Because of the work I do as an advocate for children's books that accurately reflect Native people, I am taking a moment to thank the Native writers who wrote books about her. I hope every school library in the country has them. If not, put an order in right away!

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

- Debbie on Social Media

- 2024 American Indian Literature Award Medal Acceptance Speeches

- Native Removals in 2025 by US Government

Thursday, January 16, 2025

Thank you, Native writers who gave us books about Secretary Deb Haaland!

Because of the work I do as an advocate for children's books that accurately reflect Native people, I am taking a moment to thank the Native writers who wrote books about her. I hope every school library in the country has them. If not, put an order in right away!

Monday, November 29, 2021

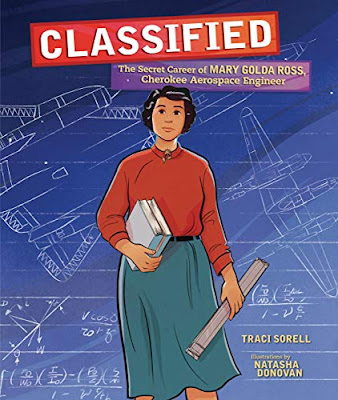

Highly Recommended! CLASSIFIED:THE SECRET CAREER OF MARY GOLDA ROSS, CHEROKEE AEROSPACE ENGINEER, by Traci Sorell and Natasha Donovan

Wednesday, May 12, 2021

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED! Charles Albert Bender: National Hall of Fame Pitcher

Biographies of Native sports figures have been few and far between, in my experience. Jim Thorpe and Tom Longboat are two that immediately come to mind. So it feels great to be able to recommend Kade Ferris' middle grade book about the Ojibwe man who invented a special pitch called the slider.

Charles Albert Bender: National Hall of Fame Pitcher is part of the new series, Minnesota Native American Lives, edited by Gwen Nell Westerman and Heid E. Erdrich. AICL has already reviewed two others, about Peggy Flanagan and Ella Cara Deloria.

Charles Bender was born near Brainerd, MN, in 1884. His mother Mary was an Ojibwe woman who cooked for a lumber company, and his father Albertus was a white (German American) lumberjack. After the trees were gone and the lumber company moved on, the family farmed on the White Earth reservation. One of the tasks that fell to Charles was picking up rocks in the field and throwing them out of the way of the plow. After a while, his aim was very good and his throwing arm was powerful. He credited this experience with the foundation of his success as a pitcher.

Charles and some of his siblings attended a boarding school in Pennsylvania for several years. He enjoyed his academic subjects there. When he was finally able to go home, he found living with his family intolerable. The crowded conditions and his father's brutality made him eager to leave again, this time for Carlisle Indian Industrial School. If you've read about Jim Thorpe's life and career, you'll remember that athletics were very important at Carlisle. Charles' talent for pitching caught the attention of Carlisle coach Glenn "Pop" Warner, and Warner eventually persuaded him to join the baseball team.

Reading both the bio of Ella Cara Deloria and this book may have you pondering life trajectories. Ella Deloria was a multi-talented person who turned to academics amid ambient racism and sexism. Charles Bender, biographer Ferris tells us, also had multiple strengths. A very good student, he was drawn into athletics as a young man, and that world is where he spent much of his adulthood. Like Jim Thorpe, Charles excelled at several sports. He came to love golf and was so good at trapshooting that, in his day, he was nearly as famous for his marksmanship as for his pitching.

After graduating from Carlisle, Charles set aside an opportunity to continue his studies, and went to pitch for a semi-pro team in Harrisburg, PA. A scout for the Philadelphia Athletics noticed Charles' exceptional pitching during an exhibition game against the Chicago Cubs, and told the now-legendary Athletics' manager, Connie Mack, about him. Ferris centers the high and low points of Charles' time in major league baseball, like any biographer writing about a sports figure. For example, he notes that Charles' pitching for the Athletics in the 1911 World Series was hailed as "one of the most impressive feats in baseball" -- "striking out twenty batters in twenty-six innings and only allowing one earned run average in the three games he pitched." The reader can relish hard-won victories along with Charles and his teammates, and feels the sting of set-backs and defeats. The book includes a table of stats for Charles Bender's major league career.

But Ferris also does not avoid the fact that, like many athletes who were not white, Charles endured racist micro-aggressions and even blatant aggression. There were the seemingly inevitable war whoops from "fans", being nicknamed "Chief" in the press against his firm objections, and sometimes worse. In 1907, he was even refused service and physically thrown out of an evidently whites-only soda shop in Washington DC when he ordered a soft drink. Ferris speculates that Charles did not let these situations "get him down," and he certainly did not let them define him.

