______________________________

I've received several questions about Indeh: A Story of the Apache Wars by Ethan Hawke and Greg Ruth.

Published by Hachette Book Group in 2016, this graphic novel wasn't published for, or marketed to, children or young adults. That said, we know that teens read a lot of things that wasn't necessarily meant for them. There are awards, too (like the American Library Association's Alex Award) for books regarded as "crossover" ones--which cross over from the adult to the teen market.

Teachers and librarians are asking if Indeh can be used in high school classrooms. Short answer? No.

Generally, reviews on American Indians in Children's Literature are specific to accuracy of content which, in my view, makes them suitable for teachers to use when they develop lessons or select books to read aloud in their classrooms.

The questions I'm getting suggest that teachers wonder if there's enough accuracy in Indeh to use it to teach about the Apache wars. It may also be coming from teachers who know that graphic novels are a hit with teens and that Indeh may work well with teens who are reluctant readers.

Again--my answer is no. It isn't accurate (more on that, later). There's another interesting factor to consider.

Hawke's Use of Geronimo's Words

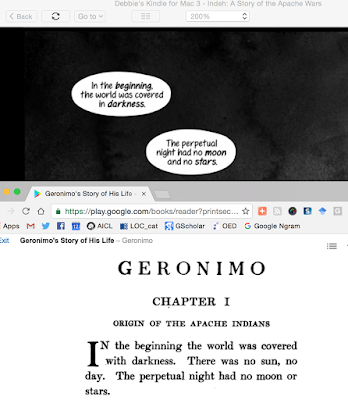

As I started reading Indeh, I pulled out the resources I use when doing book reviews. I had Indeh in one window (I use a Kindle app on my computer) and in another window, I had a copy of Geronimo's Story of His Life which was "taken down and edited by S. M. Barrett." He was the Superintendent of Education in Lawton, Oklahoma and the contents of this book were told to him by Geronimo. The first pages in it are devoted to copies of letters that went back and forth between several people involved in authorizing Geronimo to tell his story. It was published in 1906 by Duffield & Company in New York.

Right away, I hit the pause button in my reading. Here's a screen cap comparing the opening lines of Hawke's book (on top), and Barrett's (on the bottom):

This paraphrasing happens in several places in the book. (Note: In response to those who asked to see the other examples, I've added three, at the bottom of the post.) In the afterword, Hawke tells us that Once They Moved Like the Wind by David Roberts inspired him to write Indeh. Though Hawke includes Barrett's book in the "for further reading" section, I think he should have written about Barrett's book in that afterword because of passages like that shown above. This happens later, too. A big deal? Or not?

I'm noting it because--in the afterword--Hawke talks about appropriation (p. 228):

The Apache Wars are a vital part of our American history that needs to be told in a way that honestly appreciates and integrates, rather than appropriates, Native American history.Hawke's use of the word is odd. What does he mean? I could say that, in using Barrett like he did, he's appropriating Geronimo's words. Is that a form of appropriation?

That said, my primary concern is with the accuracy. First, let's look at what Hawke sets out to do with Indeh.

Hawke's Intent

In his Afterword, Hawke recounts a story from his childhood. His parents had divorced, and his dad took him on a camping trip. They were somewhere near the Arizona/New Mexico border when (p. 227):

An old man waved us down from the center of the two-lane road--the only living thing as far as my eyes could see. I heard him say in an unfamiliar cadence, "You are not supposed to be here."The old man told them they're lucky it was him that found them (he looked directly at 8-year-old Hawke when he said that, and that old man's eyes stayed with Hawke). Hawke's dad turned the car around. Hawke asked his dad what happened.

My father explained what an Indian reservation was, what an Apache was, how we really shouldn't have been there at all, and how lucky he was not to have gotten his ass kicked.Hawke asked what the old man meant about them being lucky he's the one who had found them.

