I did two more twitter threads on Tuesday, March 5th, and used Spooler, to combine them into this post. I've done some minor edits to fix typos.

Update, April 9, 2019: I am inserting a few photographs I took of the catalog and making small revisions so that my critique flows a bit better here than it did on Twitter. I'm also changing the style I used on Twitter for book titles (cap letters) to italics.

Monday, March 4, 2019

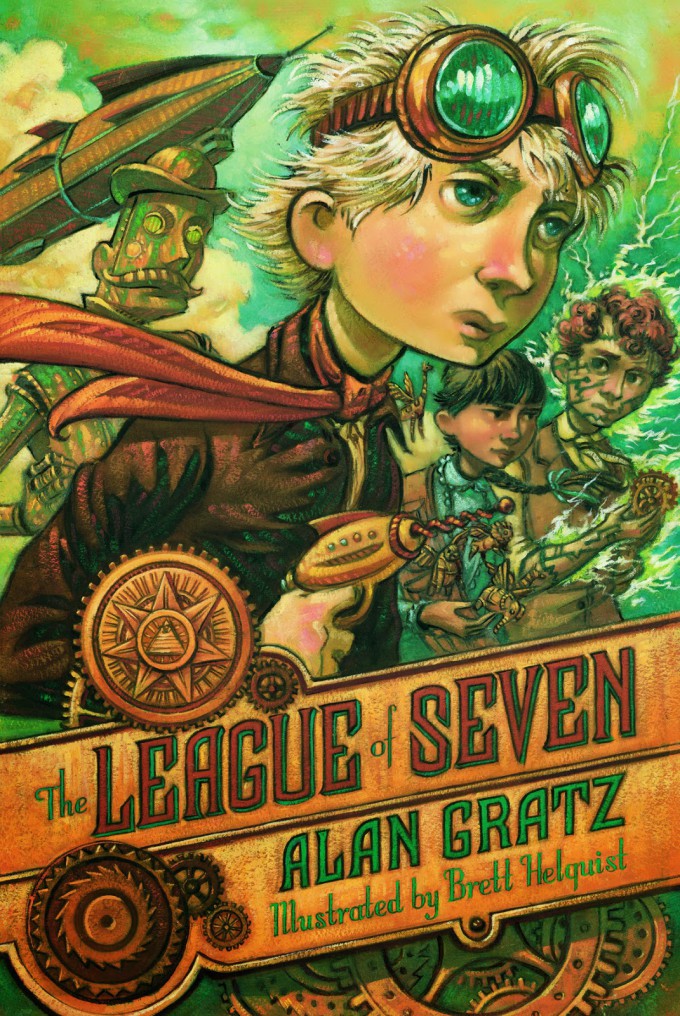

My copy of The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter by Leonard Marcus, arrived yesterday. I bought it because of the exhibit currently at the Elmer L. Anderson Library in Minnesota and concerns that the exhibit is lacking in context.

By that, I mean that the exhibit itself seems to be avoiding critical conversations about racism of some authors, like Dr. Seuss.

Sometimes, people object to critiques (like mine) that point out omissions. Their idea is that you should review what you have in front of you (in the book) rather than what you wish was there. I don't know what theoretical framework that idea comes from, but...

...I think that idea protects the status quo. It helps everybody avoid things that make them uncomfortable... that remind them of racism, for example.

Or facts like this one: You can call Europeans who came to what is currently known as the Americas "explorers" but from a Native point of view, they were invaders.

