|

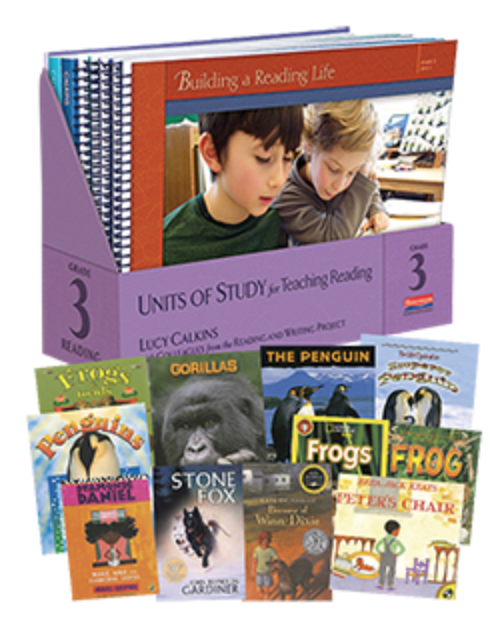

| Stone Fox is shown on bottom row |

Update, September 16, 2018: On the Facebook page for the Units of Study group, Dr. Lucy Calkins announced that they are removing Stone Fox from the Units of Study materials. The new edition (Units of Study is published by Heinemann) will have a different book.

The Facebook group is a closed group but Dr. Calkins said that anybody can request to be added and that "we say yes in seconds." They approved my request a few months ago. I am not a classroom teacher (and not using the materials), but I do study literature and am glad they are open to my participation in conversations.

_________

Stone Fox by John Reynolds Gardiner was published in 1980 by HarperCollins. It is part of a literacy program used in classrooms across the United States: “Units of Study for Teaching Reading”.

Because of its many problems, I do not recommend the book and think that it is vital that Professor Lucy Calkins (she created the Units of Study program) revisit its use in her curriculum.

Leaving it there means she--a trusted educator--is miseducating all the children who are in schools that use her curriculum. That sounds harsh--I know--but a key reason that I'm writing about this book is because Native parents and Native educators have written to me about it.

Here’s the book description, from the HarperCollins website:

Based on a Rocky Mountain legend, Stone Fox tells the story of Little Willy, who lives with his grandfather in Wyoming. When Grandfather falls ill, he is no longer able to work the farm, which is in danger of foreclosure. Little Willy is determined to win the National Dogsled Race—the prize money would save the farm and his grandfather. But he isn't the only one who desperately wants to win. Willy and his brave dog Searchlight must face off against experienced racers, including a Native American man named Stone Fox, who has never lost a race.

The story takes place in the early 1900s, in what is currently known as the state of Wyoming. Prior to European and later, American, invasion, it was Indigenous land. A little over half of what is, today, Wyoming, was part of the Louisiana Purchase. The US bought it from France in 1803--but how and why does that narrative get told that way? Why do history books leave out the fact that it was Indigenous land before it was France or the US claimed it? These are not rhetorical questions! When teachers who teach students in those areas, today, leave out the history of Indigenous peoples, they tell Indigenous students that their history does not matter.

How the people of an Indigenous nation are depicted is also tremendously important. Rather than depicting us as peoples of distinct nations that traded with peoples of other nations, and that had diplomacy with those other nations, we are shown as generic primitive, simple minded children or animal-like savages. None of that is accurate. That is, however, what we see in Gardiner’s Stone Fox.

In that dogsled race, Searchlight (Willy’s dog) will pull a sled that his grandfather had “bought from the Indians” (p. 25). Indians is a generic term. Not naming who he bought the sled from contributes to that generic image that falls into stereotypical thinking. We see that again when Willy learns that the race will be especially exciting this year because “that mountain man, the Indian called Stone Fox” (p. 45) might be in the race, and he has never lost a race he’s entered.

