Before you read Tim Tingle's

Saltypie to your child or students in your classroom or library, spend some time studying what Tingle says at the end of the book, on the pages titled "How Much Can We Tell Them?"

There, you'll learn a little about Tim's childhood, and some about his father, grandmother, the

Choctaw Nation, and, the rock-throwing incident in the book. Here's an excerpt:

I always knew we were Choctaws, but as a child I never understood that we were Indians. The movies and books about Indians showed Indians on horseback. My family drove cars and pickup trucks. Movie Indians lived in teepees. We lived in modern houses. Indians in books and on television hunted with bows and arrows. My father and my uncles hunted, too, with shotguns, but mostly they fished.

I have similar memories of my own. I watched the Indians on television and thought they weren't really Indians. I knew that we were Pueblo Indians, but we didn't look or live anything at all like the ones on TV, so I figured they weren't real. Tingle's note has a lot of very powerful information in it:

We know our history never included teepees or buffaloes. We were people of the woods and swamps of what is now called Mississippi. Early Choctaws had gardens and farms. For hundreds of years, they lived in wooden houses.

and

Long before explorers arrived from Europe, we had a government, a Choctaw national government. We selected local and national leaders. We recognized women as equal citizens.

Did you do a double take as you read his words? I bet your students will! Indian people---prior to Europeans arrival on the continent that came to be known as North America---had governments?! Women were equal citizens?!!

Those are powerful and important words for you (the adult) to carry with you every single time you pick up a book that has American Indians in it. We weren't primitive. We weren't savage.

Tingle's note goes on to talk about things the Choctaw people experienced, such as the Trail of Tears, boarding school and racism. And, he talks about stereotypes in children's books, and he suggests that teachers can use

Saltypie to dispel some of those stereotypes.

Turning now, to the book itself. In it are several stories.

The first double-paged spread of the book shows a young boy with bees around him. He's wearing a bright green button-down shirt with the sleeves rolled up. That boy is Tim, and the stories in the book are from his life.

First up is getting stung by a bee. His opening sentences capture the reader right away:

A bee sting on the bottom! Who could ever forget a bee sting on the bottom?

No doubt, those lines will elicit both laughs and groans from children--especially those who know the throbbing pain of a bee sting! Obviously in distress, Tim runs to an arbor where his grandmother, who he calls Mawmaw, comforts him, but teaches him, too, when she asks "Didn't you hear the bees?" and says the bee sting was "some kind of saltypie."

From there, Tingle takes his readers back to his grandmother's early years as a mother, and tells us about the word "saltypie."

The year was 1915, and Tim's grandparents (and Tim's dad, who was then two years old), moved to Texas. On that first morning his grandmother stepped outside her new home, and was struck in the face by a stone, thrown, Tingle writes, by a boy. Covering her face with her hands, blood seeped between her fingers. Not knowing it was blood, Tim's father (then a toddler), thought it was cherry pie filling. He reached up, got some on his fingertip, and tasted it. Course, it wasn't the sweet taste he expected, and he uttered "Saltypie!" and spit it out. His mother hugged him. Though she was crying and shaken by the incident, she saw humor in her son's unmet expectation of something sweet, and laughed as she held him.

Moving forward in time to 1954, Tim is six years old, and he and his dad are visiting Mawmaw and Pawpaw, who still live in that house they moved to in 1915. Tim asks if he, like the adults gathered around the table, can have a cup of coffee. He watches as Mawmaw pours coffee, and sees that she puts her thumb into each cup before she fills it. He doesn't want her thumb in his cup, and covers it with his hand. Pawpaw and Tim's aunt are surprised by his action, and his aunt takes him outside for a moment, where he learns that Mawmaw is blind.

In a family gathering that night, Tim learns a lot about his grandmother's life. From his uncle, he learns about the stone that was thrown at her, and that people back then didn't like Indians. When he asks his uncle "What is saltypie?" his uncle says

"It's a way of dealing with trouble, son. Sometimes you don't know where the trouble comes from. You just kinda shrug it off, say saltypie. It helps you carry on."

The next story Tingle relates is set in 1970, when his grandmother is hospitalized for an eye transplant through which they hope she will regain her sight. His extended family is gathered round, waiting, telling stories to pass the time. By then, Tingle is a college student.

One of the stories Tim told is about his grandmother's years at Tuskahoma Academy, a boarding school for American Indian girls. The color palette on the page for that story is, appropriately, a somber blue. There, Mawmaw as a young child, stands, looking wistful, stuck at the school at Christmas time. That illustration is exceedingly powerful. Actually, it is only one of many illustrations in the book that are astounding in what they convey.

The illustrator for the book is Karen Clarkson. Like Tingle, she is enrolled with the Choctaw Nation. As I noted earlier, the very first page shows us young Tim, in agony, having been stung by a bee. Page after page, Clarkson's illustrations portray a modern Native family. From bright sunny pages bursting with life to the quiet ones that slow us (readers) down to absorb the stories told on that page, Clarkson's illustrations are terrific.

I particularly like the one of the family, waiting for news about the operation. The waiting room is crowded with members of their family who catch up on news and tell stories. I've spent many hours with my own family---siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles---as we waited for the outcome of a family members surgery. That large gathering often takes hospital staff by surprise when they first start working amongst Native people.