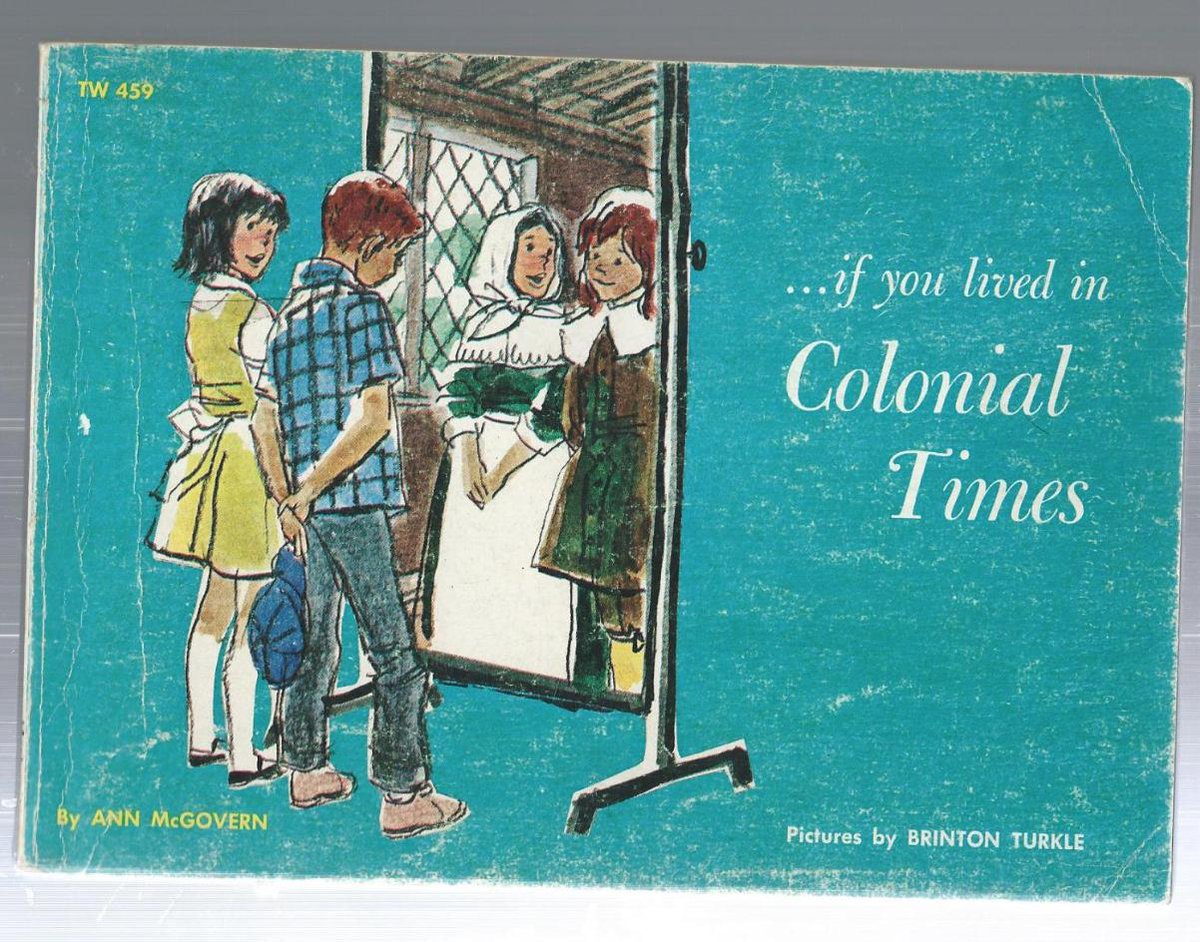

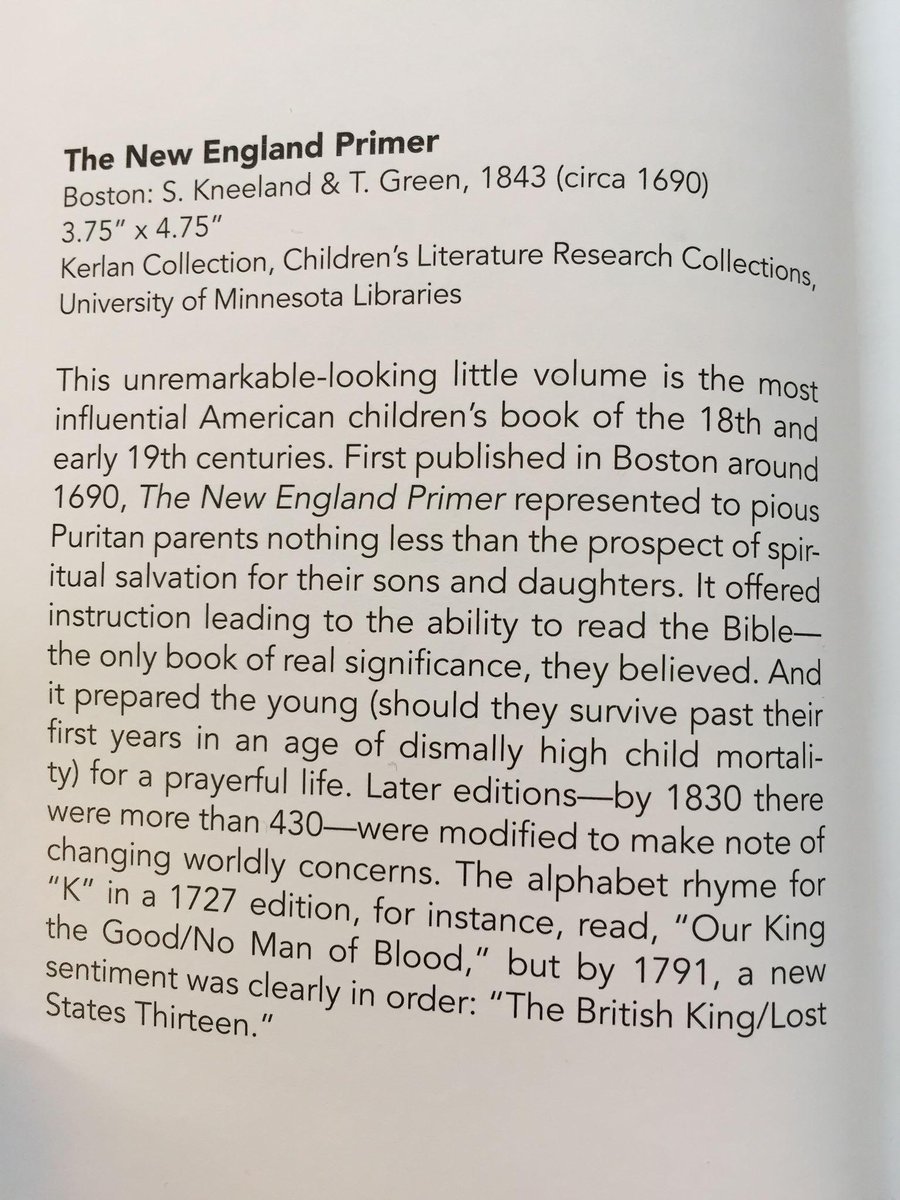

"Visions of Childhood" is the first section of The ABC of It. Its first subsection is "Sinful or Pure? The Spiritual Child." It begins with the Puritans. Cotton Mather. The book: The New England Primer. Obviously, I can't fault Marcus for what the Puritans left out of that book.

But it is fair, I think, to ask for more than what he offers in his description of the book (see below). What would it feel like, for example, if he included something about the Native Nations and people whose lands the Puritans were invading?

In the last sentences (of the description), Marcus noted that later editions were changed "to make note of changing worldly concerns." He notes, specifically, changes to the "K" rhyme:

1727 edition: "Our King the Good/No Man of Blood"

1791 edition: "The British King/Lost States Thirteen."Marcus is able to address specific "changing worldly concerns." He notes revisions that actually got done from the 1727 to the 1791 editions.

Couldn't he insert something in his description about Native peoples? or slavery?

Without that, he is giving readers of the catalog (and if the actual exhibit is similar to the book) his version of the All White World of Children's Books.

Have you been to the exhibit at the Anderson library? Does it have the New England Primer on display? The "sinful or pure" section includes William Blake's Songs of Innocence on the next two pages.

Next is "A Blank Slate: The Rational Child." Marcus begins by writing about Orbis Pictus by Comenius and Some Thoughts Concerning Education by John Locke.

Next is "A Blank Slate: The Rational Child." Marcus begins by writing about Orbis Pictus by Comenius and Some Thoughts Concerning Education by John Locke.

Those of you in children's lit know that, in 1989, the National Council of Teachers of English established the Orbis Pictus Award to honor Comenius's book. You can see Orbis Pictus, online.

Marcus's book, The ABC of It, has two photos of interior pages of Comenius's book. Each takes up half a page. One is the title page and image of Comenius; the other is "Fruits of Trees." The description for the two pages is:

"Although spiritual matters received due attention in Comenius's "pictured world," his most famous book gave pride of place to worldly matters--geography, weather, place [...] among others."

I wish the pages about spiritual matters received attention by Marcus! It would have let readers/exhibit visitors see Comenius's point of view of those spiritual matters. Go here to see. He wrote: "Indians, even to this day, worship the Devil."

