Editor's Note, May 14, 2014 8:00 PM: Limbaugh won the Children's Book Council's 2014 Author of the Year Award.

Editor's Note, June 17, 2014, 5:08 AM: Yesterday, Rush Limbaugh made Teaching for Change and its Executive Director, Deborah Menkart, the targets of his venom. In his segment he derides her for not stocking his books. He says he has characters of color in his books that are "heroes." My review (below) illustrates that he created a Native character to fit his agenda. She is not a hero. His use of the word "diversity" is spurious. See Rush Limbaugh Calls Teaching for Change Racist for Promoting Diverse Children's Books

~~~~~

Rush Limbaugh's Rush Revere and the Brave Pilgrims

Review by Debbie Reese, March 23, 2014

Rush Limbaugh's book,

Rush Revere and the Brave Pilgrims is a best seller. That status means he is on the Children's Book Council's (CBC) list of contenders for Author of the Year. People in children's literature were shocked when they saw his name on the list. Some suggested that the best selling status was not legitimate. The CBC responded with

an open letter explaining why Limbaugh is on the list:

The Author of the Year and Illustrator of the Year finalists are determined solely based on titles’ performances on the bestseller lists – all titles in those categories are listed as a result of this protocol. Some of you have voiced concerns over the selection of finalists from bestseller lists, which you feel are potentially-manipulable indications of the success of a title. We can take this into consideration going forward, but cannot change our procedure for selecting finalists after the fact.

The CBC letter goes on to say that children will choose the Author of the Year. Voting starts on March 25th. The CBC says that they have procedures in place to eliminate duplicate, fake, and adult votes.

Transcripts on Limbaugh's website state that his company, Two If By Tea, bought many copies of the book and sent them to schools. In this

transcript of Limbaugh's conversation with a 10 year old girl from Cynthiana, Kentucky, she thanks him and Two If By Tea for sending books to her school. He asks how many books they got, and she replies "I think we got 60." He goes on to say "We sent like 10,000 or 15,000 books to schools as a charitable donation across the country." At the end of the transcript, he says they donated over 15,000 copies. Presumably, the other authors on the contender list for author of the year do not buy thousands of copies of their own books and donate them to schools.

Sales aside, what does the book actually say (I read an electronic copy of the book and cannot provide page numbers for the excerpts below)?

Limbaugh opens the book with "A Note from the Author" wherein he says that America is exceptional because "it is a land built on true freedom and individual liberty..." and that:

The sad reality is that since the beginning of time, most citizens of the world have not been free. For hundreds and thousands of years, many people in other civilizations and countries were servants to their kings, leaders, and government. It didn't matter how hard these people worked to improve their lives, because their lives were not their own. They often feared for their lives and could not get out from under a ruling class no matter how hard they tried. Many of these people lived and continue to live in extreme poverty, with no clean water, limited food, and none of the luxuries that we often take for granted. Many citizens in the world were punished, sometimes severely, for having their own ideas, beliefs, and hopes for a better future.

The United States of America is unique because it is the exception to all this. Our country is the first country ever to be founded on the principle that all human beings are created as free people. The Founders of this phenomenal country believed all people were born to be free as individuals.

Nowhere in that note does he reference slavery of American Indians or African Americans in the United States, pre- or post-1777. The word "slave" does appear in his book, though, when his protagonist, "Rush Revere" and two students who time travel with him to 1621 meet Squanto. The two students are a white boy named Tommy and a Native American girl named Freedom.

When Limbaugh's Squanto speaks, he does so with perfect English. Why? Because, Squanto explains, he had been kidnapped and taken to Spain. He says that Bradford's God rescued him from slavery in Spain when Catholic friars helped him escape.

See that? Limbaugh tells us that Spain is one of those places where people could not be free. Slaves in the United States of America? Nope. Not according to Limbaugh. The way that he presents Squanto's enslavement fits with his exceptionalism narrative. How, I wonder, are parents and teachers dealing with that narrative? At Betsy Bird's blog with School Library Journal,

Jill Dotter says (in a comment) she is a Libertarian, and that she bought Limbaugh's book for her son. He loves it. She doesn't note any problems with the book. I'll post a question and see what she says.

