Note from Debbie on Nov 20 at 7:30 AM: This "Dear Michael" post is now a conversation between myself and Michael Grant. Here's a Table of Contents. Michael Grant's is submitting his comments/responses to me by email.

November 17: Debbie's letter to Michael about GONE

November 18: Michael's response (submitted by email on Nov 18)

November 19: Debbie's response

November 20: Michael's response (submitted by email on Nov 19)

November 20: Debbie's response (about erasure)

November 21:

Debbie's response (Lana's identity)

November 22: Debbie's note to Michael on dialog

__________

November 17, 2016

Dear Michael Grant,

Our conversation yesterday at Jason Low's opinion piece for School Library Journal didn't go well, did it? I entered it, annoyed at what you said last year in your "On Diversity" post. There, you said:

Let me put this right up front: there is no YA or middle grade author of any gender, or of any race, who has put more diversity into more books than me. Period.

Then you had a list where you were more specific about that diversity. Of Native characters, you said:

Native American main character? No. Australian aboriginal main character, but not a Native American. Hmmm.

You do, in fact, have a Native character in Gone. I'd read it but didn't write about it. So when you commented to Jason in the way that you did, I responded as I did, saying you'd erased a Native character right away in one of your books. With that in mind, and your claim that you've done more than anyone regarding diversity, I said you're part of the problem. You wanted to know what book I was talking about. Indeed, you were quite irate in your demands that I name it. You offered to donate $1000 to a charity of my choice if I could name the book. You seemed to think I could not, and that I was slandering you.

In that long thread, I eventually named the book but you said I was wrong in what I'd said. So, here's a review. I hope it helps you see what I meant, but based on all that I've seen thus far, I'm doubtful.

Here's a description of the book:

In the blink of an eye, everyone disappears. Gone. Except for the young. There are teens, but not one single adult. Just as suddenly, there are no phones, no internet, no television. No way to get help. And no way to figure out what's happened. Hunger threatens. Bullies rule. A sinister creature lurks. Animals are mutating. And the teens themselves are changing, developing new talents—unimaginable, dangerous, deadly powers—that grow stronger by the day. It's a terrifying new world. Sides are being chosen, a fight is shaping up. Townies against rich kids. Bullies against the weak. Powerful against powerless. And time is running out: on your birthday, you disappear just like everyone else. . . .

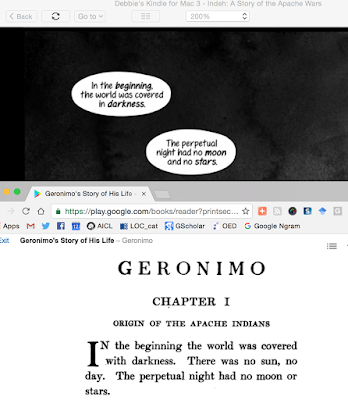

Chapter one is set at a school in California. It opens with a character named Sam, who is listening to his teacher talk about the Civil War. Suddenly the teacher is gone. It seems funny at first but then they realize that other teachers are gone, and so is everyone who is 15 years old, or older. In chapter two, Sam, his friend Quinn, and Astrid (she's introduced in chapter one as a smart girl) head home, sure they'll find their parents. They don't.

Partway through chapter two, you introduce us to Lana Arwen Lazar, who is riding in a truck that is being driven by her, grandfather, Grandpa Luke, who is described as follows (p. 19-20):

He was old, Grandpa Luke. Lots of kids had kind of young grandparents. In fact, Lana’s other grandparents, her Las Vegas grandparents, were much younger. But Grandpa Luke was old in that wrinkled-up-leather kind of way. His face and hands were dark brown, partly from the sun, partly because he was Chumash Indian.

At first, I thought, "cool." You were bringing a tribally specific character into the story! If he's Chumash, then, Lana is, too! There's whole chapters about her. She's a main character. But, you didn't remember her. Or maybe, in your responses at SLJ, you were too irate to remember her?

Anyway, I wasn't keen on the "wrinkled-up-leather" and "dark brown" skin because you're replicating stereotypical ideas about what Native people look like.

As I continued reading, however, it was clear to me that you were just using the Chumash as decoration. You clearly did some research, though. You've got Grandpa Luke, for example, pointing with his chin. Thing is: I've been seeing that a lot. It makes me wonder if white people have a checklist for a Native character that says "make sure the character points with the chin rather than fingers."

Back to chapter two... Grandpa Luke pointed (with his chin) to a hill. Lana tells him she saw a coyote there and he tells her not to worry (p. 20):

“Coyote’s harmless. Mostly. Old brother coyote’s too smart to go messing with humans.” He pronounced coyote “kie-oat.”

Hmmm... Grandpa Luke... teaching Lana about coyote? That sounds a bit... like the chin thing. I'm seeing lot of stories where writers drop in coyote. Is that on a check list, too?

Next, we learn that Lana is with her grandpa because her dad caught her sneaking vodka out of their house to give it to another kid named Tony. Lana defends what she did, saying that Tony would have used a fake ID and that he might have gotten into trouble. Her grandpa says (p. 21):

“No maybe about it. Fifteen-year-old boy drinking booze, he’s going to find trouble. I started drinking when I was your age, fourteen. Thirty years of my life I wasted on the bottle. Sober now for thirty-one years, six months, five days, thank God above and your grandmother, rest her soul.”

