- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materi...

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

Thursday, April 28, 2022

Highly Recommended: DEB HAALAND: FIRST NATIVE AMERICAN CABINET SECRETARY, by Jill Doerfler and Matthew J. Martinez

Friday, April 22, 2022

Thoughts on David A. Robertson's THE GREAT BEAR being removed from libraries

- The Durham School Board had removed several books that have "content that could be harmful to Indigenous students and families."

- Robertson was stunned and confused to learn that the board had removed his book because its contents could be harmful to Indigenous students.

- An email to principals in the district instructed schools to remove the books, pending a review.

- The email said that schools regularly review collections that are "no longer current, or which may contain content that perpetuates harmful narratives, racial slurs and discriminatory biases, assumptions, and stereotypes." Specific information about the contents deemed "harmful" were not provided.

- Robertson's publisher had attempted to reach the district by emails sent on April 1 and April 6.

"enjoy reading about colonialism, residential school, culture, etc. They live it n don't need to be forced to listen, read n experience colonial-violence."

Friday, April 15, 2022

Debbie Reese responds to Kent Nerburn

On April 13th, the MinnPost ran an interview that Jim Walsh did with me. In it, Walsh asked me what I find most bothersome about the idea of white writers writing Native stories. You submitted a comment in response to what I said and it seems you were hoping I'd see your comment. I tried to reply but had trouble registering for an account. Rather than fuss with the website, I decided to respond here.

By Kent Nerburnon April 13, 2022 at 1:39 p.m.As a non-Native author who writes about experience with Native reality and has done it in a unique way that has gained both respect and traction in Native America, I wonder what Debbie Reese thinks of my work and approach in Neither Wolf nor Dog, The Wolf at Twilight, and The Girl who Sang to the Buffalo? I think I’m an outlier who has found a way to write across cultures, and many Native readers and organizations agree. But I always want to hear other opinions. The books are well-known and used in many curricula, so I’m guessing she knows of them. This forum is an odd way to reach out, but it seems like an opportune way to do so. My apologies if this seems like a self-serving comment; it is not intended to be so. It is a way to expand the dialogue that needs to take place so that people’s voices are heard undistorted, but, at the same time, to explore ways that we can keep from balkanizing ourselves so totally that it becomes illegitimate to reach and speak across cultures.

Native America wants the story of the boarding schools known; Deb Haaland wants the story known; I want the story known. Otherwise, I wouldn't have written the book. We need to seize the moment.

A strong NO to getting his book into anybody's hands. People can learn about boarding schools from Native people. It is long past time that white folks -- however well-intentioned -- stopped speaking for/about us.

And well it should be. And I agree that Native people should tell their own stories. But I suspect that you have not read my books or delved into who I am, what my background is, what I do, and why I do it. With a more open mind and heart you might well see that there are some ways to be an ally that do not represent either cultural appropriation or cultural exploitation. I can only control my intentions; I cannot control the response of people to my work. I respect your concern, but I think perhaps you are seeing through a generic lens, which is exactly what non-Native people have done to Native peoples over the years. Do not make the same mistakes from the other side that have been made from the Euro-American side. We need to be larger than that.

Returning to books: I study the data of what gets published. Maybe you don't know about that data. Here's an infographic of books in 2018. Clearly, white writers get far more books published than we do:

If the 25th anniversary edition of your book had been sent to the Cooperative Children's Book Center in 2018 (your anniversary edition came out in 2019), the staff at CCBC would have put it on the list of books by or about American Indians/First Nations. The infographic shows that 23 of the 3,134 books reflected in the data at that moment in 2018 were categorized as being by or about American Indians/First Nations.

My comments: I assume "the silent ones" in your mind are Native peoples. That dedication was one of many things I noted as I read. I think the dedication echoes a stereotypical way of thinking about Native peoples (as silent, without voice), and that it simultaneously signals to readers that you are a good person doing all you can to help us silent ones. Some find it valorous and see you as a good ally to Native people. As a person who studies representations of Native peoples, I see you as another in a long line of white people who are intent on saving us by speaking for us, by telling our stories for us... I know--there are Native people who do think of you as an ally. I don't.

