TIMELINE

August 10, 2017

PEN Center USA announced finalists for its 2017 Literary Awards. John Smelcer's Stealing Indians is among the finalists in the young adult category.

August 11, 11:18 AM, 2017

On social media, people began to talk about his nomination when Marlon James posted the following on Facebook:

If you were at the Wilkes MFA, when I was, then you know full well the living con job that is John Smelcer. This is the man who at our class reading invented a language, claiming that it was an ancient Native American tongue, and he was its last speaker. So a few days ago PEN Center USA (PEN America) nominated his novel "Stealing Indians" in the category of Young Adult. Let's leave the title for another day. This 2016 book has a blurb from Chinua Achebe. Achebe died in 2013. This is the motherfucking fuckery we keep talking about. Why does this alway happen? Why do these people keep making the same stupid mistakes? You werent conned, you were fucking lazy. Seriously, the quotes all over his site from dead people didn't tip you off? The shadiness of his name? You couldn't have done one stinking google search? Nothing? Nothing at all? How can you claim to listen to us, when you keep making the SAME MISTAKES all the time, like the one you made the last 15 times we spoke to you. If this isn't rescinded, I'm done with PEN. Consider my membership over. Real talk.Kaylie Jones participated in that conversation (more on that below).

August 11, 12:40 PM, 2017

At its Facebook page, PEN Center USA posted this announcement:

PEN Center USA has become aware of concerns expressed by some within the literary community regarding the nomination of John Smelcer's STEALING INDIANS for the 2017 PEN Center USA Literary Award for YA. Our staff takes these concerns seriously and is investigating them further to determine an appropriate path forward in accordance with our mission to both celebrate literary merit and defend free expression for all.

August 11, 6:25 PM, 2017

Laurie Hertzel of the Star Tribune, published a brief article about the developing story: Marlon James, others join growing backlash against writer claiming American Indian heritage.

August 13, 2:37 PM, 2017

Rosebud Magazine's twitter account posted "Marlon James is wrong. Ahtna is a real language and a real culture. John Smelcer speaks Ahtna, has papers. ANYONE can easily check this out"

Smelcer is an editor at Rosebud Magazine. In his post to Facebook, Marlon did not deny the existence of Ahtna as a language or a culture. His post (see it above) was with respect to Smelcer's claims that he was the last speaker of a language he was presenting at Wilkes. The screen capture below was posted to Smelcer's FB wall at 3:06 PM on August 13:

There was also a second post with a link to an Ahtna 101 video channel, run by "Johnny Savage." Both of those Facebook posts have since been deleted and replaced with this:

On her Facebook page, Kaylie Jones posted a statement she provided to PEN USA. It says, in part,

The James Jones Fellowship submissions are read blind; the judges do not know the identities of the authors who submit. We learned from Smelcer's bio, once the announcement of his win was made, that he was a member of the Alaskan Ahtna Native American tribe. We were, of course, delighted to hear this.

It was not until 2005, when Smelcer was invited to give a reading and participate in the Wilkes University MFA Residency week, that our suspicions about his integrity were brought to the fore. He stated in his bio that he held a PhD from Oxford University. One of our faculty, herself a PhD who had access to an international database of all PhDs granted by universities worldwide, researched his claim and found that Smelcer did not hold a PhD from Oxford. He was immediately dismissed from the Wilkes faculty.

and

In 2015 the James Jones First Novel Fellowship committee voted unanimously to rescind his 2004 Award. We chose not to pursue legal action, as we simply do not possess the funds to do so.

This entire fiasco is a terrible stain on the reputation and integrity of the James Jones First Novel Fellowship, and regardless of the outcome of the PEN Awards controversy, I felt absolutely compelled to take a stand.

August 24, 2017

Writing for The Stranger (a weekly newspaper in Seattle), Rich Smith published Meet John Smelcer: Native American Literature's "Living Con Job." It is a deep dive into many of the claims Smelcer has made. Smith quotes from my posts about Smelcer. I was not interviewed for the article.

August 25, 2017

The Los Angeles Times published Writer's claims to native heritage are questioned after PEN Center USA names his book a finalist, written by Terese Mailhot.

August 29, 2017

On August 28, The Huffington Post published YA Author Accused of Lying About Credentials and his Native Heritage, by Claire Fallon.

Later that same day, Rich Smith at The Stranger wrote about PEN Center USA withdrawing Smelcer's book from consideration for its YA award: John Smelcer's Nomination for a PEN Award Gets Pulled, and More Details about His Past Emerge.

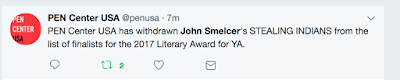

Here's a screen cap I made of PEN's announcement:

August 30, 2017

See Alison Flood article, John Smelcer dropped from YA award amid 'concerns' over integrity, published in The Guardian.

