Bo wants to find the perfect container to show off his traditional marbles for the Cherokee National Holiday. It needs to be just the right size: big enough to fit all the marbles, but not too big to fit in his family's booth at the festival. And it needs to look good! With his grandmother's help, Bo tries many containers until he finds just the right one. A playful exploration of volume and capacity featuring Native characters and a glossary of Cherokee words.

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materi...

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

Saturday, February 12, 2022

Art Coulson and Madelyn Goodnight's LOOK GRANDMA! NI, ELISI! featured in Reading Rainbow Live

Tuesday, December 28, 2021

Highly Recommended: THE FIRE by Thomas Peacock

Written by Thomas Peacock (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe)

Illustrations by Anna Granholm

Published by Black Bears & Blueberries

Published in 2021

Reviewer: Jean Mendoza

Review Status: Highly Recommended

This story is a fictionalized account of the Great Fire of 1918 based on an interview of Elizabeth (Betty) Gurno, a Fond du Lac Reservation elder. Betty was a little girl when the fire swept the area. The Fire of 1918 destroyed the city of Cloquet, Minnesota and surrounding communities, including the Fond du Lac Reservation, and resulted in the loss of many lives.

Author Thomas Peacock frames Betty's telling of the story within a later-day classroom scene in Minnesota. Betty has come to her grandchild's classroom to share her memories of the fire.

First reason to recommend The Fire: It focuses on Indigenous people's experience during a catastrophic event, and joins a fairly small pool of exciting and moving historical fiction picture books told from an Indigenous perspective. In The Fire, Ojibwe oral history is at the center. The author uses some words in Ojibwemowin and refers to Ojibwe traditions (such as offering asemaa, tobacco, to an elder who shares wisdom).

Second reason: It's timely. Wildland fires have affected communities around the country in recent years. Children are wondering how such fires can happen, how people survive them, and what happens afterward. Young readers may want to do further research about the Great Fire of 1918, using sources like the National Weather Service article and a dedicated page on the Library of Congress Web site.

Third reason: The illustrations amplify the storytelling. There's plenty of drama in the pictures. Burning boards fly through the air; dozens of animals join the people in the river as the fire rages. But there are also some important, more subtle touches. Look closely at the page that shows Betty's grandparents warning her family about the fire. The hazy trees and yellowish sky behind the horse and buggy aren't just meant to be pretty. That's the smoke, already drifting into Fond du Lac, a silent warning.

Fourth reason: The story manages to locate modest, honest hope and affirmation in the aftermath of the disaster. Readers learn that no Ojibwe people died, but "more than four hundred fifty of our non-Native neighbors were lost in the fire," and several non-Native towns burned to the ground. (For comparison, I checked the estimated death toll of the Chicago Fire of 1871 -- around 300.) Grandma Betty recounts that her grandmother's home escaped the fire, and she shared what food she had with other Fond du Lac families, most of whom had lost everything. I love the final words of Grandma Betty's storytelling: "We help each other. That is what we do." (It reminds me of the values behind Richard Van Camp's little board book, May We Have Enough to Share.)

I also love that when Betty ends her storytelling, the children line up to hug her. Maybe that's a classroom custom. But I think it also shows that the children are moved by this elder's story of the trauma she and their community endured, and they are caring for her in their way, years afterward.

The Fire is a valuable book to have on your shelves, and to share with children you know.

Monday, December 20, 2021

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: THE SEA IN WINTER

By Christine Day (Upper Skagit)

Back in September 2020, Debbie blogged about her positive reaction to reading the ARC of Christine Day's second novel for young people -- The Sea in Winter. Since then, the book has gotten positive critical attention, including a Kirkus starred review and School Library Journal "Best Book". Here, finally, is my "short and sweet" AICL review.

The publisher, Heartdrum, says this about The Sea in Winter:

It’s been a hard year for Maisie Cannon, ever since she hurt her leg and could not keep up with her ballet training and auditions. Her blended family is loving and supportive, but Maisie knows that they just can’t understand how hopeless she feels.... Maisie is not excited for their family midwinter road trip along the coast, near the Makah community where her mother grew up. But soon, Maisie’s anxieties and dark moods start to hurt as much as the pain in her knee. How can she keep pretending to be strong when on the inside she feels as roiling and cold as the ocean?