The triumphs and tribulations of being an Ojibwe athlete and person in the world are likely to stand out for readers. I enjoyed the ways the author presents what major league baseball was like during its early years -- quite a contrast to today! I can't speak for other readers who are sports fans, but I was interested Charles Bender's life outside of his athletic career. The book mentions his oil paintings, gardening, and love of the natural world, but not (I had to look this up) the fact that he was married for about 50 years to the same woman. I don't see this as a flaw in the book so much as an indicator that this bio leaves the reader wanting to know more, and that's a good thing.

As with the other books in the Minnesota Native American Lives series, Tashia Hart's illustrations augment the text, sometimes poignantly. See how she signals that Charles was retiring -- hanging up his cleats -- on p. 37. At least one illustration includes a subtle nod to Ojibwe identity -- the floral design around the full-length portrait of Charles Bender in action, on p. 23.

The book includes the same "Extend Your Learning" pages that are part of the other books in this series -- an excellent resource for educators. I sure hope editors Gwen Nell Westerman and Heid E. Erdrich have more of these middle-grade biographies in the works about influential Indigenous people. You can express the same sentiment by buying these books and/or sharing them with students!

Thursday, March 25, 2021

Highly Recommended! PEGGY FLANAGAN: OGIMAA KWE, LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR

Most readers may not notice the strawberry or the flag, but Ojibwe families will, for sure! Hart's illustrations and Engleking's words are mirrors of their identity.

That, too, is a mirror of Native experiences in school. For far too long, Native children have been in classrooms where a teacher puts that myth forward, uncritically. I'm glad that's in there, and I hope it is the nudge teachers need to stop doing that!

She currently resides in Minnetonka and is isolating in Elklader, Iowa...

We need a biography of her, and of Sharice Davids, too. She's Ho-Chunk and was elected to Congress to represent Kansas, in 2019. Haaland was also elected that year, to represent New Mexico.

Wednesday, March 24, 2021

Recommended: Ella Cara Deloria, Dakota Language Protector

Friday, December 13, 2019

Recommended: SPOTTED TAIL by David Heska Wanbli Weiden

The book's four sections or chapters -- Early Years, Warrior, Family Life, and The Chief -- are followed by two pages that explain some Lakota customs, and 2 pages appropriately titled "A Short History of the Lakota People." (It's very short.)

This story of Spotted Tail's life opens with a description of his participation, as a boy, in a buffalo hunt. It ends with a brief account of his 1881 murder and its eventual repercussions for Indian law, and some paragraphs about his legacy.

In between, what stands out are Spotted Tail's efforts to understand and address the threat posed to his people, and to all Native peoples, by the ever-encroaching settler-colonizers. Weiden, who is Sicangu Lakota*, shows how his subject's perspective changed with his experiences, from young Lakota fighter to prisoner of the US government to caring father to negotiator for his people. He even briefly sent some of his children to the Carlisle Indian boarding school. (When he discovered during a visit there just how the school was "educating" Native children, he took them home again.)

A real strength of the book is the way Weiden connects certain aspects of Spotted Tail's life with ongoing issues for Native people -- such as the Lakota people's efforts to keep/recover the Black Hills. The long-lasting legal and political implications are simply but clearly explained.

One of the Lakota customs Weiden explains is naming, specifically his Nation's customs around receiving a "spirit name." At first I winced on seeing that; too many non-Native people love the idea of "Indian names" and want to appropriate them! But a careful reading assured me that, unlike some authors who talk about naming practices, Weiden provides context and limits for Lakota naming. In the main text, he explains the circumstances of Spotted Tail's naming. In "Lakota Customs" at the end, he notes that many cultures give children spiritual or religious names, and explains that in Lakota culture, naming is often accompanied by a giveaway. Most importantly, in my opinion, he shows subtly that a Lakota spirit name is not something just anyone can get. That's a healthy perspective on the matter. He invites readers to consider whether they "like the idea of having two names" -- much better than inviting someone to choose their own "Indian spirit name."

