I often do a Twitter review of a book -- which means I write and send tweets as I read the book. I did that yesterday as I made my way through And Still the Turtle Watched.

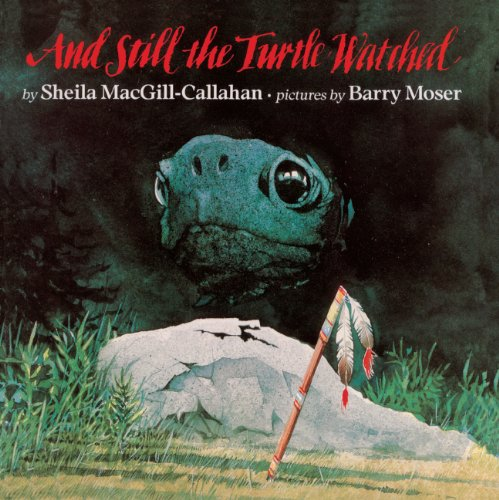

I try to compile those twitter threads here, on AICL. I usually do some light editing to make them flow a bit better than they did on Twitter. Beneath the image of the book cover and the "Not Recommended" rating, you'll find my Twitter review. It is rough--unfolding as I went. I hope it makes sense! If not, let me know.

****

This morning, I was asked about AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED. Do I recommend it? (No.)

Written by Sheila MacGill-Callahan and illustrated by Barry Moser, it came out in 1996 from Puffin Books.

I found it on an episode of Reading Rainbow. So... twitter review! There's several videos of that episode on Youtube. I don't know if RR is ok with that. As the episode opens, I see this thread is also going to critique how RR produced the segment.

It opens with Levar in a forest. The music is flute, some bells, drums... (me: sigh)

Levar says that hundreds of years ago, Indians "lived here" in a forest in western America. I hope this entire segment doesn't stay in that past tense.

Levar says white men came to their lands and took it and its riches. The forest and its creatures watched. The book in the segment (AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED) is about one of those creatures.

[Me, groaning as I continue to watch the video]... More drum and flute and then someone starts to read the book in a deep kind of fake Indian voice... [sigh] It is Michael Ansara, an actor who played a lot of "Indians" on TV and in movies. [I'm sighing but trying not to laugh, too.]

Reading Rainbow is back, isn't it? Are they on twitter???

[Goes to look....] Yeah, they are.

@readingrainbow -- please don't do this sort of thing again.

Ok, so Michael Ansara starts reading the story.

"Long ago when the eagles still built their nests along the river" (I guess they weren't doing that in 1996), an old man and his grandson stood beside a large rock. [I guess I could be glad it says "old man" and not "a shaman."

Old man says he's gonna carve that rock into turtle, who will be the eyes of Manitou. He will watch the Delaware [but... shouldn't he watch those white fellas?] and be their voice to Manitou. He tells the boy that he'll bring his children (and they'll bring their children) to that turtle. Old man got to work, making the turtle. "And then, the turtle watched" the seasons change from one to another. But he was happiest in summer when the children came, and then their children's children, and then their children's children. But as time wore on, fewer children came to greet the turtle. He wonders if he "watched badly. Does Manitou no longer hear me?"

Pausing the vid to say that the author is taking some huge liberties in writing all of this. Is it supposed to be a "myth" or a "legend"? Looked it up on WorldCat. Not seeing anything that says "Indians of North America" but there's no doubting that people think this is a Native story. With that turtle and spear on the cover, you know that's what they were going for:

Several libraries near me have it on the shelf... does it still circulate? Is it getting used in storytimes.... in your library? Or school?

Dictionaries tell me that "manitou" is a spirit or force. The author says the people in her story are Delaware. She's creating words for what she thinks is a Delaware spirit or force. She was born in the UK. Guessing she was White (she is deceased).

Back to the vid. "... one day, strangers came. They did not greet the turtle." The stranger shown is a farmer and horse. "They did not speak to Manitou." They chopped down trees; turtle watched and "does not understand." More strangers came. Now there's a city.

He watches the water turn brown; at night lights glowed "near the ground" and he can't see the stars in the sky. He gets sad. "Why watch?" he says. "My children have not come for many moons."

