Some people read my reviews and think I'm being too picky because I focus on seemingly little or insignificant aspect of a book. The things I pointed out in March were not noted in the starred reviews by the major review journals, but the things I pointed out have incensed people who, apparently, fear that my review will persuade the Caldecott Award Committee that The Secret Project does not merit its award.

In fact, we'll never know if my review is even discussed by the committee. Their deliberations are confidential. The things I point out matter to me, and they should matter to anyone who is committed to accuracy and inclusivity in any children's books--whether they win awards or not.

****

The Secret Project, by Jonah and Jeanette Winter, was published in February of 2017 by Simon and Schuster. It is a picture book about the making of the atomic bomb.

I'm reading and reviewing the book as a Pueblo Indian woman, mother, scholar, and educator who focuses on the ways that Native peoples are depicted in children's and young adult books.

I spent (and spend) a lot of time in Los Alamos and that area. My tribal nation is Nambé which is located about 30 miles from Los Alamos, which is the setting for The Secret Project. My dad worked in Los Alamos. A sister still does. The first library card I got was from Mesa Public Library.

Near Los Alamos is Bandelier National Park. It, Chaco Canyon, and Mesa Verde are well known places. There are many sites like them that are less well known. They're all through the southwest. Some are marked, others are not. For a long time, people who wrote about those places said that the Anasazi people lived there, and that they had mysteriously disappeared. Today, what Pueblo people have known for centuries is accepted by others: present-day Pueblo people are descendants of those who once lived there. We didn't disappear.

What I shared above is what I bring to my reading and review of The Secret Project. Though I'm going to point to several things I see as errors of fact or bias, my greatest concern is the pages about kachina dolls and the depiction of what is now northern New Mexico as a place where "nobody" lived.

"In the beginning"

Here is the first page in The Secret Project:

In the beginning, there was just a peaceful desert mountain landscape,The illustration shows a vast and empty space and suggests that pretty much nothing was there. When I see that sort of thing in a children's book, I notice it because it plays into the idea that this continent was big and had plenty of land and resources--for the taking. In fact, it belonged (and some of it still belongs) to Indigenous peoples and our respective Native Nations.

"In the beginning" works for some people. It doesn't work for me because a lot of children's books depict an emptyness that suggests land that is there for the taking, land that wasn't being used in the ways Europeans, and later, US citizens, would use it.

I used the word "erase" in my first review. That word makes a lot of people angry. It implies a deliberate decision to remove something that was there before. Later in the book, Jonah Winter's text refers to Hopi people who had been making kachina dolls "for centuries." His use of "for centuries" tells me that the Winter's knew that the Hopi people pre-date the ranch in Los Alamos. I could say that maybe they didn't know that Pueblo people pre-date the ranch--right there in Los Alamos--and that's why their "in the beginning" worked for them, but a later illustration in the book shows local people, some who could be Pueblo, passing through the security gate.

Ultimately, what the Winter's they knew when they made that page doesn't really matter, because intent does not matter. We have a book, in hand. The impact of the book on readers--Native or not--is what matters.

Back in March, I did an update to my review about a Walking Tour of Los Alamos that shows an Ancestral Pueblo very near Fuller Lodge. Here's a map showing that, and a photo of that site

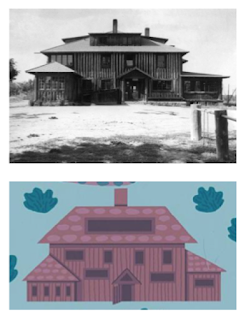

The building in Jeanette Winter's illustration is meant to be the Big House that scientists moved into when they began work at the Los Alamos site of the Manhattan Project. Here's a juxtaposition of an early photograph and her illustration. Clearly, Jeanette Winter did some research.

In her illustration, the Big House is there, all by itself. In reality, the site didn't look like that in 1943. The school itself was started in 1917 (some sources say that boys started arriving in 1918), but by the time the school was taken over by the US government, there were far more buildings than just that one. Here's a list of them, described at The Atomic Heritage Foundation's website:

The Los Alamos Ranch School comprised 54 buildings: 27 houses, dormitories, and living quarters totaling 46,626 sq. ft., and 27 miscellaneous buildings: a public school, an arts & crafts building, a carpentry shop, a small sawmill, barns, garages, sheds, and an ice house totaling 29,560 sq. ft.I don't have a precise date for this photograph (below) from the US Department of Energy's The Manhattan Project website. It was taken after the project began. The scope of the project required additional buildings. You see them in the photo, but the photo also shows two of the buildings that were part of the school: the Big House, and Fuller Lodge (for more photos and information see Fuller Lodge). I did not draw those circles or add that text. That is directly from the site.

Here's the second illustration in the book:

The boys who went to the school in 1945 were not from the people whose families lived in that area. An article in the Santa Fe New Mexican says that:

The students came from well-to-do families across the nation, and many went on to Ivy League colleges and prominent careers. Among them were writer Gore Vidal; former Sears, Roebuck and Co. President Arthur Wood; Hudson Motor Co. founder Roy Chapin; Santa Fe Opera founder John Crosby; and John Shedd Reed, president for nearly two decades of the Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway.

The change from a school to a laboratory

In his review of The Secret Project, Sam Juliano wrote that this take over was "a kind of eminent domain maneuver." It was, and, as Melissa Green said in a comment at Reading While White's discussion of the book,

In her review Debbie Reese observed an elite boy’s school — Los Alamos Ranch School — whose students were “not from the communities of northern New Mexico at that time.” Of course not: local kids wouldn’t have qualified — local kids wouldn’t be “elite”, because they wouldn’t have been white. The very school whose loss is mourned (at least as I can tell from the reviews: I haven’t yet read the book) is a white school built on lands already stolen from the Pueblo people. And the emptiness of the land, otherwise…? It wasn't empty. But even when Natives are there, we white people have a bad habit — often a willful habit — of not seeing them.Green put her finger on something I've been trying to articulate. The loss of the school is mourned. The illustration invites that response, for sure, and I understand that emotion. Green notes that the land belonged to Pueblo people before it became the school and then the lab ("the lab" is shorthand used by people who are from there). There's no mourning for our loss in this book. Honestly: I don't want anyone to mourn. Instead, I want more people to speak about accuracy in the ways that Native people are depicted or left out of children's books.