Oh-oh. Alcohol? That must be on the checklist, too. I've seen a lot of books wherein a Native character is alcoholic.

Lana teases her grandpa, he laughs, and then the truck veers off the road and crashes. Grandpa Luke is gone. Just like the other adults. Lana lies in the truck, injured. Her dog, Patrick, is with her. The chapter ends and you spend time with the other characters.

His being gone is what I was referring to when I said that you erased him. At SLJ, you strongly objected to me saying that. You interpreted that as me saying you're anti-Native. You said that "every adult is disappeared." That you did that to "African-Americans, Polish-Americans, Mexican-Americans, Norwegian-Americans, French-Americans, Italian-Americans..." Yes. They all go away in your story, and because they do, you think it is wrong for me to object. That's when I said to you that you're clearly not reading any of the many writings about depictions of Native people. It just isn't ok to create Native characters and then get rid of them like that. Later in the SLJ thread, you said:

"I threw the reference to the Chumash in as an effort to at least acknowledge that there are still Native Americans in SoCal. That was it. It's a throwaway character we see for three pages out of a 1500 page series."

Really, Michael? That's pretty awful. I hope someone amongst your writing friends can help you see why that doesn't work!

Lana is back in chapter seven. A mountain lion appears. Patrick fights it and it takes off, but Patrick has a bad wound. Lana drifts off to sleep again, holding Patrick's wound to stop the blood. She wakes, part way through chapter ten. Patrick isn't with her but comes bounding over, all healed! Lana wonders if she had healed him. She glances at her mangled arm, which is now getting infected. She touches it, drifts off, and when she wakes it, too is healed. Next she heals her broken leg. All better, she stands up.

So---Lana is a healer, Michael? That, too, is over in checklist land (Native characters who heal others).

In chapter fifteen, Lana and Patrick set out to find food and water and hopefully, her grandfather's ranch. After several hours of walking in the heat, they find the wall that is an important feature of the story, and then, a patch of green grass. There's a water hose and a small cabin. They drink, and she washes the dried blood off her face and hair.

In chapter eighteen, Lana wakes in the cabin, and remembers the last few weeks. She remembers putting the bottle of vodka in a bag with "the beadwork she liked" (p. 203). My guess, given that her grandfather is Chumash, is that the bag we're meant to imagine is one with Native beadwork designs on it.

Lana hears scratching at the door, like the way a dog scratches at a door, and she hears a whispered "Come out." Oh-oh (again), Michael! Native people who can communicate with animals! That on the checklist, too? Patrick's hackles are raised, his fur bristles. They finally open the door and go out out but don't see anyone. She uses the bathroom in an outhouse. When Lana and Patrick head back to the cabin, a coyote is standing there, between the outhouse and the cabin. This coyote, however, is the size of a wolf. She thinks back on what she learned about coyotes, from Grandpa Luke (p. 207):

“Shoo,” Lana yelled, and waved her hands as her grandfather had taught her to do if she ever came too close to a coyote.

It didn't move, though. Behind it were a few more. Patrick wouldn't attack them, so, Lana yelled and charged right at them. The coyote recoiled in surprise. Lana was a flash of something dark, and the coyote yelped in pain. She made it to the cabin. She heard the coyotes crying in pain and rage. The next day, she found the one who she'd charged at (p. 207):

Still attached to its muzzle was half a snake with a broad, diamond-shaped head. Its body had been chewed in half but not before the venom had flowed into the coyote’s bloodstream.

What does that mean? Does Lana's healing power mean snakes will defend her? Or, that she can summon them to help her? Or is the appearance of these snakes just coincidental and has nothing to do, really, with Lana?

In chapter twenty-five, two days have passed since Lana's encounter with the coyotes. Lana and Patrick eat the food they find in the cabin, and learn that it belonged to a guy named Jim Brown. He has 38 books in the cabin. Lana passes time reading them. At one point, she realizes there's a space underneath the cabin. In it, she finds gold bricks. She remembers the picks and shovels she saw outside, and the tire tracks leading to a ridge and thinks that, perhaps, Jim and his truck are there. She fills a water jug, and the two set off, following the tire tracks.

In chapter twenty-seven, Lana and Patrick reach an abandoned mining town. She look for keys to the truck they find, and, they peek into the mine shaft. Suddenly they hear coyotes. It seems Lana can hear them saying "food." Lana and Patrick enter the mine, but the coyotes don't follow them. Then, one of them talks to her, telling her to leave the mine. They rush in and attack her but then stop, clearly afraid themselves. She's now their prisoner. They nudge her down, deeper into the mine. She senses something there, hears a loud voice, passes out, and wakes, outside.

In chapter twenty nine, the coyotes push her on through the desert. She thinks of the lead coyote as "Pack Leader." He's the one who speaks to her. She asks him why they don't kill her. He says (p. 326):

“The Darkness says no kill,” Pack Leader said in his tortured, high-pitched, inhuman voice.

That "Darkness" is the voice she heard in the mine. It wants her to teach Pack Leader... She asks Pack Leader to take her back to the cabin so she can get human food there. Later on, Darkness speaks through Lara.

