Expressing concern about the spreading problem of book banning and the proliferation of threats to freedom of expression in the United States.

Mr. Schatz (for himself, Mr. Reed, Mrs. Feinstein, Ms. Hirono, Mr. Wyden, Mr. Murphy, Mr. Merkley, Mr. Whitehouse, Mr. Booker, Mr. Cardin, Mr. Sanders, Mr. Durbin, Mr. Padilla, Mr. Markey, and Mr. Blumenthal) submitted the following resolution; which was referred to the Committee on the Judiciary

Expressing concern about the spreading problem of book banning and the proliferation of threats to freedom of expression in the United States.

Whereas the overwhelming majority of voters in the United States oppose book bans;

Whereas an overwhelming majority of voters in the United States support educators teaching about the civil rights movement, the history and experiences of Native Americans, enslaved Africans, immigrants facing discrimination, and the ongoing effects of racism;

Whereas, in 1969, the Supreme Court of the United States held in Tinker v. Des Moines Independent Community School District, 393 U.S. 503 (1969), that students do not “shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate”;

Whereas, in 1982, a plurality of the Supreme Court of the United States wrote in Board of Education, Island Trees Union Free School District No. 26 v. Pico, 457 U.S. 853 (1982), that schools may not remove library books based on “narrowly partisan or political grounds”, as this kind of censorship will result in “official suppression of ideas”;

Whereas the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States protects freedom of speech and the freedom to read and write;

Whereas Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights states that “everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and regardless of frontiers”;

Whereas PEN America has identified nearly 3,400 instances of individual books banned, affecting 1,557 unique titles from July 2022 through June 2023 alone, representing a 33-percent increase in bans compared to the prior year of July 2021 through June 2022;

Whereas of the 2,532 bans in the 2021–2022 school year, 96 percent of them were enacted without following the best practice guidelines for book challenges outlined by the American Library Association, the National Coalition Against Censorship, and the National Council of Teachers of English;

Whereas the unimpeded sharing of ideas and the freedom to read are essential to a strong democracy;

Whereas books do not require readers to agree with topics, themes, or viewpoints but instead allow readers to explore and engage with differing perspectives to form and inform their own views;

Whereas suppressing the freedom to read and denying access to literature, history, and knowledge are repressive and antidemocratic tactics used by authoritarian regimes against their people;

Whereas book bans violate the rights of students, families, residents, and citizens based on the political, ideological, and cultural preferences of the specific individuals imposing the bans;

Whereas book bans have multifaceted, harmful consequences on—

(1) students, who have a right to access a diverse range of stories and perspectives, especially students from historically marginalized backgrounds whose communities are often targeted by thought control measures;

(2) educators and librarians, who are operating in some States in an increasingly punitive and surveillance-oriented environment and experience a chilling effect in their work;

(3) authors whose works are targeted and suppressed;

(4) parents who want their children to attend public schools that remain open to curiosity, discovery, and the freedom to read; and

(5) community members who want free access to a range of uncensored information and knowledge from their public libraries;

Whereas classic and award-winning literature and books that have been part of school curricula for decades have been challenged, removed from libraries pending review, or outright banned from schools, including—

(1) “Brave New World” by Aldous Huxley;

(2) “The Handmaid’s Tale” by Margaret Atwood;

(3) “Anne Frank’s Diary: The Graphic Adaptation” adapted by Ari Folman;

(4) “Their Eyes Were Watching God” by Zora Neal Hurston; and

(5) “To Kill a Mockingbird” by Harper Lee;

Whereas books, particularly those written by and about outsiders, newcomers, and individuals from marginalized backgrounds, are facing a heightened risk of being banned;

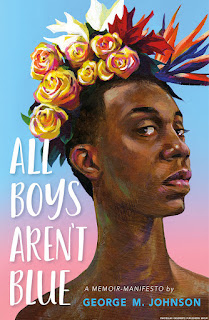

Whereas, according to PEN America, 36 percent of instances of books banned or otherwise restricted in the United States from July 2021 to June 2023 have LGBTQ+ characters or themes that recognize the equal humanity and dignity of all individuals despite differences, including—

(1) “And Tango Makes Three” by Justin Richardson and Peter Parnell; and

(2) “This Book Is Gay” by Juno Dawson;