The Atomic Heritage Organization has a timeline, indicating that people began arriving at Los Alamos in March, 1943. On the next double paged spread of The Secret Project, we see cars of scientists arriving at the site. On the facing page, other workers are brought in, to cook, to clean, and to guard. The workers are definitely from the local population. Some people look at that page and use it to argue that I'm wrong to say that the Winter's erased Pueblo people in those first pages, but the "nobody" framework reappears a few pages later.

By the way, the Manhattan Project Voices site has oral histories you can listen to, like the interview with Lydia Martinez from El Rancho, which is a Spanish community next to San Ildefonso Pueblo.

The next two pages are about the scientists, working, night and day, on the "Gadget." In my review, I am not looking at the science. In his review, Edward Sullivan (I know his name and work from many discussions in children's literature circles) wrote about some problems with the text of The Secret Project. I'm sharing it here, for your convenience:

There was no "real name" for the bomb called the Gadget. "Gadget" was a euphemism for an implosion-type bomb that contained a plutonium core. Like the "Fat Man" bomb dropped on Nagasaki, Gadget was officially a Y-1561 device. The text is inaccurate in suggesting work at Site Y involved experimenting with atoms, uranium, or plutonium. The mission of Site Y was to create a bomb that would deliver either a uranium or plutonium core. The plutonium used in Gadget for the Trinity test was manufactured at a massive secret complex in Hanford, Washington. Uranium, used in the Hiroshima bomb, was manufactured at another massive secret complex in Oak Ridge, Tennessee. There are other factual errors I'm not going to go into here. Winter's audacious ambition to write a picture book story about the first atomic bomb is laudable but there are too many factual errors and omissions here to make this effort anything other than misleading.

The art of that area...

The text on those pages is:

Outside the laboratory, nobody knows they are there. Outside, there are just peaceful desert mountains and mesas, cacti, coyotes, prairie dogs. Outside the laboratory, in the faraway nearby, artists are painting beautiful paintings.In my initial review, I noted the use of "nobody" on that page. Who does "nobody" refer to? I said then, and now, that a lot of people who lived in that area knew the scientists were there. They may not have been able to speak about what the scientists were doing, but they knew they were there. The Winter's use of the word "nobody" fits with a romantic way of thinking about the southwest. Coyotes howling, cactus, prairie dogs, gorgeous scenery--but people were there, too.

I think the text and illustration on the right are a tribute to Georgia O'Keeffe who lived in Abiquiu. I think Jeanette Winter's illustration is meant to be O'Keeffe, painting Pedernal. That illustration is out of sync, timewise. O'Keeffe painted it in 1941, which is two years prior to when the scientists got started at Los Alamos.

The next double-paged spread is one that prompted a great deal of discussion at the Reading While White review:

The text reads:

Outside the laboratory, in the faraway nearby, Hopi Indians are carving beautiful dolls out of wood as they have done for centuries. Meanwhile, inside the laboratory, the shadowy figures are getting closer to completing their secret invention.In my initial review, I said this:

Hopi? That's over 300 miles away in Arizona. Technically, it could be the "faraway" place the Winter's are talking about, but why go all the way there? San Ildefonso Pueblo is 17 miles away from Los Alamos. Why, I wonder, did the Winter's choose Hopi? I wonder, too, what the take-away is for people who read the word "dolls" on that page? On the next page, one of those dolls is shown hovering over the lodge where scientists are working all night. What will readers make of that?Reaction to that paragraph is a primary reason I've done this second review. I said very little, which left people to fill in gaps.

Some people read my "why did the Winter's choose Hopi" as a suggestion that the Winter's were dissing Pueblo people by using a Hopi man instead of a Pueblo one. That struck me as an odd thing for that person to say, but I realized that I know something that person doesn't know: The Hopi are Pueblo people, too. They happen to be in the state now called Arizona, but they, and we--in the state now called New Mexico, are similar. In fact, one of the languages spoken at Hopi is the same one spoken at Nambé.

Some people thought I was objecting to the use of the word "dolls" because that's not the right word for them. They pointed to various websites that use that word. That struck me as odd, too, but I see that what I said left a gap that they filled in.

When I looked at that page, I wondered if maybe the Winter's had made a trip to Los Alamos and maybe to Bandelier, and had possibly seen an Artist in Residence who happened to be a Hopi man working on kachina dolls. I was--and am--worried that readers would think kachina dolls are toys. And, I wondered what readers would make of that one on the second page, hovering over the lodge.

What I was asking is: do children and adults who read this book have the knowledge they need to know that kachina dolls are not toys? They have spiritual significance. They're used for teaching purposes. And they're given to children in specific ways. We have some in my family--given to us in ways that I will not disclose. As children, we're taught to protect our ways. The voice of elders saying "don't go tell your teachers what we do" is ever-present in my life. This protection is there because Native peoples have endured outsiders--for centuries--entering our spaces and writing about things they see. Without an understanding of what they see, they misinterpret things.

The facing page, the one that shows a kachina hovering over the lodge, is not in full color. It is a ghost-like rendering of the one on the left:

We might say that the Winter's know that there is a spiritual significance to them, but the Winter's use of them is their use. Here's a series of questions. Some could be answered. My asking of them isn't a quest for answers. The questions are meant to ask people to reflect on them.

- Would a Hopi person use a kachina that way?

- Which kachina is that? On that first page, Jeanette Winter shows several different ones, but what does she know about each one?

- What is Jeanette Winter's source? Are those accurate renderings? Or are they her imaginings?

- Why did Jeanette Winter use that one, in that ghost-like form, on that second page? Is it trying to tell them to stop? Is it telling them (or us) that it is watching the men because they're doing a bad thing?

In the long exchange at Reading While White, Sam Juliano said that information about kachina dolls is on Wikipedia and all over the Internet. He obviously thinks information he finds is sufficient, but I disagree. Most of what is on the Internet is by people who are not themselves, Native. We've endured centuries of researchers studying this or that aspect of our lives. They did not know what they were looking at, but wrote about it anyway, from a White perspective. Some of that research led to policies that hurt us. Some of it led to thefts of religious items. Finally, laws were passed to protect us. One is the Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978 (some good info here), and another is the Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act, passed in 1990. With that as context, I look at that double-paged spread and wonder: how it is going to impact readers?