Ok--Michael--I've spelled out how your depictions of Lana fail. There's so much stereotyping in there. I gotta take off on a road trip now. I may be back, later, to clarify this letter. I think it is clear but may be missing something in my re-read of it. If you care to respond, please do!

Sincerely,

Debbie Reese

American Indians in Children's Literature

__________

November 18th (Michael Grant's response to Debbie Reese):

Hi, it's Michael Grant.

But feel free to call me Satan.

I'm writing this at Ms. Reese's kind invitation because we've had

a . . . well, a bit of a thing. Which I

think we both find distressing because we are on the same side. So, anyway, I apologize for this being so

long. (Bear in mind I write 500-page

books, so you're getting off easy.)

You know the running gag on The Simpsons where Marge will look at

Homer and ask him what he's thinking?

And then we get a cutaway to a cross-section of Homer's head and see

that inside is a toy monkey banging a tin drum?

That's sort of the level of disconnect we have here.

Basically, what you believe I thought or knew is not even

close. Partly it may be the way I

write. If you had a number line from

seat-of-the-pants writers (pantsers) to planners I would be so far over on the

pantser side there'd be no one to my left.

It's almost all improvised.

So, things you (and probably most people) see as a plan, I know

to be improvised. I write big,

densely-plotted books with big casts and multiple concurrent plot lines. I also write series, and in my approach to a

series, the whole thing is essentially one long book. I like doing this because (among other

reasons) I like plenty of space to play

out character arcs. My series are

'built' like a TV mini-series. I know

that's not indicated in any way on the book, but I don't design the covers.

So the little toy monkey in my head is worrying from Page 1 about

the plot primarily. Not that it's the

only thing, it's just the hardest thing, so most of my thinking is on

that. Second comes character.

As I always tell aspiring writers, there's no 'right' way to do

this job. There's only your way, which

is whatever it takes to get you from Page 1 to the little hash marks at the

end. But civilians - people who are not

writers - are told a lot of nonsense by writers trying, usually unsuccessfully,

to explain how we do what we do. The

true answer is: we don't know. But

that's unsatisfying, so we make up a bunch of reasonable-sounding nonsense, and

civilians come away with all these notions of inspiration and falling in love

with your characters and tearing your soul open (which sounds painful) and they

think it's real. It's mostly not. Writing is not inspiration so much as

problem-solving. (And typing.) A series

of if-then propositions. Constant

reliance on imagination, over which I, at least, have very little conscious

control.

You need to understand that whatever image we put out there, we

are scared little children trying to cajole the mute beast in the back of our

heads into giving us the ideas we then type up.

I'm not complaining - it's the best gig in the world. I have a ridiculously great life. (Now.) I've done real work, I've been poor, I

know and remember and thank the universe daily for giving me this, instead of

what I started out with. So, not

complaining; explaining. But an

overwhelming amount of our mental resources is spent convincing ourselves that

we are doing something real. That we

aren't just delusional. Yes, I should be

over that. But I'm not. I don't know a writer who is.

So, with that aside, I'm going to respond with some specifics re:

Gone. Here's your review and my notes.

Not sure how the layout will work...let's see [note from Debbie: Grant copied portions of my review and followed the copied parts with his comments, in bold. For everyone's convenience, I'm inserting my initials in front of the copied portions.]:

DR: Chapter one is set at a school in California. It opens with a

character named Sam, who is listening to his teacher talk about the Civil War.

Suddenly the teacher is gone. It seems funny at first but then they realize

that other teachers are gone, and so is everyone who is 15 years old, or older.

In chapter two, Sam, his friend Quinn, and Astrid (she's introduced in chapter

one as a smart girl) head home, sure they'll find their parents. They don't.

Partway through chapter two, you introduce us to Lana Arwen

Lazar, who is riding in a truck that is being driven by her, grandfather,

Grandpa Luke, who is described as follows (p. 19-20):

He was old, Grandpa Luke. Lots of kids had kind of young

grandparents. In fact, Lana’s other grandparents, her Las Vegas grandparents,

were much younger. But Grandpa Luke was old in that wrinkled-up-leather kind of

way. His face and hands were dark brown, partly from the sun, partly because he

was Chumash Indian.

At first, I thought, "cool." You were bringing a

tribally specific character into the story! If he's Chumash, then, Lana is,

too! There's whole chapters about her. She's a main character. But, you didn't

remember her. Or maybe, in your responses at SLJ, you were too irate to

remember her?

MG: I'm author or

co-author of, give-or-take, 150 books, 13 series, over 27 years. Ballpark, that's, say, 30,000 pages. Probably, what, 1000 named characters? Probably more, I have no way to add it up.

Deb, I have forgotten entire series, let alone

characters. I could not name the main

characters in Everworld, for example, or Remnants. You know why I always say something vague

like "it's around 150 books?"

Because every time I count it comes out different. I have frequently

forgotten that I am the author of the Barf-O-Rama series. Okay, maybe forgetting that is deliberate,

but I actually loved Magnificent 12, and with a gun to my head I couldn't tell

you a third of the characters.

I'd be concerned it's old age, but my memory has never been good

for those kinds of things. Don't take my

word for it, ask anyone who knows me in kidlit.