Including that page would have made for some really interesting conversations there at the exhibit. Lest you try to wave Comenius's words away as a "product of his time," missionaries are still at work, today.

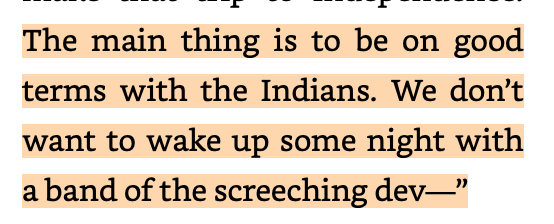

And, children's books that are read today--like Little House on the Prairie--have characters with that point of view, too. Here's Pa (who so many people think is the good guy, sympathetic to Native ppl):

|

| Excerpt from Little House on the Prairie |

One thing that many of us (scholars) ask is "who edited this book" because we think editors should catch problems (in this case, an editor with an eye towards whitewashing and racism might have asked Marcus to provide a more critical description of some of these books). I'm wondering that as I page through Marcus's The ABC of It. Who was his editor?

The next subsection is "From Rote to Rhyme." In it, there are 4 illustrations of McGuffey's Reader. Here's the first double-paged spread, with three of the illustrations on the right side:

The next subsection is "From Rote to Rhyme." In it, there are 4 illustrations of McGuffey's Reader. Here's the first double-paged spread, with three of the illustrations on the right side:

And here's the second double-paged spread:

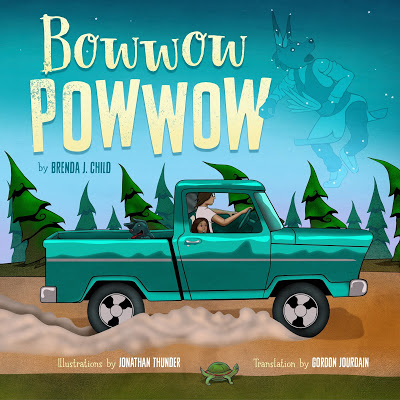

As you can see, on the left is a full page image of one page from inside a McGuffey reader. Facing it is a page with the cover of the Indian readers by Ann Nolan Clark (Singing Sioux Cowboy; see "To Remain an Indian" for a Native POV on the readers), and the covers for Bowwow Powwow and the English and Ojibwe covers for When the White Foxes Came. Marcus includes a description of the Clark book (here's an enlarged copy of the description beneath the cover of Singing Sioux Cowboy):

See? He describes the white-authored book, but includes nothing other than the citation information for the Native-authored books on that page.

As you can see, on the left is a full page image of one page from inside a McGuffey reader. Facing it is a page with the cover of the Indian readers by Ann Nolan Clark (Singing Sioux Cowboy; see "To Remain an Indian" for a Native POV on the readers), and the covers for Bowwow Powwow and the English and Ojibwe covers for When the White Foxes Came. Marcus includes a description of the Clark book (here's an enlarged copy of the description beneath the cover of Singing Sioux Cowboy):

See? He describes the white-authored book, but includes nothing other than the citation information for the Native-authored books on that page.

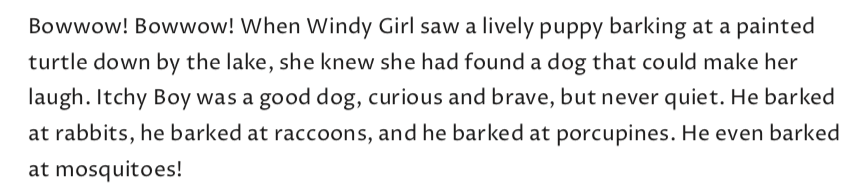

Those three covers are books by Native writers. I have lot of questions. Why are they in this "From Rote to Rhyme" section? Here's the opening paragraph for Brenda Child's Bowwow Powwow:

See? There's no rhyme there. Did Marcus read the book? Did he make a judgement about the contents about the book because the title rhymes?

Bowwow Powwow is excellent, by the way, and if I was doing that ABC book, I'd have cut some of the McGuffy pages so it could have more space.

The other Native-authored book on that page is When the White Foxes Came. I don't know that bk, but I do know some of the people (Margaret Noodin and Mary Hermes) who put it together. Marcus included the English and Ojibwe covers, which is good but I'd rather see less of McGuffey and more of Native writers.

