- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

- Debbie on Social Media

- 2024 American Indian Literature Award Medal Acceptance Speeches

- Native Removals in 2025 by US Government

Saturday, March 11, 2023

Another New Cover for Frank Asch's POPCORN

Tuesday, March 07, 2023

"Could he still use the youth edition of 'An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States'?"

Monday, March 06, 2023

Debbie--have you seen SWIFT ARROW by Josephine Cunnington Edwards?

On January 1, 1984, a small home in Harrisville, New Hampshire, became the maiden office of TEACH Services, Inc. The mission of the newly formed publishing company was to encourage and strengthen individuals around the world through the distribution of books that point readers to Christ.

Colored leaves, red, yellow, and brown, fluttered past George as he rode behind Woonsak in the long string of Indians and ponies. They were riding north and moving quickly. So many Indians moved along the path that George, who rode near the front of the line, could not see the end when he turned around to look. The farther they went, the more unhappy George became. For with every step, Neko (his faithful pony) took him farther and farther from his home and from Ma and Pa. Even the fluttering leaves seemed like little hands waving good-bye all the day long. So begins chapter seven of this beloved classic by Josephine Cunnington Edwards. George, a young pioneer boy is captured by Indians and raised as the son of a mighty chief. He spends his time learning the ways of these native Americans, and yearning for the day that he might find a way to return to his loving family.

Wednesday, March 01, 2023

"Presenter Self-identification Statement" at 2023 Tucson Festival of Books

The Tucson Festival of Books takes no steps to verify, determine or otherwise confirm the race, ethnicity and or lineage of its authors, presenters or participants. All claims about history and ancestry of each person participating in the festival are entirely their own. Furthermore, the festival will not deny a qualified author admittance to the festival based on race, color, religion, sex (including pregnancy), national origin, age, disability, veteran status, sexual orientation, gender identity, or genetic information. We follow the University of Arizona’s Nondiscrimination and Anti-harassment Policy which can be accessed here.

American Indian Studies is committed to the highest standards of professional and scholarly conduct and the best ideals of academic freedom. We are also committed to developing strong and sustaining partnerships with people and programs in American Indian and Indigenous communities. These commitments will sometimes create tensions and might at times be in conflict, but we see them both as necessary to our conception of the work we do. Free academic inquiry helps us to test the limits of accepted wisdom, seek out new approaches to chronic problems, and recognize that being creative about the future might lead us to embrace people and ideas that have been in various ways excluded from the American Indian social and political world. At the same time, our commitment to partnering with people and programs in Native communities creates a need for us to make our work intelligible to a constitutive audience of that work. While we retain responsibility for defining the boundaries and limits of our scholarly and creative work, we also actively seek opportunities to be transparent in articulating what we do and why.

In such articulation, we recognize the importance of being able to identify ourselves clearly and unambiguously. Too often, we realize, American Indian studies as a field of academic inquiry has failed to live up to its potential at least in part because of the presence of scholars who misrepresent themselves and their ties to the Native world. While we do not in any way want to suggest that only Native scholars can do good scholarship in Native studies, neither do we want to make light of the importance of scholars who work in this field being able to speak with clarity about who they are and what brings them to their scholarship and creative activity. Indeed, we hope that our partners will subject us to whatever level of scrutiny they find appropriate as we seek to build bridges between the academic world and Indigenous communities.

[Adopted by American Indian Studies faculty, September 2010]

We respectfully acknowledge the University of Arizona is on the land and territories of Indigenous peoples. Today, Arizona is home to 22 federally recognized tribes, with Tucson being home to the O’odham and the Yaqui. Committed to diversity and inclusion, the University strives to build sustainable relationships with sovereign Native Nations and Indigenous communities through education offerings, partnerships, and community service.

Friday, February 24, 2023

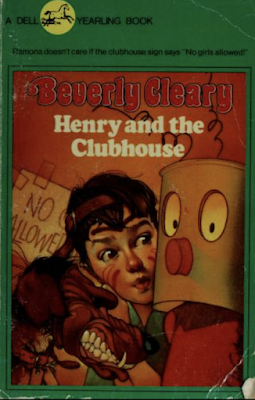

Stereotypes in Beverly Cleary's HENRY HUGGINS

In September he had been Second Indian in a play for the Westward Expansion Unit. That hadn't been too bad. He had stuck an old feather out of a duster in his hair and worn an auto robe his mother let him take to school. It was an easy part, because all he had to say was "Ugh!" First Indian and Third Indian also said "Ugh!" It really hadn't mattered which Indian said "Ugh!" Once all three said it at the same time.