The name that Gardiner created for this Indian man is “Stone Fox.” Chapter six--titled “Stone Fox”--is where readers get details about him. The chapter opens with Willy inside the bank. He’s paid the fees to sign up for the race, gotten a map of the route, and is outside with Searchlight when something catches his eye: Stone Fox’s team of Samoyeds, pulling Stone Fox (p. 50):

The man was an Indian--dressed in furs and leather, with moccasins all the way up to his knees. His skin was dark, his hair was dark, and he wore a dark-colored headband. His eyes sparkled in the sunlight, but the rest of his face was as hard as stone.

Moccasins up to his knees? Furs and leather? While that is plausible, I wonder if it was typical dress at that time. By then, Native peoples wore some of the same clothes that Americans were wearing. A face as hard as stone? Now we see why Gardiner named this character Stone (Fox). That is a common stereotype. Native people are often depicted as stoic--lacking in display of any emotion… rigid, unmoving. Stone Fox brought his sled up to Willy, who tilts his head way back to look up at “a giant” (p. 50):

“Gosh,” little Willy gasped.

The Indian looked at Little Willy. His face was solid granite, but his eyes were alive and cunning.

Cunning! Like…. A fox! Now we know why Gardiner created this name for this Indian. He wants readers to understand that this Indian is hard and cunning. And--he’s a giant! With a face of “solid granite”! All of this is negative stereotyping. Willy greets him, but “the Indian” doesn’t reply. Instead, "the Indian" looks at Searchlight. That makes Searchlight moan. Readers have come to like Searchlight by this point, and its moan tells them that Searchlight is worried or afraid of "the Indian". I'm intentionally using quotation marks for the Indian because Gardiner's repeated use of "the Indian" objectifies and others him. He's a man, for goodness sake. He could say that, instead!

This "Indian" is legendary. There are many stories about him. In Denver, he "snapped a man's back with two fingers." Willy learns a lot about him (p. 53):

Stone Fox refused to speak with the white man because of the treatment his people had received. His tribe, the Shoshone, who were peaceful seed gatherers, had been forced to leave Utah and settle on a reservation in Wyoming with another tribe called the Arapaho.

It is good to finally have some specific tribal nations named in that passage, but “peaceful seed gatherers” plays into the stereotypical idea of primitive Indians. And, there’s more than just one nation with the name Shoshone. In fact, there are several, currently located in California, Oregon, Nevada, Idaho, and Wyoming. Who, specifically is Gardiner talking about? And he tells us they had been forced to leave Utah? By… whom? And… why? And how?! Those are huge gaps in Gardiner’s story.

Biased history and storytelling being what it is, readers fill those gaps with problematic information. Most likely, readers will think about courageous pioneers. But if you think about that history from a Native perspective, the accurate word isn’t pioneer. The right words are squatters and invaders. The next passage is also biased:

Stone Fox’s dream was for his people to return to their homeland. Stone Fox was using the money he won from racing to simply buy the land back. He had already purchased four farms and over two hundred acres.

That Stone Fox was smart, all right.

In that passage, readers learn why Gardiner decided to call this character “Fox” and “cunning” and “smart”? Gardiner doesn’t say so, explicitly, but he’s telling us that Stone Fox has chosen to embrace American capitalism. He’s using money to get that land back. Sounds heroic but what would we find if we looked into the Shoshone peoples and the efforts they made to protect, retain and recover their homelands? What treaties did they make? What parts of those treaties were -- and are -- ignored?

Gardiner tells readers that the Shoshones of his story are in Wyoming, which suggests to us that he’s referring to the Eastern Shoshone, who negotiated the Ft. Bridger treaty in 1863. According to information on the Eastern Shoshone’s website, that treaty established the boundaries for what is currently known as the Wind River Reservation. In size, it was over 44 million acres and it covered parts of Utah, Idaho, Montana, Wyoming, and Colorado. In 1868, a second treaty was negotiated. The outcome of it was that the reservation was reduced to 2,774,400 acres in Wyoming. Today it is approximately 2.2 million acres. With that as context, Stone Fox’s purchase of 200 acres is bit silly to me, but to Gardiner and most readers, it will seem heroic in an American pull yourself-up-with-your-bootstraps kind of way.