The two page spread with kachinas looks -- to some people -- like a good couple of pages because they suggest an honoring of Hopi people. However, any "honoring" that lacks substance is just as destructive as derogatory imagery. In fact, that "honoring" sentiment is why this country cannot seem to let go of mascots. People generally understand that derogatory imagery is inappropriate, but cannot seem to understand that romantic imagery is also a problem for the people being depicted, and for the people whose pre-existing views are being affirmed by that romantic image.

Update, Monday Oct 23, 8:00 AM

Conversations going on elsewhere about the kachina dolls insist that Jeanette Winter knows what she is doing, because she has a library of books about kachina dolls, because she's got a collection of them, and because she's had conversations with the people who made them. Unless she says something, we don't know, and in the end, what she knows does not matter. What we have is in the book she produced. In a case like this, it would have been ideal to have some information in the back matter and for some of her sources to have been included in the bibliography. If she talked with someone at the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office, it would have been terrific to have a note about that in the back matter, too.

Other conversations suggest that readers would know that kachinas have a religious meaning. Some would, but others do not. Some see them as a craft item that kids can do. There are many how-to pages about making them using items like toilet paper rolls. And, there are pages about what to name the kachina dolls being made. Those pages point to a tremendous lack of understanding and a subsequent trivialization of Native cultures.

Curtains

Tribal nations have protocols for researchers who want to do research. Of relevance here is the information at the website for the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office. There are books about researchers, like Linda Tuhiwai Smith's Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples, now in its 2nd edition.

My point: there are resources out there that can help writers, editors, reviewers, teachers, parents and librarians grow in their understandings of all of this.

The Land of Enchantment

The text is:

Sometimes the shadowy figures emerge from the shadows, pale and tired and hallow-eyed, and go to the nearby town.That nearby town is meant to be Santa Fe. See the woman seated on the right, holding a piece of pottery? The style of those two buildings and her presence suggests that they're driving into the plaza. It looks to me like they're on a dirt road. I think the roads into Santa Fe were already paved by then. See the man with the burro? I think that's out of time, too. The Manhattan Project Voices page has a photograph of the 109 E. Palace Avenue from that time period. It was the administrative office where people who were part of the Manhattan Project reported when they arrived in Santa Fe:

You can find other photos like that, too. Having grown up at Nambé, I have an attachment to our homelands. Visitors, past-and-present, have felt its special qualities, too. That’s why so many artists moved there and it is why so many people move there now. I don’t know who first called it “the land of enchantment” but that’s its moniker. Too often, outsiders lose perspective that it is a land where brutal violence took place. What we saw with the development of the bomb is one recent violent moment, but it is preceded by many others. Romanticizing my homeland tends to erase its violent past. The art in The Secret Project gets at the horror of the bomb, but it is marred by the romantic ways that the Winter's depicted Native peoples.

Update, Oct 19, 9:15 AM

Below, in a comment from Sam Juliano, he says that the text of the book does not say that the scientists were going to the plaza in Santa Fe. He is correct. The text does not say that on that page. Here's the next illustration in the book:

That is the plaza. Other than the donkeys, the illustration is accurate. Of course, a donkey could have been there, but it is not likely at that time. If you were on the sidewalk, one of those buildings shown would be the Palace of the Governors. Its "porch" is famous as a place where Native artists sell their work. In the previous illustration, I think Jeanette Winter was depicting one of the artists who sells their work there, at the porch. Here's a present-day photo of Native artists there. (It is, by the way, where I recommend you buy art. Money spent there goes directly to the artist.)

Some concluding thoughts

The Secret Project got starred reviews from Publisher's Weekly, the Bulletin of the Center for Children's Books, The Horn Book, Booklist, and Kirkus. None of the reviews questioned the Native content or omissions. The latter are harder for most people to see, but I am disappointed that they did not spend time (or write about, if they did) on the pages with the kachina dolls.

I fully understand why people like this book. I especially understand that, under the current president, many of us fear a nuclear war. This book touches us in an immediate way, because of that sense of doom. But--we cannot let fear boost this book into winning an award that has problems of accuracy, especially when it is a work of nonfiction.

There are people who think I'm trying to destroy this book. As has been pointed out here and elsewhere, it got starred reviews. My review and my "not recommended" tag is not going to destroy this book.

What I've offered here, back in March, and on the Reading While White page is not going to destroy this book. It has likely made the Winter's uncomfortable or angry. It has certainly made others feel angry.

I do not think the Winter's are racist. I do think, however, that there's things they did not know that they do know now. I know for a fact that they have read what I've written. I know it was upsetting to them. That's ok, though. Learning about our own ignorance is unsettling. I have felt discomfort over my own ignorance, many times. In the end, what I do is try to help people see depictions of Native peoples from what is likely to be their non-Native perspective. I want books to be better than they are, now. And I also know that many writers value what I do.

Now, I'm hitting the upload button (at 8:30 AM on Tuesday, October 17th). I hope it is helpful to anyone who is reading the book or considering buying it. I may have typos in what I've written, or passages that don't make sense. Let me know! And of course, if you've got questions or comments, please let me know.

___________

If you've submitted a comment that includes a link to another site and it didn't work after you submitted the comment, I'll insert them here, alphabetically.

Caldecott Medal Contender: The Secret Project

submitted by Sam Juliano, who asked people to see comments, there, about me (note: tks to Ricky for letting me know I had the incorrect link for Sam Juliano's page. It is correct now.)

Guidelines for Respecting Cultural Knowledge (Assembly of Alaska Native Educators, 2000)

submitted by Melissa Green

Indigenous Intellectual Property (Wikipedia)

submitted by Melissa Green

Intellectual Property Rights (Hopi Cultural Preservation Office)

submitted by Melissa Green

Reviewing While White: The Secret Project

submitted by Melissa Green

30 comments:

Much of what you cover here was already covered in the first review. I think what rankles is not your laser-like focus on a few small things in the book, but that it would in your eyes take the book from outstanding to execrable. You gave this book a one-star review at Amazon. If five stars is outstanding, then one star must be dreadful. It's not dreadful. It's at the very least, as a whole, quite good. It has some elements that you don't like and wish the authors had done differently. I can say the same about just about everything I've ever read. The one star felt destructive, not constructive. It still does.