Saturday, February 18, 2023

Not Recommended: The Little Indian Runner

Thursday, February 09, 2023

Highly Recommended: POWWOW DAY by Traci Sorell

Today is powwow day. Then River remembers: no dancing for her this year. Even though she's feeling better lately, she's still not strong enough. Maybe she can at least dance Grand Entry? Join River and her family as they enjoy a cultural tradition -- their tribal powwow. As River tries to make peace with her temporary limitations, she reminds herself that her beloved jingle dress dance is to honor the Creator, the ancestors, and everyone's health -- including her own.

Wednesday, January 18, 2023

Use/Misuse of the Word "Treaty" or "treaty" in Children's Books

On page nine, we see:

Since the last treaty with the tribes, there had not been an attack reported anywhere in this part of Maine. Still, one could not entirely forget all those horrid tales.

The book is set in the 1768; I will try to figure out what treaty the author is having the white character refer to. Obviously the second sentence about "horrid" tales is meant to tell us that white people were being viciously attacked by Native people. There's bias in that passage but use of "treaty" is ok.

The next use is not.

"Good," he grunted. "Saknis make treaty.""A treaty?" Matt was even more puzzled."Nkweniss hunt. Bring white boy bird and rabbit. White boy teach Attean white man's signs."You mean--I should teach him to read?""Good. White boy teach Attean what book say."

It reminded me of the way that Stephanie Meyer used it in her Twilight series. She has a treaty between vampires and a pack of wolves. She misused it, too.

- Belin, Esther, Jeff Berglund, and Connie A. Jacobs. The Dine Reader. Published in 2021 by the Arizona Board of Regents.

- Boulley, Angeline. Firekeeper's Daughter. Published in 2021 by Henry Holt.

- Collins, Suzanne. The Hunger Games. Published in 2008 by Scholastic Press.

- Craft, Aimée. Treaty Words: For As Long As the Rivers Flow. Published in 2021 by Annick Press.

- Crawford, Kelly. Dakota Talks About Treaties. Published in 2017 by Union of Ontario Indians.

- Cutright, Patricia J. Native Women Changing Their World. Published in 2021 by 7th Generation.

- Davids, Sharice. Sharice's Big Voice: A Native Kid Becomes a Congresswoman. Published in 2021 by HarperCollins.

- Davis, L. M. Interlopers: A Shifters Novel. Published in 2010 by Lynberry Press.

- Day, Christine. I Can Make This Promise. Published in 2019 by HarperCollins.

- Dimaline, Cherie. The Marrow Thieves. Published in 2017 by Dancing Cat Books.

- Frank, Anne. The Diary of a Young Girl. Published in the US in 1952 by Doubleday.

- Gansworth, Eric. If I Ever Get Out of Here. Published in 2013 by Scholastic.

- Gansworth, Eric. Give Me Some Truth. Published in 2018 by Scholastic.

- Gansworth, Eric. Apple Skin to the Core. Published in 2020 by Levine Querido

- Gansworth, Eric. My Good Man. Published in 2022 by Levine Querido.

- General, Sara and Alyssa General. Treaty Baby. Published in 2016 by Spirit and Intent.

- George, Jean Craighead. The Buffalo Are Back. Published in 2010 by Dutton.

- Keith, Harold. Rifles for Watie. Published in 1957 by Harper.

- Marshall, Joseph III. In the Footsteps of Crazy Horse. Published in 2015 by Amulet.

- McManis, Charlene Willing. Indian No More. Published in 2019 by Lee & Low Books.

- Merrill, Jean. The Pushcart War.

- Pierce, Tamora. Alanna, the First Adventure; Wild Magic, First Test, Trickster's Choice.

- Prendergast, Gabrielle. Cold Falling White.

- Prendergast, Gabrielle. The Crosswood.

- Sorrell, Traci. We Are Still Here. Published in 2022 by Charlesbridge.

- Speare, Elizabeth George. The Sign of the Beaver. Published in 1983 by Houghton Mifflin.

- Stevenson, Robert Louis. Treasure Island. Published in 1883 by Cassell and Company.

- Tingle, Tim. How I Became A Ghost. Published in 2013 by Roadrunner Press.

- Treuer, Anton. Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask: Young Readers Edition. Published in 2021 by Levine Querido.

- Twain, Mark. The Adventures of Tom Sawyer. Published in 1876 by American Publishing Co.

- Verne, Jules. Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Originally published as a serial in 1870 in France.

- Wilder, Laura Ingalls. Little House on the Prairie. Published in 1935 by Harper (Harper Collins).