A few pages later when Willy reaches out to pet one of Stone Fox’s dogs, he’s surprised by a movement to his right, which turns out to be Stone Fox (p. 59):

A sweeping motion, fast at first; then it appeared to slow and stop. But it didn’t stop. A hand hit little Willy right in the face, sending him over backward.

“I didn’t mean any harm, Mr. Stone Fox,” little Willy said as he picked himself up off the ground, holding a hand over his eye.

Stone Fox stood tall in the darkness and said nothing.

Willy continues talking to Stone Fox, telling him that he (Willie) is going to win the race, and that if he doesn’t, “they” (the government) are going to take their farm away from them. The next day (race day), Willie's eye is swollen shut.

There’s a lot to say about that particular passage in the book. Stone Fox is violent and clearly willing to strike a little boy in the face, knocking him down and hurting that boy’s eye. That plays into the stereotype of the cruel Indian who has no compassion or human-like feelings for others.

It is also interesting to think about why Gardiner has Willie tell Stone Fox about his reason for being in the race. Given what we already know about Stone Fox needing money to buy land for his people, I suspect we’re supposed to make a connection between Stone Fox and Willie. Missing (again) is any reference to the greater injustice that Indigenous peoples experienced at the hands of those who took their lands from them.

Towards the end of this story, Gardiner depicts Stone Fox as a good guy. When Searchlight dies just before crossing the finish line, Stone Fox pulls his sled up beside Willie. He could easily win the race, but instead, he draws a line in the snow and takes out his rifle. When the other racers reach them, he fires his rifle into the air and speaks, for the first time in the story:

“Anyone crosses this line--I shoot.”

That sentence is the way many writers depict Native speech. Where is the word "if" at the start of that sentence, and where is the word "will" in the last part?! After uttering that sentence, Stone Fox nods to Willie, who then carries Searchlight across the finish line, winning the race. He’s gone from Willie’s threat to Willie’s savior, but his “help” is just like he has been throughout: violent. His only words of the entire book are that he will be violent. The stereotypical ways that he is depicted are a problem. They do not interrupt the existing stereotypes that children bring to their reading of Stone Fox. It is a dramatic ending. The story itself is thrilling and teachers report how well it works with reluctant readers. Those who object to the book do so based on the death of Searchlight. That, some feel, is inappropriate content for young readers.

I looked for reviews that are critical of the Native content in Stone Fox and found the following:

The Alaska Native Knowledge Network has some book reviews on its site. Richard Schmitt, a student in ED 693, reviewed it on March 6, 2006. He notes similar problems in stereotyping. In 1991, Christine Jenkins and Sally Freeman raised questions about it in Novel Experiences: Literature Units for Book Discussion Groups in Elementary Grades. So did the teacher, Paul, in McGee and Tompkin’s 1995 article, “Literature-Based Reading Instruction: What’s Guiding the Instruction?” in Language Arts. My point in listing these articles is that the analysis can be done. The problems are there. People have seen then since 1991 (and likely earlier!).

As noted above, Stone Fox ought to be removed from the Units of Study for Teaching Reading program. It will cost the publisher (Heinemann) money to do that, and Calkins will have to spend some time looking for a book to insert in its stead. I don't know that program well enough to suggest an alternative. If you do, let me know in the comments.

****

Some brief notes on the illustrations in Stone Fox

The original illustrations for Stone Fox were done by Marcia Sewell. This is the original cover (1980):

Here’s Sewell’s first illustration of Stone Fox:

More recent publications had a new illustrator, Greg Hargreaves. Here's his depiction of Stone Fox:

Over time, book covers can change quite a lot. These three show the last part of the race, just before Searchlight dies:

Here's an interior page that shows Stone Fox and his team. Do his dogs look mean to you? They do to me! I wondered how dogs look when they're racing. I found lot of photos. Mostly their tongues are hanging out. They don't look mean to me. These ones look kind of... sinister!

Here's the 30th anniversary edition cover.

Stone Fox was also made into a movie, which is evidence of how well this story plays to non-Native readers. And, to Lucy Calkins. And to so many others. But again--the Native content is deeply problematic!

Published in 1980 by HarperCollins, John Reynolds Gardiner's Stone Fox is not recommended.