Debbie, thank you for full disclosure with the reference to my review and for some attempts to at least acknowledge some of the complainst again the substance of your original essay.

I must lodge here a protest in the strongest possible terms to this paragraph:

I do not think the Winter's are racist. I do think, however, that there's things they did not know that they do know now. I know for a fact that they have read what I've written. I know it was upsetting to them. That's ok, though. Learning about our own ignorance is unsettling. I have felt discomfort over my own ignorance, many times.

You "do not think" the Winters are racist. You "do not think" that they are. Why would you have a need to even make reference to that since that was never part of your original opposition to the book? By your wording you purposely leave your readers to ponder the possiblity. The Winters has written books on Frieda Kahlo, the Negro Leagues, Sonya Sotomayor, Roberto Clemente, James Madison Hemings, Jelly Roll Morton, the Voting Rights Act, girls from Kenya and Afghanistan, Malala Yousafzai, and just this year on Iranian Architect Zaha Hadid. Would such writers even remotely work from a racist mindset? You should have stated that their work conclusively affirms they are not anything of the sort, or you should not even broached the subject.

I call on you to remove the paragraph. As to the subsequent paragraph claiming ignorance on the part of the Winters and yourself, I don't even want to go there.

No, Sam, I will not remove that paragraph. Interpret it as you will.

That seems like a major stretch to me, Sam. And funny that you ask Debbie to remove that paragraph, when you submitted how many comments at RWW, PLUS your own review. I think you've said plenty at this point!

Lucille/Sam -

People can work actively to promote social justice or do "ally work" and still say racist things, still create racist books. This past weekend and the #Indivisible10 conference, multiple speakers pointed out the difference between identifying people as racist and identifying acts or representations, etc. as racist. I believe (and please correct me if I'm wrong) that Debbie is clarifying that in pointing out the numerous problematic aspects of this book do not equate to the Winter's being racist. She is trying to help readers avoid making a false equivalency. The Winter's may be lovely people (I don't know them) that does not erase problems in the book.

This gets at the issue of intention versus impact. The books that the Winters have previously published don't actually say anything about if they are, or are not, racist. The tell us what they found to be interesting subjects and what publishers thought was worth putting in the world.

By critiquing Debbie, you are ignoring HER experiences and problematic representations in this book. You are perpetuating privilege colonized views of the world as the "right" way. By asking Debbie to delete a paragraph you are both silencing and censoring her. I call on you to actually engage with and acknowledge the substantive critiques she has shared here and to apologize to her for such a demeaning post.

Of course it would seem to be a "major stretch" to you Sam. You are a site moderator at RWW and are ever vigilant to racial slights or slurs. I remain appalled that it needed even to be said, and many others in the book community are seething as well. If I had written such a statement and someone called me out on it and asked it to be removed I'll immediately oblige. I find it so ironic for you to question my interpretation of a very sensitive subject, yet are are fully abreast of every inference that runs counter as you closely monitor new releases.. When someone will tell you certain scene specific observations are a stretch you rail on with protective agenda. But I am not allowed to stand vigilant to the Winters' artistic integrity? Right.

Where in the many comments at the now disabled RWW thread or in my own review did I even as much as suggest that racism was afoot from either side of the fence? Are you kidding me? I'll let the Winters' past body of work speak for itself.

Kristin: I am not ignoring her experiences or problematic respresentations, I am challenging her conclusions, and her grossly unfair one-star rating, and online (Amazon included) mauling of the book. Please spare me the lectures on colnialism, that was never even an issue in this book. And stop trying to deny me my opinion with the incessant group think and self-righteousness. Multiple times in thsi review Debbie reminded her readership she is a "children's book scholar" in her typical infallibility mode.

I call on you to retract your insulting words to me ASAP! Nice try to turn the tables.

"This gets at the issue of intention versus impact. The books that the Winters have previously published don't actually say anything about if they are, or are not, racist. The tell us what they found to be interesting subjects and what publishers thought was worth putting in the world."

This is PRECISELY why I thought the paragraph should be stricken. The very fact that you Kristen are by your very words leaving the door open by veering off into "appealing subject" territory shows that you too are of this same appalling mindset. As the Winters continue to hold the torch for ethnic diversity, there are still people like you out with medieval mindsets.

Debbie, can I ask you a direct question here?

I wasn't expecting to see the exerpt from Ed Sullivan's review as his issues (again matters that were in a severe minority in the critical ranks) are not by your previous admission under your critical radar so to speak. Your issues with the book were not connected to technical concerns not related to the Native American objections. Can you or will you briefly explain why you felt you needed to include it here?

Thank you.

I am continuing to read and absorb the full review.

I reserve the right to address or include whatever I want to, Sam, in any review I write.

Sullivan addressed accuracy. I'm addressing accuracy.

Under the definition of a picture book, the ALA's page on Terms and Criteria says that a picture book being considered for the award:

"... displays respect for children’s understandings, abilities, and appreciations."

I think accuracy of illustrations falls under consideration of respect for children's understandings, abilities, and appreciations. Accuracy is not included in the Criteria section, but I think it is something people on the committee might be interested in.

That said, my review says "Not Recommended." My review has a broader audience than only Caldecott committee members.

"I reserve the right to address or include whatever I want to, Sam, in any review I write.

Sullivan addressed accuracy. I'm addressing accuracy."

Fair enough then Debbie. I was under the mistaken impression based on some of your prior statements that the issues were exclusively from a Native American point of view and how the book might impact Nation American readers and their position in the children's book community. Now those concerns have expanded. I see.

As to accuracy, I'm afraid that the Caldecott committee's rules need to be adhered to without undue influence. I have been rightfully reminded of that a few times over teh years.

Thank you for responding to me.

{PART 1 OF 3}

(Sorry, this is a long one again, so I’ve broken it into three parts.)

I had intended this as a reply to Sam Juliano's last comment at the RWW discussion of this book <"Reviewing While White: The Secret Project," http://readingwhilewhite.blogspot.com/2017/04/reviewing-while-white-secret-project.html>, but as comments have been shut down over there & the conversation has moved to here, this seems the best place to put it.

