Note from Debbie: In February of 2021, I received an email from a parent who had questions about a scene in Judith Bloom Fradin and Dennis Brindell Fradin’s biography of Sacagawea. That parent is An-Lon Chen. We began an email conversation. What she wrote struck me as the sort of activity that I want readers of AICL to see. First is the questioning, and then, the research, and all though that research process, collisions with the historical record, the master narrative, and what children learn. An-Lon's essay demonstrates the work some parents do when they read a children’s book to their child. I wish more parents would write about the work they do, and share that work. Publishers do pay attention to critical examinations of the books they publish. Writers do, too (for examples, see Revised and Withdrawn).

Note on April 27, 2021: You can follow An-Lon Chen on Twitter: https://twitter.com/anlonchen

****

An-Lon Chen's Review of Who Was Sacagawea?

I didn’t set out to write a book review when I contacted Dr. Reese about a scene in chapter 4 where Sacagawea learns that her brother, Cameahwait, is going to break a promise he had made to Meriwether Lewis. I was looking for help in finding the source material for that scene in Who Was Sacagawea? by Judith Bloom Fradin and Dennis Brindell Fradin. The book was published in 2002, but is still in print today from Penguin Random House. My family loves the Who Was? biography series and this was the first time I felt the need to do any fact-checking.

An old college friend eventually helped me locate the source material in Lewis and Clark’s expedition journals. Later in this review, I will post it side-by-side with its retelling in the children’s book. It’s an eye-opening look at how much any given author’s interpretation of Sacagawea’s inner thoughts and feelings is a reflection of that author’s own beliefs and their own racial stereotypes, however well-intentioned. (Readers with time constraints can jump directly to the scene in question the Fiction? Or Deceptions? section of this review, though I feel that its full significance is best appreciated in context.)

In this review, I will shine a light on that scene, a racist illustration, and a dishonest and evasive portrayal of United States government actions in the wake of the Lewis and Clark expedition. However, the problem with Sacagawea is much bigger than one particular book. Who Was Sacagawea? is, in all likelihood, one of the better Sacagawea books out there. The authors clearly cared about their subject matter and succeeded in telling a highly engaging story about a courageous heroine. Unfortunately, the story itself has deeper problems than they seem to have realized.

I was, to be honest, caught by surprise. I am not Native American and don’t have any particular insight into, or knowledge about, Sacagawea’s story. I am, however, a Chinese-American mother of a biracial child, and I am painfully aware of how deeply racist first impressions can linger. I was disturbed enough after reading Who Was Sacagawea? aloud to my five-year old daughter that I felt morally obligated to research and write this review.

Introduction

My daughter first learned about Sacagawea from a board book that was gifted to us called A is for Awesome by Eva Chen. That board book is not the subject of this review, but I include the illustration because it visually demonstrates two important aspects of how Sacagawea's story is told.

First and foremost, all we know about Sacagawea is what white men have written about her, in the third person. We have no record of her own internal thoughts and feelings. In A is for Awesome, Sacagawea is one of the few women in the book whose page doesn’t include an upbeat, inspirational speech balloon with a quote from her (like the one shown for Ginsburg). From a few scraps in Lewis and Clark’s voluminous journals, Sacagawea’s life has been constructed, re-constructed, appropriated, and re-appropriated by white suffragists, historians, schoolteachers, writers, and politicians. We, the non-Native American audience, remain fascinated by Sacagawea because her trek across the western United States with a baby on her back makes for such a good story.

The second aspect of her life story that A is for Awesome shows us is Sacagawea’s happy smile. A smile seems like an inconsequential thing to point out, especially in light of the more obvious question - where’s her baby? But the smile is important because Sacagawea has been used by two centuries’ worth of white authors to justify white expansionism. If Sacagawea can smile about the Lewis and Clark expedition and its aftermath, then we, too, are given permission to smile.

In an email I received from Dr. Reese, she says that she doesn’t know of a decolonized children’s biography of Sacagawea. In her own words from that email:

I'd promote that (non-existent) book so much because teachers all across the country could use it to teach kids how to analyze false narratives. People who don't want the narrative disrupted won't like it, but those who do... like me, well, we'd love it.

