|

| A Sample of AICL's Best Books of 2021 |

Those who study and write about children's books will mark 2021 as a significant year because it is the year that Heartdrum (an imprint of HarperCollins) released several books written and illustrated by Native people. Heartdrum's first book,

The Sea In Winter by Christine Day (enrolled, Upper Skagit), is outstanding. We read an advanced copy of it in 2020 and highly recommended it. You will find it below, along with several books we read from Heartdrum. What Heartdrum represents is important. Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee Creek) brought it into existence. For all that she has done, she was named as the recipient of the 2021 NSK Neustadt Prize for Children's Literature. Three of her books were republished this year. In our articles, book chapters, and presentations, we usually include one or more of her books. We're pleased to see the new updated versions and you'll find them listed below.

The persistence of Native peoples who write, speak, and challenge the status quo in other ways is significant. Those who support Native people in that work matter, too. An example is Arthur A. Levine, who launched Levine Querido in 2019. They published Anton Treuer's Everything You Wanted to Know about Indians But Were Afraid to Ask: Young Reader's Edition in April. Last year, they published Apple (Skin to the Core) by Eric Gansworth (Onondaga), which is on the National Book Award Longlist for 2020. It is joined this year at Levine Quierido by A Snake Falls to Earth by Darcie Little Badger (Lipan Apache).

Two topics generated a great deal of conversation in 2021. We mention each one, briefly. First is pretendians, or, race shifting. The identity of writers we have previously recommended has come under question. We are considering how and when we might write about these questions. In the meantime, you can visit our page of resources,

Native? Or Not? A Resource List. The second topic is a growing awareness amongst non-Native people of Native children who died at residential and boarding schools in Canada and the U.S. In June of 2021, reports of hundreds of unmarked graves on the grounds (or nearby) of the schools appeared in news media in Canada, and Interior Secretary Haaland announced an investigation in the U.S. We compiled a list of recommended materials that includes children's books, nonfiction for high school and adult readers, websites, and videos:

Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools. We update those two pages when we find additional resources.

As was the case last year, we are not able to read and write a review of every book we've read. We try! If there is something you want us to take a look at, let us know. Over time we'll be revisiting and adding to the list we share today. As we look over it, we are pleased to see biographies of women of modern times! Though our books are listed below in distinct categories, we encourage you to use picture books with all readers--including adults--and hope that everyone who works with children or books will read all the books. Doing so can help you become better able to know who we are, and that knowledge can help you see stereotyping and misrepresentations.

We hope you order these books for your classroom or school or home library.

--Debbie and Jean

Books Written or Illustrated by Native People

Comics and Graphic Novels

Vermette, Katherena (Red River Metis). A Girl Called Echo, Vol. 4: Road Allowance Era, illustrated by Scott B. Henderson; Colors by Donovan Yaciuk. Highwater Press, Canada.

Board Books

Vickers, Roy Henry (Tsimshian, Haida and Heiltsuk) and Robert Budd, A Is For Anemone: A First West Coast Alphabet, illustrated by Roy Henry Vickers. Harbour Publishing, Canada.

Picture Books

Coulson, Art (Cherokee), Look, Grandma! Ni, Elisi! illustrated by Madelyn Goodnight (Chickasaw Nation). Charlesbridge, US.

Davids, Sharice (Ho-Chunk) with Nancy Mays (not Native). Sharice's Big Voice: A Native Kid Becomes a Congresswoman, illustrated by Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley (member of Wasauksing, First Nation). Harper Collins, US.

Gyetsxw Hetx'wms (Brett D. Huson) (Gitxsan). The Wolf Mother, illustrated by Natasha Donovan (Metis). Portage & Main Press, Canada.

Gyetsxw Hetx'wms (Brett D. Huson) (Gitxsan). The Frog Mother, illustrated by Natasha Donovan (Metis). Portage & Main Press, Canada.

Lajimodiere, Denise (Citizen, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa), Josie Dances, illustrated by Angela Erdrich (Citizen, Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa). Minnesota Historical Society Press, US.

Luby, Brittany (Anishinaabe descent), Mii maanda ezhi gkendmaanh (This Is How I Know), illustrated by Joshua Mangeshig Pawis-Steckley (member of Wasauksing First Nation), translated by Alvin Ted Corbiere and Alan Corbiere (Anishinaabe from M'chigeeng First Nation). Groundwood Books, Canada.

Peacock, Thomas (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe). The Fire, illustrated by Anna Granholm. Black Bears and Blueberries, US.

Robertson, David A. (Member, Norway House Cree Nation), On the Trapline, illustrated by Julie Flett (Cree-Métis). Tundra Books, Canada.