Reason One to recommend The Sea in Winter: The sense of place.

The author writes from the heart when she describes the story's setting. It's good to have a book about a contemporary middle schooler, that celebrates geoduck clams and the removal of the Elwha River dam. It's set in much the same part of the continent as a certain popular vampire-and-werewolf series, but Day's storytelling is noticeably more attuned to the landforms, the weather, the animals, the sea.

Reason Two: Respect for advocacy and activism.

Advocacy for social and environmental justice, and for Indigenous rights, are natural parts of family life in Maisie's world. For example, readers learn that her family has been directly affected by treaty rights to harvest shellfish, and removal of dams that kept salmon from spawning in local rivers. And conflict around the 1999 Makah whale hunt (the tribe's first effort to hold its traditional hunt in 70 years) forced an important decision for some of Maisie's Makah relatives.

Reason Three: The protagonist's unique perspective.

The Sea in Winter offers the young reader a window on the experience of a child with an unusual level of ambition. Most children Maisie's age haven't discovered an activity that inspires the kind of commitment she has to ballet. What is it like, at age 12, to have your entire life, including peer friendships, revolve around ballet, because you love it that much? Who else understands such dedication? And how do you cope, at age 12, when you face the loss of your beautiful dream? Is that what depression feels like?

Reason Four: Maisie's solid, loving Native family.

Leo Tolstoy famously, or infamously, wrote, "All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." Though Maisie's family faces some challenges, including Maisie's depression, they are fundamentally "happy" together -- affectionate, thoughtful, supportive, respectful of boundaries, and knowledgeable about their Native identities. But they're by no means ordinary, stereotypical, or indistinguishable from other fictional families that are doing essentially okay. The author makes them interesting, not merely quirky or weird, as individuals and as a unit.

In short, I add my voice to the chorus of recommendations: Read and share The Sea in Winter with young people in your life!

Tuesday, November 30, 2021

Highly Recommended: ON THE TRAPLINE by David A. Robertson and Julie Flett

Ininimowin means "Cree language."

Monday, November 29, 2021

Highly Recommended! CLASSIFIED:THE SECRET CAREER OF MARY GOLDA ROSS, CHEROKEE AEROSPACE ENGINEER, by Traci Sorell and Natasha Donovan

Sunday, November 28, 2021

Highly Recommended: THE OTHER TALK: RECKONING WITH OUR WHITE PRIVILEGE by Brendan Kiely

The facilitators were about to move on to their next exercise when a Native American woman in the audience stood up. She wanted to know why the racetrack model, why the entire workshop, did not include or allude to, in any way, Indigenous people in the United States. "This," she went on to explain, "is the kind of erasure we face every day."

Highly Recommended! LOOK GRANDMA! NI, ELISI! by Art Coulson; illustrated by Madelyn Goodnight

Saturday, November 27, 2021

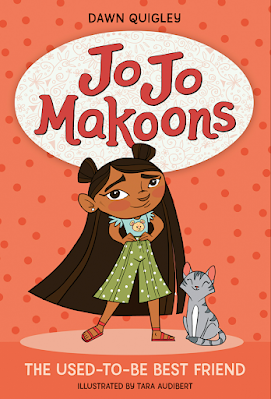

Highly Recommended: JO JO MAKOONS, THE USED-TO-BE BEST FRIEND by Dawn Quigley; illustrations by Tara Audibert

Hello/Boozhoo—meet Jo Jo Makoons! Full of pride, joy, and plenty of humor, this first book in an all-new chapter book series by Dawn Quigley celebrates a spunky young Ojibwe girl who loves who she is.

Jo Jo Makoons Azure is a spirited seven-year-old who moves through the world a little differently than anyone else on her Ojibwe reservation. It always seems like her mom, her kokum (grandma), and her teacher have a lot to learn—about how good Jo Jo is at cleaning up, what makes a good rhyme, and what it means to be friendly.

Even though Jo Jo loves her #1 best friend Mimi (who is a cat), she’s worried that she needs to figure out how to make more friends. Because Fern, her best friend at school, may not want to be friends anymore…

Do you wanna know what mooshoom means? It means "grandpa" in the Michif language.

Try saying: "Jo Jo Makoons Azure nindizhinikaaz."

My girl, shots help you to be healthy. There are many sicknesses out there, and shots give good protection.