The combined efforts of artists Jim Yellowhawk (Itazipco Band, Cheyenne River Sioux) and Pat Kinsella (White) -- especially the many dramatic 2-page spreads -- make Spotted Tail visually striking. Yellowhawk's ledger-style art and Kinsella's bright photos and montages provide imaginative windows on what life might have looked and felt like for Spotted Tail, in his time, while connecting readers to the present-day Lakota Country landscape.

|

| Example of a 2-page mixed-media spread from Spotted Tail |

Discussion/reflection questions for readers are artfully incorporated into the illustrations, and interspersed throughout the book: "Do you think the government should apologize for terrible events that happened long ago?" "How would you feel if the government made you leave your home?" "What do you think it means to be wealthy?" The questions bring "added value" to the text, and adults who share or recommend the book may get good conversations started by asking young people to respond to them.

A few times when I was reading, it felt evident that Weiden is writing for a non-Lakota, non-Native audience -- for instance, he says, "If you are lucky enough to visit the Lakota Nation ..." But at no point did I have the feeling that he is "othering" anyone.

One wish for this and future biographies of historical Indigenous heroes:

Authors, please provide your sources. That allows your readers to follow your research trail, and become researchers themselves. [Edited 12/14/19 to add: Publishers, also take note -- help authors fit those sources into the finished work!]

[*Edited 2/25/2020 in response to a comment from Janessa: I apologize to the author and to readers for somehow omitting the fact that David Heska Wanbli Weiden is Sigangu Lakota. I have added it above. AICL remains committed to being clear about the tribal nation of Native book creators. Thanks for alerting us, Janessa.]

Sunday, December 02, 2018

Recommended: UNPRESIDENTED: A BIOGRAPHY OF DONALD TRUMP by Martha Brockenbrough

In Who Was George Washington? (one of the books in the very popular "Who Was" series published by Penguin), we read that when he was young, George Washington worked as a surveyor--someone who measures and marks property boundaries--to make money. It was "a rough life" in the "wilderness," sleeping on the ground, cooking over open fires, and, he had to "steer clear of hostile bands of Indians" (page 18). That book came out in 2009. Many people in children's literature think that Russell Freeman wrote excellent nonfiction for kids, but his writing was biased, too. In his biography of Abraham Lincoln, he wrote that Lincoln's father was "shot dead by hostile Indians in 1786, while planting a field of corn in the Kentucky wilderness" (p. 7). Titled Lincoln: A Photobiography, it won the Newbery Medal in 1988. I hope that a book that has bias like that in it would not be selected, today, for that medal.

Was Washington racist? What about Lincoln? And--are the authors of those books racist? The point: there's a lot to consider in how someone writes about a president.

Let's turn now to Martha Brockenbrough's Unpresidented: A Biography of Donald Trump, due out on December 4th from Feiwel and Friends. Anybody who has followed the news about the current president of the US knows that he's said a great many racist and sexist things. Brockenbrough doesn't shy away from any of that. I'm glad it is all here, documented, for young adults (the book is marketed for kids from age 12-17). I'm also glad that she's included information about Native people.

On page 98 she provides an account of trump's (I do not use a capital letter for his name) 1993 testimony at a hearing in Congress, at the House Natural Resources Subcommittee on Native American Affairs. She quotes him saying that "they don't look like Indians to me..." He was talking about Native people of tribal nations in Connecticut who had casinos that hurt "little guys" like him. At the time, trump was trying to make a deal with the Agua Caliente Band of Cahuilla Indians.

A few pages later, Brockenbrough provides readers with the name of another tribal nation. In 2004, the Twenty-Nine Palms Band of Mission Indians ended their contract with trump's hotel and casino company, because his company was in financial trouble.

It is terrific to see Brockenbrough being tribally specific. By naming these nations, she is pushing back on a widespread ignorance in the US. Too many people use the word "Indians." And it often leads people to think of Native peoples in stereotypical ways.

Another good point of Unpresidented is information on page 100, about tribal membership. Succinctly, Brockenbrough writes that tribal nations make determinations about their citizens. What they look like doesn't matter.

Oh! Another thing to note is the part about arrowheads! It tells us a lot about the trump family and its values. I recommend Unpresidented and welcome your comments if you read it. And--kudos to Brockenbrough for writing this book! Reading the news every day is tough on my psyche. Spending the time necessary to write this very comprehensive and in-depth book must have taken a toll on her.

Friday, November 09, 2018

Native Trailblazers, or In Search of “500 Brave Native Americans”

- Native Athletes in Action: Revised Edition (2016) (Review of 2012 edition)

- Native Men of Courage: Revised Edition (2016)

- Native Defenders of the Environment (2011) (Published before Standing Rock, it profiles some folks who later became NoDAPL water protectors in 2016-2017.)

