On December 24, I learned that a writer I (Debbie) respect tremendously had been suspended by the Romance Writers of America (RWA). Her name is Courtney Milan. I follow her on Twitter because she's a terrific advocate for accuracy in representation, and for #OwnVoices writers. RWA's action against her included saying she could never hold an office in RWA. It was Whiteness in action.

It has been a week now (today is December 31) and a lot has happened related to RWA's decision to suspend her. For comprehensive coverage of what has unfolded since December 24, I encourage you to read

WTAF, RWA: Courtney Milan Suspended From RWA at Smart Bitches.

That action was taken because Courtney had critiqued the representations of Chinese people in

Too Deep for Tears, a novel by Kathryn Lynn Davis. Davis didn't like what Courtney said. She believes Courtney's words led a publisher to drop a 3-book deal with her. So, she filed a complaint against Courtney. So did one of her friends, Suzan Tisdale (if you click on the WTAF link above, you can find links to the complaints). Their complaints led RWA to take action against Courtney. Enough people objected to their actions that the decision was reversed. But--a lot of damage was done and is, apparently, on-going.

When I learned that Courtney had been suspended for her critique of

To Deep for Tears, I wondered if Davis had written any books with Native content. I looked her up and found out that she's got a two-book series where the main character is Salish. Strike that! The character is Davis's imagining of what a Salish woman in the 1870s would be like... And Davis is so wrong. What she created is stereotypes. I read the first book (initially published in 1990) and tweeted about it as I read.

You'll see some summary (what is happening in the story) and some critique, too. I may come back at some point to say more about

Sing to Me of Dreams. For now, here's brief notes, followed by the tweet threads I did as I read the book. They're lightly edited.

- The Salish people and their lives, in this book, are more like cave people. In fact, it reminds me a lot of Clan of the Cave Bear. I'll note, however, that I read that book 40 years ago, so my recollection might be off. The point is, the Salish people that Davis created are primitive. One example: they don't wear shoes. They go barefoot.

- That primitive characterization means that once the main character starts living with White people, she has a lot of admiration for their things (knives, stoves, etc.)

- A lot of what I read in Sing to Me of Dreams makes me ask Davis about her source. A lot of white anthropologists wrote some highly biased books about Native peoples. In short, I'm giving her room to tell us why she wrote what she did. If we know her sources, we can shed light on their biases and errors. Davis has given her characters personal names and she's inserted what she says are Salish words throughout the book. If there is no source for any of this, then the entirety of the flaws rest on Davis.

- Tanu/Saylah (the main character) is gratingly invested in helping and comforting the White men at the Ivy household. That is possible, but not plausible. All their talk of gold and land and riches is never countered by a single thought from a Native person (Tanu/Saylah) whose people were fighting to protect their lands from the likes of the Ivy men by that time.

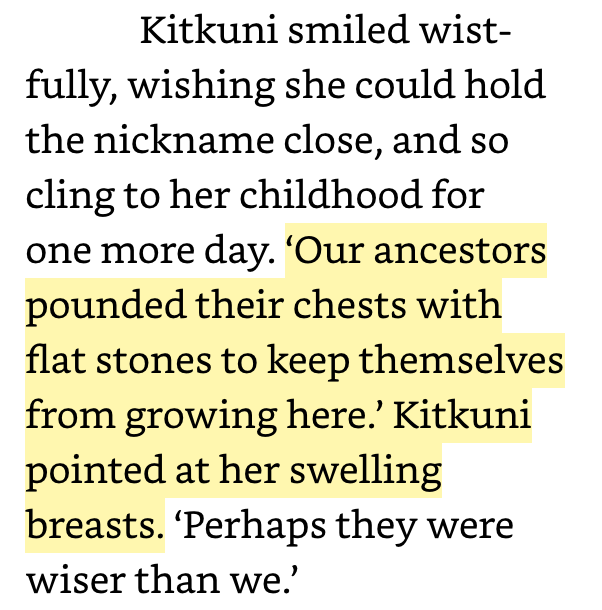

- There's a lot that Davis intends for us to read as Salish ceremonies and world view, but it sounds more like New Age appropriations. And some of it is ridiculous. An example of that is when Tanu and another girl are bathing (they're 15, I think) and one remembers that their ancestors tell them to beat their chests with flat rocks to keep their breasts from growing.