Quick story: I used to wait

tables and was damn good at it, too, but only because I was organized. People skills? Well, I waited on this couple, chatted, got

to be friendly, they paid and left. I went

to the front to seat a couple I saw there.

Same people. I did not recognize

them.

So, TL;DR: forgetting the background of one out of at least 1000

characters? Not only possible,

inevitable.

DR: Anyway, I wasn't keen on the "wrinkled-up-leather" and

"dark brown" skin because you're replicating stereotypical ideas

about what Native people look like.

MG: Actually, I

was thinking Native Americans are darker-skinned on average than white folks,

but mostly I was thinking: old dude who lives in the desert.

DR: As I continued reading, however, it was clear to me that you were

just using the Chumash as decoration. You clearly did some research, though.

You've got Grandpa Luke, for example, pointing with his chin. Thing is: I've

been seeing that a lot. It makes me wonder if white people have a checklist for

a Native character that says "make sure the character points with the chin

rather than fingers."

MG: You know when I first learned about the pointing

thing? Just now, reading your note. I had literally no idea. He points with his chin because he's

driving.

DR: Back to chapter two... Grandpa Luke pointed (with his chin) to a

hill. Lana tells him she saw a coyote there and he tells her not to worry (p.

20):

“Coyote’s harmless. Mostly. Old brother coyote’s too smart to go

messing with humans.” He pronounced coyote “kie-oat.”

Hmmm... Grandpa Luke... teaching Lana about coyote? That sounds a

bit... like the chin thing. I'm seeing lot of stories where writers drop in

coyote. Is that on a check list, too?

MG: Sorry,

nope. Everyone hears the coyotes because

they've mutated. (Incidentally, not my

best choice for the book, but, live and learn.)

The coyotes are there because they are typical large fauna in the SoCal

desert. (And sometimes here in Tiburon

at night.) Basically I had to decide

whether the mutagenic effect of the FAYZ worked on animals as well as humans,

and I thought this might be fun.

DR: Next, we learn that Lana is with her grandpa because her dad

caught her sneaking vodka out of their house to give it to another kid named

Tony. Lana defends what she did, saying that Tony would have used a fake ID and

that he might have gotten into trouble. Her grandpa says (p. 21):

“No maybe about it. Fifteen-year-old boy drinking booze, he’s going

to find trouble. I started drinking when I was your age, fourteen. Thirty years

of my life I wasted on the bottle. Sober now for thirty-one years, six months,

five days, thank God above and your grandmother, rest her soul.”

Oh-oh. Alcohol? That must be on the checklist, too. I've seen a

lot of books wherein a Native character is alcoholic.

MG: My best friend at the time (that's over) is a

recovering alcoholic. My father-in-law

is a recovering alcoholic. (Loooong time

sober.) It was in my head. Luke

is an alcoholic to signal that maybe Lana has a genetic predisposition, and to

explain why Luke is upset with Lana. Am

I aware that alcoholism rates are high on Native American reservations? Of course.

Can I see where you'd think that's where I was going? Yes, I do.

Here's the thing: had I consciously thought Indian=Alcoholic, the scene

would have been different. Why? Because it would be a trope, and I don't like

writing clichés.In effect

he's only an alcoholic because I need him to bitch at Lana.

DR: Lana teases her grandpa, he laughs, and then the truck veers off

the road and crashes. Grandpa Luke is gone. Just like the other adults. Lana

lies in the truck, injured. Her dog, Patrick, is with her. The chapter ends and

you spend time with the other characters.

His being gone is what I was referring to when I said that you

erased him. At SLJ, you strongly objected to me saying that. You interpreted

that as me saying you're anti-Native. You said that "every adult is

disappeared." That you did that to "African-Americans,

Polish-Americans, Mexican-Americans, Norwegian-Americans, French-Americans,

Italian-Americans..." Yes. They all go away in your story, and because

they do, you think it is wrong for me to object. That's when I said to you that

you're clearly not reading any of the many writings about depictions of Native

people. It just isn't ok to create Native characters and then get rid of them

like that. Later in the SLJ thread, you said:

"I threw the reference to the Chumash in as an effort to at

least acknowledge that there are still Native Americans in SoCal. That was it.

It's a throwaway character we see for three pages out of a 1500 page

series."

Really, Michael? That's pretty awful. I hope someone amongst your

writing friends can help you see why that doesn't work!

MG: My

characters are my employees. They aren't

my pals, they work for me. Anyone who

comes to work for me has to be ready for the fact that I do have rather a

tendency to kill characters: to 'fire' them.

With extreme prejudice. (It's

worse than a 'you're fired!' from Trump.

But not as bad as having him grab you by the. . .) So, the way this works is if you go to work

for Michael Grant (me), you're quite likely to end up dead. Now, if I can only kill white people, I think

the EEOC is going to have a beef with me.

Put another way, if I can't kill a diverse character, I can't hire a

diverse character. It's a basic part of

the job description: Michael's a good

boss. . . except if he kills you. That's the nature of the gig.