Tuesday, January 17, 2023

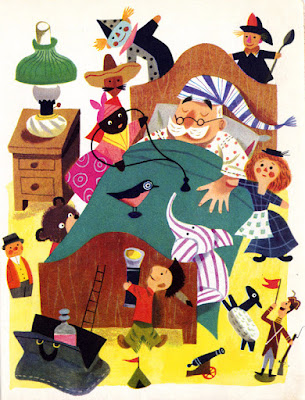

Nostalgia for Margaret Wise Brown's DOCTOR SQUASH THE DOLL DOCTOR

K-Gr 3–This newly illustrated reissue of a 1952 Golden Book recounts the illnesses of various dolls–squeaky soldier, teddy bear with a bloody nose, fireman with a broken leg, Indian with poison ivy, etc–and Doctor Squash, who comes running to dispense medicine and advice as needed. When the good doctor falls ill, the toys get the chance to return the favor and take care of him. Hitch's cartoon illustrations complement the text well with bright colors and great facial expressions. They are updated from the original (no Mammy doll) but still have an old-fashioned look. References to the snowman doll's illness and “wild Indian” have been removed. Perplexingly, the story does continue to refer to cough drops as “good as candy and just as pretty” and to mention writing prescriptions for measles, mumps, chicken pox, and whooping cough. Updated, but still a bit out-of-date.–Catherine Callegari, Gay-Kimball Library, Troy, NH. (c) Copyright 2010. Library Journals LLC, a wholly owned subsidiary of Media Source, Inc. No redistribution permitted. --This text refers to the library edition.

A Little Golden Book first published in 1952 with illustrations by J.P. Miller sees new life with new art, proving yet again that Brown is synonymous with timelessness. When dolls are sick or in pain, there’s really only one doctor to call: the good Doctor Squash, who attends to their every need. From broken legs and poison ivy to coughs and the mumps, the doctor always has the right cure on hand. And when the doc falls ill, the dolls take care of him in return. Some of the original text has been updated to suit the times (for example, the Wild Indian Doll becomes simply the Indian Doll). Gone too are such anachronistic images as the mammy doll. Appropriate though these changes may be, it is a pity that there is no mention of them in this new edition. Nevertheless, playing doctor with dolls never falls out of style, and Hitch’s retro style and modern toy updates work overtime to ensure that this book becomes a classic all over again. Entertaining and charming. (Picture book. 4-8)

The "Indian" doesn't have a big nose, feather and tomahawk in the updated version. I suppose Hitch and the art director at Random House thought that was a good change, but it isn't. Not really. We still have use of a single image to represent "Indian" as though we're all the same. And I suppose they decided it is not ok to have a Black or Latinx doll -- that perhaps they can't be playthings, but did they decide a toy Indian is ok? I think they did. They are wrong, of course. They seem more knowledgeable than the people on FB who feel warmly towards the original, but the "Entertaining and charming" line from the reviewer at Kirkus is disappointing. Overall, from the readers on a FB group page to the professional reviewers, we see lot of room for growth.

Friday, January 13, 2023

"Tlingit don't exist for the benefit of bad teenagers."

Tlingit don't exist for the benefit of bad teenagers.

Sorry I seem to be late to this party. I've known about Touching Spirit Bear for years, but have avoided reading it, until just this week. I'd read about it here, and in Clare Bradford's essay, and figured that I would not like it. Now I have read it, and I do not like it. The book bothered me. Many of the comments here bother me. Some who defend the book use the argument that reading it is helpful for many troubled young readers, so any minor factual inaccuracies don't matter. There seems to be some formula that can be used to balance the benefits against the harms; I don't know what that formula is. The harms do seem to be undervalued by those who make the argument. I have to ask: if thousands of sports fans are made happy by acting out an ugly caricature, does that joy outweigh the tragedy of dehumanizing whole groups of people? How many happy fans balance one young suicide? What exactly is the Stereotype to Redemption exchange rate--and is it a fair transaction?

I am fairly certain that I am not the only Tlingit person who has been informed, as soon as his tribal affiliation is discovered, that "Ooh! I loved Touching Spirit Bear." This has happened to me, more than once, if not in these exact words. That it is intended as a positive statement does not erase the realization that a whole culture is reduced to a couple of characters. (And worse, that these are characters whose creator claims that their culture is not relevant to the important matter of his book.) One wonders how many young readers (or adult readers--many of them teachers, apparently) put down this book, fiction or not, believing that at.oow is kind of like Linus Van Pelt's comic-strip blanket, or that Tlingit villagers can cure a sociopath by letting him dance out his feelings after dinner.

