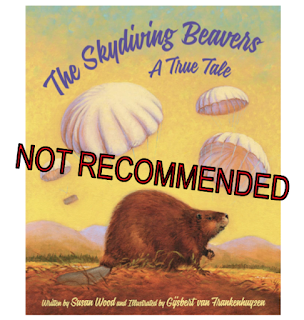

The Skydiving Beavers: A True Tale

Written by Susan Wood

Illustrated by Gijsbert van Frankenhuyzen

Published by Sleeping Bear Press

Published in 2017

Reviewed by Debbie Reese

Review Status: NOT RECOMMENDED

A couple of readers have written to ask me about The Skydiving Beavers: A True Tale. Written by Susan Wood and illustrated by Gijsbert van Frankenhuyzen, it--and reviews of it--are disappointing.

Here's the description:

Just after World War II, the people of McCall, Idaho, found themselves with a problem on their hands. McCall was a lovely resort community in Idaho's backcountry with mountain views, a sparkling lake, and plenty of forests. People rushed to build roads and homes there to enjoy the year-round outdoor activities. It was a beautiful place to live. And not just for humans. For centuries, beavers had made the region their home. But what's good for beavers is not necessarily good for humans, and vice versa. So in a unique conservation effort, in 1948 a team from the Idaho Fish and Game Department decided to relocate the McCall beaver colony. In a daring experiment, the team airdropped seventy-six live beavers to a new location. One beaver, playfully named Geronimo, endured countless practice drops, seeming to enjoy the skydives, and led the way as all the beavers parachuted into their new home. Readers and nature enthusiasts of all ages will enjoy this true story of ingenuity and determination.

AICL readers and those who are learning to read critically will spot the problems in the description right away. It can be difficult to see what is not there on the page, but it is important to ask--right away--what people is the author talking about? She says "the people of McCall, Idaho" who are trying to build homes on a lake. The author doesn't say white people but that's who they're talking about. These white people have a problem with beavers that had "for centuries" been making that area their home. True enough, beavers had been there for centuries, but who else was there, before? The author has erased Nez Perce peoples from what was their homeland.

You may have noted that the subtitle to the book is "A True Tale." Wood is, in short, telling you some facts about something that actually happened. She leaves out Nez Perce people, and in her telling of this story, she talks about the beavers in ways that I find deeply troubling. They had built their homes there, first, but then the white people "muscle in" to the area. The beavers didn't like that, and so, they gnaw on trees and "trash" the peoples views of the forest. Wood writes that it was "A real turf war. It seemed McCall just wasn't big enough for everybody."

The beaver are in the way.

They have to be removed.

The Idaho Fish and Game department considers ways to do that: round them up, put them in cages. The ways they consider are precisely the ones used to remove Indigenous peoples from their homelands when white people wanted those lands. In the end they decide to move them by way of airdrop. That stopped me cold. I don't think it is clever, at all.

The person who came up with that plan is a man named Elmo Heter. He came up with a design and to make sure it would work, he tested it several times using a beaver they named Geronimo. Why that name?! Heter doesn't tell us why, in his article about the project.

In the fourth paragraph of her author's note, Wood tells us that "Elmo's beaver relocation by parachute was an inventive idea in 1948, it likely wouldn't happen today" because now, scientists know that beavers are good for the environment. Programs to move beavers don't take place anymore, but, Wood says "it's still fun to think that the descendents of daredevil Geronimo and his fellow skydiving rodents are likely alive, well, and happily gnawing deep in the wilds of Idaho."

Why, I wonder did this book get published? Because it is a "fun" story about something that happened to beavers? I think it was cruel. Heter, in the 1940s and now, Wood in the 2010s seem not to care about that. And in reading this story aloud to children, are people affirming that cruelty without realizing it? I think so.

I do not recommend The Skydiving Beavers: A True Tale. Some true stories ought not be provided to children as entertainment.