I’m going to pause here for a confession. Much as I want this non-existent biography to exist, I too have a strong emotional response to the story as we know it. In reading through the original Lewis and Clark journals, I too am drawn by Sacagawea’s bravery and resourcefulness and resilience. I too hear the siren song that inspired her countless white biographers, who wanted to bring her back to life and give her a voice. For these reasons, I do empathize with them. Her story is not a blank slate: from the journals, we glimpse just enough of her life to desperately want to know the rest. Without any existing window into her thoughts and feelings, we invent our own motivations for her actions. We don’t necessarily set out to write a revisionist history, but we do so simply because what we wrongly perceive as a blank slate is so frustrating and so tempting.

An honest biography would refrain from reconstructing what know from the journal fragments. It would also reframe the larger story in the context of Sacagawea’s own people rather than that of the white expedition. Finally, it would tell the story of her appropriation, which is fascinating and sad in its own right.

The white suffragists who rediscovered Sacagawea had a narrative of their own to disrupt: that history is made exclusively by men. Unfortunately, these women introduced their own explicitly colonialist message. Eva Emery Dye, the novelist who popularized Sacagawea to a white audience ninety years after her death, patriotically credited Sacagawea with “unlocking the gates of the mountains, and giving up the key to her country... giving over its trade and resources to the whites, opening the way to a higher civilization.” [1] [2]

This talk of giving the country over to the whites resonates with a sizable percentage of Americans today. That is the result of misrepresentations of her life story and this country's story. I think it is important that we all take a harder look at Sacagawea’s portrayal in children’s books, and recognize that schoolchildren are receiving that same misrepresentation to this very day. I don’t believe it’s possible to address any of the errors, omissions, and fabrications in Who Was Sacagawea? without seeing how neatly they fit together in support of the colonialist, expansionist narrative first put forth by turn-of-the-century white suffragists. Again, I don’t believe the children’s book authors explicitly intended to push this particular agenda. For too many of us, it is hard to see the bias in the materials we inherit.

Revisionist History

Framing the Story

Who Was Sacagawea? opens with these words (p. 2):

In the year 2000, the United States issued a new dollar coin. Its “heads” side shows an American-Indian woman. She is carrying her baby.

Who is this young woman? Her name was Sacagawea (Sa KA ga WE a). Two hundred years ago, she went with the Lewis and Clark expedition. The explorers traveled across the American Northwest. When the explorers were hungry, she found food. When they met Indians along the way, she acted as a translator. Thanks to Sacagawea’s help, the expedition was a success.

The Lewis and Clark expedition changed American history. It helped the United States settle a huge region. This area included what became the states of Idaho, Washington, and Oregon.

This is the standard framing for Sacagawea’s adventures. Schoolchildren learn at an early age that the Lewis and Clark expedition enabled white settlement in the Northwest United States, and that the expedition would have failed at multiple junctures if not for Sacagawea. This framing sets her up as the person who scored the game-winning touchdown for the other team.

The standard framing also sets up a false timeline and false sense of historical scale. Readers are given the impression that civilization began in Idaho, Washington and Oregon only after they were organized into the states we know today. In reality, tribes on the Columbia River Plateau had been trading with tribes on the Pacific coast by canoe for thousands of years, and trading with tribes across the Rocky Mountains by horseback for hundreds of years. Although the thirty-three members of the Lewis and Clark expedition were the first white people to make face-to-face contact with these inland tribes, many of them already possessed white trade goods and knowledge of white people obtained through their intertribal trade network [3]. From their perspective at the time, the Lewis and Clark expedition was no different from any of the French, British, and Spanish expeditions that had come and gone before [4].

Below, I’m going to quote every passage in Who Was Sacagawea? that addresses the white settlement of Native lands. This is a comprehensive recitation, down to the last sentence fragment. This is the revisionist American history lesson I delivered to my daughter when I read the book aloud to her. Unteaching it is easier said than done. She trusts the written word.

Resettlement to Reservations

The only information about Indigenous peoples’ forced resettlement to reservations is ignominiously buried in a two-page encyclopedic-like sidebar about buffalo, which I will reproduce here in its entirety (pp. 20-11):

Buffalo Hunting

The American bison is also called the American buffalo. A large male bison is about the size of a small minivan. At the time of the Lewis and Clark expedition, more than 50,000,000 bison roamed the Great Plains. The Shoshone and the other Plains Indians depended on them for food, warm clothing, and shelter. Their tipis were made from buffalo hides.

Whites begin to settle on the Great Plains shortly after the expedition. The United States government tried to force the Indian tribes to live on the reservations - smaller pieces of land.