DR: Lana is back in chapter seven. A mountain lion appears. Patrick

fights it and it takes off, but Patrick has a bad wound. Lana drifts off to

sleep again, holding Patrick's wound to stop the blood. She wakes, part way

through chapter ten. Patrick isn't with her but comes bounding over, all

healed! Lana wonders if she had healed him. She glances at her mangled arm,

which is now getting infected. She touches it, drifts off, and when she wakes

it, too is healed. Next she heals her broken leg. All better, she stands up.

So---Lana is a healer, Michael? That, too, is over in checklist

land (Native characters who heal others).

MG: Lana was

never a Native-American in my head. In

my head, she's basically Latina. (The 2 Vegas grandparents) When I came up with the name

"Lazar" it was meant to be a riff on Lazarus that would still sound

Hispanic. Her middle name is Elvish.

(Arwen Evenstar, LOTR) Both together

were meant to sort of point to 'healing.'

She's a healer because I needed a healer. I couldn't have all this violence going on

without some method of repairing people and getting them back in the

action. It had literally nothing to do

with her ethnicity, at least in my head.

And again, had I thought I was doing that, I'd have done something

different because it would have been a hoary cliché.

Again, back to my employer/employee relationship: Basically the job description was,

"Troubled tough chick who becomes Healer and will totally still shoot

you." That's what Lana was. I don't

think at any point after that I thought about or referenced her ethnicity. She was not her race, she was her function,

and her specific personality.

DR: In chapter fifteen, Lana and Patrick set out to find food and

water and hopefully, her grandfather's ranch. After several hours of walking in

the heat, they find the wall that is an important feature of the story, and

then, a patch of green grass. There's a water hose and a small cabin. They

drink, and she washes the dried blood off her face and hair.

In chapter eighteen, Lana wakes in the cabin, and remembers the

last few weeks. She remembers putting the bottle of vodka in a bag with

"the beadwork she liked" (p. 203). My guess, given that her

grandfather is Chumash, is that the bag we're meant to imagine is one with

Native beadwork designs on it.

Lana hears scratching at the door, like the way a dog scratches

at a door, and she hears a whispered "Come out." Oh-oh (again),

Michael! Native people who can communicate with animals! That on the checklist,

too? Patrick's hackles are raised, his fur bristles. They finally open the door

and go out out but don't see anyone. She uses the bathroom in an outhouse. When

Lana and Patrick head back to the cabin, a coyote is standing there, between

the outhouse and the cabin. This coyote, however, is the size of a wolf. She

thinks back on what she learned about coyotes, from Grandpa Luke (p. 207):

“Shoo,” Lana yelled, and waved her hands as her grandfather had

taught her to do if she ever came too close to a coyote.

It didn't move, though. Behind it were a few more. Patrick

wouldn't attack them, so, Lana yelled and charged right at them. The coyote

recoiled in surprise. Lana was a flash of something dark, and the coyote yelped

in pain. She made it to the cabin. She heard the coyotes crying in pain and

rage. The next day, she found the one who she'd charged at (p. 207):

Still attached to its muzzle was half a snake with a broad,

diamond-shaped head. Its body had been chewed in half but not before the venom

had flowed into the coyote’s

bloodstream.

What does that mean? Does Lana's healing power mean snakes will

defend her? Or, that she can summon them to help her? Or is the appearance of

these snakes just coincidental and has nothing to do, really, with Lana?

In chapter twenty-five, two days have passed since Lana's

encounter with the coyotes. Lana and Patrick eat the food they find in the

cabin, and learn that it belonged to a guy named Jim Brown. He has 38 books in

the cabin. Lana passes time reading them. At one point, she realizes there's a space

underneath the cabin. In it, she finds gold bricks. She remembers the picks and

shovels she saw outside, and the tire tracks leading to a ridge and thinks

that, perhaps, Jim and his truck are there. She fills a water jug, and the two

set off, following the tire tracks.

In chapter twenty-seven, Lana and Patrick reach an abandoned

mining town. She look for keys to the truck they find, and, they peek into the

mine shaft. Suddenly they hear coyotes. It seems Lana can hear them saying

"food." Lana and Patrick enter the mine, but the coyotes don't follow

them. Then, one of them talks to her, telling her to leave the mine. They rush

in and attack her but then stop, clearly afraid themselves. She's now their

prisoner. They nudge her down, deeper into the mine. She senses something

there, hears a loud voice, passes out, and wakes, outside.

In chapter twenty nine, the coyotes push her on through the

desert. She thinks of the lead coyote as "Pack Leader." He's the one

who speaks to her. She asks him why they don't kill her. He says (p. 326):

“The Darkness says no kill,” Pack Leader said in his tortured,

high-pitched, inhuman voice.

That "Darkness" is the voice she heard in the mine. It

wants her to teach Pack Leader... She

asks Pack Leader to take her back to the cabin so she can get human food there.

Later on, Darkness speaks through Lara.

Ok--Michael--I've spelled out how your depictions of Lana fail.

There's so much stereotyping in there. I gotta take off on a road trip now. I

may be back, later, to clarify this letter. I think it is clear but may be

missing something in my re-read of it. If you care to respond, please do!

MG: The problem again is that we have a

disconnect. In Luke, you're seeing a

Native American. I'm seeing a temp

employee who is there to deliver some character background on Lana and then

conveniently die. Nothing about Lana was

ever Native American in my head; she's a character, there for a reason that has

nothing to do with her background. But

you were seeing something different.