My thoughts: Showing us that vulnerability invites readers to share that tightness along with you. The way you characterize Native concerns seems to belittle them, and ultimately, feels dismissive. The way you wrote those opening paragraphs works to get readers to ally with you but I want to know more about that project and what the books had in them. Did you let parents and grandparents see what was going to be in the book, before publication? Seems that if you had done that, you wouldn't have gotten blow back. You aren't listed as the author of those two books but you lift them up in these opening passages. It seems you're exploiting that project. It sets this whole phone call in motion. It is the set up for how this book came into being.

My thoughts: Your remarks about traditional elders tell readers that you have knowledge about very traditional elders that others may not. You offer that as a reason why the woman's grandfather won't talk on the phone. Something about this feels off to me but I don't have words for it yet.

My thoughts: Earlier, I noted that you tell us the woman wouldn't give you her name, and now, we are not given the name of the reservation. Because I've read the book, I know that this lack of names matters to the success of your book.

We aren't ever going to know the man's name, because he specifically asks you not to share his information. He just wants YOU to tell his stories because he likes what you did with the Red Road books.

That secrecy might feel respectful to readers but to me, it feels very exploitative of your readers. You've written the foreword and intro in a way to disarm criticisms of what you're doing in this book. The "old man" of the chapter title has a request and you're going to honor that request. He trusts you, and we're supposed to trust you, too. But, I don't! All of it feels too tidy.

The upshot of this secrecy is that your name is the only one we know. You are the one who speaks. You are the one who profits from book and movie ticket sales. Maybe you give some of the profits to a Native organization. If you do, that is likely seen as you being a good guy to Native people. Saviorism.

I've got more notes about your book, but I'll pause there to talk about your book being used in schools.

Teacher to class of juniors and seniors in high school: "Today we're going to start reading Louise Erdrich's The Round House. Erdrich is a member of the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa. She is the owner of Birchbark Books, a bookstore in Minneapolis. Let's take a look at the website for her tribal nation."

The teacher would use present-tense verbs as they talked about Erdrich, her bookstore, and the tribal website. The opportunities for visibility are many! But--the students don't have that opportunity because they're reading your book instead. That bothers me. I imagine you'll say it isn't your fault that they choose you over a Native writer. You're right. It isn't your fault, but I wonder if you've done anything anywhere to help them find Native writers?

I see that Carter Meland has a comment to you at MinnPost (dated April 14, 2022) and that you replied to him. You refer to the "own voices" movement as a necessary corrective but immediately follow up with a "But" that argues for your own space. I wish you would spend more of your words lifting Native writers than arguing for your own voice.

Debbie

Thursday, March 24, 2022

Carter Meland's Call to Read Ojibwe Writers

You know--and I know--that the field of children's literature is changing. That change includes letting go of the Tony Hillerman's and the William Kent Kruegers and so many other white writers who misrepresent Native peoples. Their appropriations and misrepresentations contribute to a cycle of harm. Let's disrupt that cycle. Read Native Writers.

Tuesday, March 22, 2022

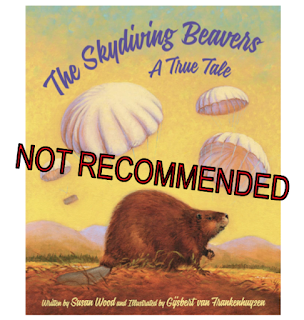

Not Recommended: THE SKYDIVING BEAVERS by Susan Wood, illustrated by Gijsbert van Frankenhuyzen