In the late 1800s, white buffalo hunters killed all but 550 American bison. Having lost their food and shelter, the Indians moved to the reservations.

During the mid-1900s, some bison were returned to the prairies. Today, 150,000 bison live on ranches and in national parks in the United States and Canada.

The passage creates the false impression that the “Indians” (it’s unclear which) voluntarily moved to the reservations. It gives no sense of the geographical size and scope of the lost homelands in comparison with the ever-shrinking, often fatally distant reservations. And it also creates a more subtle and insidious false sense of scale by enumerating the buffalo’s huge population numbers in detail while lumping together all the “Indians” into one indistinct mass. Because the terms “Indians” and “Plains Indians” are used so generically, it’s impossible to figure out which nations and tribes either term refers to.

Sacagawea’s Lemhi Shoshone, who lived in the Rocky Mountains on the other side of the Continental Divide and only hunted buffalo seasonally, are lumped in with the Plains Indians. I honestly can’t tell whether the “Indians'' who “moved to the reservations” when there were only 550 bison left, are just the Plains Indians (of which only the Mandan and the Hidatsa are even mentioned in the book), or all the Indian nations and tribes on the entire continent who were forcibly removed to reservations in the name of white settlement.

Though the Lemhi Shoshone and Nez Perce Indians of the Pacific Northwest are lauded in the book for having helped the Lewis and Clark expedition, this confusing sidebar about buffalo and Plains Indians is the closest the book comes to mentioning the wars, broken treaties, depletion of natural resources, incursion of white settlers, and political pressures that forced them onto reservations within less than a century. Let me say that again: that is the only place in the book where readers get even a hint of honest information about what Americans and the US government did to Indian people.

Exploration and Discovery

In Who Was Sacajawea? there are too many references to themes of exploration and discovery to list them all. This is the only one that acknowledges that the land originally belonged to the Indians (p. 21):

The voyagers would do more than visit the territory of the Louisiana Purchase. They would also explore what is now Idaho, Washington, and Oregon. Great Britain also had its eye on this territory. Jefferson wanted American explorers to get there first. That would strengthen U.S. claims to the region. Nobody stopped to think that the land already belonged to the Indians.

Ultimately, the exploration and discovery narrative becomes the driving force. We see the virgin landscape unfold through explorer's eyes, from the expedition’s early days in St. Louis to the beached whale at the Pacific ocean.

The discovery narrative is so powerful and compelling, it inevitably overpowers the fact presented on page 21 that the Indians were there first. Devoid of context, it is like a carcinogen warning on the side of a package. The reader sees it and forgets about it. Without having been introduced to the diverse and distinct Indigenous peoples of the “unexplored” Columbia River plateau, and without having learned anything about their relationship with the land or the miles and the millennia that it spans, it’s easy for the reader to promptly dismiss the fact that the land already belonged to the Indians.

Commemoration

At the very end of the journey, we learn (p. 95):

The Lewis and Clark expedition reached St. Louis in late September. Cheering crowds greeted the men. They were heroes. They had explored vast and distant lands. Lewis and Clark had paved the way for America's settlement of the west.

The expedition is credited with enabling the invasion and occupation of Native homelands, and the book celebrates along with the cheering crowds. In the final chapter, “Honoring Sacagawea,” we learn less about the modern-day fate of her people than we did earlier when we read that today, there are over 150,000 buffalo on ranches and in national parks (p. 102):

During the 1800s, Indians and whites fought many wars. White people did not want to honor any Native Americans. By 1900, the fighting had ended. The country was getting ready to celebrate the expedition’s 100th anniversary. That was when Americans ‘discovered’ Bird Woman. Suddenly, she became very well-known. Sacagawea has had more landmarks named for her and memorials built in her honor than any other American woman.

Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Wyoming have mountains named for Sacagawea. Washington and North Dakota have lakes named for her.

So how did the fighting end? Who won the wars? Do Indians still exist today? We never find out, as the book immediately segues into a recitation of Sacagawea’s many landmarks and memorials.

In reality, the fighting ended only about thirty years before the unveiling of Sacagawea’s first major statue at the 1905 Portland World’s Fair. White veterans of the last Northwest Indian wars against the Modoc, Nez Perce, Bannock, and Paiute tribes were present among the crowds [5]. White female suffragists unveiled Sacagawea’s statue, draped it in an American flag, and gave speeches lauding her selfless, patriotic, and vital role in America’s westward expansion [6]. Make no mistake: Sacagawea’s statue was a propaganda piece and a victory celebration.