It's a frequent issue in books - what's in your head defines

your read, as what's in my head defines my writing.

So, when I said I didn't recall writing a Native American

character, that's just the truth. Luke

is a throwaway. Like hiring a temp for a

day's work. He's there to deliver a few

lines and poof. Lana's there for a much

bigger role, but one that has nothing to do with her ethnicity. I'm not dismissing ethnicity, but

essentially, we had 332 kids starving and murdering each other, and my focus

was on making it work. The characters

had other stuff on their minds. They

were eating pet cats and being threatened by psychopaths. And I was sweating bullets hoping somehow it

would all come together.

But can I understand how you'd read it and think, "Oh, cool,

a Native American character? Maybe this

will go somewhere?" Sure. Of course, now. But the thought never entered my head

then. I mean, I've hired hundreds,

probably thousands, of throwaway characters, and they've been of all races and

genders, and when they've delivered their lines, they go away. Again: if you can't be killed off, you can't

be hired.

So, let me explain how this looks to me. First, yes, I will claim my diversity

'points,' and proudly. Because however

much it irritates people, the fact is I was pushing diverse casts long before

anyone was scolding me into doing it.

I'm proud of the work I've done.

I believe in the cause, and I'm not going to pretend I didn't write what

I wrote. No one was nagging us to be

inclusive in 1993 when we were writing Ocean City. We (I was writing with Katherine in those

days) did it because we want to have access to any and all interesting

characters. And yes, in part because we

thought it was the 'right thing' to do.

I've continued to keep diverse characters front and center. I didn't have to be pushed into it, it's who

I am. It may be the one thing my mother

got right with me.

But now, let me broaden this out.

I am not fundamentally a literary type (he says, handing a snarky line

to future reviewers); I am, deep down in my soul, political. As you see the world through various prisms,

my prism tends to be politics, philosophy, ethics, all that stuff that doesn't

earn any money. That's my jam: politics.

I get politics at a sort of intuitive level. I feel the flow. You don't have to believe me, you can think

I'm crazy, but politics runs deep with me.

I quit writing for a year to do political ads for the Democratic

Legislative Campaign Committee and won a Pollie Award - 3rd class - for some

piece of whatever. As much as I've

written fiction, I've probably written more on politics. Used to have a politics blog.

The atrocity that is Trumpy the Pig was a knife to the guts. I felt it coming. Did everything I could to stop it. Obviously that didn't work. (Duh.)

But, as an armchair pol, I sensed, intuited, whatever, that something

like this was coming. Before my eldest

went off to college we were talking and I said dude, this is swinging

back. You could feel the pendulum had

reached its limit and was just about to come swinging back. My first instinct is political: you defend what is defensible. In fact, my guide on this is Field Marshall

Montgomery (what?) who was a big believer in 'tidying' the battlefield. In

other words, giving up what can't be held, and strengthening what can be.

What I see is that the Good Guys (us) were not in any way

prepared for what had happened.

Instinctively, I wanted a tidy battlefield. There are things we can defend and win, there

are things we have to defend regardless, and there are things where we should

take a step back, the better to prevail in the end. That was my initial (intemperate) comment on

the SLJ thread. I wasn't taking a shot

at Jason, who my wife tells me (with some force) is a good dude. And again, bear in mind, I don't spend my

days talking about books or libraries, I spend my days arguing politics with

people who all fall into a sort of brutalist 'shop talk' jargon.

Now, here's the thing. I

want more diverse characters and more diverse writers. I think it's a good in itself, and it's more

fun for me as a writer. But if I write a

Native American character and have to worry I'll be beaten up and called names,

I'm not going to do it. No non-Native

American writer will. That is the

opposite of what we both want.

At the same time, I understand that it is galling to see Native Americans

reduced to sideline roles in the country that was stolen from them. Lovely country, sorry about the smallpox and

the massacres, now go stand in the corner, look solemn and say,

"how." A bit like having a

prop Jew in a Holocaust play directed by Germans. Just as I understand how galling it is when

that kind of treatment goes to African-American, gay, Latino, etc...

characters. But given the situation that

exists - mostly white writers - the only way for large numbers of PoC characters to come into existence is for

them to be written by white writers.

Yes, that sucks. Hopefully that

will change. If I had a magic wand and

could make it happen, I'd do it. (Might

cure cancer first.) My tiny contribution

today was to give an African-American starting writer my email and my

lawyer. (And no one gets my email.) But no one can just snap their fingers and

redress the balance tonight. It's going to be a long war of attrition. So for the short term, it's largely going to

be white writers. The question I have

is: how do we get white writers to write

diverse characters?

Not by attacking them when they do. Criticize?

Of course. Comes with the

territory. Teach? Of course.

Review? Yep. Where I part company is the destruction of

books. Mein Kampf is still on the

market, and, as a Jew? I would never

support banning it. I flatly reject the banning or withdrawing of books.

I think we need to find a way forward that squares that

circle. We need a way to do the work of

diversity without the attacks on writers.

And they are attacks. That doesn't mean I think we should be having

writers produce new L'il Black Sambo books, nor does it mean I don't think you

and others should hold our feet to the fire.

But not every infraction is a firing offense.