Squanto continues, saying that he shows his gratitude to Bradford's God by serving his "new friend and holy man, William Bradford." Limbaugh would have us believe that Squanto was loyal to Bradford. The facts are otherwise. Squanto was an opportunist who played one side against the other for his own benefit (see Debo,

A History of the Indians of the United States; Jennings,

The Founders of America, and Salisbury,

Manitou and Providence: Indians and Europeans, 1500-1643.)

In the Prologue, Limbaugh introduces his readers to his buddy, "Rush Revere" who is a history teacher from the twenty-first century at a school where they hire only the "smartest and most educated" teachers. In Limbaugh's world, apparently, it is smart to completely ignore slavery as part of US history.

|

| "Freedom" |

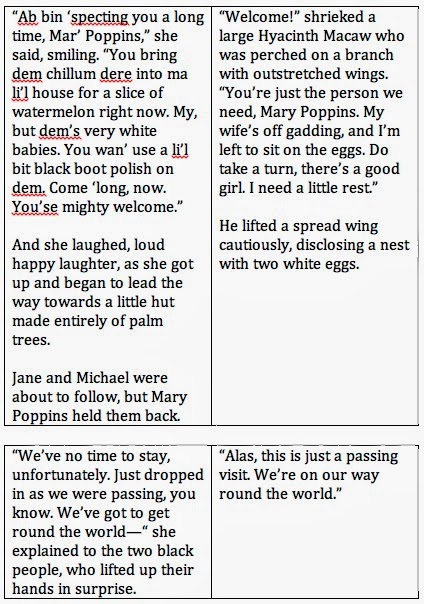

Of interest to me is the character, Freedom, in Limbaugh's book. Mr. Revere loves her name. She has long black hair. One day she wears a blue feather, the next day she wears a yellow one. Other students don't like her, but Mr. Revere is intrigued by her. She has dark eyes and a determined stare. She speaks "from somewhere deep within." From her grandfather, she learned how to track animals. She and Mr. Revere's horse, Liberty, can read each other's minds. Liberty can also talk, which I gather from reviews, is what children like about the book. Freedom explains that he must be a spirit animal, that "there is an Indian legend about animals that can talk to humans." She wondered if Mr. Revere was "a great shaman" when she saw Revere and Liberty enter the time travel portal. (Note: Screen capture of Freedom added at 5:30 PM on 3/23/2014. Mr. Revere gazes at her hair, thinking "It was silky smooth, as if she brushed it a thousand times.")

What is behind Limbaugh's creation of a Native American girl named Freedom?

Later in the story, we learn that her mother (we never learn of a specific tribe for Freedom or her mother) named her Freedom because she was born on the fourth of July. Let's think about that for a minute. There are obvious factual errors in the book related to Limbaugh's presentation of slavery. With his character, Freedom, we see how fiction can be manipulated in the service of a particular ideology. Limbaugh is creating a modern day Native girl as someone who holds the same views as he does. Packed into, and around, his Native character are many stereotypes of Native peoples. Does he cast her in that way so that it isn't only White people who view history as he does?

I think so. He casts Squanto and Samoset that way, too.

As noted earlier, Squanto is in Limbaugh's book. So is "Somoset" (usually spelled Samoset). Both speak English. In the note at the end of the book, Limbaugh lists William Bradford, Myles Standish, William Brewster, Squanto, and Samoset (spelled right this time) as brave, courageous, ordinary people who accomplished extraordinary things. Remember how Limbaugh presented Squanto as "serving" Bradford?

Massasoit, who is also part of Limbaugh's story, is not amongst Limbaugh's list of brave and courageous people. Maybe because he spoke "gibberish" instead of English. There's more I could say about Limbaugh's depiction of Massasoit, but I'll set that aside for now. The point is, Limbaugh's book is a factual misrepresentation of history that Limbaugh is donating to schools. How are teachers using it? I think we ought to know.

I will not be surprised if Limbaugh wins the contest when kids vote. They seem to like the horse. Some people seem to think it doesn't matter what kids read, as long as they read. Others, of course, agree with Limbaugh's political views and, no doubt, pass those views on to their children.

As CBC's open letter indicates, they will be revising their criteria. With Limbaugh on the short list for Author of the Year, their credibility is suddenly in question. I had concerns with CBC prior to this when I saw books that stereotype American Indians on CBC Diversity's bookshelf at Goodreads. Amongst those books is Scott O'Dell's

Island of the Blue Dolphins, which is one of the best selling children's books of all time. It is fraught with problems in the ways that O'Dell presents his Native character. I asked that it be removed, but that could not be done. As some have said, what I call a stereotype, someone else views as a role model.

Perhaps Limbaugh's book will push CBC to think more critically about the distinctions between quality, viewpoint, and quantity--especially as census data points to the rapid change in majority/minority statistics and the country tries to recognize all of its citizens.

Below are the notes I took as I read Limbaugh's book. I invite your thoughts on the book, what I said about it, what I left unsaid... Please use the comment option below to submit your thoughts. And--another 'thank you' to K8 for giving me permission in January to post

her excerpts/comments about Limbaugh's book.