Next in that section is page 28, about Theodor Geisel (Dr Seuss). There's a photo of him and the covers of The Cat in the Hat and The Cat in the Hat Comes Back. Those bks rhyme, so it makes sense that they'd be in this section of Rote and Rhyme. But, in the accompanying text, there is no mention of Seuss's racist cartoons.

Seuss is in the news a lot of late because of this article: The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books. If you listen to NPR you heard abt it. If you read People (the news and entertainment magazine), you saw it there.

If you see the exhibit at the Elmer L. Anderson Library, what do you notice about its POV? Its whiteness? I welcome your observations.

Tuesday, March 6, 2019

Starting Day 2 of my review of Leonard Marcus's The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter. I read up to page 29 yesterday.

The next subsection of "Visions of Childhood" is "The Work of Play: The Progressive Child." It begins with Lucy Sprague Mitchell's Here and Now Story Book. In my doctoral studies, I read abt her, the Bank Street school, and her ideas about what children need, in their bks.

Mitchell said that kids need "here and now" rather than fairy tales. In The ABC of It, Marcus includes the cover of Mitchell's book, the intro (which says the stories in the book are "experiments in content and form"), and "Marni Takes A Ride in A Wagon."

You can see Mitchell's Here and Now Story Book here (in original format) and here (transcribed). It was published in 1921.

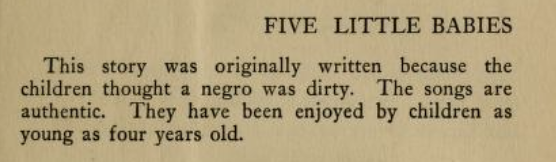

On page 290 is "Five Little Babies." It is racist, as you'll see. The intro to it says:

"This story was originally written because the children thought a negro was dirty. The songs are authentic. They have been enjoyed by children as young as four years old."

|

| Screen cap of Five Little Babies |

In his description of Mitchell's book, Marcus doesn't mention its racist contents. Yesterday's thread on his bk, The ABC of It, is meant to ask questions about what gets put into books about children's books--and what is left out.

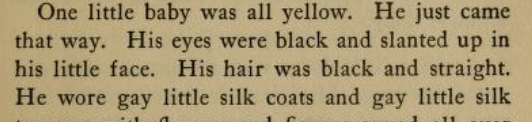

In the Five Little Babies (that Marcus didn't include), there's a "yellow" baby "in China", a "brown" baby "in India," a "black" baby "in Africa" and a "red baby" who was an "Indian baby" who lived "long, long ago" in America... And of course, a "white" baby that is "in your own country every day and he is a little American baby."

|

| Screen cap of Five Little Babies |

The physical descriptions for the babies are racist. "Slanted" eyes, "kinky" hair and wearing "a loincloth" or nothing at all.

American babies have white skin, blue eyes, and gold hair.

Mitchell wrote Native ppl out of existence, and placed all others, elsewhere on the globe (not in the U.S.).

American babies have white skin, blue eyes, and gold hair.

Mitchell wrote Native ppl out of existence, and placed all others, elsewhere on the globe (not in the U.S.).

You know that Native people exist, today, right? Surely Mitchell knew that, too.

And you know that in 1921, the US wasn't populated exclusively by people with white skin, blue eyes and gold hair. Surely, Mitchell knew that as well.

So, how do we explain Mitchell's "Five Babies"?! And why did Marcus choose not to refer to that story in Mitchell's book?

And you know that in 1921, the US wasn't populated exclusively by people with white skin, blue eyes and gold hair. Surely, Mitchell knew that as well.

So, how do we explain Mitchell's "Five Babies"?! And why did Marcus choose not to refer to that story in Mitchell's book?

These are the kinds of questions that an exhibit at an institution like University of Minnesota's Elmer L. Anderson library ought to engage with, in some way.

In January, Lisa Von Drasek (the curator) gave an interview to Betsy Bird at Fuse 8 (Bird's blog at School Library Journal) about the exhibit. In the interview, Von Drasek said

In January, Lisa Von Drasek (the curator) gave an interview to Betsy Bird at Fuse 8 (Bird's blog at School Library Journal) about the exhibit. In the interview, Von Drasek said

"U of M is a land grant university. This is important because our mission is to research, create, and disseminate knowledge."

