A reader of AICL wrote to ask me about Gary Paulsen's

Mr. Tucket. I read a copy of the book via the Internet Archive. Here's my notes, summarized by chapter. Sometimes I put my comments in italics beneath each chapter. This time, you'll find my thoughts on the book in the THOUGHTS at the end of the summary of chapters.

First, though, let's look a bit at Gary Paulsen. He's a prolific author and quite well known for

Hatchet and the sequels to it

. The

Hatchet series is also known as Brian's Saga, because the protagonist is a kid named Brian who survives a plane crash, alone, in the Canadian wilderness.

Hatchet was a Newbery Honor Book in 1987.

Published in 1969 by Funk & Wagnalls, I think

Mr. Tucket was Paulsen's first book. It, too, is about survival.

CHAPTER SUMMARIES

Protagonist: Francis Alphonse Tucket, age 14

Date: June 13, 1848

Place: Oregon Trail

CHAPTER ONE

Francis's family is part of a wagon train moving from their farm in Missouri. While in Kansas, they'd been worried about Comanche's but all through Kansas, they hadn't seen "a feather--let alone an Indian" (p. 8).

The wagon train is in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Francis receives a rifle for his 14th birthday. He's out practicing, behind the wagon train and out of sight of everyone. He is captured by "six Pawnee men and one older warrior" (p. 9) who are not wearing paint, which he thinks means it is a hunting party. He struggles, they knock him out. He wakes up at their camp where "the ugliest old person" (p. 10) he's ever seen looks down on him. The person, who has a wrinkled face and toothless mouth, smiles down on him.

CHAPTER TWO

The old woman is wife of the old warrior in the hunting party. When Francis wakes, she puts a rope on him and shows him off at each lodge. Boys kick him. He fights the boys, decides it isn't worth it, and smiles at the old woman. She removes the rope. He is attacked by three boys. The fight is stopped by (p. 14):

"a short, wiry Indian with his hair in one braid. At the bottom of the braid there was one feather, hanging straight down. The man wore plain buckskins, unbeaded moccasins, and carried a rifle in his left hand. It was Francis's rifle."

Francis argues with the man. Aiming the rifle between Francis's eyes, the man warns him not to be stupid or insult elders, and walks off.

CHAPTER THREE

Three weeks after being at the camp, Francis learns that "the brave" with his rifle is named Braid and that he is the leader of their war parties. He is not a chief. There are scalps braided across his doorway to his lodge. One morning he led a party of more than 40 warriors out of camp. When they return, Francis sees a blonde scalp and figures the Pawnees had attacked the wagon train with his family. His suspicion is confirmed when Braid throws a china doll at his feet. It is his sister's doll. The council decides to move the village. They travel for ten days to the southern edge of the Black Hills. There, Francis meets a white man who comes to the village: Mr. Jason Grimes.

CHAPTER FOUR

"Squaws" and children crowd around Grimes, who Francis thinks of as a mountain man. He wears fringed buckskin, plain moccasins, and a derby with a long feather sticking straight up from the band. The people in the village prepare a celebration. At night there is a frenzy of dancing. Francis wakes that night with a hand over his mouth. It is Grimes, with a plan for how Francis can get away.

CHAPTER FIVE

Francis takes off on a mare Grimes swiped for him. He rides the mare, loses it, and keeps walking. At dark, he falls asleep.

CHAPTER SIX

Francis wakes to the smell of coffee. Grimes is there. He tells Francis he followed Braid and five or six others as they tried to find him by following the mare's tracks. Having gone upriver without the mare, Francis--now called Mr. Tucket by Grimes--is safe. He learns that Grimes lost his arm after a fight with Braid.

CHAPTER SEVEN

Grimes teaches Mr. Tucket how to use the rifle and be aware of surroundings.

CHAPTER EIGHT

Francis asks Grimes why he is friendly with Pawnees after having lost his arm due to the fight with Braid. Grimes says Pawnee can't help the way they are, that nobody can. Then he says the Pawnee call themselves "the People" and that they "live with the land" or, (p. 50):

"by nature--the same nature that makes a she-bear gut you if you mess with her cubs. Braid costing me my arm is about the same as a she-bear took it. I couldn't get mat at a bear and I couldn't get mad at Braid, and I couldn't hate the whole Pawnee tribe because of a mistake."

The mistake was that Grimes wasn't successful in preventing Braid from cutting his arm up. Francis asks questions that make Grimes uncomfortable. Why does he trade pelts for gunpowder and lead that the Pawnees then use on white people? Grimes says he is not a war maker. He doesn't want to kill Pawnees or whites. If he does kill Braid it will not be over land. That desire for land is what farmers like Francis's family wants. He asks Grimes to leave him at a settlement. Grimes says the closest one is Standing Bear's Sioux village.

CHAPTER NINE

They ride into the Sioux village where "the children's howling was earshattering" (p. 56). At the center of the village, (p. 56)

"a small channel opened in the crowd to the right and an Indian, who limped, came through. He was short, bowlegged, and stocky, but he moved with a smoothness that make Francis think immediately of a cat. It must be Standing Bear, Francis thought, and he was not smiling."

