I am delighted to see Native-authored books on the SNL stage! That's a big one! I'm adding it to AICL's Milestones page. I know librarians, teachers, and writers are zooming in to see what else is on those shelves. Books matter so much to so many of us. Being represented like this: way cool!

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

- Debbie on Social Media

- 2024 American Indian Literature Award Medal Acceptance Speeches

- Native Removals in 2025 by US Government

Tuesday, January 28, 2025

Angeline Boulley and Eric Gansworth's Books on Saturday Night Live

I am delighted to see Native-authored books on the SNL stage! That's a big one! I'm adding it to AICL's Milestones page. I know librarians, teachers, and writers are zooming in to see what else is on those shelves. Books matter so much to so many of us. Being represented like this: way cool!

Saturday, June 04, 2022

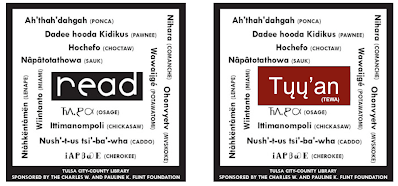

Centering and Featuring Native Languages

In one portion of her remarks, Dawn talked about having a critical lens. That is what AICL is about: bringing a critical lens to the ways that Native peoples, cultures, languages, stories and songs are represented.

For a long time, textbooks and other print media have put non-English words in italics. Setting words apart in that way signals that English is the normal way to speak and write and other languages are “different.” But many people now see this use of italics as a way of “othering” languages and the people who speak them. We are strong advocates for the shift away from italics. You will not see Native words in italics in this book.

Mama usually walks with me, but today my kokum was going to. Kokum is another way to say "grandma" in the Michif language. She moved in with us after my moushoom died last year.

"You like the Beatles?" I said. "We had pretty much all of their albums, but when my brother moved out, he took most of the later ones with him.""We have them all," George said. "My dad's a huge Beatles fan. When we lived in Germany, he took me down to the Reeperbahn in Hamburg, because that's where they got their start. My Mutti about busted a blood vessel.""'Mutti'?""Sorry, German, it's like 'mom.'"

Monday, January 25, 2021

Eric Gansworth (Sˑha-weñ na-saeˀ) -- Member of Eel Clan, Enrolled Onondaga -- Makes History for APPLE (SKIN TO THE CORE)

Today, Eric Gansworth (Sˑha-weñ na-saeˀ), member of the Eel Clan, enrolled Onondaga, born and raised at the Tuscarora Nation won an Honor Award from the American Library Association's Printz Committee for his memoir, Apple (Skin to the Core).

It marks the first time a Native writer was selected to receive distinction in the Printz category. Published by Levine Querido, Gansworth's book is shown here, with the Printz Honor Sticker affixed to the cover:

The Printz Award, first awarded in 2000, is for a book that exemplifies literary excellence in young adult literature. That excellence is seen in the range of presentation Gansworth uses to convey his story. Readers will find poems, prose, photographs, and Gansworth's original art as they read this book.

Apple (Skin to the Core) will resonate with Native people of one Native Nation who, perhaps due to the history of boarding schools, end up on another reservation. Or whose grandmother or great grandmother had a job cleaning the home of a white woman--one legacy of the outing programs at the boarding schools. Or who spends time with family photo albums and sees uncles in things like a Batman costume.

Gansworth's book spans from "the horrible legacy of the government boarding schools, to a boy watching his siblings leave and return and leave again" to "a young man fighting to be an artist who balances multiple worlds." Many will recall being called an apple by tribal members. That slur (red on the outside, white on the inside) is meant to sting, but Gansworth has a different perspective on it that I like quite a lot.

Searing and poignant, humorous and endearing, it is clear why Apple (Skin to the Core) was selected for an Honor by the Printz Committee.

Thursday, October 08, 2020

Highly Recommended: APPLE (SKIN TO THE CORE) by Eric Gansworth

Monday, October 12 is Indigenous Peoples' Day. There will be many virtual events taking place. Top of my list is the one from Arizona State University. Eric Gansworth will open their day of events. When you click on through to register for his lecture (at noon, Central Time) you will see that Gansworth was selected to deliver the 2020 lecture in the prestigious Simon Ortiz Red Ink Indigenous Speaker Series. People in Native studies or who study the writing and scholarship of Native people will recognize names of people who have given that lecture. In the field, being selected to give that lecture has tremendous significance. Videos for most of the talks are available at the site. If you are new to your work in learning about Native writing, make time to watch and study all of them!

