then, and now, that a lot of people who lived in that area knew the scientists were there. They may not have been able to speak about what the scientists were doing, but they knew they were there. The Winter's use of the word "nobody" fits with a romantic way of thinking about the southwest. Coyotes howling, cactus, prairie dogs, gorgeous scenery--but people were there, too.

I think the text and illustration on the right are a tribute to Georgia O'Keeffe who lived in Abiquiu. I think Jeanette Winter's illustration is meant to be O'Keeffe, painting Pedernal. That illustration is out of sync, timewise. O'Keeffe painted it in 1941, which is two years prior to when the scientists got started at Los Alamos.

The next double-paged spread is one that prompted a great deal of discussion at the Reading While White review:

The text reads:

Outside the laboratory, in the faraway nearby, Hopi Indians are carving beautiful dolls out of wood as they have done for centuries. Meanwhile, inside the laboratory, the shadowy figures are getting closer to completing their secret invention.In my initial review, I said this:

Hopi? That's over 300 miles away in Arizona. Technically, it could be the "faraway" place the Winter's are talking about, but why go all the way there? San Ildefonso Pueblo is 17 miles away from Los Alamos. Why, I wonder, did the Winter's choose Hopi? I wonder, too, what the take-away is for people who read the word "dolls" on that page? On the next page, one of those dolls is shown hovering over the lodge where scientists are working all night. What will readers make of that?Reaction to that paragraph is a primary reason I've done this second review. I said very little, which left people to fill in gaps.

Some people read my "why did the Winter's choose Hopi" as a suggestion that the Winter's were dissing Pueblo people by using a Hopi man instead of a Pueblo one. That struck me as an odd thing for that person to say, but I realized that I know something that person doesn't know: The Hopi are Pueblo people, too. They happen to be in the state now called Arizona, but they, and we--in the state now called New Mexico, are similar. In fact, one of the languages spoken at Hopi is the same one spoken at Nambé.

Some people thought I was objecting to the use of the word "dolls" because that's not the right word for them. They pointed to various websites that use that word. That struck me as odd, too, but I see that what I said left a gap that they filled in.

When I looked at that page, I wondered if maybe the Winter's had made a trip to Los Alamos and maybe to Bandelier, and had possibly seen an Artist in Residence who happened to be a Hopi man working on kachina dolls. I was--and am--worried that readers would think kachina dolls are toys. And, I wondered what readers would make of that one on the second page, hovering over the lodge.

What I was asking is: do children and adults who read this book have the knowledge they need to know that kachina dolls are not toys? They have spiritual significance. They're used for teaching purposes. And they're given to children in specific ways. We have some in my family--given to us in ways that I will not disclose. As children, we're taught to protect our ways. The voice of elders saying "don't go tell your teachers what we do" is ever-present in my life. This protection is there because Native peoples have endured outsiders--for centuries--entering our spaces and writing about things they see. Without an understanding of what they see, they misinterpret things.

The facing page, the one that shows a kachina hovering over the lodge, is not in full color. It is a ghost-like rendering of the one on the left:

We might say that the Winter's know that there is a spiritual significance to them, but the Winter's use of them is their use. Here's a series of questions. Some could be answered. My asking of them isn't a quest for answers. The questions are meant to ask people to reflect on them.

- Would a Hopi person use a kachina that way?

- Which kachina is that? On that first page, Jeanette Winter shows several different ones, but what does she know about each one?

- What is Jeanette Winter's source? Are those accurate renderings? Or are they her imaginings?

- Why did Jeanette Winter use that one, in that ghost-like form, on that second page? Is it trying to tell them to stop? Is it telling them (or us) that it is watching the men because they're doing a bad thing?

In the long exchange at Reading While White, Sam Juliano said that information about kachina dolls is on Wikipedia and all over the Internet. He obviously thinks information he finds is sufficient, but I disagree. Most of what is on the Internet is by people who are not themselves, Native. We've endured centuries of researchers studying this or that aspect of our lives. They did not know what they were looking at, but wrote about it anyway, from a White perspective. Some of that research led to policies that hurt us. Some of it led to thefts of religious items. Finally, laws were passed to protect us. One is the Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (some good info here), and another is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, passed in 1990. With that as context, I look at that double-paged spread and wonder: how it is going to impact readers?

The two page spread with kachinas looks -- to some people -- like a good couple of pages because they suggest an honoring of Hopi people. However, any "honoring" that lacks substance is just as destructive as derogatory imagery. In fact, that "honoring" sentiment is why this country cannot seem to let go of mascots. People generally understand that derogatory imagery is inappropriate, but cannot seem to understand that romantic imagery is also a problem for the people being depicted, and for the people whose pre-existing views are being affirmed by that romantic image.

Update, Monday Oct 23, 8:00 AM

Conversations going on elsewhere about the kachina dolls insist that Jeanette Winter knows what she is doing, because she has a library of books about kachina dolls, because she's got a collection of them, and because she's had conversations with the people who made them. Unless she says something, we don't know, and in the end, what she knows does not matter. What we have is in the book she produced. In a case like this, it would have been ideal to have some information in the back matter and for some of her sources to have been included in the bibliography. If she talked with someone at the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, it would have been terrific to have a note about that in the back matter, too.