~~~~~

Detailed notes I took as I read Rush Revere and the Brave Pilgrims; some are not part of the review but could use further study and analysis:

When chapter 1 opens, the principal is telling a classroom of honors history students that their teacher has to take leave. But, he reminds them, their school has the smartest and most educated teachers, and, well, Mr. Revere (remember, in this book, "Mr. Revere" is Rush Limbaugh), the substitute is among the smartest and most educated.

He starts some banter with the students, and notices a girl in the very last row, in the corner:

Her dark hair had a blue feather clipped in it. She wore jeans with a hole in one knee, but I could tell it wasn't a fashion statement. I looked at the seating chart and noticed the girl's name, Freedom. What an unusual name. Personally, I couldn't help but be a fan!

He brings his horse into the classroom. The students gather round, but Freedom hangs back, "unsure of whether she was welcome to join them in their new discovery." Another student, Elizabeth, tells her not to get too close, because the "horse might smell you and run away." Freedom goes back to her desk. Mr. Revere sets up a way for students to watch him and Liberty time travel, and takes off, heading to the portal. Just as he does that, he sees that he was being watched, by Freedom.

Mr. Revere talks with William Bradford and his wife, before they set off from the Netherlands. Revere returns to the present and asks the students what they think of Bradford choosing not to take his little boy on a "death-defying voyage across a tempestuous sea." Freedom, with "dark eyes" and a "determined stare" just like Bradford's, raises her hand and speaks "from somewhere deep within" saying

"I could tell they loved their son, more than anything. They only wanted what was best for him. It took courage for the Pilgrims to leave their homes and travel into the unknown. But it takes more courage to travel into the unknown and leave someone you love behind."

Chapter 3

Freedom and Tommy stay after class (Tommy got in trouble with the principal). Revere thinks Freedom stayed behind because she knows he's doing the time traveling. Liberty (the horse) seems to have disappeared, but Freedom says:

"Liberty, he's still in the room," she calmly said. "I can smell him."

Revere thinks Freedom has a gift. Revere decides to tell Freedom and Tommy that Liberty can make himself invisible, but Freedom says he doesn't disappear, that he just blends into his surroundings. Revere wonders why Freedom could see him, and she says

"I've had lots of practice tracking animals with my grandfather."

Because Liberty can talk, Freedom says:

"he is more than a horse. He must be a spirit animal. There is an Indian legend about animals that can talk to humans."

Revere asks Freedom if she saw he and Liberty jump through the time machine portal earlier that day, and she says:

"Yes, I did. At first I wasn't sure what I saw. As I said, I though Liberty must have been a spirit animal. Maybe you were a great shaman. i did not know. But I'm glad to know the truth."

She leaves, and Tommy and Rush ride Liberty back in time to the Mayflower where they meet Myles Standish. When it is time to leave, Liberty is sleeping. They wake him with an apple and he asks if he missed anything important:

"Nothing too important," I said, still feeding him apples. "But it's time to jump forward to the end of the Mayflower voyage. There's a new land to discover! There are Indians to befriend and a new colony to build. And a celebration to be had called Thanksgiving!

When the ship captain tells them they're going to land at Cape Cod, Tommy wonders if Indians will be in the woods. Myles Standish says:

"Yes, probably Indians," Myles said. "We will do what we must to protect ourselves. We have swords and muskets and cannons if need be."

Chapter 6

Tommy and Revere and Liberty return to the classroom where Tommy tells the principal all he's learning from Revere. The next day, Tommy and Freedom are waiting for Revere at school:

She was wearing a faded yellow T-shirt and faded jeans. It was hard not look at her black hair. It was silky smooth, as if she brushed it a thousand times. This morning there was a yellow feather clpped in it.

She wants to time travel with them. Revere has winter clothes for her and Tommy because the trip will be to wintertime. Freedom says "I'm a wimp when it comes to the snow." Earlier in the book, Freedom and Liberty started talking to each other without speaking. They can hear each other's thoughts. Tommy asks about it. Revere says:

It's apparent that Freedom has a gift. How long have you been able to communicate with animals?"