The irony is evident in the Sacagawea dollar coin released in 2000. Whose “liberty” is the United States government celebrating, and in whose God do we trust? Certainly not Sacagawea’s, or that of her Lemhi Shoshone tribe, or that of any other contemporaneous American Indian nation.

Erasure

At the 1905 Portland World’s Fair, National Woman Suffrage Association President Anna Shaw hailed Sacagawea as a memory of a conveniently vanishing race [7]:

“Your tribe is fast disappearing from the land of your fathers. May we, the daughters of an alien race who slew your people and usurped your country, learn the lessons of calm endurance, of patient persistence and unfaltering courage exemplified in your life…”

Who Was Sacagawea? propagates the same nostalgic myth of the vanishing Indian by concluding with a recitation of Sacagawea’s many monuments and memorials while failing to mention that all the Indigenous tribes encountered by the reader in the book still exist today. For this review, I did a lot of research and learned a lot.

Sacagawea’s Lemhi Shoshone lived in their relatively isolated homeland valley for two more years after the 1905 Portland World’s Fair. Though they had remained mostly neutral during the Nez Perce, Bannock, and Sheepeater Wars, they were ultimately driven by political and economic pressures to relocate to the Fort Hall Reservation, 200 miles away. Tribal members refer to this exile from their homeland as their own “Trail of Tears” [8]. Though the small number of Lemhi Shoshone who remained in or returned to their homeland have not succeeded at obtaining federal recognition, they remain a distinct society today [9]. The Lemhi Shoshone who relocated to the Fort Hall Reservation are now part of the Shoshone-Bannock Tribes, a federally recognized sovereign nation with over 5,900 members.

The Nez Perce tribe that aided the expedition after they crossed the Bitterroot Mountains is a federally recognized tribal nation with over 3,500 citizens. Though the Nez Perce Reservation is located on part of their homeland in north-central Idaho, the Nez Perce who aligned with Chief Joseph during the Nez Perce War of 1877 spent eight long and deadly years in exile on reservations in Kansas and Oklahoma before finally being allowed to return to the Pacific Northwest in 1885.

The Mandan Indians in North Dakota who helped feed the expedition during the winter of 1804-1805 were ravaged by multiple smallpox epidemics and allied with the Hidatsa and the Arikara in order to survive. Today, they are the Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, with 16,770 enrolled members. In 1949, the federal government displaced over 80% of their population in order to build the Garrison Dam. The loss of the river-valley homeland that had been their agricultural livelihood left The Three Tribes devastated economically, socially, and spiritually [10]. In 1985, Congress awarded them $149.5 million in just compensation for the lands underneath the lake created by the dam. This lake is called Lake Sakakawea, so named by the US Army Corps of Engineers who built the dam [11].

There are currently 574 federally recognized tribes and 1.9 million tribally enrolled members in the United States today. This tally doesn’t include the Chinook and Clatsop tribes of the Lower Columbia River that are featured in the book for having traded with the expedition at the very end of their journey. The Chinook Nation, which includes both these tribes, is still fighting for federal recognition. Their struggle is not the focus of this piece, but it’s well worth visiting their own website to learn more. Ironically, because they never signed a ratified treaty or officially ceded homelands, they are now denied COVID relief and other forms of federal aid [12].

All these nations and tribes survived the white occupation of their ancestral homelands. So why were they written out of Who Was Sacagawea? Why do we get a modern-day update on the buffalo and the dollar coin and the namesake lake in North Dakota, but no update on the people themselves? Because in order to justify the discovery and settlement narrative, we need to pretend that the people we displaced no longer exist.

I’m going to shift gears at this point, from the larger historical canvas to the scene in the book that took me down the path that led to this review.

Fiction? Or Deceptions?

We know just enough from Lewis and Clark’s journals to be deeply drawn to Sacagawea as a human being, and we become emotionally invested in giving her a happy ending. I think many children’s biographers paint a false portrait of Sacagawea not for ideological reasons, but because letting her share in the happy ending of the white expedition is the only way to give her a happy ending at all. Rather than using Sacagawea’s story to reflect on hard truths about white settlement of Indigenous homelands, we now use it to assuage our collective guilt.