Grimes speaks in Sioux to Standing Bear, who tells him that Braid asked Standing Bear to keep an eye out for Francis. This strikes Grimes as unusual because the Pawnee and Sioux are enemies, but it turns out the mare Francis escaped on was Braid's personal horse. Because of that, Braid is willing to talk to enemies, with the hope of getting his mare back. Grimes talks with Standing Bear, apparently asking Standing Bear if he can trap beaver on Standing Bear's lands. He gets that permission, and then sets up a wrestling match between Francis and a boy in the village. It starts with Standing Bear "snorting" something in Sioux to both boys. Francis wins the match. His winnings are a horse and outfit.

CHAPTER TEN

Francis tries out the horse. He and Grimes leave the village.

CHAPTER ELEVEN

Francis puts on, and likes, his buckskin outfit. Francis and Grimes set out to hunt antelope using an old Indian trick in which Francis will wave a white rag, which makes the antelope curious. They want to see what it is. When they do, Francis is to shoot a young antelope. They get one and eat twelve pounds by dark.

CHAPTER TWELVE

They visit Spot Johnny. He has an Indian wife named Bird Dance and two boys: Jared, John and Clarence. Bird Dance speaks perfect English. Spot tells Grimes that Braid is thinking of taking over the Pawnee nation, and gathering items like powder for the tribe. Braid has also been raiding wagon trains. Spot says Braid is stupid, wanting to make "a clean sweep" and "driving all whites from Pawnee territory" (p. 91).

Grimes then asks Spot about the Crows, saying (p. 92):

I spent a week coming across their stomping grounds and didn't see a one. Usually I get shot at at least once."

Spot says they're hunting and that he's also heard they've broken into small bands. "Too many war chiefs" (p. 92) and are raiding and taking what they can.

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

Francis and Grimes leave Spot Johnny's place. They see a wagon train, but Francis chooses to stay with Grimes.

CHAPTER FOURTEEN

They enter an area where Grimes is careful to cover their tracks so that "the best Kiowa tracker in the world" won't be able to find them. They're near the edge of the Crow territory. They settle near beaver ponds.

CHAPTER FIFTEEN

Jim Bridger comes for a visit and tells Francis and Grimes about a Crow family nearby.

CHAPTER SIXTEEN

Francis and Grimes trap two hundred beaver, skin and stretch their pelts.

CHAPTER SEVENTEEN

Two miles from camp, five Crows "painted for war" (p. 129) fire arrows at Francis. He races back to camp, with them chasing and firing arrows. Grimes shoots two, and one is thrown from his horse and injured. Grimes and Francis plan to get the others.

CHAPTER EIGHTEEN

Grimes and Francis come upon two of the Indians (p. 136):

"In front of them, not ten feet away, two painted faces and bronze chests rose. Two arrows were pulled back on taut strings. Two Indian throats let out a roaring sound."

Francis wounds one; Grimes kills him. The other "brave" got away. Grimes and Francis start tying beaver pelts to horses, and then leave. Back at their camp, ten Crow "braves." The leader says they will start out to find Grimes and Francis at daybreak, and help Laughing Pony (the one who was thrown from his horse).

CHAPTER NINETEEN

Grimes and Francis run into a heavy snowstorm but keep running the horses until Francis's mare stumbles. They stop for the night.

CHAPTER TWENTY

The next morning they set out again, rest again, and then when they get started they see smoke. Grimes thinks it is from Spot Johnny's camp but that there is too much smoke.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

When they arrive at Spot Johnny's camp, everything is on fire and there are many bodies. Grimes says it was "Braid and his boys" (p. 154). Two miles away, Spot Johnny's trading post and wagons from a wagon train are also on fire. There are twenty-three dead Pawnees, too. Grimes and Francis don't find Spot or his family outside, and Grimes is sure they were in the burned trading post. There are farmers at the wagons. Grimes asks them when they were attacked and says it is time for him to "do something about Braid" (p. 156). He asks the farmers to keep Francis as he rides off and if he doesn't return, that Francis gets his ponies and pelts, and that the farmers should take Francis with them.

CHAPTER TWENTY-TWO

Francis gets away from the farmers. He rides hard to catch up to Grimes. He sees Grimes and Braid in a meadow, on horses, racing towards each other, both "stripped to the waist and carrying rifles" (p. 163). They shoot at each other, and "the one-armed and one-braided men" fall near each other. Braid is dead. Francis is shocked that Grimes goes to scalp Braid. He realizes Grimes is like the Indians, and "in a way, a kind of animal" (p. 165) and that he (Francis) is not. He gets on his horse and sets out for Oregon.

MY THOUGHTS

Though I am glad to see that Paulsen used specific tribes (examples: Pawnee and Kiowa) in

Mr. Tucket, it is disappointing that the Native characters are, nonetheless, portrayed as animal-like rather than as human beings. The Pawnee children howl, for example, in chapter two. In chapter eight, Grimes frames the Pawnees as being like bears. In chapter nine, Standing Bear (a Sioux) moves like a cat. None of this characterization is used for the white characters.