- Native Musicians in the Groove (2009)

-- Jean Mendoza

Tuesday, September 25, 2018

Recommended! Art Coulson's UNSTOPPABLE: HOW JIM THORPE AND THE CARLISLE INDIAN SCHOOL FOOTBALL TEAM DEFEATED ARMY

Tuesday, November 28, 2017

Highly Recommended: THE WATER WALKER written and illustrated by Joanne Robertson

Joanne Robertson's book is one I'm happy to recommend.

Robertson's The Water Walker, published in 2017 by Second Story Press, is about Josephine Mandamin. Here's a photo of the two women, at a recent event promoting the book:

|

| Photo source is Anishinabek News: goo.gl/LwBpvU |

The story of a determined Ojibwe Grandmother (Nokomis) Josephine Mandamin and her great love for Nibi (water). Nokomis walks to raise awareness of our need to protect Nibi for future generations, and for all life on the planet. She, along with other women, men, and youth, have walked around all the Great Lakes from the four salt waters, or oceans, to Lake Superior. The walks are full of challenges, and by her example Josephine challenges us all to take up our responsibility to protect our water, the giver of life, and to protect our planet for all generations.Robertson turned Mandamin's work into an engaging story that invites children to learn about her activism. Told from the point of view of a child talking about her grandmother, Nokomis, we read about how Nokomis gives thanks, every day, for water.

While she is thankful for water, she doesn't yet have the awareness of what might happen to it. One day, an ogimaa (Ojibwe for leader or chief) told her that water is at risk. He asked her, "What are you going to do about it?" Looking around, she understood what the ogimaa meant. Water was being wasted and polluted by people who didn't seem to understand the ramifications of their treatment of life-giving water. Weeks passed as his words and her observations weighed on her. Then one night she had a dream. The next day, she put a plan into action.

See that? She called her sister, and kwewok niichiis (women friends). I'm not Ojibwe, but my heart swells seeing those Ojibwe words in this book! I see them all the time from Ojibwe friends and colleagues on social media. And clearly, these women are in a modern day kitchen. I love that, too. This story is centered in the present day. None of that silly or romantic nonsense in this book! That's a huge plus, too.

The action they took? Walking, with Nokomis at the head of the line, carrying a pail of water and a Migizi Staff.

They walked each spring, for seven years. That's serious and hard work--made accessible to kids by sneakers. The kwewok niichiis all wore sneakers as they walked. Every spring, they'd set out again. They started in 2003, walking around the Great Lakes and the St. Lawrence River. Sneakers wear out, as kids know. As they read (or as they're read to) The Water Walker, they'll enjoy the pages where the sneakers appear in text or illustration.

As they walked, they prayed and sang and "left semaa in every lake, river, stream, and puddle they met." I'm pointing out that Robertson says, simply, that they left semaa (sacred tobacco) as they walked. It is a significant action, but Robertson doesn't give details. I really appreciate that! Some things need not be shared with readers. In an #OwnVoices story, we know what to--and what not to--disclose.

In the next pages, we learn that Nokomis spoke to a lot of people about the walking. She was on TV, in the newspapers, on the radio, and in videos.

In 2010, women of other nations joined Nokomis and her kwewok niichiis. They brought water from the oceans. The Water Walker ends with a page much like one from early in the book, where Nokomis is outside giving thanks. The last words in the story part of the book are the ones in the question the ogimaa had asked Nokomis in 2003. This time, though, the words are directed at the reader. What are we going to do about what his happening to water?

On the final page, there's a glossary and pronunciation guide of the Ojibwe words used in the story, and there's additional information about Josephine Mandamin. Readers are invited to write to her, telling them what they're doing to protect water.

The Water Walker is an extraordinary book. I highly recommend it and hope that Second Story gives us more like it.

Thursday, March 31, 2016

Debbie--have you seen S.D. Nelson's SITTING BULL: LAKOTA WARRIOR AND DEFENDER OF HIS PEOPLE

I'm critical of books wherein the writer has invented dialogue for a real person. As a scholar in children's literature who works very hard to help others see biased, stereotypical, inaccurate, romantic and derogatory depictions of Native peoples in children's books, invented dialogue looms large for me.

In short: I need to know if there is evidence or documentation that the person actually said those words. This concern holds, whether the writer is Native or not.

In Nelson's Sitting Bull, the entire text is invented dialogue--and invented thoughts.