Then one day some boys come to the rock. They're in black leather jackets. They point at him. He gets happy. He thinks they're children who have come to see him. "Thank you, Manitou" he says. Then he heard a sound. He feels cool wetness on his eyes. He can't see anymore.

The sound is a can of spray paint.

"He cannot watch for Manitou!"

His heart cracks. Days, months, years pass. Nobody watches for Manitou.

You're supposed to feel sad. It is a sad story but it is SAPPY WHITE MAN INDIAN stuff.

Where, I wonder, did that old man's children go? They've just disappeared.

That hokey Hollywood drum beat is in the background during these sad bits. Then, a man comes! He knows the Delaware "once summered here." He's got a shovel. He hopes to find something "they left behind."

Sigh. Past tense verbs

He looked all day and found nothing. He was tired. Then he saw the rock! Covered with graffiti. The turtle didn't know the man was there. That paint had blinded his eyes. He felt the man's hand on his shell.

The man came back with workmen. They put the rock on a truck, unloaded it somewhere else. He feels them working on him. His eyes start to clear and he can hear again. He's not outdoors anymore. He's inside at a botanical garden where children come to see him. And they will bring their children and their children's children. And he "will speak of them, to Manitou."

Some of you know I caution you for making judgments on a child's identity based on what they look like. I hold to that--but in this case, I am confident in saying that the author didn't mean for us to think the kids on the last page are Native. For her, Native people are extinct.

NOW: if you're a teacher who might, in fact, have Delaware children in your class, how do you think THEY feel abt this story?

The story is over, and we're back with Levar who tells us that the Delaware people in the story chose turtle to watch because they think he is wise. He goes on to talk about other animals and "legends."

The episode shifts to a segment about eagles and people who study them. At the end, Levar is back in that forest breathing the fresh air. The RR shows ended with book recommendations. This one includes A RIVER RAN WILD (I don't rec that one either). The next recommendation is THIRTEEN MOONS ON TURTLES BACK by Bruchac. I'll have to look for that one. Update on Oct 3 2023: I no longer recommend Bruchac's work. For details, see Is Joseph Bruchac truly Abenaki?

Circling back to why I started this thread: I do not recommend AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED. It looks like a Native story, but is it, really? Or is it something the white (British) writer made up?

What happened to the Delaware people in the story? They just disappear.

But they didn't. You know that, right?

Readers are supposed to feel bad for the turtle being abandoned by the Delawares and then abused by those boys who graffitied him, but then we're supposed to feel good that a white guy rescues the turtle and puts it in a garden. But if there really was a turtle like that, I think that the Delaware people might want it left alone--not hauled off to a botanical garden. I know--ppl think "garden" and think that's fine but truly, taking Native items is a no-no. Don't do it!

A lot of writers use Native themes in stories about care of the environment. Those stories, however (and there are several) show Native people as gone. They fuel a factual error about our existence. We're still here. (And it grates to say "we're still here.")

Back with more to say about AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED. I found another video of it online. Seems that the Reading Rainbow version leaves out some of what I'm seeing in this second video.

The Reading Rainbow version doesn't include the last page, which tells readers that the turtle is in the Watson building at the New York Botanical Garden. I looked around a bit and found an article in the New York Times, dated March 25, 1988 about a box turtle petroglyph.

From the article I learned that the New York Botanical garden is huge: 250 acres. There, somewhere, a turtle petroglyph was found in 1987 by Edward J. Lenik, an archeologist from the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. An amateur archeologist had found it ten years before.

It was etched into a boulder. That's it on the left (below), as shown on the Botanical Garden website. On the right is the three-dimensional carving shown in And Still the Turtle Watched.

The NYT article says the boulder it was on had been vandalized. When they found it in 1988 they took it inside to protect it. The article suggests it was made by Delaware Indians 400-1000 years ago but also notes it could be a forger's work.

The petroglyph is small: 3 3/4 inches long by 2 1/2 inches wide. The article says they talked to someone at the American Indian Community House in NYC but it doesn't say what (if anything) they said about it.

If the botanical folks think it is Delaware, they could get in touch with the Delaware people.

All that aside, I still circle back to the idea that a non-Native woman turned that petroglyph into what looks like/sounds like a Native story.

I wonder if the Delaware people use that word (manitou) in their stories?