Sing to Me of Dreams, from my point of view, is a mess. In defense of the book that Courtney criticized, Davis and others said she wrote it decades ago. In other words, before anybody knew anything about stereotypes. That is nonsense. What they mean is before they knew anything about stereotypes. Native and People of Color have known about these problems for a very long time. The thing is--the book that Courtney started reading--and the one I critiqued were republished in the 2010s as e-books. Presumably, Davis could have made edits to the books before the e-copies were released. Maybe she did! One would have to get a copy of the originals to do a comparison. If these 2010s editions are revised, I'd really hate to see what she had in the older versions.

I didn't write much about the time during which Tanu/Saylah was at a mission school. I might come back to do that. It won't go well for Davis if/when I do. I bring it up now because when she first wrote this book, she had some knowledge about the boarding schools. She had enough to use one as a decorative plot device in her book. She's tokenized them and what they did--in reality--to Native peoples.

Turning now to larger contexts, I see parallels between what is happening in RWA and what is happening in other associations. In particular, I am thinking about how a small and dedicated group of people have pushed very hard to make the Children's Literature Association (and children's literature) more diverse. We're met with derision by White people. Others want to help, or profess that they want to help, but they stumble over Whiteness. Rules about politeness and professionalism and civility are examples of that Whiteness.

Here's the threads I did. As noted above, I may return to this book with more to say, later.

Thread #1, started at 7:53 AM on December 24th, 2019:

#IStandWithCourtney because she pushes against misrepresentation in romance novels. This morning as I read about this action RWA took against her, I'm reminded of some of the misrepresentations of Native ppls in bks in the genre.

[Background: On Dec 23, 2019, the Ethics Committee of Romance Writers of America recommended that Courtney Milan be censured, suspended, and banned from holding any position of leadership on the RWA National Board or on any of the RWA Chapter Boards based on complaints filed by Suzan Tisdale and Kathryn Lynn Davis. The latter's complaint included objections to Courtney Milan's critique of the Chinese content of Davis's book, Somewhere Lies the Moon.]

My research and writing is on misrepresentations in children's and young adult lit. I sometimes read bks in other genres because someone writes to ask me about a particular bk, and because readers of those genres are also reviewers/buyers/librarians whose work shapes kid/YA lit.

In reading the materials/threads abt RWA/Courtney, for example, someone said they had been a buyer for children's bks before moving on to work in romance. In kid/YA lit we see popular/award-winning writers whose works are racist.

I wondered if Tisdale or Davis wrote bks w Native content. So, I looked.

Davis has a series called Dream Suite.

The first one is SING TO ME OF DREAMS. It came out in the 1990s and again, in 2015. The main character is named "Saylah." Her mother is Salish. Her father is white. It opens in the Pacific NW in 1861.

Davis is not Salish. This is not an #OwnVoices book.

In SING TO ME OF DREAMS we have a white woman imagining Native women in the 1860s. Davis is crossing tremendous distances to create these characters.

The prologue shows me how dreadfully Davis has failed.

In that prologue, "Koleili" is giving birth. "The People crouched outside the hut of woven mats, silent, expectant, for they felt the chill of magic in the air."

My guess is that most ppl won't see "hut" or "crouched" or "magic" as problems.

There's several midwives tending the birth, including "Kwiaha, who had the gift of siwan--the little magic."

The word "siwan" is in italics. I guess we're supposed to think it is a Salish word. Is it? And if it is, does it mean magic?! I doubt it.