My father told me, "Many of the Indians are very angry. And they damn well should be."Hawke asks if they're mad at him (he doesn't tell us if his dad responded to that question). From then on, he started buying and reading books about Geronimo, Cochise, Victorio, and Lozen. From those books, he says he saw that

...the cowboy movies I'd always loved took on a different hue. They were full of lies. Those gunfights weren't cool, heroic frays--they were slaughters.All that made me pause. Hawke was born in 1970. So, he was out there on that two-lane road in 1978. My guess is that they were on either the Fort Apache Reservation, or, on the San Carlos Reservation. Though the reservations are under the jurisdiction of their respective governments, they aren't closed to others. There are times when we close off the roads to outsiders, but that doesn't sound like what happened to Hawke. Who was that old guy?! The "should not have been there" portion of Hawke's story sounds... dramatic. I'm not saying it didn't happen; I'm just wondering who the old guy was. Part of me thinks Hawke and his dad got punked! On the other hand, it is possible that the man was home after having spent time with the Native activists doing activist work at Alcatraz in 1969, at the Bureau of Indian Affairs offices in Washington DC in 1972, or Wounded Knee in 1973.

Anyway, Hawke goes on to talk about his adulthood... working in Alaska with Native actors, and watching Smoke Signals and Powwow Highway, and reading one of Sherman Alexie's books. Hawke writes that (p. 228):

The story [of the Apache wars] needs to be told again and again until the names of Geronimo and Cochise are as familiar to young American ears as Washington and Lincoln.Can I do a "well, actually" here? I think Geronimo IS one of names Americans -- young and old -- are familiar with. Do you remember that "Geronimo" was the code name the US military used for Bin Laden? Do your kids yell "Geronimo!" when they are doing something they think is courageous?

He, I think, is far more visible than Hawke suggests.

I did a search in WorldCat, using Geronimo, and found 26,964 items in the nonfiction category, which is a lot more than the 9,028 items for Sitting Bull and the 4,669 items for Crazy Horse. (Note: There are 413,469 items for Washington, and 80,501 items for Lincoln.) In its We Shall Remain series (consisting of 5 episodes), PBS did an entire segment on Geronimo. There are more movies with or about Geronimo than any other Native person. I think he's the most well-known Native person.

Hawke's afterword suggests that his goal, with Indeh, is to tell a story that counters the biased stories and movies he saw as a child. Does he succeed?

Short answer: No. In plain text below are summaries from Indeh. My comments are in italics.

Hawke Makes Serious Errors

Part One of Hawke's book is called "A Blessing and a Curse." The story opens with Cochise recounting the Apache creation story to his son, Naiches and to Goyahkla (who will later be known by the name, Geronimo), both of whom are young boys. The blessing and curse is Cochise's power to see the future. Cochise tells the boys that their lives will be hard... and then there's an abrupt shift forward in time, to Goyahkla, seventeen years later. He sits in the midst of a massacre. While he and most of the other men were away, trading, Mexican soldiers attacked their camp. Amongst the dead are Goyahkla's mother, his wife (Alope), and their three children. Naiches--who is narrating the story--tells him they can't stay to bury the dead, but Goyahkla doesn't listen to Naiches.

Debbie's comments: Hawke's telling suggests that Naiches is in charge. Barrett says that it is Mangus-Colorado who was in charge and that it was he who said that they had to leave the dead on the field, unburied. Roberts (Hawke's primary source) says it was Mangas. The date of that massacre, Roberts writes, was March 5, 1851.

In his grief, he remembers when he went to Alope's father to ask if he could marry her. Alope's father asked him for "one hundred ponies" (p. 11). One hundred ponies sounds cool, but I think the "one hundred" is Hawk's flourish. Historians note that Alope's father asked for ponies, but nobody says "one hundred". A small point of inaccuracy? No. When there's such a body of misinformation about someone, it does nobody any good to add to that body of misinformation.

Goyahkla carries Alope's body to their wickiup (in Indeh, the word Hawke uses is "wikiup" which is incorrect). He remembers telling his son a story, and carries his son's body to the wickiup. He remembers his daughter's first menstrual period, and carries her body to the wickiup, too. He lights the wickiup on fire.

Debbie's comments: That is not accurate. They left the bodies and returned to their settlement. There, Goyahkla burned their tipi and all their belongings. That is when he "vowed vengeance upon the Mexican troopers who had wronged me" (Barrett, p. 76).

Then, Hawke tells us, an eagle appears on top of the wickiup. It tells him that bullets will never hurt him.

Debbie's comments: That did not happen at their camp. It happened later, elsewhere.

Naiches and others are on horses, waiting. Goyahkla approaches them, the burning wickiup behind him. His words to them hint at the vengeance he will seek. He tells them he will visit other Apache tribes to ask them to join him in avenging their families. He carries out the visits and gathers others who will fight with them. Naiches hopes that the upcoming battle will give Goyahkla peace.