From what I see so far there seems to be a choice about what knowledge the exhibit disseminates.

It seems like The ABC of It -- the physical exhibit and the book (catalog) of it -- are in that "warm fuzzy" space that is very white and best characterized as nostalgia.

Why did Marcus avoid telling us that Geisel did racist work? And that Mitchell created racist stories?

Why did Marcus avoid telling us that Geisel did racist work? And that Mitchell created racist stories?

Obviously, THAT is not the point of the exhibit.

So, what IS the point?

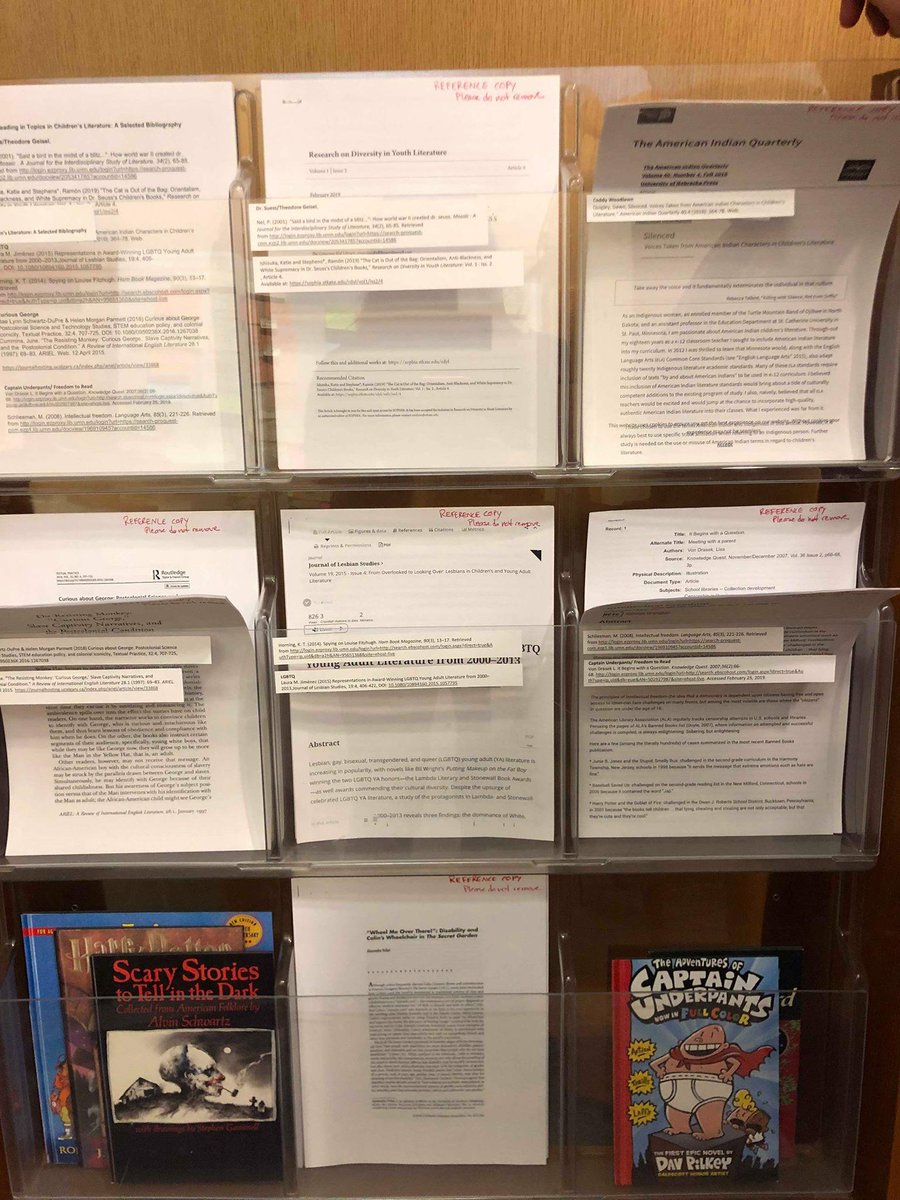

The exhibit opened on February 27th. Over in a corner, there is a rack of articles that has a copy of the Seuss article by Ishizuka and Stephens, "The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books" but...

So, what IS the point?