The baby is born. The midwives usually splash a newborn with "sacred water to wake her sleeping, unborn soul."

Hmm.... is that how Salish people think of infants in utero?

Before they used that sacred water, however, this newborn opens her mouth and smokes come from it. The hut is filled with soft blue light. This newborn then turns on her stomach, lifts her head and looks at them with "eyes the color of an Island lake - clear, ageless, and wise."

Outside that hut, "the sacred wolves" that are spirits of revered ancestors, make a circle and howl, thereby claiming "the girl child". Owls hoot. The newborn's mother hears the hoot and says her child will be a dreamer.

Raven circles, and "Hawilquolas" (the man who would be father to the child) says "The child will be a Dancer."

"Thunderbird moved through the heavens..." and Kwaiha (the siwan) says "The child will be a healer."

The baby opens her mouth again but instead of a cry, her voice "flows like water, like the silvery music of the birds."

She's "the Prophet" who would bring her people to thrive. The prologue ends with "So it was promised, so it had come to be."

I'm sighing and full of questions as I read this prologue.

The book I'm tweeting about (SING TO ME OF DREAMS), by the way, is by Kathryn Lynn Davis, a writer who filed a complaint about Courtney Milan.

Davis's complaint, and another one from Suzan Tisdale led the RWA's Ethics Committee to take action against Courtney. Over at @SmartBitches, there are links to the docs.

There's people in RWA characterizing Courtney and others who publicly critique books as a "mob." That kind of characterization is said about me and others in kid/YA lit who do public critiques of books.

RWA received enough pushback to their decision on Courtney, that they've rescinded it, "pending a legal opinion." I'm taking a look at Davis's book because she and her bks mattered, somehow, to RWA.

I've now opened (in Amazon's 'look inside') Davis's second book in the Dream Suite. In the Acknowledgements she thanks Suzan Tisdale. She did that in the acknowledgement for the first book, too. I know not to read too much into Acknowledgements but... hmmm.

In bk 2, WEAVE FOR ME A DREAM, the year is 1894. Place is Vancouver Island, British Columbia. No prologue in this one. Instead, there's "The Storyteller." She is "Old Grandmother" weaving at her ancient loom. Weaving stories.

What I'm seeing in Davis's writing is stereotyping.

I think it is accurate to say that she really likes Indians.

That's why she wrote these two books in the 90s and reissued them in the 2010s as ebooks.

But the "Indians" she likes/creates do not exist in real life. This is all romantic nonsense that is harmful to everyone.

There is a defense of Davis over the bk Courtney critiqued, w/ people saying Davis wrote that bk in the 90s. Implied in that defense is that she wouldn't write it today. Implied is that she knows more today than she did then.

Ppl are also saying "nobody said anything" (then).

Those defensive arguments are put forth all the time, but they are not valid.

Davis first published these Dream bks in the 90s and reissued them now, in the 2010s. I can't compare the two, but the ones available now are dreadful.

And the "nobody said anything" defense is so weak!

Maybe people didn't want to make Davis uncomfortable, so they didn't say, HEY THIS IS A MESS.

They let her be.

If they are friends of hers, they aren't very good friends. They've let her republish this deeply flawed series!

If they are friends who did not see the problems, and are reading/learning in this thread, they better talk to her right away. AND they better speak up whenever they see an outsider trying to create characters like this.

Just pause a minute and think about what writers who create historical fiction/romance are trying to do when they're not of the culture or nation that their story is about. They're leaping backwards in time but they're making other kinds of leaps, too. Language is one.

As I read thru Davis's book, I see another italicized word. "Siem." Supposedly, it means "Head Man." What is Davis's source?

I also see that she has created several characters whose names start with a K.

Why?

Another leap: from whatever Davis believes (spiritually or religiously), to what she thinks Salish ways are... And I wonder if Davis would call, for example, Christianity "magic" (in the bk, some of the characters have "magic").