Gansworth will be talking about his new book, Apple (Skin to the Core). Across the hundreds of Native Nations, our life experiences differ. Census information has shown that about half of us grow up in suburban or urban areas. I'm glad to see books set in those spaces.

Some of us grew up on our homelands or on reservations. Native-authored books for children and young adults that reflect a reservation sense-of-place with the integrity that Gansworth brings to his writing, are rare. On Indigenous Peoples Day, I'll be giving a talk, too. My audience will be Pueblo peoples. I expect a large segment of the audience to be people who are living on their Pueblo homelands. And so, I'm emphasizing books like Apple (Skin to the Core) that will speak directly to a reservation-based experience. Of course, everyone should read it and Gansworth's other two books, If I Ever Get Out of Here and Give Me Some Truth.

As I read through his memoir, I linger over some of what I read... I want to tell you about this poem, or what I see on that page, but that's not the thrust of this post. A review is forthcoming. Today, I celebrate the gifts that Eric Gansworth gives to us, in every word he writes, in each poem, story, and book.

Eric Gansworth (Sˑha-weñ na-saeˀ), a writer and visual artist, is an enrolled member of the Onondaga Nation. He was raised at the Tuscarora Nation, near Niagara Falls, New York. Currently, he is a Professor of English and Lowery Writer-in-Residence at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York.

Friday, January 04, 2019

Highly Recommended! "Don't Pass Me By" by Eric Gansworth, in FRESH INK (edited by Lamar Giles)

The story is titled "Don't Pass Me By." Four words, packed with meaning. They're never used in the story itself, but they are very much a part of what we read in the story.

Don't pass me by, Doobie could say to Hayley. They are Native kids in the 7th grade. They're from the same reservation but Hayley's dad is white and she can pass for white. Doobie can't. He's the target of harassment that she doesn't get. She can--and does--walk right by Doobie. Though they know each other, she doesn't acknowledge him until they're on the bus back to the reservation.

Don't pass me by, Doobie pretty much says to Mr. Corker. He's the Health teacher. For this particular lesson, the boys stay with Mr. Corker and the girls go with Ms. D'Amore. The lesson? Parts of the body. The activity? Label the body parts on the first worksheet. For the second worksheet, Mr. Corker hands out two boxes of colored pencils. One box is flesh; the other is burnt sienna. He expects the boys to color the boy on the worksheet with the flesh pencil, and to use the burnt sienna pencil to draw underarm and pubic hair. Other Native boys in the class do as expected, but Doobie uses the burnt sienna pencil for the body and his regular pencil for the hair. He's added a long black sneh-wheh, like his own. When class is over he turns in his worksheet after everyone else has left. Mr. Corker looks at it and says (p. 52):

"I see. Hubert. But you know, the assignment wasn't a self-portrait."

"It was," if you're white," I said.And, he continues (p. 52):

"Your pencils only allowed for one kind of boy," I said.As he's telling Mr. Corker all this, he thinks about older siblings and cousins who didn't make trouble with assignments like this. His stomach is in knots as he talks with Mr. Corker. He begins to understand why those siblings and cousins chose

"...to be silent, to think of yourself as a vanished Indian. Everywhere you looked, you weren't there."Native kids are in that position every day in school... asked to complete assignments that don't look like them, by teachers who don't see them... Who refuse to see the whiteness that is everywhere.

See why this story makes my heart ache? Gansworth's story is one that will tell Native kids like Doobie that they are not alone. And it has a strong message for teachers, too: Don't be Mr. Corker.

And if you're not a Mr. Corker, I'm pretty sure you know plenty of teachers who are... and you can interrupt that. You can be like Doobie.

Get several copies of Fresh Ink. I reviewed Gansworth's story, but its got twelve others from terrific writers: Schuyler Bailar, Melissa de la Cruz, Sara Farizan, Sharon G. Flake, Malinda Lo, Walter Dean Myers, Daniel José Older, Thien Pham, Jason Reynolds, Aminah Mae Safi, Gene Luen Yang, and Nicola Yoon. I highly recommend it. Published in 2018 by Random House, it is one you'll come back to again and again.