Sam J.: in your last comment at RWW, you wrote: "....the internet was LOADED, LOADED, LOADED with references to Kachina dolls. Only when pressed to explain why she had an issue with something even noted Native Americans have confirmed she then tried to claim there was some hidden inflamatory connotation to their use in that extraordinarily soulful and celebratory illustration."...

(The sentence I excerpted mentions Beverly, but most of your post was about Debbie, so I'm guessing she's the "she" you're referring to here....)

What I've observed throughout the conversation at RWW is that you haven't been able to "get" (so far) what Debbie's been trying to say, & she's been unsuccessful (& so has everybody else) in helping you to "get" it. I'd like to give it a try. If you do "get" it, you still may disagree, but at least we'll have a common understanding of at least one element here.

With reference to kachina dolls, in the original conversation at RWW, Debbie asked (on Oct. 13), "Do you know what they are, Sam? To the people who make them?"

Your answer on Oct. 13 was basically the same as you still have today: "Debbie, I do not know what they are to the people who made them as far as your scene-specific question goes.... I mean we all can see what we choose to see. I also see this as Native Americans showing respect for the environment while the white government emissaries are engaged in the worst violation of our resources. A passionate and responsible classroom teacher or librarian would surely point this out."

Debbie had her answer: You don't know what kachina dolls mean to the people who make them. You do know certain things about them that you've read at various websites, and you also do know what you've interpreted them to mean, at least in the context of The Secret Project. And in light of your knowledge, you consider their use in The Secret Project to be a beautiful honoring of Native people.

But that is your understanding of them (possibly also the Winters') — entirely divorced from what they mean to the makers of kachina dolls and their intended recipients. Even if the meaning that you've applied to them (& presumably the Winters) seems beautiful & good, that's taking someone else's intellectual & spiritual property, without permission, for a completely different use. It's removing the meaning the makers of kachina dolls have invested in them, & replacing it with your own.

Debbie: You’ve created yet another amazing, detailed review; a keeper for sure.

Sam Juliano: That Debbie has to remind you (constantly) of her credentials—as a citizen of Nambé, as an Indian parent, as an educator, and as a long-time scholar in the field of children’s literature—attests to her experience, dedication, and incredible patience with white people who engage in what Dr. Joyce King has posited as “dysconscious racism.”

The Winters have created a problematic book, and Debbie has called them out on it and used it as a tool to educate. That’s her job, as well as the job of those others of us who work in this field. She has not called the Winters “racist” and I don’t remember her ever using that term publicly about any author or illustrator. But “artistic integrity” is not a thing when you hold it up to the damage it can cause to children. You need to pay attention, rather than constantly engaging in defensive, self-aggrandizing, contemptuous, hyperbolic nonsense. Please sit down and pay attention. Thank you.

{PART 2 OF 3}

In the mid-'90s when I was going through the MFA program at University of Alaska Anchorage, a Tlingit classmate of mine taught me a term I hadn't known before: indigenous intellectual property. But it's not a new issue. It's been around for a long time.

I'm okay using Wikipedia as a starting point (I've done some Wikipedia editing myself here & there): here's the first paragraph of their article

"Indigenous intellectual property is an umbrella legal term used in national and international forums to identify indigenous peoples' rights to protect their specific cultural knowledge and intellectual property."

In my home turf, Alaska, the Assembly of Alaska Native Educators in 2000 adopted "Guidelines for Respecting Cultural Knowledge" that has also been endorsed by the Alaska Federation of Natives, the Alaska Department of Education, the University of Alaska statewide system, and other important Alaska organizations & institutions, both Native & non-Native.

Alaska Natives are not alone in seeking to preserve their intellectual property. To the point: in its present state, the Wikipedia article I cited above even has a subsection titled Hopi & Apache Opt Out From American Museums. Unfortunately the facts presented there date back only as far as 1998 (per its reference). But in this review, Debbie provided a more direct resource about Hopi efforts to protect their cultural knowledge, the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office. On its page on Intellectual Property Rights, HCPO writes [emphases added]:

Through the decades the intellectual property rights of Hopi have been violated for the benefit of many other, non-Hopi people that has proven to be detrimental. Expropriation comes in many forms. For example, numerous stories told to strangers have been published in books without the storytellers' permission. After non-Hopis saw ceremonial dances, tape recorded copies of music were sold to outside sources. Clothing items of ceremonial dancers have been photographed without the dancers’ permission and sold. Choreography from ceremonial dances has been copied and performed in non-sacred settings. Even the pictures of the ceremonies have been included in books without written permission. Designs from skilled Hopi potters have been duplicated by non-Hopis. Katsinas dolls have also been duplicated from Hopi dancers seen at Hopi. Although the Hopi believe the ceremonies are intended for the benefit of all people, they also believe benefits only result when ceremonies are properly performed and protected.

All of these actions are breaches of Hopi intellectual property rights, used by non-Hopi for personal and commercial benefit without Hopi permission.

Through these thefts, sacred rituals have been exposed to others out of context and without Hopi permission. Some of this information has reached individuals for whom it was not intended (e.g., Hopi youth, members of other clans, or non-Hopi).

Please be mindful of the personal ethics involved in and laws surrounding this issue.

{PART 3 OF 3}

This is what's at the heart of Debbie's issue with the use of kachina dolls in The Secret Project. Throughout the conversation at RWW, and again in this review, she's several times stated that her own silence about the meaning of kachina dolls is in order to protect her people's ways from appropriation. She also said this (on Oct. 13):

"I am not saying the Winter's appropriated anything in their book. I don't think they understood what they were doing. If they did, would they make that choice again?" (As I wrote yesterday at RWW, the unspoken thought here was "hopefully not.")

In today's review, she wrote: I do not think the Winter's are racist. I do think, however, that there's things they did not know that they do know now. Perhaps one thing that the know now, that they didn't know before, is that there are resources like the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office which, like the "Guidelines for Respecting Cultural Knowledge" of the Assembly of Alaska Native Educators, can help guide non-Natives — specifically non-Hopi, actually (since Natives of other peoples might aren't necessarily entitled to Hopi sacred knowlege either) — in how to write about or illustrate Hopi culture & people in ways that truly honor them. In ways that don't misrepresent or appropriate their intellectual & spiritual property.