Circling back to the prologue. The baby born in the prologue is called Tanu. The Salish man named Hawilquolas... he's a man of status. He's that "Siem" I mentioned a couple of tweets back. His protection keeps Tanu and her mother from being despised because "... Tanu had been illegitimate, the seed of a stranger. The People would have cast out Koleili and her baby."

Is that accurate? Would Salish ppl of the 1860s do that? As before: what is the source for this information?

I'm remembering Cassie Edwards defending her stories

So anyway, Tanu and her friend Kitkuni are bathing...

‘Our ancestors pounded their chests with flat stones to keep themselves from growing here.’ Kitkuni pointed at her swelling breasts. ‘Perhaps they were wiser than we.’

What is the source for THAT?! I'm not far into the book and it is more and more of this same kind of thing. I'm not tweeting every thing that makes me cringe.

Some may think it is cruel to do that to Davis. The sympathy is for her rather than for readers who are misinformed by what she's written.

Oh... now there's a "Trickster, and, a few pages later, a "shaman."

Over and over there's evidence that this is a not-Salish person creating the words, thoughts, actions of what they think a Salish person would say/do ... and over and over, it is a mess.

Now, Davis's character is calling the shaman's clothing a "sacred ceremonial costume."

Tanu is also called "She Who Is Blessed." And... the people view her as their Queen. Much is made of her green eyes.

Now, Tanu meets her real father. Nicolas. Things about her that are revered, she realizes, come not from her Salish mother, but from her French father.

I am gonna step away from this book. I may pick it up again later but what good would come of doing that?

My larger point is that @romancewriters has at least one writer who is creating harmful content about Native peoples. I'm calling it out. When Courtney Milan called out that author for harmful content, complaints were filed. RWA's ethics cmte decided to censure Courtney Milan.

RWA has some work to do. I'm not a member. If I was, I'd cancel my membership but I'd keep putting public pressure on them, calling for change. Substantial change.

In her complaint, Kathryn Lynn Davis said that she lost the promise of a 3-book contract because of Courtney Milan's "cyber-bullying."

If the 3-bks are like SING TO ME OF DREAMS, then I hope the contract was cancelled because whoever that contract was with said "never mind."

In defense of Courtney's tweets about TOO DEEP FOR TEARS she said that if Courtney had read the whole book, she would see that her objections are wrong.

I'm still rdg SING TO ME OF DREAMS to see if there's anything in here that tells me I'm wrong to object to that passage the Salish girl says about how their ancestors pounded their chests with stones to keep their breasts from growing:

What I usually do in my critiques is to note a passage (like that one) and see if I can figure out what the author's source might be.

It is important to know what sources are--and to say "don't use this" because of unreliable content in some sources. Esp ones about Native ppl.

It is, in short, a service I provide to writers when I do critiques. I do that even when the content in a passage (like that one) is ridiculous because obviously, Davis thought it was legit, and all the ppl who read the bk and didn't say 'wait" to it think it is legit, too.

All of this matters so much! Davis is serving as an editor. If your book has Native content--I hope this thread is telling you that she might not be equipped to help you.

Actually, because she's an editor, I think I'm gonna ask her a question in my next tweet in this thread.

Hey, @kathrynlyndavis: I'm trying to verify information in your bk, SING TO ME OF DREAMS. Can you tell me the source you used for that passage abt Salish ppl using stones to pound their chests?

And, @kathrynlyndavis, can you tell me the source you used for the words you present as being Salish words?

A note for ppl who missed this info in the thread: SING TO ME OF DREAMS was published in the 1990s and again in the 2010s. Here's the two covers:

The first part of Davis's bk is set in a Salish village where Tanu is revered.

There's a gathering (of whites, called "Strangers" in the bk, and Native ppl). The men of the village walk with Tanu in a protective way as the white men gape at her.

But then, intrigued by things, they [the men of the village] "moved barefoot" away from her.