Friday, May 25, 2018

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: Eric Gansworth's GIVE ME SOME TRUTH

There were moments when I thought "Don't do that, Maggi!" and others were I cheered for what she was doing.

What I share today are specific passages from the first two chapters of the book and why I like them. Let's start with a description of the book:

Carson Mastick is entering his senior year of high school and desperate to make his mark, on the reservation and off. A rock band -- and winning Battle of the Bands -- is his best shot. But things keep getting in the way. Small matters like the lack of an actual band, or his brother getting shot by the racist owner of a local restaurant.

Maggi Bokoni has just moved back to the reservation with her family. She's dying to stop making the same traditional artwork her family sells to tourists (conceptual stuff is cooler), stop feeling out of place in her new (old) home, and stop being treated like a child. She might like to fall in love for the first time too.

Carson and Maggi -- along with their friend Lewis -- will navigate loud protests, even louder music, and first love in this stirring novel about coming together in a world defined by difference.

Now, my thoughts!

In chapter one, we're inside Carson's house on Memorial Day weekend, 1980. His brother, Derek, comes into Carson's room. He's got a bullet wound in his rear end. Carson helps him stop the bleeding. They're doing this as quietly as they can because they don't want their parents to know about it. In the description, you read that Derek got shot by the racist owner of a local restaurant. We learn about how that happened, later in the book.

A passage in chapter one that I like a lot is when Carson tells us that Derek had "hit the jackpot in the Indian Genes roll of the dice" (p. 4). You wondering what that means? When Derek came into Carson's bedroom, Carson noticed he was not looking so good and tells him "You look kind of, um, pale." What Gansworth is getting at, there, is the range of what Native people can look like--even within the same family. Most people in the world think that we all have straight black hair, and dark skin, and high cheekbones... You know what I mean, right? If you don't, take a stroll down the aisle of the romance novels next time you're in the bookstore. Or, pull up a book seller website. Look for the ones about about Native men, you'll see what I mean. The fact: that image is a stereotype -- and it is something that Carson is dealing with.

In chapter two, we meet Maggi! The book description tells us that she has just moved back to the reservation, but that happens at the end of the chapter. Chapter two opens with Maggi and her sister, Marie, who are sitting at a table at Niagara Falls, selling handmade Indian souvenirs they've made. We learn that Maggi likes to do beadwork that isn't traditional. And that she likes to sing and use a water drum. And that it is helpful to their sales if she'd sing and drum, because it attracted tourists. These two girls know how to play to the White guilt of the tourist crowd in other ways, too. I think what they do is hilarious!

Packed in that chapter, though, are some of those truths I was talking about earlier. A certain kind of beadwork is much-loved on the reservation. Now--I imagine some of you read "beadwork" and thought about beaded headbands--but Maggi is thinking about things that tell readers that Native people today... are of this day. We wear baseball caps, but sometimes, those caps are beaded. And because I'm writing this post in the midst of graduation celebrations, I'm seeing a lot of friends and colleagues sharing photos of mortarboards that are beaded (do a search using beaded baseball cap, or beaded mortarboard and you'll see what I mean).

We get another truth on page 17, as Maggi thinks about the permit they have to sell their work, and how it is "keeping the Porter Agreement alive, though the State Parks official vendors have tried for years to break the treaty)." That right there is definitely something that some Native readers will know about, and that the rest of us have to look up. It is history that isn't taught in textbooks--but that is known by those that it directly impacts. I'm really glad to see it and hope that people will look it up. Citizens of the US don't know much about Native history--but it matters a lot in ways they ought to know!

Another part in chapter two that made me laugh was Maggi imagining a painting or beadwork she might do--in the conceptual style that Andy Warhol did... but she'd do "rows of Commodity Food cans, maybe ones we liked ("Peaches") and one we hated ("Meat"), with their basic pictures on the can in case you didn't know how to read" (p. 17). Native people who grew up during that time and got "commods" know exactly what those cans look like.

As the chapter closes, Maggi's mom tells them they're moving back to the reservation, and we shift back to Carson. I might be back with more thoughts, but for now, I'll point you to Traci Sorell's interview of Gansworth, over at Cynsations. And I'll recommend that you get a copy of Give Me Some Truth. It comes out on May 29. I've read the ARC I got some weeks back, and have an e-book copy on order. And--if you're going to ALA in New Orleans, get a signed copy! Gansworth will be there.