To answer a charge you made throughout the conversation at RWW (not necessarily at me, but other people anyway), this is not me "piling on." This is me having learned about indigenous intellectual property, starting with what my Tlingit classmate taught me in 1996, and applying it to the present situation. I am sorry for the Winters that they apparently didn't learn about this early enough to evade this error in their book. I hope that after the hurt and discomfort they are no doubt experiencing right now, they can take this new knowledge on-board into new projects.

Personally, I would find it very reassuring to have someone say of me, "I don't think Mel's racist." Because I know I've made plenty of racially or culturally insensitive or ignorant mistakes in my life. It doesn’t feel good at all when they’re discovered, whether someone else points them out to me or I’ve figured them out for myself. It feels wretched. But it’d be even more wretched if I ignored what I had done & did nothing to change. Those words, to me, acknowledge the mistakes I've made, but give me a chance to learn from them & do better going forward. I hope I'm doing so.

If I have misinterpreted statements that either of you have made, I offer my apologies, & ask for correction.

Thank you, Melissa, for your comments here.

In a review, I wrestle with how much to say versus providing a link that people can use to read further.

I'm glad that your comment has that "read further" information, and I appreciate your sharing, too, about your experiences. I don't see anything that is misinterpretation of what I've said here or at Reading While White.

*****

Thank you, Kristin, for calling attention to the #Indivisible10 conference held this past weekend at the Center for Teaching Through Children's Books in Chicago. I followed the hashtag, all the while I had been able to be there with colleagues who were presenting! If readers of this comment are on twitter, check out the hashtag!

*****

And thanks, Sam Bloom and Beverly Slapin, for stopping by and sharing thoughts and comments on the review and discussion. I hope things here don't spin out the way the conversations at RWW did!

"The Winters have created a problematic book, and Debbie has called them out on it and used it as a tool to educate. That’s her job, as well as the job of those others of us who work in this field. She has not called the Winters “racist” and I don’t remember her ever using that term publicly about any author or illustrator. But “artistic integrity” is not a thing when you hold it up to the damage it can cause to children. You need to pay attention, rather than constantly engaging in defensive, self-aggrandizing, contemptuous, hyperbolic nonsense. Please sit down and pay attention. Thank you." -Beverly Slapin

Funny Beverly but "defensive, self grandizing, contemptupous, hyperbolic nonsense" is precisely what I preparing to post about your commentary. In your case though you need to add excessive "sycophancy" to the mix.

What damage has the book caused to children? Are you kidding me. Stop with the dictatorial group think and look around you. The book community has roundly repudiated the conclusion your personal idol has reached. You are not an academic but a cultist.

Oh by the way, I am well aware that the comments here will be nearly 100% pro Debbie. The book itself is secondary to back slapping. Ah group think, group think. Never be specfic, never deal with facts or issues just award carte blanche. Ignore the 95% of teh critical concensus who have practically called the book an American masterpiece. Just defer to Debbie. Her opinion (tainted by a personal agenda on Pueblo representataion) mitigates the entire book community. No one is allowed an opinion. Beverly says to listen and repent. Fascism reigns supreme here. You want the other side to see what others are saying look in the comments here:

https://wondersinthedark.wordpress.com/2017/10/13/caldecott-medal-contender-the-secret-project/

Thank You.

___________

"The best lack all conviction....or just stay out of conversations where those with whom one is talking are not willing to budge a micromilimeter."

Melissa, I stand as firm and as undaunted on this book as the forever intractible Debbie who concedes not an inch as a self-proclaimed and mighty authority on virtually anything academic, but I thought your attempt to unravel this impasse was noble, studied, ever-observant, well-intended and above all passionate. I was riveted all the way through your multi-part presentation.

Not trying to make an ally as you made your position clear at the other site just issuing the kudos you deserve for this.

Thank you!

I'm going to hit the "publish" button on two comments that Sam Juliano has submitted.

After that, I will not publish comments that either praise or denigrate me or anyone else, even if the rest of the comment adds to the conversation.

I'm making that decision in an effort to keep the focus on the book and its impact on readers. Passionate comments about the content are fine.

Before submitting a comment, please look at it to make sure it doesn't praise or denigrate someone, and make sure it isn't an echo of what you have already said.

Thanks!

I am going to try to approach my position a bit differently here. If most or even all of your points in your admittedly exhaustive examination of the book and your issues with it are correct or have serious validity, how do you feel this could possibly impact your readers who you surely understand will be mesmerized by the book's purpose, which is to educate them on the bomb. In view of your last statement about wanting to appraise the entire book community at large and not just a Native American focus I would like to beg your indulgence to render a position on the book's value to first and second grade students who are seeing the book for the first time. These students are predominantly Hispanic and African American. They are unaware of Native American customs and would not be seeing what you are seeing as one privy to past traditions and historical context. What they will see is the book's BIG theme and how it plays out in the desert. I am assuming you may possibly agree with me that their images of the Native Americans would at least be sympathetic and positive, even in the event of some innacuracies?

Debbie, thanks so much for the informative and thoughtful review. I really appreciate all the historical and personal knowledge you brought to it, including the archival photos. Clearly the Winters team didn't do thorough research for this book. The anachronisms alone are enough to cause concern in an informational picture book.

There have been references to this book as a "Caldecott contender." That may or may not be, but why is the Caldecott Medal always held up as a standard by which picture books are measured? There are many great books without medals and many dreadful books with medals. We've made a national sport out of predicting what will win, and I'm not sure that's healthy for books, authors, illustrators, or readers. I, too, used to care deeply about award predictions but after 35 years as a librarian, I find I just can't get all worked up about it. You can never predict the winner, so why not just take each book for what it is -- a book.

"That may or may not be, but why is the Caldecott Medal always held up as a standard by which picture books are measured? There are many great books without medals and many dreadful books with medals. We've made a national sport out of predicting what will win, and I'm not sure that's healthy for books, authors, illustrators, or readers. I, too, used to care deeply about award predictions but after 35 years as a librarian, I find I just can't get all worked up about it. You can never predict the winner, so why not just take each book for what it is -- a book."