Why are they barefoot? Why point out that they are barefoot?

Then, Tanu sees her mother looking at someone (a white man). She goes to him. They kiss. He is Tanu's biological father.

Later a white man tells the Salish about a missionary school where they will be taught to talk, dress, and act right, "give you all a better life."

He's drunk; the Salish people look at him in "stony or amused silence."

That night as she walks, Tanu hears a song she's heard forever, in her head. This time it is real, and is being sung by her biological father (Nicolas). She's distraught to know that it is "in her blood."

Her voice (remember the prologue?) was what it is, because of her white blood. Her voice, as part of her sacred power, comes from "a Stranger" (white man).

The shaman tells her that she has to find peace with her mixed blood.

They're leaving their summer village for their Longhouse. As she helps she noticed Yeyi (a little girl), trembling.

Later Tanu goes into the forest to find peace with her mixed blood identity. The next day, someone from the village finds her. They need her because Yeyi is sick.

When Tanu sees Yeyi she recognizes what's wrong because the shaman ("Tseikami") had shown her scarlet fever "Red Sweating Sickness" before in a nearby village. Yeyi's family tells Tanu that Yeyi is "ghost-struck" and they want her to send the ghost away. Tanu asks where Tseikami is, and Yeyi's mother tells her that he "packed his rattles, his clothes, and left us."

Tanu thinks he's left because he knows they're all in danger.

Yeyi's mother says that Yeyi will be ok because Tanu "makes miracles" and that nobody "has more spirits than she. Our Queen will do what Tseikami feared to do."

I didn't note it earlier, but "queen" is a European convention. To have these Salish ppl use it is wrong.

There's other examples of what goes wrong when an outsider to a ppl tries to write as if they are an insider. Like, "hut." That's one of my pet peeves. Writers: do some homework! Find out what a ppl called their homes. Don't default to "hut."

I don't think I said anything about how "queen" came about... When Tanu was six years old, the ppl were starving. She had a dream. She and three hunters went out with her on a canoe. She saw a buck, drew her bow, and killed it. But it wasn't a buck!

The people are "struck dumb at the sight of a doe with antlers, which denied her sex and made her more than it was possible to be -- a miracle!" Because that six year old had dreamt of it and then killed it, she was their savior and a queen.

I don't get it.

Anyway, those antlers had been kept by that shaman who took off. They're brought out and placed by the fire. People touch them as Tanu tries to heal Yeyi.

Yeyi's family also gets sick.

Just before she dies Yeyi tells Tanu that the ppl blame Tanu for not freeing them from "the evil spirits" making them sick.

"It is easier to say you are weak than to believe the Changer is so cruel that he would let this happen. If I believe in you, I must doubt him."

The Changer? Who is that?! (Yes, I'm being a bit snarky...)

Just before Hawilquolas dies, he tells Tanu that the people have lost faith in her, and so, she is free, and he wants her to seek peace.

Just before Koleili (Tanu's mother) dies, she tells Tanu it was not an honor for the ppl to view Tanu as a queen. The ppl, Koleili says, did not view her as a person who deserves a husband and children. Kaleili tells Tanu she has to leave.

Tanu is overcome with grief and is weak after tending to so many. She drifts in and out of consciousness, and sees "the Stranger's school."

Tanu leaves. She goes to the mission school where they give her a new name, "Sally Fisher."

She [pretends] can't say "Sally." She can say "Saylah" and so, that becomes her name.

I'm not commenting on all the details I'm including in this thread about SING TO ME OF DREAMS.

At this point in the story (about 1/5th of the way into it), the location changes from a Salish one to a White one. For 3 years, "Saylah" is at the mission school.

Then, she leave the school and goes to live as a caregiver for a white family.

That's where she meets a white man who, according to what I'm seeing, she will marry.

Thread #2, started at 3:25 on December 28, 2019.

Starting a new thread as I read Kathryn Lynn Davis's SING TO ME OF DREAMS.