Sunday, November 14, 2021

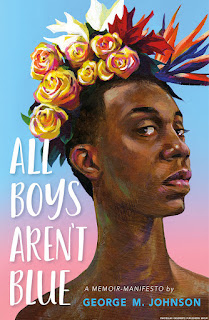

Highly Recommended: ALL BOYS AREN'T BLUE: A MEMOIR-MANIFESTO by George M. Johnson

In a series of personal essays, prominent journalist and LGBTQIA+ activist George M. Johnson explores his childhood, adolescence, and college years in New Jersey and Virginia. From the memories of getting his teeth kicked out by bullies at age five, to flea marketing with his loving grandmother, to his first sexual relationships, this young-adult memoir weaves together the trials and triumphs faced by Black queer boys.

Both a primer for teens eager to be allies as well as a reassuring testimony for young queer men of color, All Boys Aren't Blue covers topics such as gender identity, toxic masculinity, brotherhood, family, structural marginalization, consent, and Black joy. Johnson's emotionally frank style of writing will appeal directly to young adults.

... American Indians sharing food with the Pilgrims at the first Thanksgiving.

*takes deep breath*

What it doesn't show is that the Pilgrims stole the American Indians' food when they first arrived on the Mayflower, because they weren't prepared for winter.

We learned that Abraham Lincoln wasn't all he was cracked up to be. We learned about the Emancipation Proclamation, but also read some of the statements he made that weren't in the history books. The ones that were disparaging toward Black Americans and the fight for equality.

We learned that Lincoln had many thoughts that never seemed to make it into the pages of the history books.

He shares some of those statements made by Lincoln, including this one (p. 94):

"My paramount object in this struggle is to save the Union, and is not either to save or to destroy slavery. If I could save the Union without freeing any slave I would do it, and if I could save it by freeing all the slaves I would do it; and if I could save it by freeing some and leaving others alone, I would also do that."

Sunday, October 31, 2021

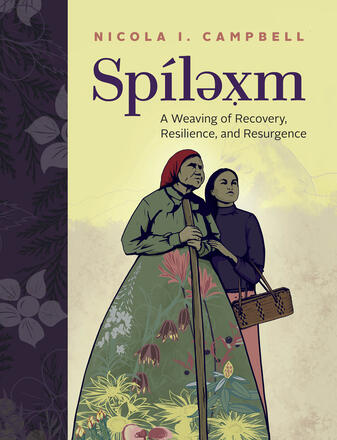

Highly Recommended! Spílexm: A Weaving of Recovery, Resilience, and Resurgence, by Nicola I. Campbell

Spílexm: A Weaving of Recovery, Resilience, and Resurgence

If the hurt and grief we carry is a woven blanket, it is time to weave ourselves anew.

In the Nłeʔkepmxcín language, spíləx̣m are remembered stories, often shared over tea in the quiet hours between Elders. Rooted within the British Columbia landscape, and with an almost tactile representation of being on the land and water, Spíləx̣m explores resilience, reconnection, and narrative memory through stories.

Captivating and deeply moving, this story basket of memories tells one Indigenous woman’s journey of overcoming adversity and colonial trauma to find strength through creative works and traditional perspectives of healing, transformation, and resurgence.

Prairie LettersHer Blood is from SpetetkwMétisNłeʔkepmxcín LullabyLand TeachingsComing to my Sensessorrowyemít and merímstnthis body is a mountain, this body is the landResurgence

Monday, October 25, 2021

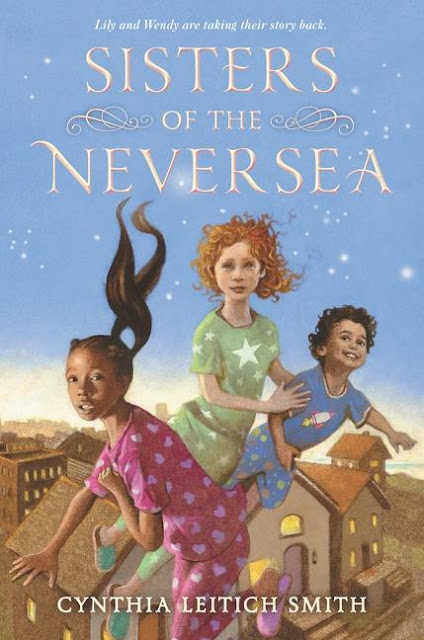

Highly Recommended: SISTERS OF THE NEVERSEA by Cynthia Leitich Smith; cover art by Floyd Cooper

Today AICL is pleased to give a Short and Sweet Rec* to Cynthia Leitich Smith’s Sisters of the Neversea. We recommend you get it for your children, your classroom, or your library. Here’s the description:

Lily and Wendy have been best friends since they became stepsisters. But with their feuding parents planning to spend the summer apart, what will become of their family—and their friendship?