I love following and writing about the Caldecotts every year, but would like to express uniform agreement with all K.T. Horning says in this passage. Though I have myself deemed to put the term "Caldecott Contender" before my own review of the book in my annual series and always get worked up with the fun I derive from it. I also of course have been aware that it will be considered in that vein for the Calling Caldecott series.

At 4:43, Sam Juliano asked about the book's impact on first and second grade children.

I believe that teachers have a responsibility to educate children. There is no reason to use a book that misrepresents anyone or any element of history. Using flawed materials is irresponsible.

A teacher who wants to teach students about the development of the atomic bomb can find other ways to do it.

I know Sam wants someone to say that the Hispanic and African American students in his class are gaining something from using this book, but they're also being miseducated.

You see the Native content as a good thing because from your point of view, those images are "positive." I don't think inaccurate or ill-chosen content can be characterized as positive.

A few years ago, a teacher in Ohio wrote to me about the fifth graders she was working with. They were studying Thanksgiving. For the first time, they were learning that the "smiling Indians" they had learned about in her earlier school years were what you might call a "positive" thing. They weren't, and she felt betrayed by the teachers who had given her that sort of information. You can read that student's essay, here:

Do you mean all those worksheets we had to color every year with smiling Indians were wrong?

https://americanindiansinchildrensliterature.blogspot.com/2013/11/taylor-5th-grader-do-you-mean-all-those.html

In short, I think that someday, some children will revisit THE SECRET PROJECT and feel that the teacher who used it betrayed them.

Hi Debbie,

You say you know for a fact that the Winters are aware of your take on their book. Does this mean they have commented publicly or is this insider info? Also, are you suggesting that they are realizing they are wrong?

The reason I ask is that his could be an interesting "teachable" moment if they have in fact changed their minds! Thanks for this thorough review.

M

Debbie, I would like to direct this comment to K.T. Horning, a children's book luminary I greatly respect, but one who in this instance I do not agree with. Horning feels it is clear that "research for the book wasn't thorough" in corroboration with what you asserted about some anachronisms. I am painstakingly gone through the book with Debbie's review at hand:

1. "In the beginning...." at the start of the book. It is an obvious callback to the most famous "in the beginning" of all time, at the start of the biblical Book of Genesis. The Winters are telling an origin story, just like Genesis. Theirs ends in 'let there be light', but in a different way from the biblical narrative, as light of destruction. To see it other way needs funhouse mirrors.

2. The painting woman as Georgia O'Keefe. The text says artists. It doesn't indicate O'Keefe. To say it is definitely O'Keefe and to call it an anachronism again takes funhouse mirrors.

3. The "dirt" road into Santa Fe. The text doesn't say the Plaza. A little research in the local New Mexican newspaper from 1943 (just completed) makes it clear that some Santa Fe roads were unpaved in that era. To say it's the Plaza and that the road should be paved, and this an anachronism, yet again takes funhouse mirrors.

4. The "nobody" knew it was it there. To read this literally, in light of the fact of all the people working there, is inexplical. Los Alamos mail had a post office box in Santa Fe at the time, Box 1663. Obviously, the postal service people knew something was going on up there. As did the food suppliers, etc. "What" was going on, though, was magnificently hidden.

5. To say there was was no "experimentation" with fissionable material on the hill is to funhouse mirror reality. If there was no experimentation, then there wouldn't have been the need for the Alamogordo test..

6. As for the Kachinas, I'm not really sure what the review's point is. Tf it is that no one outside a culture should reuse or reinterpret the sacred objects or stories of from different cultures in their literature, then much of world religion would have to throw out its core texts and self-destruct, especially Islam and Christianity. Count me out. The use of the kachina dolls as I have contended repeatedly was to denote Native American creativity during one of the white man's darkest periods. A negative interpretation here takes tortured logic and goes against the grain of what this book is really about.

To your point 6, Sam J —

A partial requote from the Hopi Cultural Preservation Office's page on "intellectual property) (Debbie has kindly added the link at the end of her post) [emphases added]:

Katsinas dolls have also been duplicated from Hopi dancers seen at Hopi. Although the Hopi believe the ceremonies are intended for the benefit of all people, they also believe benefits only result when ceremonies are properly performed and protected.

All of these actions are breaches of Hopi intellectual property rights, used by non-Hopi for personal and commercial benefit without Hopi permission.

Through these thefts, sacred rituals have been exposed to others out of context and without Hopi permission. Some of this information has reached individuals for whom it was not intended (e.g., Hopi youth, members of other clans, or non-Hopi).

Please be mindful of the personal ethics involved in and laws surrounding this issue.

Of course there's been all kinds of reinterpretation of "sacred objects or stories of from different cultures" by people foreign to those cultures. That doesn't make it right. It's intellectual property. To me, it's tantamount to copyright violation. Given the state of the law with regard to indigenous intellectual property, I seriously doubt that the Hopi would be able to get any damages if they were to file a lawsuit against the Winters for misrepresentation of Hopi spiritual technologies. I doubt they'd even try. But it still is a matter of ethics & of respect.

If you feel that the Hopi people don't deserve being consulted about such use, even as they strongly request to be consulted, that's your opinion, which you've expressed. My opinion is that it's a mistake to err unknowingly (as I think the Winters probably did), but it's downright wrong to do it knowingly. In the marketplace of ideas, it's my right to say so. As it is Debbie's.

I wrote earlier, "To me, it's tantamount to copyright violation."

I realized, that's not anywhere near being a strong enough statement. "Copyright violation" is part of it, sure, but not the all of it. It's taking another people's most deeply held beliefs & understandings, without permission or discussion, & doing with them whatever one wants. For art, for aesthetics, whatever: it doesn't matter — to the person who thinks such theft is okay.

Interesting that Christianity & Islam were brought up. Both these world religions have shown themselves capable of dealing much more seriously than merely bringing lawsuits against people who used their spiritual technologies without understanding, without permission. At the same time, they both have histories of borrowing & adapting or stealing & subsuming other people's religious ideas sometimes, or of eradicating those ideas & the people who held them at other times. That's certainly been the case in the Americas.