Most narratives downplay how little agency Sacagawea had in her own life. Sacagawea's husband, Toussaint Charbonneau, was a predatory man who “married" at least five Native American girls, the last when he was 80 and she was 14 years old [13]. According to the Lewis and Clark journals, Sacagawea herself was captured in a raid at age 10 or 11 by the rival Hidatsa tribe (referred to in the book as the Minnetaree) and either sold, traded, or gambled away to Charbonneau when she was 13.

The authors of Who Was Sacagawea? go to great lengths to try and make Sacagawea’s backstory palatable to younger readers. In the first few pages, they insert an awkward paragraph explaining that like all Shoshone girls, she would have been married at age 13 or 14 to an older man within her own Shoshone tribe. My impression is that this is intended to soften the blow of her ensuing capture and forced marriage to Charbonneau.

In Chapter 4, Sacagawea emotionally reunites with her Lemhi Shoshone tribe in present-day Idaho after five years and 600 miles of separation. She learns that her brother Cameahwait is the new chief. He becomes part of the translation chain that allows the Lewis and Clark expedition to trade for horses and guides from the Shoshone in order to cross the Bitterroot Range of the Rocky Mountains.

Here, the book’s authors launch into speculation as to why Sacagawea stayed with the white expedition instead of staying with her people, conveniently avoiding the possibility that she may not have had a choice. But even that editorialization isn't enough, because the book also introduces a new, illustrated plot point (pp. 60-61):

Bird Woman must have been tempted to stay with her people. However, she chose to move on with the Corps of Discovery. We can only guess why. Perhaps she felt loyal to the explorers. They had treated her and Pomp kindly. She may never have felt so important before. The chance to visit other Indian tribes and see the ocean must also have been exciting to a young girl.

The explorers were still among the Shoshone when Bird Woman overheard something shocking. Her brother had changed his mind. He was going to break his promise. He was going to keep the horses and take his hungry people to hunt buffalo. Sacagawea told Charbonneau what she had learned. She asked him to tell Captain Lewis. Lewis confronted Cameahwait. The chief was ashamed. He would keep his word after all, he said. Once again, Sacagawea had helped save the expedition.

This is the point where I went on a protracted hunt for the original source material. The passage above felt a little too convenient. Here is a photo of that page:

This scene establishes Sacagawea’s brother as a deceitful, unreliable Indian, plants Sacagawea firmly on her husband's side, and firmly aligns her with the white expedition. The reader can relax and enjoy the rest of the book, believing that Sacagawea chose of her own free will to stay with the good guys.

Is it any wonder that some Native Americans think of Sacagawea as a traitor? Look at the illustration in the book above: Sacagawea is eavesdropping from behind a tree, and she’s about to snitch on her Shoshone brother to her white husband. As I am about to demonstrate, this scene is entirely fictitious. No part of it ever happened. But it appears in this biography. We’re conditioned to believe the words in print without question.

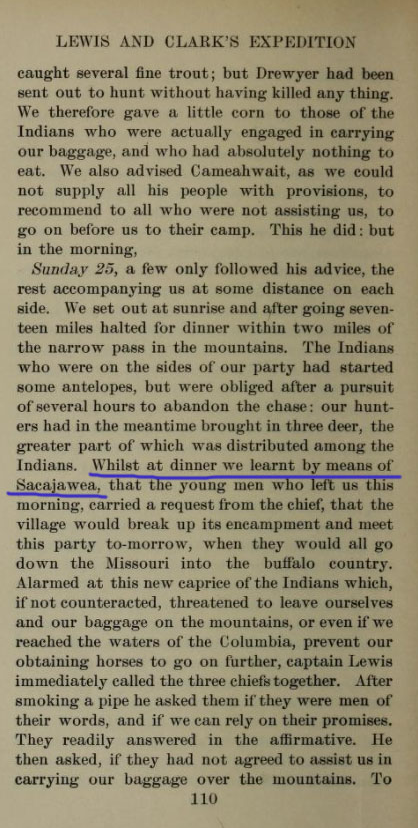

Here is the actual source material, with the only mention of Sacagawea underlined in blue. I will guide you through it, shortly. [14]

“Whilst at dinner we learnt by means of Sacajawea” (page 110) is the only mention of Sacagawea in this entire passage. All we learn from it is that she conveyed some information. There is no indication about how or why she chose to share that information, or that it was secret in any way, or that she had overheard it from behind a tree. All those details provided on page 60 and 61 of Who Was Sacagawea?, in other words, were invented wholesale.