Debbie's comments: That decision to strike back was made--not by Goyahkla--but by Mangus-Colorado. Goyahkla was appointed to go to the other Apaches and ask them to join them in this battle against Mexico.

In the next panels, Goyahkla leads the others in an attack on a Mexican town. There is one small box of text: "There would be no peace" (p. 34-35) that captures what Naiches thinks their future will be. In the foreground is a young girl falling over, with a spear that has been thrust through her chest. On all fours, a few feet away, is a little boy, with a spear in his back. Naiches looks on Goyahkla and thinks his face tells of a new time for the Apaches. In Goyahkla's face there is no pity as he kills the people of the Mexican village. There are no tears, or regret, or joy. In one panel, a sign reads (p. 38-39):

CABALLERAS

APACHE

HOMBRES 5 pesos

MUJERES 3 pesos

NINOS 1 peso

Debbie's comments: That horrific scene is not accurate. I'll say more about that shortly. Regarding the sign, I think "caballeras" is meant to mean warrior. The figures on the sign aren't accurate. Roberts (Hawke's main source) says that the bounty on Apache scalps was 200 pesos for a man, and 150 for a woman or child. Because the sign is an illustration, perhaps the error is Ruth's, not Hawke's.

On Dec 14, 2016, David Bowles, author of the Garza Twins series (The Smoking Mirror is a Pure Belpre Honor Book) wrote to tell me that "caballeras" is a spelling error. It should be "cabelleras" which means scalps. His note gives me an opportunity to say a bit more about scalping. Though it is widely seen as something that Native people did, bounties were financed by governments. In her book, Angie Debo writes that, in 1835, the Mexican state of Sonora passed a law that offered 100 pesos for every scalp of an Apache warrior. In 1880, Mexican soldiers attacked an Apache camp, and took scalps of 62 men, and sixteen women and children. The city of Chihuahua welcomed them them back. Cost to the government was $50,000. The soldiers brought with them 68 women and children who were subsequently sold into slavery.

The sign is thrust into the chest of a man, lying prone, presumably killed by Goyahkla. Beside his body, Goyahkla is scalping a woman who cries out (p. 38-39):

"Por favor. Dios me libre!"

Debbie's comments: Hawke's depiction of this battle, overall, raises many questions. Barrett, Debo, and Roberts (Hawke's primary source) do not write about it the way Hawke does. They write that the attack was against Mexican soldiers (two companies of cavalry and one of infantry)--outside of a Mexican city called Arispe (or Arizpe).

There was no attack of the kind that Hawke depicts. Rather than bring "honesty" (he used that word in his Afterword) to this story, Hawke has created violent, brutal, misinformation that he is, in effect, adding to that already huge body of misinformation about Geronimo and the Apaches! At that point in Indeh, I am able to say that teachers cannot---indeed, teachers must not---use this book in a classroom to teach history of the Apache people.

As Naiches watches Goyahkla in the village, he learns what Goyahkla's new name will be: Geronimo. In the village is a banner that reads "LA FIESTA DE SAN JERONIMO." As Goyahkla moves through the village violently killing Mexicans (he beheads one), some Mexicans call out to San Jeronimo. One of the Apache's calls out to Goyahkla "Santo Geronimo" - and, Hawke tells us, that is how Goyahkla came to be known as Geronimo.

Debbie's comments: In a footnote, Barrett writes that the Mexicans at the battle called him Geronimo but does not offer an explanation. In her book, Debo writes that the Mexicans in that battle may have been trying to say his given name (Goyahkla) and that it came out sounding as if they were saying "Geronimo" or that they were calling out to St. Jerome.

My primary concern is about accuracy.

There's some small problems with inaccurate information in Part I of Hawke's graphic novel. Of utmost significance, however, is his misrepresentation of the fight that took place after his family was murdered by Mexican soldiers. Hawke's depiction is inaccurate, and it flies in the face of what I understand of Hawke's goal. It seems to me he wanted to correct the narrative of Apache's as blood thirsty savages (my words, not his), but he does the opposite. He affirms existing stereotypes and misinformation, and adds to the image of Geronimo as a savage. The information he passes along is not in his primary source, or in those that are more widely read (some are on his list of further readings). Why did Hawke do this?!