On its Facebook page, Raven Chronicles writes:

"Raven Chronicles worked with Smelcer in early 90s as our poetry editor for a short time. There became questions about his self-described heritage. These questions and about his adoption still haunt him. The entire matter is sad even given all the awful rationalization posted on his website. In the literary world fakery is only applauded when in a bestseller. Now he is finally getting all the notoriety he has always hungered for."

September 13, 2017

On August 30, Erin Somers, writing for Publishers Marketplace, published "Pen Center USA Withdraws Smelcer's Stealing Indians Amidst Claims of Fraud." It concludes with a statement from LeapfrogPress (Leapfrog published Stealing Indians). I am including the statement below, for those who do not have access to Publishers Marketplace.

"Leapfrog Press has had no communications from PEN regarding the withdrawal of this nomination, and has no information on the reason for the withdrawal, other than an emphatic statement from PEN that the author's heritage was not in question, and the equally emphatic statement that none of the writers making public accusations are speaking for PEN. Leapfrog has seen no evidence, and no writer or media outlet has been able to provide evidence, to support accusations being made on social and in print. Public charges made, such as that Leapfrog Press was created by this author for his own books, and that the Ahtna language is made-up 'gibberish,' can be debunked so quickly that they call into question all public statements from those individuals. Leapfrog Press does not condone any attack against any writer's ethnicity, or the mocking of Native American languages."

A note from AICL: At some point, Smelcer revised the homepage for his website. Prior to this, it had been a lengthy page of claims Smelcer made about famous people he worked with and edited, and book prizes he was nominated for. That page now consists of a single paragraph that includes none of the previous claims. Several other pages from his site are also gone, including the contact page that had "Johnny Savage" listed as his agent.

****

And below, some background:

January 27, 2008

I posted a brief note about Smelcer's The Trap. Within a few hours I heard from several people that Smelcer is not Native. I had taken him at his word (that he is Native) and was taken aback to learn that his claims of being Ahtna were not accurate. (Since then, I've written about him several times at my site. I've tried to be as clear as possible but the sheer depth and breadth of Smelcer's claims are, indeed, a rabbit hole. I've spent many hours trying to verify what he says about his collaborations with other writers. Here, you'll find a list of the posts that are the product of that research.

Feb 1, 2008

Roger Sutton, of Horn Book, posted White man speaks about Smelcer. On Oct 2, 2011, "Larry Vienneau" posted a comment, saying "If you are interested in the truth please visit ___ (the link no longer works). Vienneau is an illustrator who has illustrated for Smelcer's books. On October 11, 2011, "blackfeet 1954" submitted a comment about adoption rights. On October 16, 2011, "blackfeet1954" submitted another comment.

October 17-18, 2008

I was an invited speaker at the "American Indian Identity in Higher Education" Conference held at Michigan State University. Upon arriving and talking with Native professors there, I asked if anyone knew Smelcer. I learned he was already well-known in Native writer networks as making questionable claims about his identity. Some of the talks were taped and are online. In the video of my talk, I recount that 2007 encounter with the book, my calls to the Ahtna tribal office, a phone call from his father, and Smelcer's emails to me.

July 24, 2009

Diane Chen reviewed Smelcer's The Great Death. In her post, she recounts the background research she did on Smelcer. On October 17 at 1:03 AM and 1:11 PM, "blackfeet 1954" and "Edward Crowchild" submitted nearly identical comments.

December 4, 2010

Amy Bowlan posted to her blog at School Library Journal, pointing her readers to the American Indian Identity paper I delivered in 2008. Comments submitted on October 7, 2011 by "Crowfeather" (I am fascinated by your ability to self promote, your seeming endless options, and your belief that you speaks for all native peoples and cultures.)and October 21, 2011 by "E. Crowchild" (Ms Reese likes to think she speaks for many natives, but she really speaks for herself.) sound very much like Smelcer's writings on his Ethnicity page at his website ("In no way does Debbie Reese represent or speak for all Native Americans. She’s not even a spokesperson for her own tribe.").

January 8, 2015

I received an email from Kaylie Jones, daughter of James Jones, for whom a literary award is named. Smelcer had won the James Jones award in 2004 for Trapped. In subsequent phone calls with her, I learned that she wanted to rescind the award and had taken steps to remove his name from the list of people who received the award. Note there is a winner for 2003 and one for 2005.

Spring, 2016

Native colleagues began talking online about some of Smelcer's poems that were on the Kenyon Review's website. Soon after, the poems were removed. Here's a note from David Lynn, the editor:

June 18, 2016

Therese Mailhot, writing for Indian Country Today, published John Smelcer: Indian by Proxy.

July 24, 2016

AICL's review of Stealing Indians.

August 14, 2017

- For some time now I have been periodically checking to see if Smelcer has removed or acknowledged errors he's made in "Setting the Record Straight" -- a document he maintains at his website. Towards the end of it, he says many things about me that are not true.

________________________________

Note: Because of the nature of this discussion, AICL will not publish unsigned or anonymous comments.