The actual information being conveyed is more difficult to decipher without some context. I will summarize and give the needed background.

At the time of the journal passage, the expedition and Cameahwait’s party are camped some distance away from the Shoshone village in the Bitterroot Mountains. At this point, Lewis and Clark have traded for some horses from Cameahwait, and Cameahwait has indicated willingness to trade more. Lewis and Clark want the entire combined party to travel to the Shoshone village in order to continue bargaining for their needed horses. Cameahwait, however, has just instructed a runner (as conveyed by Sacagawea) to have his people leave the village and meet Lewis and Clark’s party at their current encampment instead.

From there, they will make their seasonal journey down to the buffalo-hunting grounds on the Great Plains of present-day Montana. All of Lewis’s subsequent pontification refers to the horses he thinks he’s entitled to once they reach the Shoshone village in the mountains, not to any horses that have actually been promised. At the end of page 111 in the journals, Cameahwait agrees to change his plans. In subsequent journal entries, everyone arrives at the village and Lewis bargains for his horses.

Nowhere is there any indication that Cameahwait attempted to steal back horses that he had already traded away, or that Sacagawea saved the expedition by overhearing secret plans and ratting on her brother to her husband. The passage in Who Was Sacagawea? is entirely fictitious.

Not only is it fictitious, it is actively harmful. Why was that passage so believable that two decades’ worth of editors, reviewers, librarians, parents and schoolchildren never (to my knowledge) questioned it? Because it plays into our negative stereotypes of Native Americans. Because the shifty, capricious Indian chief fits neatly into our worldview and our preconceptions.

As for Sacagawea’s motivations in leaving behind her Shoshone people and staying with her husband, I found no information in the Lewis and Clark journals other than the following passage about the Shoshone man she had been betrothed to. As it turns out, he was still alive but didn’t want her back (p. 118).

When we brought her back, her betrothed was still living. Although he was double the age of Sacajawea, and had two other wives, he claimed her, but on finding that she had a child by her new husband, Chaboneau, he relinquished his pretensions and said he did not want her.

I assume that the authors of Who Was Sacagawea? read the same passages I read. Why was the passage above not offered as a possible reason Sacagawea stayed with the white expedition? Why was the passage about Cameahwait re-imagined into a traitorous plot point?

Because we want that happy ending so badly. Portraying Sacagawea as winning with the good guys is much easier than addressing what happened to those other guys. Sacagawea gets the happy ending we want her to have, but it is at the cost of being airlifted to the other team.

Sacagawea’s Son

I have one last critique of Who Was Sacagawea? in particular, and the Sacagawea story in general. Both have to do with Sacagawea’s baby.

The illustrator of Who Was Sacagawea?, like the authors, clearly cares about his characters and has clearly done research in bringing them to life. That said, I can’t get over this picture of Sacagawea’s one-year old son:

The hunched back, the weak chin, and the enormous feet look like they were inspired by popular imagery of Neanderthals. The Lewis and Clark expedition was 200 years ago, not 40,000 years ago. I’m sure the illustrator meant well. But it’s easy for subconscious bias like this to creep into illustrations, and go uncaught by an editorial and publishing team. As with the fictitious plot point about the traitorous Indian chief, this baby is believable only because of our own latent stereotypes and preconceptions.

The final story element that appears in every account of Sacagawea’s life is William Clark’s fondness for both her and her child. After repeated offers, Clark adopted the boy when he was about six years old. Sacagawea died shortly after giving birth to his sister two years later. Clark adopted the baby girl as well. She doesn’t appear in his records at all after her initial adoption, and may not have survived past childhood.

It’s easy for contemporary readers to see Clark’s adoption of Sacagawea’s son as being sweet and heartwarming, without recognizing the underlying worldview and preconceptions of the era: kind white adoptive parents will civilize the savage child and give that child a better life. I have yet to see any account of Sacagawea’s life that addresses the adoption of her children in the context of the United States government’s soon-to-be-realized practices of forced assimilation, now commonly referred to as cultural genocide.

The broader topic of assimilation is far too complex for a review like this to address. I’ll instead follow Dr. Reese’s advice and point readers to the recent film Dawnland, which tells the heartbreaking story of how Indigenous children were removed from their homes in order to “save them from being Indian.” The investigation shown in Dawnland was conducted through Maine’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission, the first of its kind in the United States. Last year, then-Congresswoman Deb Haaland (now Secretary of the Interior), a member of the Laguna Pueblo Tribe, introduced a similar bill at the federal level. The main section of this bill is well worth reading.