From Tingle's note at the end of the book, to the stories he tells, and Clarkson's illustrations, this book is exceptional. As I said in my earlier post today, order your copy from Cinco Puntos Press. Here, I'll say

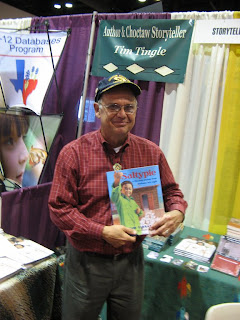

ORDER SEVERAL COPIES! And, learn more about

Tim Tingle and

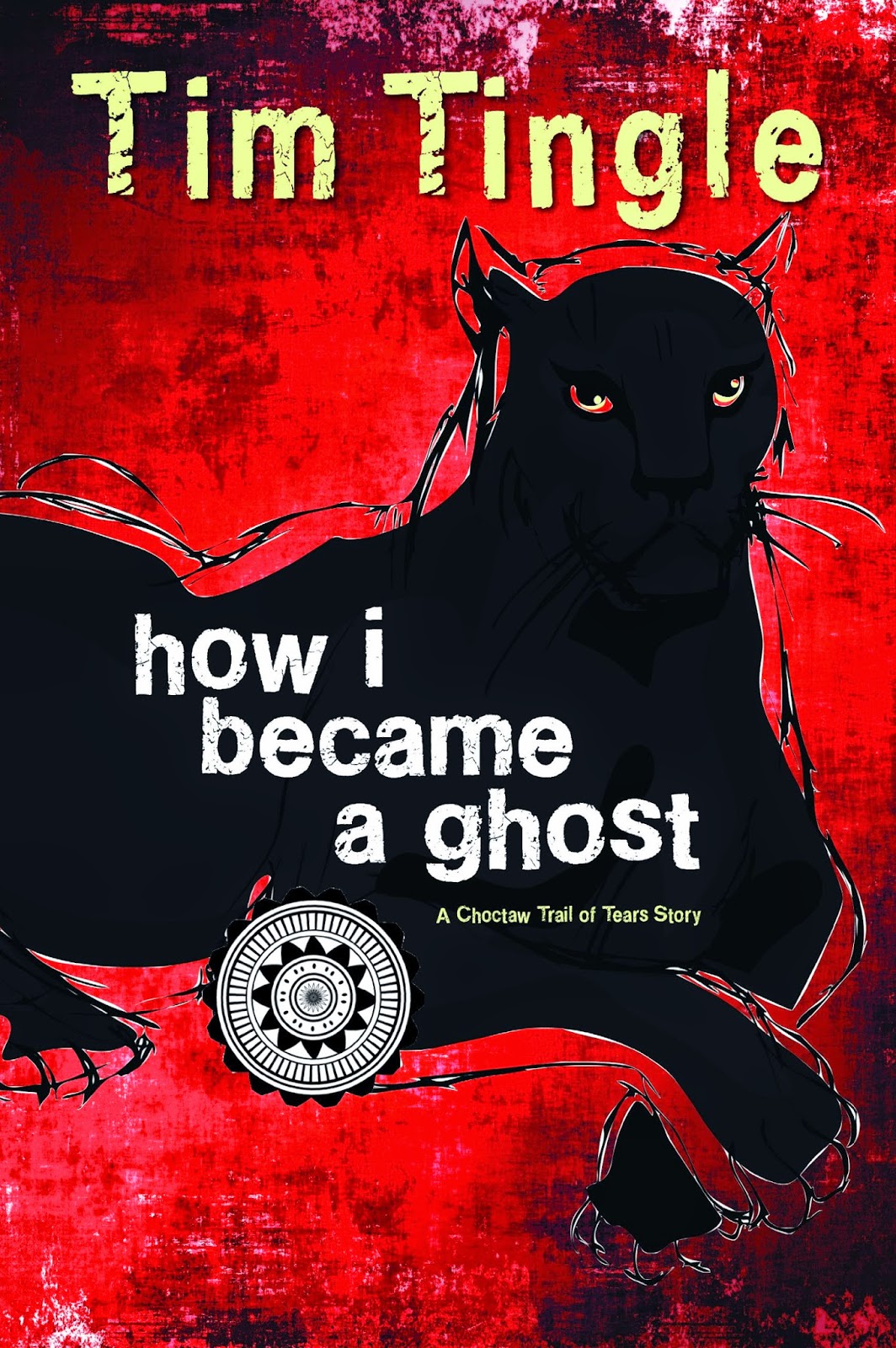

Karen Clarkson. While you're at it, order Tingle's other books, too.

Crossing Bok Chitto and

When Turtle Grew Feathers are gems.

And yes, if you're wondering, Mawmaw does regain her sight:

It was so right that my father, who had given us this word [saltypie] fifty years ago in a moment of childhood misunderstanding, would now take it away in a moment of enlightenment. He lifted his eyes and spoke.

"No more saltypie," he said. "Mawmaw can see."

The closing paragraph in this very fine book is the one I'll end this post with, too:

We all leave footfalls, everywhere we go. We change the people we meet. If we learn to listen to the quiet and secret music, as my Mawmaw did, we will leave happy footfalls behind us in our going.

We can, if we choose, leave happy footfalls, and books like this one can help us do that.