The exhibit opened on February 27th. Over in a corner, there is a rack of articles that has a copy of the Seuss article by Ishizuka and Stephens, "The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books" but...

... why can't excerpts from the article be part of the exhibit that has the Seuss books?

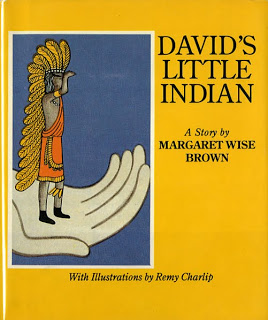

Marcus tells us that Margaret Wise Brown was Mitchell's "literary protégée" (p. 30). On page 33, he gives us covers of three of her books (The Noisy Book; The Seashore Noisy Book; The Indoor Noisy Book). Pages 34-37 (four entire double-paged spreads) are devoted to Goodnight Moon. He could have shown us one of her racist books (David's Little Indian) but he didn't.

Marcus writes that Maurice Sendak put Mitchell's ideas to work in his books. On page 38, he includes Ruth Krauss books that Sendak illustrated. Sendak is a towering figure in kidlit. But he also did lot of stereotypical Indians AND...

What was he doing with a feather on his head?! Go here for details.

Next up in "Visions of Childhood" is "Building Citizens: The Patriotic Child." It starts w/ Noah Webster's The American Spelling Book. Marcus writes that Webster "yearned for an American English purged of what he believed to be the excesses of British aristocratic influence."

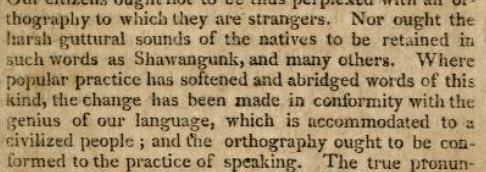

On p. 42 are the cover and two interior pages from The American Spelling Book and a print of Webster titled "The Schoolmaster of the Republic." So... what did that schoolmaster have to say about Native words?

Webster didn't want British influence, and he didn't want "guttural sounds of the Natives" either. Marcus felt it important to note that Webster didn't want British influence but Marcus chose to ignore what Webster said about Native language.

|

| "gutteral sounds of the Natives" screen cap from Webster's spelling book. |

On page 45, Marcus has Ann Nolan Clark's In My Mother's House. Its illustrations are by Velino Herrera of Zia Pueblo (published in 1941). Marcus writes that Clark worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and that her bks played a key role in the US governments "new, more culturally respectful approach to the education of Native American children." There are several of these books, most written by Clark and with illustrations by Native artists. (See "To Remain an Indian" for some discussion of the books.)

I'm glad to see that Marcus included In My Mother's House but wonder what it looks like in the physical exhibit. Do people who see it know what preceded this more "respectful approach"? Do they know about the 'kill the Indian and save the man' philosophy of the US government schools for Native kids?

I hope #DiversityJedi see the exhibit (or the book/catalog about it) and offer critiques of content for which they have expertise. There's a lot I don't know anything about. On page 48-49, for example, Marcus shows comic books published in Mumbai.

On page 52 is a new subsection, "Down the Rabbit Hole," which is about Alice in Wonderland. Marcus gives eight pages to it.

Update on Thursday, March 7th: A colleague wrote to tell me that the Amar Chitra Katha stories that Marcus has in his book on page 48 and 49 are racist. She recommends an article in The Atlantic by Shaan Amin: The Dark Side of the Comics that Redefined Hinduism, published on December 30, 2017. About the series, Marcus's description says that these comics "introduced tens of millions of English-speaking predominantly middle-class Indian youngsters to their religious and cultural roots."

On page 52 is a new subsection, "Down the Rabbit Hole," which is about Alice in Wonderland. Marcus gives eight pages to it.

A new section starts on p. 60: "In Nature's Classroom: The Romantic Child." On p. 67 is Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are. (Image below is from my blog post about the image and book.)

Pages 68-69 are about E.B. White. About Charlotte's Web, Marcus writes: "In the atomic age, he [White] recognized, the earth was perishable and in need of protection. What could save it? Wise leaders like Charlotte, or a world forum like this story's barnyard, where even a rat may realize the sense of keeping the web intact."