Decolonizing Sacagawea

Above, I wrote briefly that an honest biography of Sacagawea, with the tragic parts told, would look very different from the biographies that schoolchildren read today. When we zoom in, the exploration and discovery story is endlessly appealing. But when we zoom out, we can better see the false framing, the false timeline, the invasion and occupation story, the assimilation story, the appropriation, the wishful thinking, the latent stereotypes, and the ongoing harm.

I honestly don’t believe that any of this can be fixed for the target audience of the Who Was? series. A newly rewritten Who Was Sacagawea? with corrections made to all its falsehoods and errors would still be a dramatization beyond what we can reasonably know about Sacagawea’s own internal motivations, and it would still feature the same exploration, discovery, and settlement narrative. Tamper too much with any of these elements, and the story loses its appeal. Despite everyone’s best intentions, it would slowly get zoomed back in and edited back down to its previous form, perhaps with a few awkward and unconvincing disclaimers.

Older students could perhaps benefit from an entirely different treatment of Sacagawea’s story, one that bypasses the false dramatization and instead presents all the primary source journal fragments in their original form, along with the tools and context necessary to understand why and how they got assembled together to fit the familiar, colonialist narrative. Even then, there are many chasms where such a book and its readers could easily get trapped. This would prevent them from reassembling the puzzle pieces into a more honest form. I don’t pretend to be able to navigate past these chasms, but I will point them out because I’ve encountered each of them multiple times over the course of researching this piece.

First and foremost, there’s the strong desire to save both Sacagawea and the Lewis and Clark expedition from being cast as the bad guys. This is understandable, given that the explorers weren’t the ones who authorized the invasion, occupation, and cultural genocide that followed the expedition. It can be difficult to grasp that even though the Lewis and Clark expedition didn’t directly do the harm, it was and is an extremely effective vehicle for justifying the harm done to Native peoples. This justification happens in other places and times, too, as shown by the engineered lake over Mandan Indian homelands--a lake that was named for her, and the statues of her, everywhere. Her name is used to serve the same purpose: justifying colonialism.

A decolonized biography of Sacagawea would need to focus on dismantling the propaganda rather than arguing about everyone’s good intentions. Straw man arguments against Sacagawea being a traitor tend to fall into this trap. No, she herself wasn’t a traitor in the Benedict Arnold sense. She didn’t name the lake. But her story routinely gets told to children in a way that betrays her people: revisionist history followed by erasure and hollow commemoration. We lose sight of the betrayal when we take swings at the straw man.

Another potential chasm is the fact that Sacagawea and her descendants proudly figure in multiple tribes’ oral histories, at odds with the scanty written record that says she died at age 25. It’s tricky to avoid passing judgment on the veracity of competing claims, and it’s even trickier to avoid taking tribal members’ pride in their kinship with Sacagawea as license to continue telling our own harmful version of the story. My hope is that we can respect the Lemhi Shoshone, Shoshone-Bannock, Wind River Shoshone, Hidatsa, and Comanche histories while recognizing that popularizing one or more of them would have little effect on the revisionist history currently being taught to children. Even though we could, in theory, give Sacagawea a happier personal ending by adopting a version of the story where she leaves her white husband and reunites with her own (Shoshone or Hidatsa or Comanche) people, the happier personal ending doesn’t change the broader political and historical canvas.

Perhaps the most significant chasm is the whiteness of the source material itself. The Lewis and Clark expedition diarists, despite their best efforts, were not reliable ethnographers. Their journals contain numerous misrepresentations of Indian traditions and customs. An honest biography would need to address and compensate for those misrepresentations, which is much easier said than done. Sacagawea spent most of the journey alone among white people. She’s an easy heroine to offer up to white kids precisely because of her isolation. They get a semblance of diversity without ever needing to experience an Indigenous society or lifeway or worldview.

I haven’t commented on the authenticity of any of the cultural details in Who Was Sacagawea? because I am not Native American myself, but even I cringed every time the book made blithe generalizations about “Indian” customs without specifying which tribe they belonged to. Is it common for all Indians to have many different names during childhood (p. 6)? Do all Indians refer to late October as “Moon of the Falling Leaves” (p. 23)? Do all Indians refer to the middle of winter as “Frost in the Tipi” (p. 31)? No, of course not. These cultural details, even if they’re authentic, are unique to specific tribes. But mixing and matching those details is apparently good enough for white authors writing for white children. Sacagawea’s story unfortunately lends itself to this surface-level treatment because the reader meets a lot of tribes without lingering long enough to differentiate between them.