Paulsen's Standing Bear is Sioux. There was a man named Luther Standing Bear/Ota Kte (Ota Kte is his Lakota name), born in the 1860s, who wrote several books, including

My People the Sioux. There was a Ponca leader named Standing Bear. He was born in 1829 and died in 1908. He is known for leaving his reservation, without permission, to take his son's remains to their homelands to bury them there.

Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve's book about him is on my list of children's books to review. I wonder if either of them was the inspiration for Paulsen's use of that name for that character? Both are men of significance, and I was annoyed to see that name for this character.

I'm also curious about the name of the Pawnee man: "Braid." He wears a braid, and my guess is, that braid is why he's called Braid. To me, it sounds silly. I searched for images/photos/illustrations of Pawnee men to see how they wear feathers. Paulsen's Braid wears a feather at the end of his braid, pointing down. That seems silly, too, and I didn't find any examples of a feather being worn that way. I'm not saying it isn't possible--anything IS possible--but when we have an outsider (Paulsen) creating characters from a nation (Pawnee) and a time period over 100 years ago, I think Paulsen is on a slippery slope.

The wrestling. I can't find any support for wrestling, in any tribe, that looks like what Paulsen describes. I do find it, however, in boy scout manuals! There is a lot in those scouting guides that gets labeled "Indian" that isn't part of Native traditions anywhere. I would love to find some kind of evidence of it, though, so if YOU find it, do write and let me know where it is! This wrestling reminds me of the "Indian burn" that is part of kid lore in the U.S.

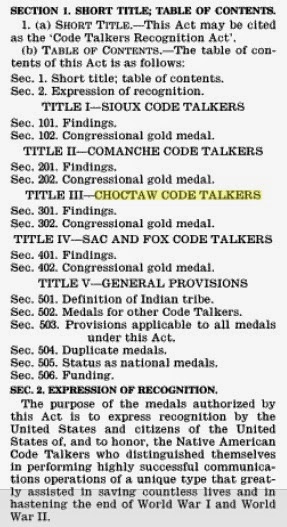

Scalping. Braid does it. A lot. It is a brutal, savage act. Overall, Paulsen characterizes the Native people as more like animals. The scalping that Braid does fits in a savage framework, with Pawnees portrayed as less-than-human. At the end of the story, Francis chooses to abandon his friendship with Grimes when Grimes behaves like a Pawnee and scalps Braid. We are supposed to think that Francis has higher morals, that he's choosing not to be animal-like. BUT. What we--as readers--ought to reject is Paulsen's characterizations of Native people. He gives us is a narrow depiction that serves a narrative that encourages readers to think Native people were less-than White people, and therefore, it was ok to take Native land. And, it obscures a lot of the violence directed at Native people, too. There were bounties on Native men AND Native women and children, too. Bounty hunters would collect their money by showing the scalps of Native men, women, and children. Paulsen gives us one White person who scalps, but in Paulsen's story, he is the exception. He's shown to be outside-the-norm, but the fact is, Whites scalping Native people happened a lot. Here's an excerpt of a

proclamation from 1755 that specifies how much a person would receive when he would "produce the scalp":

For every Male Penobscot Indian above the Age of twelve years that shall be taken within the Time aforesaid and brought to Boston Fifty Pounds.

For every Female Penobscot Indian taken and brought in as aforesaid and for Every Male Indian Prisoner under the age of twelve Years taken and brought in as aforesaid Twenty five Pounds.

For every Scalp of such Female Indian or Male Indian under the Age of twelve years that Shall be killed and brought in as Evidence of their being killed as aforesaid, Twenty pounds.

Paulsen's point of view is Francis's--a 14 year old white boy--but, as the

reviewer of his third book (

Tucket's Ride) said, Paulsen doesn't develop characters. He uses stereotypes. When we, as a society, know so little about Native peoples--past and present--such stereotyping is a serious issue. The reviewer points to that issue, saying:

"Classroom use for social studies, however, would require careful and critical analysis by teachers and students."

I spent an hour or so looking over videos students/teachers have made about

Mr. Tucket.

I see no evidence of careful or critical analysis. Though Paulsen sometimes had his white characters use 'man' or 'men' to refer to the Pawnee men, he mostly used "brave" or "warrior" for men and "squaw" for women. In careful or critical analysis, I'd like to see teachers looking at words like that, because they create a distance, or a barrier, in thinking about Native men and women as people, just like any other people.

Mr. Tucket is definitely a very popular book, as evident in its reprintings. Here's some of the covers I've found. First is one that looks like it could be the original cover, from 1969:

Here's one I found a lot. Looking at a preview online, I saw a copy from 1995, that, with this cover, was in its 25th printing.

And here's what I think is the most recent cover:

In an

interview, Paulsen says he learned a lot from reading a particular series. What are kids who read his

Mr. Tucket series "learning" about Native people? Regular readers of AICL know that I'm critical of authors who use "Indian" rather than a specific tribe, but when an author uses a specific tribe and gives us stereotypes anyway, that is equally problematic. I cannot recommend

Mr. Tucket.