E.B. White did some stereotyping of Native people in Stuart Little and in Trumpet of the Swan (are you getting a good sense of how many esteemed and famous writers/people in children's literature held/hold stereotypical views?!):

|

| Excerpt from Trumpet of the Swan |

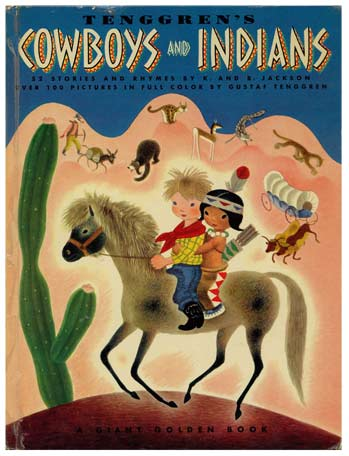

The remaining pages in this section are about Hans Christian Andersen and Gustaf Tenggren. Several years ago, Marcus did a book about the Little Golden Books, so he probably saw Tenggren's Cowboys and Indians, but he chose not to include it in The ABC of It.

It may be that Cowboys and Indians isn't in The ABC of It because that art is not in the Kerlan. Marcus could have noted it, somewhere in the book. And, it could be noted in the physical exhibit.

Tuesday, March 7 -- late afternoon

Day 2-late afternoon thread on The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter, a physical exhibit (and companion book/catalog) at the Anderson Library at the University of Minnesota.

I did a thread yesterday and one this morning and am doing this one because tomorrow (Wed) night, Shannon Gibney is on a panel, there, about the exhibit.

Shannon does some terrific work on issues of representation and misrepresentation. One of her areas of interest/expertise is about Native peoples.

I was paging through The ABC of It and noticed the Wizard of Oz pages in the "Art of the Picture Book" section of Marcus's book.

There are two pages on The Wizard of Oz.

The accompanying text notes that L. Frank Baum had been an actor, a farmer, and ... a newspaper editor. Marcus knows that Baum was a newspaper editor. I am going to assume he knows about the newspaper editorials that Baum wrote.

The accompanying text notes that L. Frank Baum had been an actor, a farmer, and ... a newspaper editor. Marcus knows that Baum was a newspaper editor. I am going to assume he knows about the newspaper editorials that Baum wrote.

He doesn't mention the contents of Baum's editorials, but I think he should have. You may know about them if you listened to this NPR story in 2010. In one of his editorials, Baum called for "the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians."

Marcus and Lisa Von Drasek could have created a way for visitors to "speak back" to that editorial--if they had included it.

These aren't abstract or academic concerns. Native people know about Baum's editorials. We don't have a warm fuzzy for Oz.

These aren't abstract or academic concerns. Native people know about Baum's editorials. We don't have a warm fuzzy for Oz.

Native people who come to the exhibit will see Baum, glorified.

In many places (books/articles/online), there are conversations that tell ppl to keep the art and the artist separate. That's handy for some. It doesn't work for me, and it doesn't work for others, either.

In many places (books/articles/online), there are conversations that tell ppl to keep the art and the artist separate. That's handy for some. It doesn't work for me, and it doesn't work for others, either.

In her 2018 novel, Hearts Unbroken, Muscogee Creek writer Cynthia Leitich Smith takes up that "separate the art from the artist" idea. Her book is set in a high school that is doing an Oz play. Lou (the main character) and Hughie (Lou's brother) are citizens of the Muscogee Nation.

Their mom is in law school and is especially interested in protecting the rights of Native children via the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Their mom knows about the Baum editorials.

Their mom knows about the Baum editorials.

When Hughie (Lou's brother) learns about them, he has a hard time deciding what to do. Go ahead and do the play? What is the cost to him, emotionally, if he goes ahead?

Smith lays all that out in her book.

Smith lays all that out in her book.

The ABC of It book/catalog for the exhibit avoids Baum's editorials. It looks the other way. The exhibit is in Minnesota. It looks away from racism, on land that once belonged to Native people.

There are eleven tribal nations located in Minnesota.

There is an American Indian Studies department at the University of Minnesota.

What does this exhibit's treatment of Oz/Baum tell the faculty, their students, their children?

There is an American Indian Studies department at the University of Minnesota.

What does this exhibit's treatment of Oz/Baum tell the faculty, their students, their children?

****

I may continue my review of The ABC Of It but wanted to bring what I've done so far on Twitter, here, because AICL is where I publish most of my writing.