"Since I was eight, I think," said Freedom. "My grandfather says that animals can feel what we feel, especially fear. Our emotions are powerful. He trained me to use emotions to speak to the mind of an animal."

Before they leave, Revere tells them it will be cold, and that the Pilgrims were "even attacked by Indians." Freedom replies by talking about the cold, and Tommy says:

"Wait," Tommy said wide-eyed. "Did you say they were attacked by Indians? I thought the Indians were their friends. How many Pilgrims died?"

Rush tells him that none died, and that "friendly Indians" came later. Liberty says he hopes they had friendly horses, too. Elizabeth (another student who happens to be the principal's daughter) shows up. Her and Freedom get into a fight when Elizabeth takes a photo of Freedom dressed as a Pilgrim and says she's going to share it. Elizabeth storms off.

Revere asks Freedom if she can ride a horse. She sprints up to, and jumps up onto Liberty's back. They travel to 1620, Plymouth Plantation. Revere approaches Bradford and Standish, telling them that he and Tommy had been out exploring and

"were fortunate to come across a young Native American girl riding a horse. Strange, I know. But the girl took a liking to us and helped us find our way back to you!"

Bradford tells Revere that Myles and his men had survived an Indian attack, that Mrs. Standish had died, and many others are sick. He also says they found a place to build their town

"When we arrived we found barren cornfields with the land strangely cleared for our homes."

Revere asks if someone once lived there, and Bradford says "Perhaps" but that it has been deserted for years. They talk of building a fort. Revere says he remembers building forts in his living room, using blankets and chairs, and using Nerf guns to keep out his annoying little sisters. Smiling, Standish says those guns probably wouldn't be effective for "savage Indians."

Revere heads off up a hill. Tommy and Freedom approach, on Liberty. Tommy says "We saw Indians!" and Rush asks 'what' and 'where' and 'how many.'

Freedom says there were two scouts, watching, and that they wore heavy pelts and furs and were only curious. They time travel to 1621.

Chapter 7

They arrive in 1621 and see a deer nearby. Tommy asks Freedom if she can talk to it. She stares intently at it, and it approaches then. She walked over to it. All around them are tree stumps. The Pilgrims had cut down trees to make their homes. In the Pilgrim town they meet up with Bradford. Revere introduces Freedom:

"This is Freedom," I said. "We've spent the last couple of months teaching Freedom the English language. She's an exceptional learner."

She replies:

"Thank you," said Freedom slowly. "Please excuse my grammar as I have only just learned to speak your language. I was born on the fourth of July, so my mother felt like it was the perfect name for a special day."

Bradford asks what the significance of that day is, and Freedom realizes the Pilgrims don't know about that day yet. Before Revere or Freedom can come up with an explanation, a bell rings. The bell means Indians. Bradford points to a lone Indian walking towards a brook by the Pilgrim settlement. Bradford tells the men not to shoot:

"Do not fire our muskets! The Indian walks boldly but he does not look hostile. He is only one and we are many. There is no need to fear. God is with us."

The Indian man has black hair and no facial fair, but

the biggest difference was the fact that the Indian was practically naked. A piece of leather covered his waist but his legs and chest were bare.

He approached the group, smiled, saluted, and said "Welcome, Englishmen!" The wind catches his hair. He surveys the group and sees Freedom's hair moving in the wind, too. He stares at her for a minute and then talks to Bradford, saying "Me, Somoset, friend to Englishmen." Bradford asks how he learned English, and he replies

"Me learn English from fishing men who come for cod"

and then tells them that the harbor is called Patuxet. He says

"Death come to this harbor. Great sickness. Much plague. Many Pokanokets die. No more to live here."

Bradford asks if it was the plague, and Somoset replies

"Yes," said Somoset. "Many, many die. Much sadness. And you. Your people. Much die from cold and sickness. Massasoit knows. Waiting. Watching."

Bradford asks who Massasoit is:

"Massasoit great and powerful leader of this land. He watching you. He knows your people dying. He lives south and west in place called Pokanoket. Two-day journey."

Bradford asks Somoset to let Massasoit know that they (Pilgrims) are his friends. Standish says they have guns, bullets, armor, and cannons, and that they "are here to stay" and hope they can be friends. Samoset says

"Me tell Massasoit. Bring Squanto. He speak better English."

Standish asks who Squanto is, and Samoset says

"Squanto translate for Massasoit. Squanto speak like English man. Help Massasoit and William Bradford together in peace."