It is constructed as a first person biography. It is presented to us as if Sitting Bull is telling us his life story, after he's been killed. Along the way, we have some dialogue, but mostly we have what Nelson imagines Sitting Bull to have thought.

On February 1, 2016 in The Stories in Between, Julie Danielson wrote:

Increasingly, today’s readers also want to see dialogue attribution in the back matter of biographies. That’s because invented dialogue is still a touchy subject. You have those who think that it has no place and that any sort of made-up dialogue puts the biography squarely in the category of historical fiction. Then you have those who think such dialogue is acceptable, helps bring the story to life, and can still be considered nonfiction. In 2014, Betsy Bird wrote here about her changing feelings on the subject (“In general I stand by my anti-faux dialogue stance but recently I’ve been cajoled into softening, if not abandoning, my position”), which made me nod my head a lot.

Here’s where I (and many others) draw the line: if a biographer invents dialogue or shifts around facts in any sort of way, they need to come clean about this in the back matter. A great example of this is Greg Pizzoli’s Tricky Vic: The Impossibly True Story of the Man Who Sold the Eiffel Tower, the story of con artist Robert Miller, published last year and named a Kirkus Best Book of 2015. There’s a line in the starred review of the book that states: “The truth behind Miller’s exploits is often difficult to discern, and Pizzoli notes the research challenges in an afterword.”"Come clean" is, perhaps, a loaded way to characterize what Danielson is calling for, but I think it is an important call. I want to know what Nelson made up.

Clearly, this is not a hard and fast rule. If it was, Sitting Bull would not have been selected as an Honor Book by the American Indian Library Association. And--this isn't the first time the field of children's literature has looked critically at invented dialogue. Myra Zarnowski's chapter, Intermingling fact and Fiction, published in 2001 in The Best in Children's Nonfiction, has a good overview.

If I do an in-depth look at Sitting Bull, I'll be back. For now, though, I am not comfortable recommending it, and I may revisit what I said about his Buffalo Bird Girl when I wrote about it, back in 2013. It, too, is a biography.

I anticipate questions from readers who wonder if S.D. Nelson ought to get a pass on invented dialogue because he is Lakota. My question is: did he work with any of Sitting Bull's descendants as he wrote the story? Did any of them read the manuscript? If they did, and they found it acceptable, I'd love to see that in the book. On the cover, in fact! If I do hear anything like that, I'll be back to update this post.

Thursday, October 23, 2014

Sebastian Robertson's ROCK & ROLL HIGHWAY: THE ROBBIE ROBERTSON STORY

Thanks to this book, I've had the opportunity to learn a lot more about Robertson. Released this year (2014) by Henry Holt, the biography is written by Sebastian Robertson (yeah, Robbie's son). The illustrations by Adam Gustavson are terrific.

Robertson is Mohawk.

The second page of Rock and Roll Highway is titled "We Are the People of the Longhouse." There, we learn that his given name is Jaime Royal Robertson. His mother is Mohawk; his father is Jewish.

Allow me to dwell on the title for that page... "We Are the People of the Longhouse." That is so cool... so very cool... Why? Because this book is published by a major publisher, which means lots of libraries are likely to get it, and lots of kids--Mohawk ones, too!--are going to read that title. And look at young Robbie on the cover. Sitting on a car. Wearing a tie. The potential for this book to push back on stereotypes of Native people is spectacular!

In the summers, Robertson and his mom went to the Six Nations Indian Reservation where his mom grew up (I'm guessing that "Indian Reservation" was added to Six Nations because the former is more familiar to US readers, but I see that decision as a missed opportunity to increase what kids know about First Nations). There were lots of relatives at Six Nations, and lots of gatherings, too, where elders told stories. The young Robbie liked those stories and told his mom that one day, he wanted to be a storyteller, too.

That life--as a storyteller who tells with music--is wonderfully presented in Rock and Roll Highway. Introduce students to Robertson using this bio and his music. Make sure you have the CDs specific to his Mohawk identity. The first one is Music for Native Americans. Ulali, one of my favorite groups, is part of that CD. Check out this video from 2010. In it, Robertson and Ulali are on stage together (Ulali's song, Mahk Jchi, is one of my all time favorites. It starts at the 4:39 mark in this video):

The second album is Contact from the Underworld of Redboy. Get it, too.

Back to the book: Ronnie Hawkins. Bob Dylan. They figure prominently in Robertson's life. The closing page has terrific photographs of Robertson as a young child, a teen, and a dad, too.

