Eds. note on Sunday, Sept 9, 2018: Many people responded to the thread I started on Sept. 7. Several asked if I knew about the Tribes Learning Community program. That question prompted me to add to the thread. I am adding the additional tweets as an update at the bottom of the post, along with a summary of some of the responses.

_____

"Some thoughts on the use of the word "tribe" by teachers and schools..."

September 7, 2018

Below is a thread I did on Twitter this morning. I used the spool app to compile the individual tweets so I could paste them here.

A conversation is taking place on Twitter, where some teachers are asking other teachers not to use "tribe" to describe their classrooms of students.

Some people are trying to push back on those asking that it not be done. They are pointing to dictionary definitions of the word (tribe) to say that it does not mean only Native people--that it has roots elsewhere.

That's true. The word 'tribe' is not an Indigenous word. It is used to describe many other nations/peoples around the world. But--we are talking about the US. Here, that is precisely what it evokes.

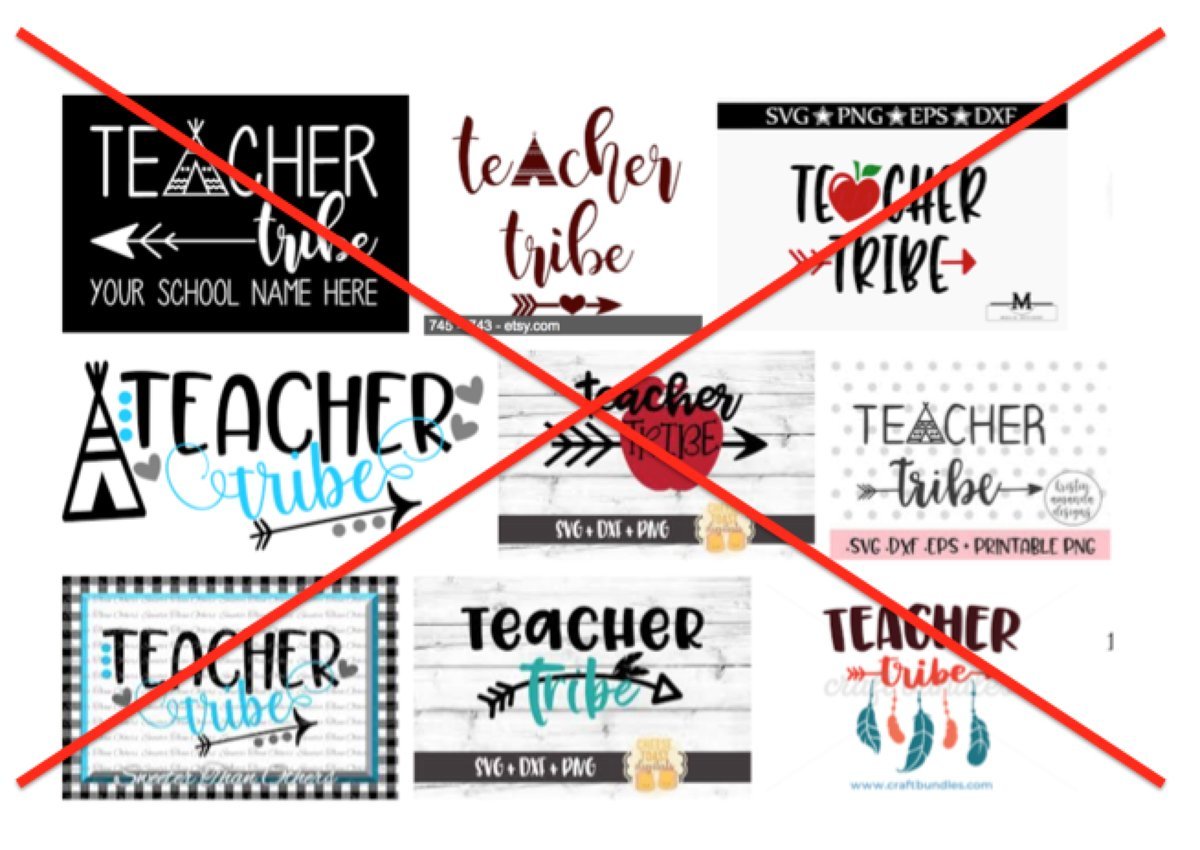

And one need only do some google image searching to see that teachers are definitely using their ideas of Indigenous people to create classroom materials for their "tribe" of kids. (I did the red x overlay to indicate NOPE.)

Here's another one (and again, I added the red x):

And here's another! I could do this all day long. If you are a teacher, please reconsider. This is a new-ish fad, but like many fads, it is harmful. Don't do it!