The book may indeed be helpful for some troubled youth. I can't say, but I don't like the cost. Touching Spirit Bear would have been better if the whole Tlingit angle had been left out. The character of Edwin, the Tlingit elder, was more Hippie than Tlingit. Garvey, the parole officer, could have been anyone from Southeast Alaska. Rosey, the Tlingit nurse, was believable, as were the teenagers who carried the stretcher: they would have been acceptable as irrelevant Indians. I read that the author claimed that Touching Spirit Bear was not based on the controversial real-life Tlingit banishment case that hit the national news a few years before his book; neither have I seen any mention of the real-life Circle Peacemaking Program in the Tlingit village of Kake (rhymes with Drake): so it must be assumed that the Tlingit connection in Touching Spirit Bear is mere New-Age appropriative garbage.

Wednesday, January 11, 2023

Back Matter in 2022 book from Charlesbridge -- THE GARDENER OF ALCATRAZ

When Elliott Michener was locked away in Alcatraz for counterfeiting, he was determined to defy the odds and bust out. But when he got a job tending the prison garden, a funny thing happened. He found new interests and skills--and a sense of dignity and fulfillment. Elliott transformed Alcatraz Island, and the island transformed him.

Told with empathy and a storyteller's flair, Elliott's story is funny, touching, and unexpectedly relevant. Back matter about the history of Alcatraz and the US prison system today invites meaningful discussion.

- In the Time Line is "1969-70: Native American occupation of Alcatraz" (p. 36).

- In Alcatraz and Its Gardens (p. 37), there are several subsections:

The first paragraph of "The Early Years" says "Because there was no source of water, Native people did not live on the island (although historians believe the members of the Ohlone tribe may have hidden there to avoid being captured and forced into slavery in the California Mission system)."

The second paragraph says "Native Americans were also imprisoned there for refusing to allow their children to be taken away and placed in boarding schools."

There's an entire subsection called "The Native Occupation." The first paragraph is about the prison being expensive to maintain, and so it was shut down. The second paragraph is:

Then, in 1979, a group of Native activists from different tribes occupied Alcatraz. Their goal was to raise awareness about the brutal ways in which Native people had been treated and to protest the recent closings of reservations across the country. The Indians of All Tribes occupied Alcatraz for nineteen months before the government evicted them. Signs of their presence remain on the island to this day, inspiring visitors to reflect upon Indigenous people's ongoing fight for their rights.

I wish the author had included sources or books for this information. There's a selected bibliography but none of the primary sources, books, online resources, or DVD's that they list are specific to Native people at Alcatraz. She cites books that are not ones for children. For example, she cites Michael Esslinger's Alcatraz: A History of the Penitentiary Years. She could have cited one of Adam Fortunate Eagle's books. You can read his Heart of the Rock: The Indian Invasion of Alcatraz at the Internet Archive (or get a copy from your library). Another option is Troy Johnson's books about the occupation. They are primarily photo records of that period and I find them gripping. The National Park Service hosts a page he wrote about the occupation: We Hold the Rock. She includes links to online resources and could have added ones about the Hopi parents who were imprisoned there. The National Park Service has this one: Hopi Prisoners on the Rock.

- In Author's Note, Smith writes that Corrina Gould, Tribal Chair of the Confederated Villages of Lisjan, "went over the passages concerning Native people's relationship with Alcatraz." (p. 40).

Saturday, December 31, 2022

Highly Recommended: Two for 2022 from Highwater Press!

Highwater Press often sets a high bar for Indigenous-centric publishing. This post recommends two of their 2022 releases: Returning to the Yakoun River and Dancing with Our Ancestors. Both are by Sara Florence Davidson and her father, Robert Davidson, illustrated by Janine Gibbons. Dancing with Our Ancestors is among the Globe & Mail's top-10 children's book for 2022. Both are on AICL's list of the best books we read in 2022, and here's a "short and sweet" summary of why.

Reason #1 to recommend these two books: Emphasis on Indigenous pedagogies

Both offer a close "insider perspective" on two traditions of Haida communities -- fish camp (Returning to the Yakoun River) and potlatch (Dancing with Our Ancestors). The text and the illustrations work together to portray intergenerational Indigenous teaching and learning.

Reason #2: The story-telling

Both are based on the authors' experiences. The writing is clear and straightforward, yet effective at conveying both informative and emotional content. See, for example, Sara Davidson's closing words in Dancing about her brother, or the descriptions of the children's fish camp experience in Yakoun River. I couldn't help but smile at their pleasure over breakfast of "tiny boxes of cereal that we are never allowed to eat at home" and their dash to climb into a little boat so they can ride the wake of a passing motorboat.