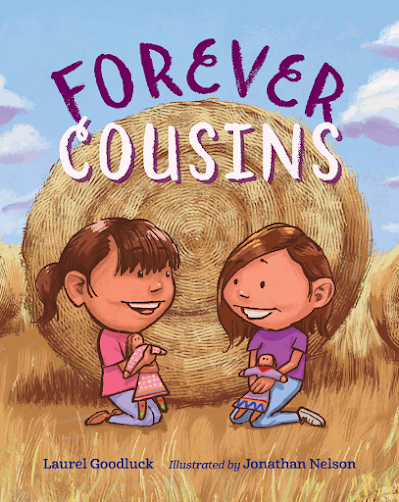

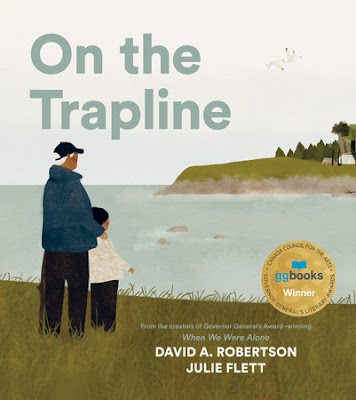

Whereas 37 percent of instances of books, both fiction and nonfiction, that have been banned or otherwise restricted in the United States from July 2021 to June 2023 are books about race, racism, or feature characters of color, including—

(1) “The Story of Ruby Bridges” by Robert Coles and illustrated by George Ford;

(2) “Letter from Birmingham Jail” by Martin Luther King, Jr.;

(3) “Thank You, Jackie Robinson” by Barbara Cohen;

(4) “Malala: A Hero For All” by Shana Corey;

(5) “Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story” by Kevin Noble Maillard;

(6) “Hair Love” by Matthew A. Cherry;

(7) “Good Trouble: Lessons From the Civil Rights Playbook” by Christopher Noxon; and

(8) “We Are All Born Free: The Universal Declaration of Human Rights in Pictures”;

Whereas the Comic Book Legal Defense Fund has reported a dramatic surge in challenges at libraries and schools to the inclusion of graphic novels that depict the diversity of civic life in the United States and the painful and complex history of the human experience, including—

(1) “New Kid” by Jerry Craft;

(2) “Drama” by Raina Telgemeier;

(3) “American Born Chinese” by Gene Luen Yang; and

(4) “Maus” by Art Spiegelman;

Whereas books addressing death, grief, mental illness, and suicide are targeted alongside nonfiction books that discuss feelings and emotions written for teenage and young adult audiences that frequently confront these topics;

Whereas, during congressional hearings on April 7, 2022, May 19, 2022, and September 12, 2023, students, parents, teachers, librarians, and school administrators testified to the chilling and fear-spreading effects that book bans have on education and the school environment; and

Whereas, according to PEN America, from July 2022 to June 2023, States across the country limited access to certain books for limited or indefinite periods of time, including—

(1) Florida, where at least 1,406 books in total have been banned or restricted in 33 school districts;

(2) Texas, where at least 625 books in total have been banned or restricted in 12 school districts;

(3) Missouri, where at least 333 books in total have been banned or restricted in 14 school districts;

(4) Utah, where at least 281 books in total have been banned or restricted in 10 school districts;

(5) Pennsylvania, where at least with 186 books in total have been banned or restricted in 7 school districts;

(6) South Carolina, where at least with 127 books in total have been banned or restricted in 6 school districts;

(7) Virginia, where at least 75 books in total have been banned or restricted in 6 school districts;

(8) North Carolina, where at least with 58 books in total have been banned or restricted in 6 school districts;

(9) Wisconsin, where at least with 43 books in total have been banned or restricted in 5 school districts;

(10) Michigan, where at least with 39 books in total have been banned or restricted in 12 school districts;

(11) North Dakota, where at least with 27 books in total have been banned or restricted in 1 school district;

(12) Tennessee, where at least 11 books in total have been banned or restricted in 5 school districts; and

(13) New York, where at least 6 books in total have been banned or restricted in 3 school districts: Now, therefore, be it

(1) expresses concern about the spreading problem of book banning and the proliferating threats to freedom of expression in the United States;

(2) reaffirms the commitment of the United States to supporting the freedom of expression of writers that is protected under the First Amendment to the Constitution and the freedom of all individuals in the United States to read books without government censorship;

(3) calls on local governments and school districts to follow best practice guidelines when addressing challenges to books; and

(4) calls on local governments and school districts to protect the rights of students to learn and the ability of educators and librarians to teach, including by providing students with the opportunity to read a wide array of books reflecting the full breadth and diversity of viewpoints and perspectives.