Published in 2018 by Arthur A. Levine (Scholastic), I am pleased as can be to say that I highly recommend Give Me Some Truth!

Wednesday, November 01, 2017

Debbie--have you seen Eric Gansworth's GIVE ME SOME TRUTH?

Here's the synopsis:

Carson Mastick is entering his senior year of high school and desperate to make his mark, on the reservation and off. A rock band -- and winning the local Battle of the Bands, with its first prize of a trip to New York City -- is his best shot. But things keep getting in the way. Small matters like the lack of an actual band, or the fact that his brother just got shot confronting the racist owner of a local restaurant.

Maggi Bokoni has just moved back to the reservation from the city with her family. She's dying to stop making the same traditional artwork her family sells to tourists (conceptual stuff is cooler), stop feeling out of place in her new (old) home, and stop being treated like a child. She might like to fall in love for the first time too.

Carson and Maggi -- along with their friend Lewis -- will navigate loud protests, even louder music, and first love in this stirring novel about coming together in a world defined by difference.

I recommended Gansworth's If I Ever Get Out of Here a few years ago. Still do! Every talk I give features that book.

I'll be back with a review of Give Me Some Truth, later, but wanted to take a minute, today, to say that I highly recommend it! Pre-order a copy. The hardcover will be available on May 29, 2018.

Wednesday, September 27, 2017

The Cover for Eric Gansworth's GIVE ME SOME TRUTH

Today, Nerdy Book Club was the host for the cover reveal for his next book, Give Me Some Truth, which will be out in 2018.

Here's some of what he said:

[W]hen I’m getting ready to write a new novel, I look at my existing cast of characters, and develop a new one by first identifying which other characters they’re related to. I ask the new character, “Now whose kid are you?”

As a Native person, I smiled as I read "whose kid are you" and I wondered who would be at the center of Give Me Some Truth! Who, I wondered, would take me back into a Native community that feels very real to me.

Gansworth doesn't have to sit there at his computer and think "how would a Native kid" think or feel or speak. He's writing from a lived experience. His writing resonates with me and so many Native people who have read and shared If I Ever Get Out of Here.

Head over to Nerdy Book Club and see what else Gansworth said, and keep an eye out for Give Me Some Truth.

_______________________

Back to add Gansworth's bio:

Eric Gansworth (Sˑha-weñ na-saeˀ) is Lowery Writer-in-Residence and Professor of English at Canisius College in Buffalo, NY and was recently NEH Distinguished Visiting Professor at Colgate University. An enrolled member of the Onondaga Nation, Eric grew up on the Tuscarora Indian Nation, just outside Niagara Falls, NY. His debut novel for young readers, If I Ever Get Out of Here, was a YALSA Best Fiction for Young Adults pick and an American Indian Library Association Young Adult Honor selection, and he is the author of numerous acclaimed books for adults. Eric is also a visual artist, generally incorporating paintings as integral elements into his written work. His work has been widely shown and anthologized and has appeared in IROQUOIS ART: POWER AND HISTORY, THE KENYON REVIEW, and SHENANDOAH, among other places, and he was recently selected for inclusion in LIT CITY, a Just Buffalo Literary Center public arts project celebrating Buffalo’s literary legacy. Please visit his website at www.ericgansworth.com.

Tuesday, November 10, 2015

Photo: Debbie Reese and Eric Gansworth at AWP2015

AWP is the Association of Writers and Writing Programs. Here's the blurb about their conference (from their website):

The AWP Conference & Bookfair is an essential annual destination for writers, teachers, students, editors, and publishers. Each year more than 12,000 attendees join our community for four days of insightful dialogue, networking, and unrivaled access to the organizations and opinion-makers that matter most in contemporary literature. The 2015 conference featured over 2,000 presenters and 550 readings, panels, and craft lectures. The bookfair hosted over 800 presses, journals, and literary organizations from around the world. AWP’s is now the largest literary conference in North America.AWP 2015 was the first time I went to that conference. I was there as a moderator for a panel that included Eric and Debby Dahl Edwardson, too. Good times there, and with Sarah Park Dahlen and her family, too!