One thing a lot of writers do that I find annoying: describing eyes of a Native person as "black eyes." That's in here 10 times. She doesn't mean from being hit or injured. She means the iris is black.

And eyes shaped like almonds. That's in here, too. Four times.

Remember in that earlier thread, I noted that Salish men are barefoot? That's so annoying--the idea that Native ppl went without shoes on their feet.

According to what Davis is telling her readers, that's the way the Salish ppl lived.

Here's Saylah (previously, Tanu), talking to the white woman (Flora) who runs the white household Saylah now lives in as a caregiver:

‘I am Salish,’ she explained. ‘I wore no shoes until I joined the missionary school,"

White ppl think Native ppl didn't wear shoes. You can see that in the U of Illinois mascot, "Chief Illiniwek"... see the bare feet? But they needed to protect their hands. See? Look at those gloves.

Nonsense! Whiteness and its nonsense!

Julian is the guy who Saylah is gonna marry. But right now, she's living in the house owned by Julian's father, Jamie. Jamie is bedridden. But, he wants to see Saylah. Julian takes her into his room. She remembers when a girl at the school got the "Red Sweating Sickness."

Remember? That is what (according to Davis), the Salish ppl called scarlet fever.

But, "Red Sweating Sickness" looks to be something Davis made up. The searches I do on that phrase lead to her bk or bks about her bk.

Again, I turn to Davis to ask, @kathrynlyndavis what is your source for that? And--I'll note again that I'm asking this because you are an editor, with the responsibility of helping writers. What sources are you using, and are you recommending them to your writers?

Back to my reading of SING TO ME OF DREAMS. I'm rdg about other white families/characters now, that Julian's family interacts with. There's Edward and his wife, Sophia.

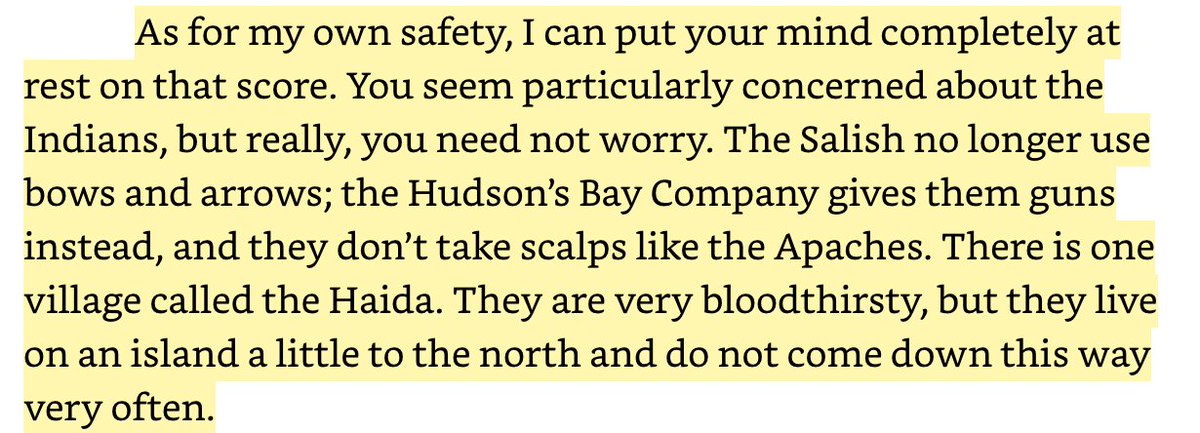

Sophia's dad is in Boston and didn't approve of Edward. He writes letters to Sophia. In one, he writes that he worries she is in danger, "from the savages who people those islands."

As I read on, will Sophia tell her dad they're not savages--that "savage" is a stereotype and embodies bias?