I find it not just absurd, but offensive & ugly, to think that "I will take the symbols of your beliefs without permission, interpret them in whatever way seems good to me, then present them for my own fame & profit" is in anyway an honoring of the people one has stolen from.

No matter how pretty the product of my art looks to the "95% of the critical concensus who have practically called the book an American masterpiece."

(...Groupthink, did you say? Uh huh.)

"(...Groupthink, did you say? Uh huh.)"

Indeed Melissa. Groupthink is alive and well here. By your own admission you still have not seen nor engaged with the book physically, yet you continue on as if you've had a copy for ages. One of the aspects of group think is to argue for or against any work of art without even have had the experience of dealing with it directly. Hearing the report of others is not an acceptable substitute in any of the arts.

I politely requested yesterday (above) that six scene-specific points on alleged anachronisms be addressed. You took up the gauntlet and responded at length in two comments. Your focus? The sixth and last point only. You stood clear of the first five in an obvious attempt to keep the focus on only one of my contentions. Maybe Debbie and/or K.T. will address them, maybe they will not. If the latter, I've made my points and will now move on. For whatever disagreements I maintain with Debbie, I respect her. Her website here is linked to the sidebar of my own site. I pop in during the year from time to time to see what she is writing about. She penned a second review and has been involved in the discussions here for several days now.

I stated repeatedly that the use of the kachina dolls in this book was in the vein of positive energy. Debbie doesn't agree. You don't agree. You go off on a long tangent on using symbols without permission and paint this benihn use in teh worst possible light. You then rail agains past infractions by Christians and Muslims living in America. Yes I believe in freedom of expression and dramatic license, and no negative connotations implied here or anywhere else will impact that position.

I really do need to move on now. Perhaps at some future point we'll cross paths and share our beliefs and artistic taste. The review I wrote on this book was only one brief chapter of my Caldecott series, and I need now to focus on the other books. I've fallen way behind, and for much of this I have myself to blame of course. Debbie needs a break. You need a break. I must re-focus. Thank you and best wishes.

There may be some who will respond to what I say in this comment as "you didn't say that before" --- and they'd be right about some things, but what I say here isn't new thinking at all. I have a lot more notes on the book that did not get into my review. Here's my replies to Sam's 6 questions. I offer these replies as I would in a workshop or lecture or classroom. Some of what people have said here or at Reading While White will likely be part of the conversations that will take place at the Horn Book's Calling Caldecott blog if/when this book is discussed.

1. For some people, "In the beginning" evokes warm feelings with its obvious reference to the Bible. It is not that for me and for peoples who were oppressed and persecuted by Christians. Some Christians have seen "the light" of that persecution and step away from it.

2. The text does not say the woman painting is O'Keefe, but that is a painting she's widely known for. No doubt others painted it, too, but the way the painter is shown sure looks like the way that O'Keefe dressed. Could be another woman, for sure. Only Jeanette Winter knows what she was going for there.

3. The text does not say that the scientists were going into the Plaza but the next page definitely shows that is where they were going. I can't put images in comments, so will insert it above in the review.

4. The text is "Outside the laboratory, nobody knows they are there." I read it one way; Sam reads it another.

5. I'm not following Sam's objection or use of the word "experimentation" in quotes.

6. I believe the Winter's meant well by including kachinas but I see that use as a bad choice. We've had many exchanges here, and at RWW about that. Sam's insistence that I see that use as he sees it? Not gonna happen. The best I can do is say that the Winter's meant well, but I don't think they knew what they were doing.

"By your own admission you still have not seen nor engaged with the book physically, yet you continue on as if you've had a copy for ages."

Actually, Sam T., yesterday I purchased a copy on Kindle, and had read it before making the two comments above. And will read it again too, & spend more time with the pictures (yesterday was a busy day.)

I didn't feel "required" to address all your six objection, which you hadn't addressed to me in the first place.

"Groupthink" in my comment above was, of course, a reference to your continued reliance in argument to "95% of critics say this, why can't you agree with us?"

Mithridates,

Soon after my initial review in March, the hosts at All the Wonders added it to their page on THE SECRET PROJECT. Within a few hours, they had removed it. The host, Matthew Winner, submitted this comment. I'll put it all in italics to distinguish it from my own words here, and, I'll use bold text for what he said about the reaction the Winter's had when they saw that my critique was on the All the Wonders site:

Hi everyone. I want to apologize publicly here to anyone who was offended by our decision to include Debbie’s review of The Secret Project in our feature at All Wonders and then retract it later that day.

We feature one book each month in addition to our regular content, and the selected book is one that our team believes stands above the rest. We think of our features as an award from our team, and we honor the chosen book by compiling various forms of content that celebrate it. We even describe the feature to the artists involved as "a week-long celebration of your book." These words, we believe, enter us into a verbal agreement that we will shine a positive light on their work, and it is based upon this agreement that the publisher grants us permission to license their images, words, and behind-the-scenes content. I made a misstep, then, by surprising Jonah and Jeanette Winter and their publisher, Simon & Schuster, with a critique, and introducing an element of debate into the feature. After careful reconsideration of these factors, we decided to pull the post.

I know now that this series of events confused and offended a number of individuals. I am sorry for that. We (myself along with the team) had the best intentions, which was to offer a “second perspective” post from Debbie, who saw something that we did not see in our reads through the book. We consider critically all of the books that we include on our site, and we welcome discussions about how they are serving readers, but our features in particular are not designed for that purpose. They are designed to give children multiple entry points into what we believe to be special books.

Once we came to the decision to pull Debbie’s post, we immediately communicated to her via email that we would be removing her post for these reasons and gave her an open invitation to address American Indian representation in children’s books on our site or in the form of a Twitter chat. Though we are still waiting for an official response from Debbie, it is our sincere hope that she will choose to work with us in the future to raise awareness about misrepresentations of American Indians in children’s literature.

Our goal at All the Wonders is not to silence, but to raise the voices of authors, artists, bloggers, and critics in service of readers. I regret the way these events have unfolded, but I consider this an opportunity to learn from our mistakes and a renewal of our mission to build positive relationships with all of our colleagues.

Sincerely,

Matthew C. WinnerAll The Wonders co-founder

Post a Comment