Just after World War II, the people of McCall, Idaho, found themselves with a problem on their hands. McCall was a lovely resort community in Idaho's backcountry with mountain views, a sparkling lake, and plenty of forests. People rushed to build roads and homes there to enjoy the year-round outdoor activities. It was a beautiful place to live. And not just for humans. For centuries, beavers had made the region their home. But what's good for beavers is not necessarily good for humans, and vice versa. So in a unique conservation effort, in 1948 a team from the Idaho Fish and Game Department decided to relocate the McCall beaver colony. In a daring experiment, the team airdropped seventy-six live beavers to a new location. One beaver, playfully named Geronimo, endured countless practice drops, seeming to enjoy the skydives, and led the way as all the beavers parachuted into their new home. Readers and nature enthusiasts of all ages will enjoy this true story of ingenuity and determination.

Monday, March 07, 2022

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: THE FROG MOTHER

To the Gitxsan of Northwestern British Columbia, Nox Ga’naaw is a storyteller, speaking truths of the universe. After Nox Ga’naaw, the frog mother, releases her eggs among the aquatic plants of a pond, the tiny tadpoles are left to fend for themselves. As they hatch, grow legs, and transform into their adult selves, they must avoid the mouths of hungry predators. Will the young frogs survive to spawn their own eggs, continuing a cycle 200 million years in the making?Book four of the Mothers of Xsan series follows the life cycle of the columbia spotted frog. Learn about why this species is of special significance to the Gitxsan and how Nox Ga'naaw and her offspring are essential to the balance that is life.

This is a "short & sweet" review, listing four reasons AICL recommends this book.

Reason #1 to recommend The Frog Mother: The deep and detailed sense of place.

The author writes about something he knows well: the creatures, environments, and seasons of the homeland of his Indigenous Nation.

He grew up there, in what's currently called inland British Columbia, and learned much of what he knows about the animal inhabitants from elder relatives with both observational and cultural knowledge. (From email communication with the author, 2/2022.) Here's a quote from the book: "As the Gitxsan have borne witness since time immemorial, there is a delicate balance of food for all living in their realm. Nox Ga'naaw and her offspring are an integral piece of this balance that is life." "Since time immemorial." Those are potent words about presence and stewardship!

Reason #2: The illustrations

Natasha Donovan's lively, engaging illustrations are essential to the full impact of the book. And take a close look at each page. Integrated into the depictions of Nox Ga'naaw's life stages, you're likely to see formline images of frogs and other figures. That's the work of the author, placed there to show that the events depicted have spiritual and cultural significance for the people, beyond what might be observed by Western science.

Reason #3: Use of Gitxsan language and knowledge

Seeing words from the Gitxsan language with the English text supports young non-Indigenous readers' awareness that Indigenous languages exist, and have value and purpose. The author refers to animals by their Gitxsan names as well as English identifiers. He uses Gitxsan words for times of the year, which are also listed on a page in the back of the book, along with three paragraphs of information about the Gitxsan and an illustrated map of the region.

Reason #4: The entire series.

The Mothers of Xsan series is based in Indigenous knowledge, but also incorporates what could be called the language of science; many pages include textbox definitions of words like "juvenile" and "overwinter."

Each of these books has deepened my understanding of the ecosystem of the region. Beyond that, I'm reminded of how much impact humans have on what lives around us, and how responsible we are for making our own lives sustain the systems we inhabit. So many young people I know are looking for this kind of understanding, but mainstream society seems built on distancing people from their environments.

Other entries in the series are: The Sockeye Mother, The Grizzly Mother, The Eagle Mother, The Wolf Mother. And due out in 2022: The Raven Mother.

Reading this set of books makes me hope other Indigenous writers and illustrators will collaborate to tell about about the ecosystems of their homelands. The knowledge that could be offered is desperately needed.

Saturday, February 19, 2022

Challenges to AN INDIGENOUS PEOPLES' HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES, FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

address or contain the following topics: human sexuality, sexually transmitted diseases, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), sexually implicit images, graphic presentations of sexual behavior that is in violation of the law, or contain material that might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex or convey that a student, by virtue of their race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.