Teachers are gonna love the pages titled "An Interview with My Dad, Robbie Robertson" in which Sebastian tells readers to interview their own parents. That page shows a post card Robertson sent to his mother while he was on the road. Things like post cards carry a good deal of family history. I pore over the ones I have--that my parents and grandparents sent to each other.

Deeply satisfied with Rock and Roll Highway: The Robbie Robertson Story, I highly recommend it.

Thursday, September 11, 2014

Was Paul Goble adopted into the Yakima and Sioux tribes?

For years, I've read that he was adopted by Chief Edgar Red Cloud. Here's an example from the World Wisdom website:

Paul Goble was adopted into the Yakima and Sioux tribes (with the name "Wakinyan Chikala," Little Thunder) by Chief Edgar Red Cloud.I've been skeptical of such statements and have started some research into that statement. I kind of doubt he was adopted into either one. Maybe Chief Edgar Red Cloud adopted him into his own Lakota family, but I doubt it was an adoption into the nation itself, wherein Goble's name was put down on the tribal census. The Oglala Lakota tribal constitution says members are those who are born to a member of the tribe.

The Yakima and Sioux are two distinct nations, by the way, and using both in that sentence tells us that the person who wrote it doesn't understand that they are two different nations.

His interest in Native Americans was so deep and genuine that he was adopted into the Yakama (Yakima) tribe by Chief Alba Shawaway and into the Sioux tribe by Chief Edgar Red Cloud.

Call me Swift Eagle. That's the name Edgar Red Cloud gave me during the 1973 basketball clinic that Bill Bradley and I conducted at the Pine Ridge Reservation in South Dakota. Edgar, the grandson of the famous chief Red Cloud, said I resembled an eagle as I swooped around the court with my arms outstretched, always looking to steal the ball. Swift Eagle. Oknahkoh Wamblee. the name sounded like wings beating the air.In the next paragraph, Jackson writes that Edgar Red Cloud gave Bill Bradley a name, too: Tall Elk.

But let's get back to Goble. I haven't found anything he's written himself that says he was adopted. Here's the dedication in his Adopted by the Eagles:

See that? He says he was given a Lakota name and called son by Chief Edgar Red Cloud, but Goble doesn't say he was adopted. He doesn't say anything about it in an interview at the Wisdom Tales website.* And he doesn't say anything about it in his autobiography, Hau Kola-Hello Friend published by Richard C. Owen Publishers, Inc. in 1994.

So... what is the source of information that says he was adopted? I'll keep looking. If you find something, do let me know.

Why it matters: Having his work cloaked with an adoption story suggests that he's got an insider perspective. As my post on The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses indicates, I find his work problematic, and so do Doris Seale, a librarian who is Santee, Cree, and Abenaki, and Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, an American Indian Studies professor who is Crow Creek Sioux. At the bottom of that post, you'll see a link to a post where I quote them. That post is About Paul Goble.

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

NATIVE WRITERS: VOICES OF POWER, by Kim Sigafus and Lyle Ernst

And here's an excerpt from the Introduction that I do not remember seeing before in a book meant for young readers:

There have been entirely too many falsehoods and myths written about the Native people of the United States and Canada. The depiction of Native people depends entirely on the writer's perspective. For example, a 1704 French and Indian raid on colonial settlers in the village of Deerfield, Massachusetts, was described as a massacre, whereas the annihilation of a village of sleeping Cheyenne Indians in 1864 was celebrated as a victory over "hostiles." Both are examples of the European American historical perspective, which has also been prevalent in movies, making Hollywood one of the biggest sources of distorted facts and stereotypes about Indians.

Teachers and librarians who use this book to do author studies... make sure you spend time with that intro! If you're into contests, challenges, or research investigations, you might ask students to look for examples of biased language.

Those of you familiar with Louise Erdrich and Sherman Alexie will recognize their photos on the cover. There is a chapter for both of them. I'm sure you've got their books, but you ought to have books by the other others, too. They are:

N. Scott Momaday, Kiowa and Cherokee

Marilyn Dumont, Cree and Metis

Tomson Highway, Cree

Joseph Bruchac, Abenaki

Maria Campbell, Metis

Nicola Campbell, Interior Salish of Nle7Kepmx and Msilx/Metis

Tim Tingle, Choctaw

For each author, there's several pages of biographical information, followed by a list of "Selected Works" and Awards. The works range from children's books to those for adult readers, but the audience isn't included, so you'll want to make sure you do a bit of research before ordering to make sure the book will work for your classroom or library. Though Native Writers is what is called "a slim volume" (just over 90 pages), it is packed with info. I highly recommend it, but don't assume it is complete... To the authors it includes, I'd add Cynthia Leitich Smith and Richard Van Camp. Both are at the very top of my lists.