Janine Gibbons' illustrations are powerful, and play a key part in the storytelling -- for example, in Returning, you'll see panoramic scenes (such as the end papers), extreme close-ups (such as a cereal bowl, a salmon head seeming to threaten a finger) and more, not just matching but accentuating portions of the text.

Reason #3: The supplemental information

In the back of each book is a map of Haida Gwaii, where the action in the books takes place, as well as some information about the Davidson family.

Take a look at this video on the Portage and Main Web site (less than 30 minutes long) about the potlatch on which Dancing with Our Ancestors is based.

The archived virtual book launch for both books is available for viewing, and is full of interesting information.

Highwater Press sells a teacher's guide to go with the Sk'a'da Stories, and there's a link to a free pronunciation guide to the Haida words that appear in the books.

Reason #4 to recommend these two books: They're part of a strong series.

The two previous Sk'a'da Stories, Jigging for Halibut with Tsinii and Learning to Carve Argillite, created by the same author/illustrator team, were among CBC Books' Best Children's Books of 2021. Throughout the series, they interweave cultural and historical information with storytelling about their family and community. The information goes beyond the basic "Here's what our tradition looks like", in line with an essential purpose of the series -- to actively preserve Haida culture for future generations:

As I watch from the side, I think about the laws that tried to stop us from gathering .... They wanted to stop us from being Haida. No laws stop us today. Today our history is recorded in our art, our stories, our dances, and our songs. Today we dance with our children so our culture cannot be stolen again."

In short, Dancing with OurAncestors and Returning to the Yakoun River are two books to learn from and to appreciate for storytelling and for the Indigenous knowledge shared.

Monday, December 12, 2022

AICL's Year In Review for 2022

"We" at AICL is two people: Debbie Reese and Jean Mendoza. AICL is not an association or an organization or an employer of any sort. It is a blog Debbie founded in 2006. In 2016, she invited Jean to join her as co-editor. We are two people with lived experience, knowledge, and expertise who study and write about depictions of Native peoples in children's books.

The care we take, we think, is why AICL has a high profile as a reliable source of information. Our work helps educators, librarians, parents, professors, and editors at publishing companies. Our annual lists are not comprehensive. We can’t read every book in the year of its publication.

This year’s list is different.

This year, we are departing from our goal of populating the annual Best Books list with recommended books published in that year. With the 2022 list, we will be listing books we recommend that were published in any year. Here’s why: these past few years have held challenges for both of us -- some of them positive! -- that have made it difficult for us to keep up with the new books coming out. We have some catching up to do. "So many new books by Native creators" is a good problem to have! We're so pleased by that development. In 2021, for example, we were unable to review Adrienne Keene's Notable Native People, but we did recommend it this year once we got a copy. And, one of our favorite books, Where Did You Get Your Moccasins, by Bernelda Wheeler, came out before we started doing annual Best Books lists. Wheeler’s book initially came out in 1986, and was reissued as an e-book in 2019.

You will see both of those books on this year’s list.

A word about the knowledge and lived experience we bring to our reading of books with Native content: there’s always something to learn. For example, we’ve changed how we alphabetize author/illustrator names in Indigenous languages, thanks to correspondence with a writer. That writer is Hetxw’ms Gyetxw. His English name is Brett D. Huson. We’ve included several of his books on our Best Books lists. Recently, he let us know that, for alphabetizing purposes, the usual “Surname comma First Name” does not work for the Gitxsan name. So on this year’s Best Books list, we use the Gitxsan name without treating the second word as a surname. And we put his English name after his Gitxsan name.

Finally, we want you to use books we recommend all year! Of course, you can use them during Native American Heritage Month but Native children are Native all year round, and they should see themselves in books, all year round. (And November’s not the only time non-Native children should see accurate, positive images of Native people, either!) If you’re doing a classroom lesson or library programming on Native women in politics, include Deb Haaland: First Native American Cabinet Secretary by Doerfler and Martinez and She Persisted: Wilma Mankiller by Traci Sorell. Make room in your science curriculum for books like The Raven Mother by Hetx’wms Gyetxw (Brett D. Huson). Have students in art classes do illustrator studies of award winners Michaela Goade or Julie Flett. Most libraries have many patrons that come in for mysteries. Tell them about Sinister Graves: A Cash Blackbear Mystery by Marcie Rendon.

We also hope AICL’s lists of recommended reading will inspire you to choose great books by Native creators as gifts during the holiday season, or any time.

– Debbie and Jean