Saturday, February 12, 2022

Art Coulson and Madelyn Goodnight's LOOK GRANDMA! NI, ELISI! featured in Reading Rainbow Live

Bo wants to find the perfect container to show off his traditional marbles for the Cherokee National Holiday. It needs to be just the right size: big enough to fit all the marbles, but not too big to fit in his family's booth at the festival. And it needs to look good! With his grandmother's help, Bo tries many containers until he finds just the right one. A playful exploration of volume and capacity featuring Native characters and a glossary of Cherokee words.

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Analyzing a Worksheet: "Where Would You Fit In?"

If you scored between 21 and 32, you are ready to move to the New England Colonies! You'll fit right in with those Northerners.

If you scored between 11 and 20, you are right in the middle of the New England and the Southern Colonies. You belong in the Middle Colonies!

If you scored between 0 and 10, the South is the place to be for you. You would make the ideal Southern colonist.

I may be back to share more thoughts later. In the meantime, I welcome your thoughts on this worksheet. Has it or others with similar issues been given to your child? Or to children of your friends, or colleagues? And of course, get a copy of Social Studies for a Better World!

Monday, January 24, 2022

American Indian Library Association Announces its 2022 Youth Literature Awards

|

| Source: https://ailanet.org/2022-aila-youth-literature-awards-announcement/ |

For Immediate Release

January 24, 2022

AILA announces 2022 American Indian Youth Literature Awards

CHICAGO — Today American Indian Youth Literature Award winning titles were highlighted during the American Library Association (ALA) Youth Media Awards, the premier announcement of the best of the best in children’s and young adult literature.

Awarded biennially, the award identifies and honors the very best writings and illustrations for youth, by and about Native American and Indigenous peoples of North America. Works selected to receive the award, in picture book, middle grade, and young adult categories, present Native American and Indigenous North American peoples in the fullness of their humanity in present, past and future contexts.

The 2022 American Indian Youth Literature Award winner for best Picture Book is “Herizon,” written by Daniel W. Vandever (Diné), illustrated by Corey Begay (Diné), and published by South of Sunrise Creative. Herizon follows the journey of a Diné girl as she helps her grandmother retrieve a flock of sheep. Join her venture across land and water with the help of a magical scarf that will expand your imagination and transform what you thought possible. The inspiring story celebrates creativity and bravery, while promoting an inclusive future made possible through intergenerational strength and knowledge.

The committee selected five Picture Book Honor(s) titles including:

- “Diné Bich’eekę Yishłeeh (Diné Bizaad)/Becoming Miss Navajo (English),” written by Jolyana Begay-Kroupa (Diné), designed by Corey Begay (Diné), and published by Salina Bookshelf, Inc.

- “Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Gold Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer,” written by Traci Sorell (Cherokee), illustrated by Natasha Donovan (Métis), and published by Millbrook Press.

- “Learning My Rights with Mousewoman,” written and illustrated by Morgan Asoyuf (Ts’msyen), and published by Native Northwest.

- “I Sang You Down From the Stars,” written by Tasha Spillet-Sumner (Cree and Trinidadian), illustrated by Michaela Goade (Tlingit & Haida), and published by Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, a division of Hachette Book Group.

- “We Are Still Here! Native American Truths Everyone Should Know,” written by Traci Sorell (Cherokee), illustrated by Frané Lessac, narrated by a cast of Cherokee, Navajo, Choctaw and Chickasaw Tribal representation, and published by Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc. / Live Oak Media.

The 2022 American Indian Youth Literature Award winner for best Middle Grade Book is “Healer of the Water Monster,” written by Brian Young (Diné), cover art by Shonto Begay (Diné), and published by Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. When Nathan goes to visit his grandma, Nali, at her home on the Navajo reservation, he knows he’s in for a summer with no running water and no electricity. That’s okay, though. He loves spending time with Nali. One night, Nathan finds something extraordinary, a Holy Being from the Navajo Creation Story – a Water Monster- in need of help. With electric adventure and powerful love, Brian Young’s debut novel tells the tale of a seemingly ordinary boy who realizes he’s a hero at heart.