Order it directly from 7th Generation.

Saturday, February 23, 2013

BUFFALO BIRD GIRL: A HIDATSA STORY, by S.D. Nelson

The subject of most biographies of Native women are Pocahontas and Sacajawea. I did a search of the Comprehensive Children's Literature Database to get a rough sense of how many books there are about each one. I limited the search to those published between 2000 and now. I got 188 on Pocahontas, and 192 on Sacagawea. Quite a lot, don't you think? Some critics say those two women are heralded by those who seek to celebrate figures in U.S. history because they helped Europeans. Some say they were diplomats; others say they were traitors.

My point in sharing those publication numbers is to say that I think publishers would do well to publish biographies of other Native women!

With S. D. Nelson's Buffalo Bird Girl: A Hidatsa Story, Abrams has scored a big win. It is racking up starred reviews by the mainstream review journals and by those who look more critically at the portrayals of American Indians. It is, for example, on the Cooperative Center for Children's Books CHOICES 2013 list.

Nelson's art invites the reader to pick up the book. Once inside, there's a mix of his art and photographs of Hidatsa people. The back matter provides a timeline that teachers will find helpful when using the book in the classroom. With the Common Core thrust upon them, this biography will surely get lot of use in classrooms.

I agree with the praise the book is receiving, but have one quibble. I wish that the book cover and text featured her Hidatsa name, Waheenee, which means Buffalo Bird Woman, instead of "Buffalo Bird Girl." I'm guessing the change from woman to girl was a strategy to help young readers identify with Waheenee as a girl, but I think Nelson's illustrations make that point quite well.

Some background

Nelson tells us that his source for this biography is Waheenee: An Indian Girl's Story; Told by Herself to Gilbert L. Wilson. Wilson's book was published in 1921.

Scholars in American Indian Studies and American Indian Literatures point out that the audience for these early books was not a Native one. As evidence, we point to text in the books, where the author is speaking directly to the reader. Consider, for example, Wilson's Myths of the Red Children published in 1907. In the Foreword, Wilson wrote that fairy tales from Europe were delightful, but that with Myths of the Red Children, America's "little reading folk" could develop "a kindly feeling for a noble but vanishing race" (p. vi). I think it is fair to say he was not thinking of Native children as readers of Myths of the Red Children.

Take note, too, of Wilson's use of "vanishing race." Wilson was part of the research efforts of the late 1800s and early 1900s that sought to document Native cultures before we died out. A major problem with that research effort is that many of the researchers did their work largely unaware of their own perspective, which is an outsiders perspective. Many did not understanding much of what they observed. A year after Myths of the Red Children was published, Wilson began his work with the Hidatsa people.

One outcome of that work was Waheenee. Like Myths of the Red Children, it was written for a child audience. Its final pages (beginning on page 183), speak directly to that young reader:

Young Americans who wish to grow up strong and healthy should live much out of doors; and there is no pleasanter way to do this than in an Indian camp. Such a camp you can make yourself, in your back yard or an empty lot or in a neighboring wood.Following that passage are instructions for making a pole hunting lodge and several pages of recipes. I think it fair to say that Wilson was keen on playing Indian.

Nelson is wise not to echo Wilson on that point. His careful use of Wilson's material is important in other ways, too.

Buffalo Bird Woman was born in 1839 and died in 1932. She lived through a lot of changes. The Hidatsa were part of the Fort Laramie Treaty of 1851. Subsequent violations of the treaty resulted in a huge loss of their land. During her lifetime, they were moved to a reservation. There were several devastating smallpox epidemics.

Of those significant events, only smallpox is included in Wilson's book. On page 9 of his book, Wilson says: "Then smallpox came." We all know that smallpox came from Europeans, but that information isn't provided anywhere in Wilson's book. In his picture book, Nelson does indicate the source for smallpox (p. 3):

It arrived with the coming of the white men. They did not bring the sickness on purpose, but Indians could not fight off this disease--they had no immunity to the dreaded evil spirit.During Waheenee's lifetime, her people experienced tremendous loss of land and were moved onto a reservation, but these things aren't included in Wilson's book. When the word 'enemy' appears in the book, it is used only to describe other tribes. Doesn't that strike you as curious? Biased, perhaps? It seems to me that Wilson wanted his readers (remember, this book was written for white children) to develop a viewpoint of Indians as aggressors.