Bottom line?

I do not recommend Indeh

for use in classrooms.

for use in classrooms.

A colleague, Dr. Laura Jimenez, reviewed Indeh, too. She studies graphic novels. See her review.

Sources I used include:

Sources I used include:

- Barrett, S. M. (1906). Geronimo's Story of His Life. New York: Duffield & Co.

- Debo, Angie. (1976). Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place. University of Oklahoma Press.

- Roberts, David. (1994). Once They Moved Like the Wind: Cochise, Geronimo, and the Apache Wars. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Utley, Robert M. (2012). Geronimo. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Update, Dec 13 2016, late afternoon:

A couple of people have written to ask me about other examples of the paraphrasing. Some wonder if Hawke has plagiarized Barrett. Here's three other passages from my notes (sometimes I make tables as I read through texts):

Update: Friday, December 16, 2016

On the Amazon page for Indeh, I posted a brief review and a link to this page. There, I said this:

Greg Ruth, one of the authors of Indeh responded to my review on Amazon. Here's a screen capture of his remarks:

I think Ruth is defending the book, overall. I am focused on the attack that took place after the Mexican soldiers entered an Apache camp and killed women and children there, including Geronimo's mother, wife, and children. Here's quotes from three sources, one of which Hawke names as his primary source.

Barrett, S. M. (1906). Geronimo's Story of His Life: Taken Down and Edited by S. M. Barrett. New York: Duffield and Company.

Debo, Angie. Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place (The Civilization of the American Indian Series) (Kindle Locations 685-688). University of Oklahoma Press. Kindle Edition.

Roberts, David. ONCE THEY MOVED LIKE THE WIND: COCHISE, GERONIMO, (Kindle Locations 1674-1692). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

Below are two pages that show how Hawke and Ruth depict it. Clearly, they set the attack in a town. See the children impaled with spears?

Here's another page Hawke and Ruth did, depicting that attack:

I stand by my critique that Hawke and Ruth misrepresented what happened.

A couple of people have written to ask me about other examples of the paraphrasing. Some wonder if Hawke has plagiarized Barrett. Here's three other passages from my notes (sometimes I make tables as I read through texts):

Update: Friday, December 16, 2016

On the Amazon page for Indeh, I posted a brief review and a link to this page. There, I said this:

Hawke meant well. He had a memorable childhood experience that launched him into reading all he could about the Apaches. He tried to make a film about them but ended up doing this graphic novel, instead. Though it is not marketed to teens, teachers wonder if they can use it in their classrooms.

In short? No. In an especially violent series, Hawke and Ruth depict Geronimo and Apaches in a town, impaling women and children on spears, and beheading a man. Another woman is scalped.

None of that is true.

That particular attack was actually one in which the Apaches sought a battle with Mexican infantry who had entered an Apache camp and murdered Geronimo's mother, wife, and two children. Much of America thinks the Apaches were mindless, blood-thirsty murderers. Hawke contributes to that narrative. There are other errors, too. As such, it cannot be used to teach about the Apache people.

A full review here: [...]

Greg Ruth, one of the authors of Indeh responded to my review on Amazon. Here's a screen capture of his remarks:

I think Ruth is defending the book, overall. I am focused on the attack that took place after the Mexican soldiers entered an Apache camp and killed women and children there, including Geronimo's mother, wife, and children. Here's quotes from three sources, one of which Hawke names as his primary source.

Barrett, S. M. (1906). Geronimo's Story of His Life: Taken Down and Edited by S. M. Barrett. New York: Duffield and Company.

When we were almost at Arispe we camped, and eight men rode out from the city to parley with us. These we captured, killed, and scalped. This was to draw the troops from the city, and the next day they came. The skirmishing lasted all day without a general engagement, but just at night we captured their supply train, so we had plenty of provisions and some more guns.

That night we posted sentinels and did not move our camp, but rested quietly all night, for we expected heavy work the next day. Early the next morning the warriors were assembled to pray--not for help, but that they might have health and avoid ambush or deceptions by the enemy.

As we had anticipated, about ten o'clock in the morning the whole Mexican force came out. There were two companies of cavalry and two of infantry. I recognized the cavalry as the soldiers who had killed my people at Kaskiyeh. This I told to the chieftains, and they said that I might direct the battle.