Little do they know that a mysterious boy has been watching them from the oak tree outside their window. A boy who intends to take them away from home for good, to an island of wild animals, Merfolk, Fairies, and kidnapped children, to a sea of merfolk, pirates, and a giant crocodile.

A boy who calls himself Peter Pan.

Four reasons why AICL recommends Sisters of the Neversea

First, the author is Native. Cynthia Leitich Smith is a citizen of the Muscogee Nation, telling us a story where the primary character is Muscogee Creek.

Second, Sisters of the Neversea shows readers who Native people are, for real. J.M. Barrie’s stories about Peter Pan have mis-informed generations of readers. His stories encourage others to play Indian in stereotypical ways, and the characters in his story that are meant to be Native (Tiger Lily) are straight-up stereotypes. We are nothing like the “Indians” in his stories. Smith’s take on Peter Pan pushes back on those stereotypes.

Third, Sisters of the Neversea includes Black Indians. Upon seeing Floyd Cooper's cover art, Smith writes that she thought "There you are!" With his art, she saw Lily as Black Muscogee. Later in the book, we meet Strings, a Black Seneca Indian from the Bronx.

Fourth, Smith's author’s note includes several questions that she poses about the Native people in Barrie’s stories. “How did they get there?” she asks, and “Why were they described in hurtful language?” are two of them. Teachers who use the book in the classroom can draw attention to those questions and encourage students to ask similar questions about Native characters in other books they read.

We hope you’ll get a copy ASAP, read it, and tell others to read it, too. When you’re at your local library, ask for it! If they don’t have it yet, ask them to order it.

-----

*A Short and Sweet Rec is not an in-depth analysis. It is our strategy to tell you that we recommend a book we have read. We will definitely refer to it in book chapters and articles we write, and in presentations we do. Our Short and Sweet Recs include four reasons why we recommend the book.

Friday, September 17, 2021

Highly Recommended! THE DINE READER: AN ANTHOLOGY OF NAVAJO LITERATURE

"When I paint people reading, it's also beyond what the picture is, it keeps going on. It's an interpretation of an interpretation of a reader."

Monday, September 06, 2021

Highly Recommended! SHARICE'S BIG VOICE: A NATIVE KID BECOMES A CONGRESSWOMAN

Indigenous sovereignty is an essential component of civics education.

Elementary social studies curriculum is notoriously silent about Indigenous sovereignty.

Wednesday, May 12, 2021

Highly Recommended! I SANG YOU DOWN FROM THE STARS, written by Tasha Spillett-Sumner; illustrated by Michaela Goade

Family and friends came from near and far to welcome you.One by one, they held you and greeted you.

Monday, May 10, 2021

Thinking Critically About Writing Assignments We Ask Children to Do [and a recommendation for TEACHING CRITICALLY ABOUT LEWIS AND CLARK by Schmitke, Sabzalian, and Edmundson]

Dear Diary,I am so mad! I took 3 annoying men who were very stinky to find the best rout to the Pacific Ocean, found horses, food, and peace so tribes wouldn't attack us! I did that whole journey, but the thing is I did most of the work, not Lewis, or Clark, or my husband! It should have been called the Sacagawea expedition!! I DID THIS ALL WITH A BABY ON MY BACK YET THE MEN DID MORE COMPLAINING!! And I got zero $! Like come on! I'm never doing that again.

Wednesday, May 05, 2021

Highly Recommended: MII MAANDA EZHI-GKENDMAANH / THIS IS HOW I KNOW, written by Brittany Luby; illustrated by Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley [and a note about translators]

Aaniish ezhi-gkendmaanh niibing?How do I know summer is here?

Mii maanda ezhi-gkendmaanh niibing.This is how I know summer.