Smith, Cynthia Leitich (Muscogee Nation), Jingle Dancer illustrated by Cornelius Van Wright and Ying-Hwa Hu, Heartdrum, 2021.

Sorell, Traci (Cherokee), Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Golda Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer, illustrated by Natasha Donovan (Métis). Millbrook Press, U.S.

Spillett-Sumner, Tasha (Inninewak (Cree) and Trinidadian), I Sang You Down from the Stars, illustrated by Michaela Goade (enrolled member of the Tlingit & Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska). Little Brown Books for Young Readers, US.

Weatherford, Carole Boston (not Native). Unspeakable: The Tulsa Race Massacre, illustrated by Floyd Cooper (Black and Muscogee). Carolrhoda Books, US.

Early Chapter Books

Quigley, Dawn (Citizen, Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe), Jo Jo Makoons, The Used-to-Be Best Friend, illustrated by Tara Audibert (Wolastoqey). Heartdrum, US.

Smith, Cynthia Leitich (Muscogee Nation), Indian Shoes illustrated by MaryBeth Timothy (Cherokee). Heartdrum, US.

For Middle Grades

Cutright, Patricia (Enrolled member, Cheyenne River Sioux). Native Women Changing Their Worlds. 7th Generation, US.

Engelking, Jessica (White Earth Band of Ojibwe descent). Peggy Flanagan: Omigaakwe, Lieutenant Governor, illustrated by Tashia Hart (Red Lake Anishinaabe). Minnesota Humanities Center, US.

Ferris, Kade (Turtle Mountain Chippewa and Canadian Metis descent), Charles Albert Bender: National Hall of Fame Pitcher, illustrated by Tashia Hart (Red Lake Anishinaabe). Minnesota Humanities Center, US.

Hutchinson, Michael (Misipawistik Cree Nation), The Case of the Burgled Bundle: A Mighty Muskrats Mystery. Second Story Press, Canada.

Smith, Cynthia Leitich (Muscogee Nation). Sisters of the Neversea, cover by Floyd Cooper (Black and Muscogee Nation). Heartdrum, US.

Wilson, Diane (Dakota). Ella Cara Deloria: Dakota Language Protector, illustrated by Tashia Hart (Red Lake Anishinaabe). Minnesota Humanities Center, US.

Young, Brian (Navajo). Healer of the Water Monster, illustrated by Shonto Begay (Navajo). Heartdrum, US.

For High School

Belin, Esther, Jeff Berglund, Connie A. Jacobs, and Anthony K. Webster (editors). The Diné Reader: An Anthology of Navajo Literature. University of Arizona Press, US.

Boulley, Angeline (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians), Firekeeper's Daughter, cover by Moses Lunham, Ojibwe. Henry Holt (Macmillan), US.

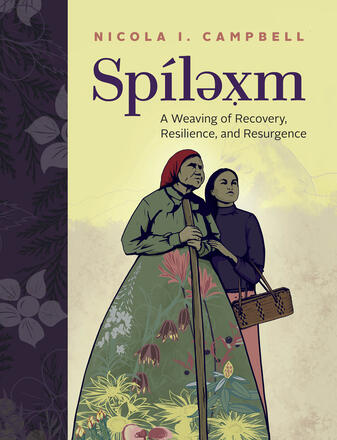

Campbell, Nicola I. (Nłeʔkepmx, Syilx, and Métis). Spílexm: A Weaving of Recovery, Resilience, and Resurgence. Highwater Press, Canada.

Smith, Cynthia Leitich (Muscogee Nation). Rain Is Not My Indian Name, cover illustration by Natasha Donovan (Métis), Heartdrum, US.

Treuer, Anton (Ojibwe). Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask (Young Reader's Edition). Levine Querido, US.

Cross-Over Books (written for adults; appeal to young adults)

Harjo, Joy and Howe, LeAnne (eds.) When the Light of the World Was Subdued, Our Songs Came Through: A Norton Anthology of Native Nations Poetry, cover by Emmi Whitehorse (Navajo), WW. Norton and Company, US.

Peacock, Thomas D. (Ojibwe). Walking Softly. Dovetailed Press, US.

Books Written or Illustrated by non-Native People

Picture Books

Hannah-Jones, Nikole and Renée Watson, Born on the Water: The 1619 Project, illustrated by Nikkolas Smith. Kokila, US.

For High School

Johnson, George M. All Boys Aren't Blue: A Memoir Manifesto. Cover art by Charly Palmer. Farrar Straus Giroux, US.

Kiely, Brendan. the OTHER talk: reckoning with our my white privilege. Simon & Schuster, US.