Writers don't want to be told what to write. Activists don't want us randomly grabbing

stereotypes and plugging them in. This

doesn't feel insoluble to me, if we can start by working working together

toward a goal we share, a goal I've put an awful lot of work into, as have

you.

Damned if I know how we do that, but we all have our skills, and

mine is making stuff up, not bringing people together. Or punctuation. Or driving at the speed

limit. Or not eating an entire pie. So many things I'm not good at. But if

someone has an idea how to bring peace between activists and writers, I'm

open.

Michael Grant

__________

Saturday, November 19: Debbie Reese's response to Michael Grant's email, written as an observation rather than a point-by-point rebuttal:

Grant says that he "improvised" when creating the Native characters and what they do, and that he relied on his imagination. Improvisation and imagination, however, don't come from nowhere. They are infused with ideas about the world that come from ones existence in the world. Grant is able, from his point of view, to wave away all that I pointed out in my review. His unwillingness to acknowledge the ways that he stereotypes Native people is a problem. Obviously, his editors and fans are in that same space. They are not able to see these problems and, subsequently, unable to recognize the harm they do. Collectively, they are perpetuating these stereotypes. Grant does this with other groups, too. See the review of the way he depicted autism, here: Review: the Gone series by Michael Grant and his comment to that review. As I read GONE, I highlighted passages about Petey. I highlighted passages about Edilio, who is called a wetback. And I highlighted the first death in the book (p. 43): "She was black, black by race and from the coating of soot."

Grant thinks I and Corinne Duyvis are wrong to point out these problematic representations in his books. We have a larger challenge, he argues, ahead of us (the president-elect). It seems he wants us to set aside our work as people who speak up to misrepresentations in children's and young adult books. The thing is, Grant's views--and the president-elect's views--were shaped by stories in books, in the media, and by stories told to them by parents, friends and colleagues... That is why Grant's depictions matter.

__________

Sunday, Nov 20, 2016: Michael Grant's response to Debbie Reese (submitted on Nov 19):

MG: And now, continuing the dialog, my response to Ms. Reese's response to my response to. . . wherever we are at this point. (I'll keep this under the character limit. I hope.)

DR: "Grant says that he "improvised" when creating the Native characters and what they do, and that he relied on his imagination. Improvisation and imagination, however, don't come from nowhere. They are infused with ideas about the world that come from ones existence in the world. Grant is able, from his point of view, to wave away all that I pointed out in my review.

MG: No, I responded honestly and at some length. Yes, of course improvisation comes from imagination and background. I'm well aware of the likelihood that much of what I think is correct is not, to one degree or another. I'm telling you where I was at, 10 years ago, when I was writing GONE, as best I can remember. All I can do is tell the truth.

DR: His unwillingness to acknowledge the ways that he stereotypes Native people is a problem.

Obviously, his editors and fans are in that same space. They are not able to see these problems and, subsequently, unable to recognize the harm they do. Collectively, they are perpetuating these stereotypes. Grant does this with other groups, too. See the review of the way he depicted autism, here: Review: the Gone series by Michael Grant and his comment to that review. As I read GONE, I highlighted passages about Petey. I highlighted passages about Edilio, who is called a wetback. And I highlighted the first death in the book (p. 43): "She was black, black by race and from the coating of soot."

The GONE series runs about 3000 pages. Yes, Edilio is called a 'wetback' and other slurs as well. By people we hate. Let me tell you about Edilio, and why that remark, Ms. Reese, is a perfect example of the kind of drive-by book assassination I and 90% of writers find so chilling.

Edilio is an undocumented Honduran. He is introduced at the start as an almost throw-away character. But I knew he wasn't. Over the course of the series he becomes - despite not possessing powers - the most trusted, relied-upon, steady and mature person in the FAYZ, the leader of the FAYZ. I've received probably thousands of notes, tweets, emails, and in-person testimonials from Hispanic and gay kids (Edilio comes out in the series) about the importance to them of Edilio.

Here's very late in the series, in LIGHT, in the aftermath. A couple of characters in the hospital chatting.

"Edilio is in hiding," Astrid snapped. "Edilio has to be worried about being kicked out of the country. Our Edilio."

"He's got a volunteer lawyer --"

But Astrid wasn't done. "They should be putting up statues to Edilio. They should be naming schools after that boy -- no, no, I'm not going to call him a boy. If he's not a man I'll never meet one."

Does that sound to you as if my purpose was to trash Edilio by calling him a wetback? Or do you think maybe I spent a good part of 3000 pages slowly bringing Edilio along as a character, bringing the readers with me, as I moved him from 'nobody' to 'they should name schools after him?'

You are being unjust to me, Ms. Reese. You were unjust to accuse me of erasure, you were unjust to accuse me of lying, you are being unjust now to act as though 'wetback' is how I think of Hispanics when it is patently obvious that I'm doing just the opposite. You are unjust to toss in the description of a black kid as black with what implication? That's another cheap shot, and if you actually read my books you'd know that. But you don't read the book, you cherry-pick scenes out-of-context and wave them around like a bloody shirt and call that a review. That is unfair and it is unjust.

DR: Grant thinks I and Corinne Duyvis are wrong to point out these problematic representations in his books.