Liberty and Revere marvel at what just happened. Liberty wonders about trust, and Revere says Liberty watches too many movies, and that Bradford relied on God's grace to protect them in rough waters and was doing it now, too. Tommy and Freedom offer Somoset a plate of food. Before he takes it,

he reached out to touch the yellow feather in her hair.

She takes it off and offers it to him. He leans toward her and she clips it in his hair. Bradford and Standish wonder if it is safe for him to stay with them overnight. They ask Revere for advice and he tells them that they can't afford to offend Massasoit, and so they agree to let him stay the night. Tommy wonders if Somoset is trustworthy, and Revere tells him that, from everything he'd read, Somoset and Squanto became friends with William, that they realized they could help each other.

Revere, Tommy, Freedom and Liberty are hungry, so time travel to a 50s diner. As they eat, Freedom talks about how hard Pilgrim life was, and Revere tells them that many Pilgrims starved. They return to 1621.

The bell rings and they see five Indians approaching the settlement, led by Somoset, still wearing the yellow father. Squanto steps forward:

"I am Squanto," he said. "I used to live here in Patuxet Harbor. That was many years ago. I've been sent by Massasoit, the sachem and leader of this land. He permits me to come and speak with you. He will come soon. He is eager to meet you."

Bradford asks why his English is so good.

The ease in which Squanto spoke English was unnerving. It didn't seem natural. And yet he was a perfect gentleman as he stood there in his leather loincloth and bare chest.

He doesn't answer, instead talking about sharing of food, and friendship. Somoset gets ready to leave, but before he does, he looks around for Freedom and then gifs her a leather strap with a bear claw attached to it.

Samoset leaves, and Freedom asks Squanto why he and his people left Patuxet Harbor. He replies

"I have heard about the girl they call Freedom," said Squanto. "The girl with midnight hair who speaks perfect English."

She blushes, and, he tells her:

"Seven years ago, I was kidnapped and taken from Patuxet Harbor, never to see my family or loved ones again. I was put on a ship and sailed across the ocean to a new world called Spain. Eventually I sailed to England and learned to speak like you do. Finally I had the chance to travel back to my homeland. I was eager to see my family, my parents and brothers and sisters. But when I returned, there was nothing. Everyone was gone. I soon learned that the plague, a great sickness, had swept over Patuxet Harbor and killed my people."

He pauses, looking into the distance. Freedom and William express condolences. Squanto blinks and a tear rolls down his cheek. He tells them they are kind, and that many of their people died, too, and that the place has "great sorrow" for both Indian and Englishman. But together, he says, they will change that. He will show them how to plant corn.

Revere, Tommy, Freedom, and Liberty travel back to the school where, he thinks, Elizabeth is like Massasoit, that she is "the leader or sachem" of the school, and that students revered or feared her. She watched and waited for signs of weakness in her classmates, or any opportunity to send a message that she was in control of the school. Tommy approaches Revere with a letter that Bradford wanted him to give to Revere. It is an invitation to the "very first Thanksgiving! What an honor!"

Revere, Tommy, Freedom, and Liberty go the the first Thanksgiving. Freedom says "Look at all the Indians." Bradford introduces Revere to "the Indian king, Massasoit" who smiled "and spoke a language that was complete gibberish."

Squanto tells Revere he has a gift for Freedom, and asks permission to give it to her. Revere says it is fine, and that Squanto has been a good friend to Bradford. Bradford says they learned a lot from Squanto, and that

"We believe he's been sent from God as an instrument to help us grow and prosper."

"You are too kind, William," said Squanto. "God, as you say, rescued me from slavery in Spain. The Catholic friars, holy men, helped me escape. They risked their lives to free me so that I could return to my native land. I have much to be grateful for. And I choose to show my gratitude by serving my new friend and holy man, William Bradford."

Later, Revere hears loud shrieks and pounding drums

I turned to see Indians dancing around a fire ring, their faces streaked with paint. Both Indians and Pilgrims smiled as they watched the performing Pokanokets twirl and bend and wave their arms as they sang and chanted to the drums.

They stopped after a while and other Indians whooped and hollered for more. Revere finds Tommy and Freedom. She is wearing a

deerskin dress trimmed with fur and matching moccasins. She also wore a necklace of shimmering shells and two hawklike feathers in her hair.

She tells Revere that Squanto gave her the dress and that

"He said I should be proud of who I am and that I shouldn't care what people think of me. He knows a lot."

The book closes with a note from the author, where Limbaugh writes that Bradford, Standish, Brewster, Squanto, and Samoset were brave and courageous ordinary people who accomplished extraordinary things.