I was no chief and never had been, but because I had been more deeply wronged than others, this honor was conferred upon me, and I resolved to prove worthy of the trust. I arranged the Indians in a hollow circle near the river, and the Mexicans drew their infantry up in two lines, with the cavalry in reserve. We were in timber, and they advanced until within about four hundred yards, when they halted and opened fire. Soon I led a charge against them, at the same time sending some braves to attack their rear. In all the battle I thought of my murdered mother, wife, and babies--of my father's grave and my vow of vengeance, and I fought with fury. Many fell by my hand, and constantly I led the advance. My braves were killed. The battle lasted about two hours.

Debo, Angie. Geronimo: The Man, His Time, His Place (The Civilization of the American Indian Series) (Kindle Locations 685-688). University of Oklahoma Press. Kindle Edition.

They went south through Sonora, following hidden ways along river courses and through mountains, to Arispe. (They seemed to know that the military force that had ravaged their camp was stationed there.) Troops from the city came out to meet them, and there was some skirmishing. The following day the whole Mexican force—two companies of cavalry and two of infantry—came out to attack. A pitched battle followed, a departure from the usual Apache ambush from a hidden position. Geronimo, because he had suffered so much from these same soldiers, was allowed to direct the fighting. (This is his story, and it may well be true.) He arranged his warriors in a crescent in the timber near the river, and the Mexican infantry advanced towards them and opened fire. Geronimo led a charge against them, at the same time extending his crescent to outflank and encircle them and attack from the rear. (At least, that seems to be his meaning.) The battle lasted about two hours, the Apaches fighting with bows and arrows and in close quarters with their spears. Many of them were killed, but when the fight ended they were in complete possession of a field strewn with Mexican dead. It was here, according to tradition, that Goyahkla received the name Geronimo.

Roberts, David. ONCE THEY MOVED LIKE THE WIND: COCHISE, GERONIMO, (Kindle Locations 1674-1692). Simon & Schuster. Kindle Edition.

Near Arizpe, one of the few important towns in northern Sonora, the party camped. Eight Mexicans rode out from town to parley: the Apaches seized and killed them on the spot. “This was to draw the troops from the city,” recalled Geronimo, “and the next day they came.” An all-day skirmish was inconclusive, but the Indians managed to capture the Mexican supply train, greatly augmenting their store of guns and ammunition.

The pitched battle— a rarity for Apaches— took place the following day: some two hundred Chiricahuas against one hundred Mexican soldiers representing two companies of cavalry and two of infantry. “I recognized the cavalry as the soldiers who had killed my people at (Janos],” insisted Geronimo. Since he had never seen the soldiers who perpetrated the massacre of his family, this claim may seem dubious. Yet keen-eyed survivors could have described the attackers to Geronimo in such detail that he could recognize their horses and uniforms when he saw them.

Because of the magnitude of his personal loss, Geronimo was allowed to direct the battle against the Mexican soldiers. He arranged the Apaches in a hollow circle among trees beside a river. The Mexicans advanced to within four hundred yards, cavalry ranged behind infantry. Armed with the vision that bullets could not kill him, Geronimo led a charge. “In all the battle I thought of my murdered mother, wife, and babies— of… my vow of vengeance, and I fought with fury. Many fell by my hand.”

The battle lasted two hours. At its climax, Geronimo stood at the Apache vanguard, in a clearing with only three other warriors. They had no rifles; they had shot all their arrows and used up their spears killing Mexicans: “We had only our hands and knives with which to fight.” Suddenly a new contingent of Mexicans arrived, guns blazing. Two of Geronimo’s comrades fell; Geronimo and the other ran toward the Apache line. In step beside him, the other Apache was cut down by a Mexican sword. Reaching the line of warriors, Geronimo seized a spear and whirled. The Mexican pursuing him fired and missed, just as Geronimo’s spear pierced his body. In an instant Geronimo seized the dead soldier’s sword and used it to hold off the Mexican who had killed his companion. The two grappled and fell to the earth; Geronimo raised his knife and struck home. Then he leapt to his feet, waving the dead soldier’s sword in defiance, looking for more Mexicans to kill. The remainder had fled.

Below are two pages that show how Hawke and Ruth depict it. Clearly, they set the attack in a town. See the children impaled with spears?

Here's another page Hawke and Ruth did, depicting that attack:

I stand by my critique that Hawke and Ruth misrepresented what happened.