Monday, April 28, 2014

We Need Diverse Books that aren't "Blindingly White"

If you're not a white male--or a cat--you're out of luck. Rachel Renee Russell, author of the Dork Diaries (which I haven't read), was offered a set of pre-written questions with which to use to interview what Rick Riordan (one of the panelists) called the "Four White Dudes of Kids' Lit" (see his tweet on April 11, 2014). Russell asked to be a panelist instead, and that apparently went nowhere.

If you've been following this situation, you've likely read some of the responses to it. Over the weekend, a new response emerged that involves ACTION. Here's the poster for the We Need Diverse Books event taking place this week:

Perusing the 15 books in that set, it is clear that the planners of the campaign envision diversity in a broad range. It isn't, in other words, just books by or about authors of color, or authors who are citizens or members of one of the 500+ federally recognized tribes. It is about body type. It is about sexual orientation. It is about all of us.

What can you do?

RIGHT NOW (or sometime before May 1), take a photograph that in some way states why you think we need books that represent all of us. The photo can capture whatever it is you want to highlight. The planners suggest holding a sign that says "We need diverse books because _____." Send your photo to weneeddiversebooks@yahoo.com or submit it via the Tumblr page. Starting at 1:00 PM EST on May 1, 2014 people will be using the hashtag #WeNeedDiverseBooks to share the photos.

On May 2, 2014 there will be a Twitter chat--again using that hashtag--at 2:00 PM EST. Share your thoughts on existing problems with the lack of diversity in children's and young adult literature, and share the positives, too.

On May 3, 2014 at 2:00 EST there will be book giveaways and a "put your money where your mouth is" component to the campaign.

Regular readers of American Indians in Children's Literature know that I encourage people to buy books from independent booksellers. My recommendation? Birchbark Books.

The poster (above) includes Eric Gansworth's If I Ever Get Out of Here, which you can get from Birchbark Books. I want you to get it, but I also want you to get every book on my lists of recommended books. You can start with the lists I put together for the 2008 and 2013 "Focus On" columns I wrote for School Library Journal. Here's the lists:

Native Voices (November 1, 2008)

Resources and Kid Lit about American Indians (November 5, 2013)

Please join the campaign!

Update: Monday April 28 2014, 3: 15 PM

A good sign: BookCon making some changes! Rachel Renee Russell was offered a position on the KidLit panel:

Tuesday, January 28, 2014

Gansworth's IF I EVER GET OUT OF HERE on 2014 Best Fiction for Young Adults list

Eric Gansworth's If I Ever Get Out of Here is on the list! Congratulations, Eric!

Saturday, November 02, 2013

Presidential Proclamation: National Native American Heritage Month, 2013

So---how can you (parent, teacher, librarian) turn President Obama's proclamation into a here-and-now activity that can use anytime of the year?

In the first paragraph, President Obama says "When the Framers gathered to write the United States Constitution, they drew inspiration from the Iroquois Confederacy..." Do you know what he means by that? Take a look at House Concurrent Resolution 331, passed in October 1988. For information about one of the Native nations that comprise the Iroquois Confederacy, visit the website of the Onondaga Nation. If you work with middle school students, get copies of Eric Gansworth's If I Ever Get Out of Here. He's Onondaga, and his novel is outstanding.

In the second paragraph, President Obama says "we must not ignore the painful history Native Americans have endured..." You probably know about wars between the U.S. and American Indian nations, but did you know universities had research studies in which they sterilized Native people?

In the third paragraph, President Obama says "In March, I signed the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act, which recognizes tribal courts' power to convict and sentence certain perpetuators of domestic violence, regardless of whether they are Indian or non-Indian." To read about that, pick up a copy of Louise Erdrich's The Round House.

In the fourth paragraph, President Obama invites Americans to "shape a future worthy of a bright new generation, and together, let us ensure this country's promise is fully realized for every Native American." Most books about American Indians are inaccurate and biased. As such, they shape ignorance in non-Native people. Let's set those ones aside and work towards that bright new future for all of us.

Saturday, June 01, 2013

American Indians in Children's Literature's "Show Me The Awesome" post

|

| Design by John LeMasney via lemasney.com |

I began my post on Thursday (May 30), but storms that made their way across the nation interrupted me by messing with my electricity and the trees in my back yard, too. So, I'm loading my contribution to Show Me The Awesome today (June 1, 2013)

The storms, in their own way, mark what I try to do with American Indians in Children's Literature, and with my lectures and publications. Storms uproot trees. They change the landscape.