Nelson talks about enemy tribes, too, but doesn't leave out reservations. On page 39 of his Buffalo Bird Girl, Nelson (in Buffalo Woman's voice) writes:

Like-a-Fishhook is gone now. There are no buffalo left to hunt, and the fur trade ended long ago. The government of the United States said my people had to move from our village. They promised to provide rations of food and clothing if we lived on a reservation. The government built roads, schools, and churches. They told us that our children had to learn to live the white man's way. So we Hidatsa, as well as the Mandan and Arikara people, gave up our round earth lodges and began living in square cabins on the Fort Berthold Indian Reservation.

I would have loved to see one more page about the Hidatsa, Mandan, and Arikara people... In the "Today and the Future" section of the Author's Note, Wilson writes this:

The Hidatsa people are still here, as are the Mandan and the Arikara. They remain one sovereign nation. Each member of the nation has the same freedoms as every citizen of the United States. Like all other human beings, they face the many challenges of a rapidly changing world. Today they govern themselves with self-determination. Their words and actions give shape to their lives and hope for their children.

I want teachers who use the book to put that information front and center of their use of Buffalo Bird Girl. Introduce students to the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation website. Teach the book by teaching children about Waheenee's people---as they are today. Teach them what sovereign nation means! Show them the pictures on the site! And while you're at it, teach them about Nelson's tribe, too. Visit the website of the Standing Rock Sioux Nation!

We need more books like this one, by authors like S.D. Nelson. Thanks, Mr. Nelson, and you, too, Abrams, for Buffalo Bird Girl.

Friday, January 23, 2009

Initial Thoughts: Capaldi's A BOY NAMED BECKONING: THE TRUE STORY OF DR. CARLOS MONTEZUMA, NATIVE AMERICAN HERO

"Montezuma would later reveal other, more complete versions of his life through interviews, newspaper and magazine articles, speeches, and letters--all of which have been saved in various libraries in museums throughout the United States. These documents were my source for Dr. Montezuma's own words, which I interwove into the original letter to more fully present the doctor's life. I have made every effort to be true to the original sources and have only added brief phrases to make the text flow smoothly."Hmm... I'm not sure about that... Combining his words from various places to "more fully present" his life story. Those details would definitely have been fine if they'd been part of the information she provides, but, presenting them as if they're part of the letter he wrote, the words he chose to share about who he is? That doesn't feel right.

Information provided on page 4, left side of the page reads:

"The Yavapai Indians have lived in central and western Arizona for centuries. In the days that they roamed the deserts of the Southwest, the men were mainly hunters and gatherers and the women were known for their intricate woven baskets."

They "roamed" the deserts? I bristle at the use of that word. Indians roam. Just like the deer and the antelope in the song Home on the Range... " Did the pioneers or the cowboys roam, too?

Curious, I did a few searches using Google:

On the web---

- Search phrase: "Pioneers roamed": 129 hits

- Search phrase: "Cowboys roamed": 938 hits

- Search phrase: "Indians roamed": 9,910 hits

I repeated the search in Google books---

- Pioneers roamed: 23 hits

- Cowboys roamed: 135

- Indians roamed: 688 hits

Interesting numbers, eh? Given the ubiquitous image of roaming Indians, it is not surprising that Capaldi did it, too. But that doesn't make it ok.

And the illustrations that accompany the text on that page?

Above the text that says "roamed" is a black and white photograph that "shows a Yavapai family in the 1880s." The boy in the photograph is wearing jeans and a long sleeve shirt. The girls and women are wearing what look like calico dresses. Capaldi's illustration, which spans the double-paged spread, depicts a barefoot man and boy wearing breechclouts. The man carries a spear. To my eye, Capaldi's illustration of the man screams stone-age caveman.

Overlaying the illustration is the opening paragraphs of the letter that Capaldi uses as the frame to tell this story. But again, are these the words he actually wrote in that letter?

Ah, yes, some of you may say "HE used the word "roamed" in his letter..." In fact, he may have. Some Native people adopt(ed) words use(d) by white writers, but because of what Capaldi said in her Author's Note, we don't know if "roamed" is Montezuma's word or hers.

I'm searching for a copy of that letter. When I find it, I'll be able to make some comparisons.

To be continued...

_________________

Update: March 14, 2009

Capaldi's book was discussed two other times:

Monday, January 28

Sunday, Feb 1, 2009