Getting past these chasms goes well beyond my own knowledge or ability. I will, however, offer one screening question for any future biography of Sacagawea that purports to be decolonized: is the reader upset by the end of the story? Has the reader acquired enough cultural and historical context from outside the expedition itself to mourn the government betrayals and the lost homelands? If the reader is not actively mourning, then perhaps the book in their hands is still the same old story that continues to deny the truths of what happened.

If this sounds depressing, there are other ways to offer hope. There are other Indigenous heroes and heroines to celebrate, especially for the younger audience of the Who Was? series. There are contemporary heroes and heroines who would help kids realize that Native Americans still exist today. Endlessly rehashing the Sacagawea story seems to make white people feel better, but it’s ultimately an avoidance mechanism. It’s an easy way to get a Native American heroine onto a bookshelf without challenging white mindsets and white worldviews. It pushes better books off the shelf and prevents better books from being written.

There are better books already out there. My daughter and I are slowly making our way through some of the selections on Dr. Reese’s website. We both loved Buffalo Bird Girl: A Hidatsa Story by S. D. Nelson (Abrams, 2013). That’s a start. I too have a lot to learn.

References

[1] Blee, Lisa (2005). Completing Lewis and Clark's Westward March. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 106(2), 245. Retrieved from https://www.ohs.org/research-and-library/oregon-historical-quarterly/upload/Blee-Completing-Lewis-and-Clark.pdf

[2] Oregonian, July 7, 1905. Retrieved from https://oregonnews.uoregon.edu/lccn/sn83025138/1905-07-07/ed-1/seq-11/

[3] Conner, Roberta (2006). Our People Have Always Been Here. In Josephy, Alvin Jr. (ed.), Lewis and Clark through Indian Eyes: Nine Indian Writers on the Legacy of the Expedition (p. 90). Vintage.

[4] Ibid, p. 100.

[5] Blee, Lisa (2005). Completing Lewis and Clark's Westward March. Oregon Historical Quarterly, 106(2), 239. Retrieved from https://www.ohs.org/research-and-library/oregon-historical-quarterly/upload/Blee-Completing-Lewis-and-Clark.pdf

[6] Ibid, pp. 239-245.

[7] Brooks, Joanna (2004). Sacajawea, Meet Cogewea. In Fresonke, Kris, and Mark Spence (eds.), Lewis & Clark: Legacies, Memories, and New Perspectives (p. 184). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt4q2nc6k3/

[8] Campbell, G. (2001). The Lemhi Shoshoni: Ethnogenesis, Sociological Transformations, and the Construction of a Tribal Nation. American Indian Quarterly, 25(4), 556-567. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/1186016

[9] Ibid, p. 567.

[10] “MHA Nation History.” Mandan, Hidatsa, and Arikara Nation, MHA Nation. Retrieved April 6, 2021 from www.mhanation.com/history

[11] Cross, Raymond (2004). “Twice-born” From the Waters. In Fresonke, Kris, and Mark Spence (eds.), Lewis & Clark: Legacies, Memories, and New Perspectives (p. 117). Berkeley: University of California Press. Retrieved from http://ark.cdlib.org/ark:/13030/kt4q2nc6k3/

[12] Fernando, Christine (2021, February 27). “Pandemic leaves Chinook Nation in Washington, other tribes not federally recognized, at higher risk.” The Seattle Times. https://www.seattletimes.com/seattle-news/health/covid-19-pandemic-leaves-chinook-nation-other-tribes-without-us-recognition-at-higher-risk/

[13] TW - sexual violence. “Toussaint Charbonneau.” National Parks Service. U.S. Department of the Interior, April 10, 2015. https://www.nps.gov/jeff/learn/historyculture/toussaint-charbonneau.htm

[14] Lewis, Meriwether & Clark, William (1814). “History of the expedition in command of Captains Lewis and Clark to the sources of the Missouri : across the Rocky Mountains down the Columbia River to the Pacific in 1804-6 : a reprint of the edition of 1814 to which all the members of the expedition contributed” (pp. 110-111). Toronto: Morang.

Retrieved from https://archive.org/details/historyofexpedi02lewi/page/110/mode/2up