MG: That is flatly false. On the contrary, I wrote:

Criticize? Of course. Comes with the territory. Teach? Of course. Review? Yep. Where I part company is the destruction of books. Mein Kampf is still on the market, and, as a Jew? I would never support banning it. I flatly reject the banning or withdrawing of books.

The issue here is not criticism, I'm a big boy and if criticism scared me, why am I here? The issue to me is book-banning and book-destruction. The issue is freedom of speech and the First Amendment. The issue is the political knock-on effects. The issue is making the perfect the enemy of the good and in the process harming the very cause we both support.

Of course my depictions matter. And had you said to me, "You know dude, maybe this sounds crazy to you, but when a Native American kid sees a Native American character in a book, and then it turns out to be a bunch of nothing, that's disappointing to Native kids," I'd have said, "Huh, I hadn't thought of that. Interesting. I'll keep that in mind and see if I can't look at hiring more Native American characters in bigger roles."

I would like to start having those conversations. I like dialog. But dialog goes both ways. There is no dialog if each time I defend myself the mere fact of defending myself is taken as proof of thought-crime. Let's have a conversation - activists and writers. I'm up for it, I think plenty of writers are.

_____________

Sunday, November 20: Debbie Reese's response to Michael Grant about erasure

Dear Michael,

We have way too many points of disagreement to continue in this same way. How about we focus on single points, working our way through others, later. Let's start with the beginning of our exchange, over at School Library Journal.

I said that you erased Native Americans in one of your books. I asked you to look over your books and see if you could find the one I was referring to. I was pushing you to look critically at your work, but you said there was too much of it for you to do that. You were sure that you hadn't erased Native Americans.

My guess is that you read my remark and thought that I was saying you'd written a story where Native Americans were erased on a large scale and that the erasure was celebrated. Because you haven't written a book like that, you called me a liar. You said I was slandering you and that I owed you an apology.

When I specified the book (Gone), and the character (Grandpa Luke) you dismissed what I'd said because he isn't the only character who disappears. I think it matters, though, because in the larger context of Native and characters of color, these are the ones that are, to use that phrase, 'the first to die.' That's how I read Grandpa Luke's disappearance. He's gone. Erased. Removed from your story. That's similar to what happened to the Native characters in two best selling books: Sign of the Beaver and Little House on the Prairie.

You've been writing books for a long time. I've been studying the ways that writers write Native characters for a long time. I hope this conversation will help you see what I see.

Debbie

_________

Monday, November 21, 2016: Debbie Reese's Response to Michael Grant about Lana's identity

Michael,

I don't know if I'll hear from you anymore, but if you do, I'll insert your replies in the appropriate place. This morning, I'm back with this reply to talk with you or anyone who is interested in understanding the problems with your decisions with respect to Lana's identity.

You introduced her on page 19, partway through chapter two. She's riding in a truck with her grandfather, Grandpa Luke. You tell us he is

Chumash. In my review (up top of this post), I wrote that I thought that was cool because you didn't say he was "part Chumash." When someone is a citizen of a nation, they're a full citizen of that nation. In the U.S., the tribal nations have sovereign nation status because they were nations of people long before Europeans came here. Each one has its own criteria for determining its citizenship. So, it seemed to me you knew about tribal nations and citizenship.

In its interview series with Native leaders, the National Museum of the American Indian has

one with the chairman of the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians. It has lot of good information, including this:

The federal government created Indian reservations even before many western states were established. To remedy the poverty of the Indians in California who were previously part of the Spanish missions, Congress passed the Mission Indian Relief Act of 1891.

I'm sharing that passage in particular because of the reference to the missions (which Raina

Telgemeier misrepresented in Ghosts)

.

But let's get back to Lana. I'm guessing that Grandpa Luke would be a citizen of the Santa Ynez Band. I'm also guessing that Lana would be, too. My expectation--at that early point in the book--was that I'd be pleased as I read on. I thought you'd done some research on Chumash people and would be bringing that into the story. From there, though, what I found was stereotypical.

In your reply on November 18th, you asserted that those items were about something else. They were not, in your mind, related to any effort on your part to signify that Luke and Lana are Chumash. (A note about alcoholism: you said that alcoholism rates are high, but that's not accurate. Research studies show that rates of alcoholism are similar across Native and non-Native populations. See a

Washington Post article, or the

research study the

Post references).

Specific to their identity, you wrote that Luke was a "throw away character." I get it, but am not okay with it. Though this entire conversation has been intense, I think you will make different decisions in creating Native characters, and I think your editors will be more aware of how they're brought into stories, too. That is a plus, for all of us.

Debbie

_____________

Tuesday, November 22, 2016: Debbie Reese to Michael Grant on dialog

Michael?

You still there? Maybe busy with family on this holiday week?

In my head, I'm thinking you're still open to dialog. So... I'll be hearing from you sometime, maybe next week? I hope so!

I hope that your editor didn't tell you to stop. I hear that happens to some writers, so I suppose it is possible in your case, too. Others might have told you to quit, that you're wasting your time with me, but that's a bit of a cop out, I think. You and I aren't the only ones reading this conversation. Your fans are reading, too. And a lot of writers are reading it, too.

So, I hope I'll have another email from you soon.

Debbie