When I started grad school in the 1990s, I remember reading that children's books can fill the huge gaps in what textbooks offer.

I doubt, for example, that there's a single textbook out there that teaches kids about the termination programs of the 1950s.

Indeed, most non-Native people reading this review of Indian No More probably don't know what the termination program was!

Those who do know what I'm talking about likely didn't learn it in school. They learned about it because their family--like Charlene Willing McManus's--was caught in a government program that determined they were no longer Native.

****

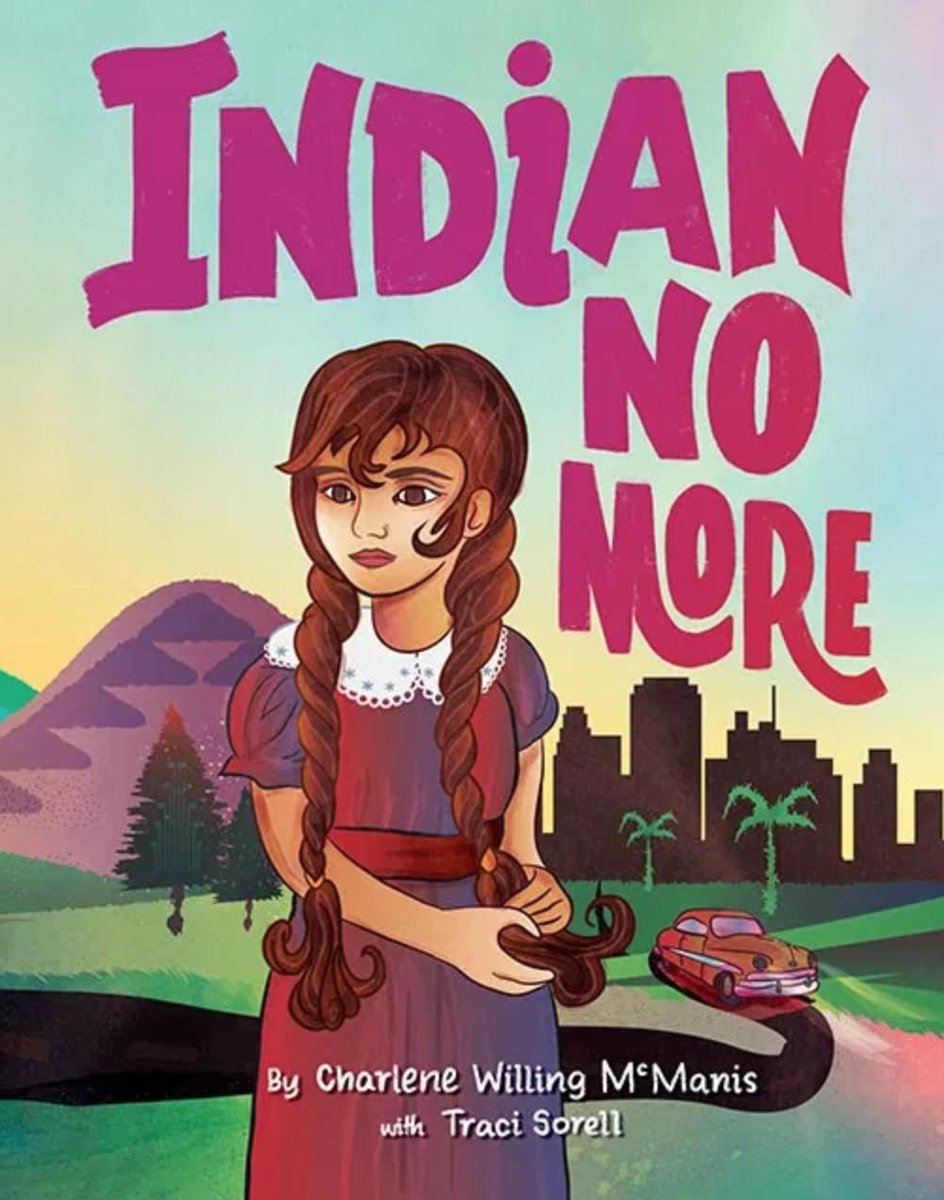

Here's the book description for Indian No More:

Regina Petit's family has always been Umpqua, and living on the Grand Ronde reservation is all ten-year-old Regina has ever known. Her biggest worry is that Sasquatch may actually exist out in the forest. But when the federal government signs a bill into law that says Regina's tribe no longer exists, Regina becomes "Indian no more" overnight--even though she was given a number by the Bureau of Indian Affairs that counted her as Indian, even though she lives with her tribe and practices tribal customs, and even though her ancestors were Indian for countless generations.