The committee selected five Middle School Book Honor(s) titles including:

- “Ella Cara Deloria: Dakota Language Protector,” written by Diane Wilson (Dakota), illustrated by Tashia Hart (Red Lake Anishinaabe), and published by Minnesota Humanities Center.

- “Indigenous Peoples’ Day,” written by Katrina M. Phillips (Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe), and published by Pebble, an imprint of Capstone.

- “Jo Jo Makoons: The Used-to-Be Best Friend,” written by Dawn Quigley (Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe), illustrated by Tara Audibert (Wolastoqey), and published by Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

- “Peggy Flanagan: Ogimaa Kwe, Lieutenant Governor,” written by Jessica Engelking (White Earth Band of Ojibwe), illustrated by Tashia Hart (Red Lake Anishinaabe), and published by Minnesota Humanities Center.

- “The Sea in Winter,” written by Christine Day (Upper Skagit), cover art by Michaela Goade (Tlingit and Haida), and published by Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

The American Indian Youth Literature Award for best Young Adult Book is “Apple (Skin to the Core),” written by Eric Gansworth (Onondaga), cover art by Filip Peraić, and published by Levine Querido. The term “Apple” is a slur in Native communities across the country. It’s for someone supposedly “red on the outside, white on the inside.” In Apple (Skin to the Core), Eric Gansworth tells his story, the story of his family, of Onondaga among Tuscaroras, of Native folks everywhere. Eric shatters that slur and reclaims it in verse and prose and imagery that truly lives up to the word heartbreaking.

The award committee selected five Young Adult Book Honor(s) including:

- “Elatsoe,” written by Darcie Little Badger (Lipan Apache Tribe), cover art and illustrations by Rovina Cai, and published by Levine Querido.

- “Firekeeper’s Daughter,” written by Angeline Boulley (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians), cover art by Moses Lunham (Ojibway and Chippewa), and published by Henry Holt Books for Young Readers / Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group.

- “Hunting by Stars,” written by Cherie Dimaline (Metis Nation of Ontario), cover art by Stephen Flaude (Métis), and published by Amulet Books, an imprint of ABRAMS.

- “Notable Native People: 50 Indigenous Leaders, Dreamers, and Changemakers from Past and Present,” written by Adrienne Keene (Cherokee Nation), illustrated by Ciara Sana (Chamoru), and published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

- “Soldiers Unknown,” written by Chag Lowry (Yurok, Maidu and Achumawi), illustrated by Rahsan Ekedal, and published by Great Oak Press.

Members of the American Indian Youth Literature Award jury are AILA President Aaron LaFromboise, Blackfeet Nation, Browning, Montana; Chair Vanessa ‘Chacha’ Centeno, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, Sacramento, California; Co-Chair Anne Heidemann, Mount Pleasant, Michigan; Lara Aase, San Marcos, California; Catherine Anton Baty, Big Sandy Rancheria, Austin, Texas; Naomi Bishop, Akimel O’odham, Tucson, Arizona; Joy Bridwell, Chippewa Cree Tribe, Box Elder, Montana; Erin Hollingsworth, Utqiaġvik, Alaska; Janice Kowemy, Laguna Pueblo, New Mexico; Sunny Day Real Bird, Apsaalooke Crow Tribe, Billings, Montana; and Allison Waukau, Menominee and Navajo, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The American Indian Library Association is a membership action group that addresses the library-related needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Members are individuals and institutions interested in the development of programs to improve library cultural and informational services in school, public, and academic libraries. AILA is committed to disseminating information about Indian cultures, languages, values, and traditions to the library community. https://ailanet.org/