Other conversations suggest that readers would know that kachinas have a religious meaning. Some would, but others do not. Some see them as a craft item that kids can do. There are many how-to pages about making them using items like toilet paper rolls. And, there are pages about what to name the kachina dolls being made. Those pages point to a tremendous lack of understanding and a subsequent trivialization of Native cultures.

Curtains

Tribal nations have protocols for researchers who want to do research. Of relevance here is the information at the website for the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office. There are books about researchers, like Linda Tuhiwai Smith's Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, now in its 2nd edition.

My point: there are resources out there that can help writers, editors, reviewers, teachers, parents and librarians grow in their understandings of all of this.

The Land of Enchantment

The text is:

Sometimes the shadowy figures emerge from the shadows, pale and tired and hallow-eyed, and go to the nearby town.That nearby town is meant to be Santa Fe. See the woman seated on the right, holding a piece of pottery? The style of those two buildings and her presence suggests that they're driving into the plaza. It looks to me like they're on a dirt road. I think the roads into Santa Fe were already paved by then. See the man with the burro? I think that's out of time, too. The Manhattan Project Voices page has a photograph of the 109 E. Palace Avenue from that time period. It was the administrative office where people who were part of the Manhattan Project reported when they arrived in Santa Fe:

You can find other photos like that, too. Having grown up at Nambé, I have an attachment to our homelands. Visitors, past-and-present, have felt its special qualities, too. That’s why so many artists moved there and it is why so many people move there now. I don’t know who first called it “the land of enchantment” but that’s its moniker. Too often, outsiders lose perspective that it is a land where brutal violence took place. What we saw with the development of the bomb is one recent violent moment, but it is preceded by many others. Romanticizing my homeland tends to erase its violent past. The art in The Secret Project gets at the horror of the bomb, but it is marred by the romantic ways that the Winter's depicted Native peoples.

Update, Oct 19, 9:15 AM

Below, in a comment from Sam Juliano, he says that the text of the book does not say that the scientists were going to the plaza in Santa Fe. He is correct. The text does not say that on that page. Here's the next illustration in the book:

That is the plaza. Other than the donkeys, the illustration is accurate. Of course, a donkey could have been there, but it is not likely at that time. If you were on the sidewalk, one of those buildings shown would be the Palace of the Governors. Its "porch" is famous as a place where Native artists sell their work. In the previous illustration, I think Jeanette Winter was depicting one of the artists who sells their work there, at the porch. Here's a present-day photo of Native artists there. (It is, by the way, where I recommend you buy art. Money spent there goes directly to the artist.)

Some concluding thoughts

The Secret Project got starred reviews from Publisher's Weekly, the Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books, The Horn Book, Booklist, and Kirkus. None of the reviews questioned the Native content or omissions. The latter are harder for most people to see, but I am disappointed that they did not spend time (or write about, if they did) on the pages with the kachina dolls.

I fully understand why people like this book. I especially understand that, under the current president, many of us fear a nuclear war. This book touches us in an immediate way, because of that sense of doom. But--we cannot let fear boost this book into winning an award that has problems of accuracy, especially when it is a work of nonfiction.

There are people who think I'm trying to destroy this book. As has been pointed out here and elsewhere, it got starred reviews. My review and my "not recommended" tag is not going to destroy this book.

What I've offered here, back in March, and on the Reading While White page is not going to destroy this book. It has likely made the Winter's uncomfortable or angry. It has certainly made others feel angry.

I do not think the Winter's are racist. I do think, however, that there's things they did not know that they do know now. I know for a fact that they have read what I've written. I know it was upsetting to them. That's ok, though. Learning about our own ignorance is unsettling. I have felt discomfort over my own ignorance, many times. In the end, what I do is try to help people see depictions of Native peoples from what is likely to be their non-Native perspective. I want books to be better than they are, now. And I also know that many writers value what I do.

Now, I'm hitting the upload button (at 8:30 AM on Tuesday, October 17th). I hope it is helpful to anyone who is reading the book or considering buying it. I may have typos in what I've written, or passages that don't make sense. Let me know! And of course, if you've got questions or comments, please let me know.

___________

If you've submitted a comment that includes a link to another site and it didn't work after you submitted the comment, I'll insert them here, alphabetically.

Caldecott Medal Contender: The Secret Project

submitted by Sam Juliano, who asked people to see comments, there, about me (note: tks to Ricky for letting me know I had the incorrect link for Sam Juliano's page. It is correct now.)

Guidelines for Respecting Cultural Knowledge (Assembly of Alaska Native Educators, 2000)

submitted by Melissa Green

Indigenous Intellectual Property (Wikipedia)

submitted by Melissa Green

Intellectual Property Rights (Hopi Cultural Preservation Office)

submitted by Melissa Green

Reviewing While White: The Secret Project

submitted by Melissa Green