With no good jobs available in Oregon, Regina's father signs the family up for the Indian Relocation program and moves them to Los Angeles. Regina finds a whole new world in her neighborhood on 58th Place. She's never met kids of other races, and they've never met a real Indian. For the first time in her life, Regina comes face to face with the viciousness of racism, personally and toward her new friends.

Meanwhile, her father believes that if he works hard, their family will be treated just like white Americans. But it's not that easy. It's 1957 during the Civil Rights Era. The family struggles without their tribal community and land. At least Regina has her grandmother, Chich, and her stories. At least they are all together.

In this moving middle-grade novel drawing upon Umpqua author Charlene Willing McManis's own tribal history, Regina must find out: Who is Regina Petit? Is she Indian? Is she American? And will she and her family ever be okay?

That last paragraph is important. It tells us that the author drew on her own tribal history in writing the story. In the Author's Note, McManis tells us a lot more. She was a baby when the US Congress decided that her tribal nation, the Umpqua, was no longer a Native Nation that would have a government-to-government relationship with the US government. Her family moved to Los Angeles and experienced much of what you read in the story.

Rather than provide an in-depth review of Indian No More, I'm asking that you go read the review written by Ashleigh, a thirteen-year-old who is part of the @OfGlades teens (on Twitter) that blog at Indigo's Bookshelf.

Each time they write a review, I tell friends and colleagues to go read what the intended audience thinks about the book. By that, I mean young readers, but it is also vitally important that people know what Native teens think about books written for people their age!

I read Indian No More in June and started a Twitter thread on it, on June 28. I'm sharing that thread below.

Four Native women worked to bring this book--this exquisite story--to readers. I highly recommend it.

Each time they write a review, I tell friends and colleagues to go read what the intended audience thinks about the book. By that, I mean young readers, but it is also vitally important that people know what Native teens think about books written for people their age!

****

I read Indian No More in June and started a Twitter thread on it, on June 28. I'm sharing that thread below.

I've never read a book like INDIAN NO MORE. Written by Charlene Willing McManis, the book cover also has "with Traci Sorell" on it:

It stands apart from anything I've read before because it is about the US government's termination of the Grand Ronde Tribe, and others, too. The US government literally decided that members of these tribes were no longer Indians (hence the bk title).

On the Grand Ronde Tribe's website, there's information about what happened. I always tell teachers that a tribal nations website is a primary source.

There are several tribal nations on the Grand Ronde Reservation. In education, we often talk about "best practice." When talking about Native Nations and people, it is best practice to name the specific one being discussed. With Indian No More, best practice means teachers and librarians should specify the tribal nation the story is about: Umpqua.

As far as I know, Indian No More is the first book for children that is about the life of a child and her family when their tribe was terminated and then, relocated.

The story in Indian No More is one reason why it is unique. Another is the team that brought it forth. I'm looking at the back matter. The Author's Note from Charlene appears, first, followed by a Co-Author's Note from Traci that tells us why her name is also on the book.

Charlene got cancer. She asked Traci to revise and polish what she'd written. In her note, Traci talks about being asked to do that. She says she was honored, which is to be expected but she tells us so much more!

One of the questions she had was how she--a citizen of the Cherokee Nation--could step in to do a book about an entirely different tribal nation. I've never seen anyone's reflections on doing that, before.

In Traci's words are a deep respect for Charlene, her story, her nation. This is so important!

I'm flailing as I try to come up with words that capture why Traci's thoughts are so different from the words of white writers who tell us they're writing a story because Native kids/adults they taught asked them to do it. Their words smack of saviorism.

The respect I read in Traci's words are also in the next item in the back matter: a note from the editor, Elise McMullen-Ciotti.

I'm a fierce advocate for back matter. The words of these three women, plus the photographs in Charlene's note... like I said, I'm flailing for words.

I'm a fierce advocate for back matter. The words of these three women, plus the photographs in Charlene's note... like I said, I'm flailing for words.

My review of INDIAN NO MORE will be up soon at American Indians in Children's Literature. Before I go I have one more thing to say. The cover art is by Marlena Myles. She's Native, too.

Four Native women worked to bring this book--this exquisite story--to readers. I highly recommend it.