In significant ways, the landscape of children's literature changes organically, as society changes. There are exceptions, of course, and that's what is at the heart of my work.

I've been working in children's literature since the early 1990s. I started publishing American Indians in Children's Literature (AICL) in 2006. It has steadily garnered a reputation as the place that teachers and librarians can go for help in learning how to discern the good from the bad in the ways that American Indians are portrayed in children's books. People who sit on award committees and major authors, too, write to me. So do editors at the children's literature review journals, and, editors at major publishing houses.

Right now, I'm very proud to have played a role in getting a certain book published. That book is Eric Gansworth's If I Ever Get Out of Here. Its publisher is Scholastic, and its editor is Cheryl Klein. It is due out in a few weeks. In it, you'll read this in the acknowledgements:

Nyah-wheh to Debbie Reese (Nambe Pueblo) and her essential work at American Indians in Children's Literature for her courage, kindness, activism, and generosity, and for introducing me to my editor at Arthur A. Levine. Thank you to Cheryl Klein, that very editor, for actively seeking out indigenous writers, and investing in my work over the long haul.The introduction took place over email a few years ago. Once it was made, I was out of the picture. I wondered, though, if the introduction would bear fruit. And when I learned a book was in the works, I wondered what it was about. Would I like it? Would I be able to recommend it? Now, I know. With Eric's book in my hands, I can Show YOU The Awesome.

My essay about why it is awesome is here: What I Like about Eric Gansworth's IF I EVER GET OUT OF HERE.

Years ago, illustrator James Ransome was asked (at a conference at the Cooperative Center for Children's Books at the University of Wisconsin) why he hadn't illustrated any books about American Indians. He replied that he 'hadn't held their babies." I've written about his remark several times because it beautifully captures so much.

Lot of people write about (or illustrate) American Indians without having held our babies. They end up giving us the superficial or the artificial. They mean well, but, we don't need superficial or artificial, either. We need the awesomes. Yeah--I know--'awesomes' isn't a legitimate word, but I'm using it anyway. We have some awesomes. I've written about them on AICL, but we need more awesomes. Lots more, so that we can change the landscape.

Order Eric's book, and those I mark as 'Recommended' on AICL. You could also check out the short lists (by grade level) at the top of the right-hand column of AICL. Join me. Let's change the landscape together.

Wednesday, May 29, 2013

What I Like about Eric Gansworth's IF I EVER GET OUT OF HERE

-----------------------------------------------------------

Update: 12:20 PM, Wednesday, May 29, 2013

Praise for Gansworth's novel:

On the cover of the ARC (advanced reader copy), Francisco X. Stork says: "The beauty of this novel lies in the powerful friendship between two young men who are so externally different and so internally similar. Wonderful, inspiring, and real."

Online, Cynthia Leitich Smith writes that it is a "heart-healing, moccasins-on-the-ground story of music, family and friendship."

Sunday, May 26, 2013

Books by Native Authors at Bus Boys and Poets

As I browsed the Children's book section, I saw several books I adore on their shelves. I took photos of them.

Tim Tingle's Crossing Bok Chitto and Saltypie are in the picture books section. So is Cynthia Leitich Smith's Jingle Dancer but my photo of it was far too blurry to use here. On the shelves with books for older children, I spotted Louise Erdrich's The Game of Silence and Chickadee, and Smith's Indian Shoes. And on the shelf where the board books are, is Richard Van Camp's Little You. Here's my cropped snapshots of them:

I gotta say---I was tickled as can be to see all these books! In one place! And there were others, too. Many others. They were featuring Diverse Energies, which includes a story by Cherokee author, Daniel H. Wilson:

If you're in Washington D.C., put a trip to Busboys and Poets on your list of places to go. While there, buy some books and have something to eat. If you can't get there, visit the website and... buy some books that way.

Very soon, they'll have Eric Gansworth's If I Ever Get Out of Here, too.

Course, I focused on books by Native authors, but they've got a wide range of books by a wide range of authors whose books fit the theme of social justice. Stop by! Check out their website! Support independent bookstores! And always--support social justice.