I took a look at the site "Teachers Pay Teachers" and found many similar problematic ideas there. "Create a tribe" is one. It is like the too-many "what is your Indian name" activities that are everywhere. They draw on stereotypes.

When you do these kinds of activities, teachers, you are introducing and/or affirming stereotypes. Remember! You're a teacher and you have a responsibility to educate children. Stereotypes do not educate! They misinform!

Librarians: when you do these kinds of activities in your libraries, you are also misinforming children.

Bottom line: there's too many ways this can--will--and DOES go wrong in a society that knows so very little about Indigenous people and our nations. I recommend you step away from using "tribe" to describe your classrooms.

Update on September 9, 2018:

Picking up on my thread yesterday about teachers using "tribe" to refer to their classrooms.... Several people have written to ask me about the pre-packaged "Tribes Learning Community" and its use of "tribes".

I gather it was created in the 1970s by Jeanne Gibbs and that its goal is to create classrooms where there was an emphasis on positive environments in the school and classroom. As the project was being developed, someone said "We feel like a family... we feel like a tribe."

Gibbs and all those involved in the development and implementation of this "Tribes Learning Community" meant well. But I wonder--given the length of time it has been in use--if any of the teachers using it had a Native child in the classroom?

If one of my daughter's teachers had been using it, I would have had a meeting with the teacher. I support efforts to foster a positive environment (I was a classroom teacher, too), but there's no need to use "tribe" to do it.

When I started this thread yesterday, I shared a few images of how "Tribes" materials look. A lot of those materials reference the Tribes Learning Community. Gibbs and her team are probably not monitoring the kinds of materials teachers use when they adopt Gibbs's program.

But Gibbs and her team -- however -- are aware that some question its use. One of their trainers is Ron Patrick. On her website, Gibbs has a letter written by him, defending the use of the word.

Correction: it isn't a letter. It is a statement 'Why the Name "Tribes"'. In it he says his tribe is Eastern Band of Cherokee. In his signature line, he used a phrase I associate with Navajo people (May you walk in Beauty). That's a bit odd, to me.

Also on Gibbs's website is a pdf "What Tribes Are and How They Work" that opens with this:

"A Native American teacher, Paula Swift Robin, is talking with four other teachers at a conference in eastern Washington."

Let's look at that sentence, critically.

Why did TLC start with that particular person? With that particular name? I think they are using that person and her identity to protect them from being questioned.

Now let's look at how they described her, as a "Native American." Is Paula Swift Robin a real person? If so, what is her nation? Does Gibbs know that Native people prefer to be identified by their specific nation?

Gibbs writes that the Tribes Learning Community is used in Native schools. There's a comment from a person in one, in Ontario, but I don't think she is Native. If you are Native and it is used in your child's school, what have you seen?

Given that the Tribes Learning Community emphasizes listening and positive classroom environments, I wonder if there's anything in any of their books about stereotyping of Native people? Do they help teachers with any of that?

I can see parts of REACHING ALL BY CREATING TRIBES LEARNING COMMUNITIES online. It has a "Matrix for Achieving Equity in Classrooms." Columns include linguistic bias, stereotyping, invisibility/exclusion. But

... there's a reference to having a "council meeting" where students can make presentations. A council meeting? Hmm...

On page 140 of the book is a:

"Step by Step Process for Group Problem Solving. 1) Ask the tribes to discuss how they feel about people spraying paint on the wall of the school."

The "tribes" discuss & then "tribe by tribe" they vote on a solution.

Are there more than one tribe in any given classroom? Or is this example one where all the 3rd grade classrooms (for example) are participating? How does the person managing all of this designate a particular "tribe"? Is it by teacher name?

If you have the book, can you share (in a reply, here) how tribes are delineated?

Summary of responses:

One parent said that her child's classroom has a "tribes agreement" and asks if it is part of the Learning Communities program. It is a key component. She also says that arrows, dreamcatchers, and teepees are everywhere. She plans to speak to the principle and is optimistic.

Many people asked about other words they could use. Others responded, suggesting team, squad, house, and family. In daughter's middle school they used "pathfinders" and "navigators" which I liked ok because they're about action and don't default to imagery that has problematic stereotyping associated with them.

Some raised questions over other problematic phrases. I've been working on a list of them, here: Common phrases.

Some are working hard to understand why it is a problem. They see or use the word to describe their (or a friend's) classroom. I appreciate that they're trying to understand. They strike me as receptive to critical thinking. Others are resistant. They assert that they (or their children) are "part Native American" and think that carries weight. A claim to being "part Native American" is used as a defense of mascots, too. These are well-meaning but ignorant and ultimately, harmful to education.