That letter is in chapter 22. In chapter 25, we see Sophia writing back to her father. Her reply is full of deceptions. She's poking him and his sensibilities, on purpose, but I don't know if it works or not. Here's what she said:

Oh! I meant to insert a link to the previous thread right away, and forgot. So... here is the start of that thread.

In that earlier thread, I noted that when she was 6, the little Salish girl killed what everyone thought was a buck but that turned out to be a doe. That was a miracle, they felt, and so they viewed her as their queen (yeah, that is a problem). I bring that up now because that deer makes another appearance when Saylah left the mission school to work for the Ivy family. When she arrives at their property, she sees a tree that has been carved into a buck with antlers. She views it as a sign that tells her she is where she needs to be. In the Ivy household Saylah coaxes Jamie Ivy out of his bed where he's been sick for some time. Julian is his adult son. One evening he tells them all the story of that carved deer. It is symbolic for him, about where he's meant to be.

Where he's meant to be... land that belonged to what tribal nation? Saylah seems unaware of any tribal nation's fight to protect their lands from White people.

Remember--the story Davis tells starts in 1861. By then, the Salish had already met Lewis and Clark and tribal nations in that area had been negotiating with the US for several years.

As depicted in this bk, there's very little contact with Whites until 1876.

Course, the main character of this bk has an absent white father, so.... there's that.

I'm not sharing much, now, as I read through Kathryn Lynn Davis's SING TO ME OF DREAMS.

To refresh: the main char is meant to be a Salish woman abt 19 years old. When she was w/ her ppl (birth to 15), her name was Tanu. W/ whites, it is "Saylah" ("Sally Fisher"). The yr: 1876.

From 15-18 years old, Saylah was in a mission school (her choice to go there when she feels rejected by her people). At 18 she goes to live with the Ivy's a white family who need help. There's a fella, Julian. His father is bedridden. Why, is a mystery.

That father's name is Jamie. His wife is Flora. They have a son, Theron (he's half bro to Julian).

One day Saylah takes Theron out, to teach him how to shoot a bow and arrow. They take two bows that were hanging on the walls in the Ivy home.

They don't have arrows for the bows. So, they're "collecting cedar sticks" to make the arrows.

Hmm... I'm quite skeptical of that!

But anyway, Saylah carves them, adds feathers, and she shoots one, hitting the target. Theron wants her to shoot a squirrel next.

But she tells Theron that it is wrong to do that for fun. The spirits will be angry. She tells him:

"If you are genuinely hungry or the animal threatens your life, then is it allowed. The animals are glad to give up their lives to feed us, the Changer teaches.’"

There's "Changer" again. What is Davis's source for that?

Theron wants to know who Changer is; Saylah tells him Changer is another name for God. She goes into details on animals giving their lives, how it is a gift, but that:

‘perhaps the animals enjoy the chase as much. Just because they must give up their lives does not mean they must do it easily.’"

Sigh. Then, Saylah and Julian talk about hunting with a bow and arrow versus a gun. She wants to show him that a bow and arrow is a better weapon. So they set off into the woods.

But... she decides he needs a beaver skin to hold the arrows in... So off they go to find a beaver.

They find one; she kills it with the bow and arrow. He admires her kill (thru the neck, saving the pelt). But a cougar appears and he raises the bow and arrow, intending to kill it. She stops him because "the cougar was sacred among the Salish."

Julian tells her cougars are dangerous to his people; Saylah realizes she's not with her own people anymore and sort of panics. She comes to, in Julian's arms.

Note: obviously this "Salish" story is far from that [a Salish story] ... it is a white woman's imaginings. Hmm... Julian and Saylah return to the house. No further mention of the beaver, of using its skin. What happened to it?

That proposed use of a fresh beaver skin reminds me of the fresh skunk skins two Indian men wear in LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE.

Meanwhile, Theron (Julian's little half-bro) and Paul (neighbor's boy) are off in the woods. Paul is mad, having seen his dad, Edward, having sex with someone who isn't his mother (her wife).

THEY SEE THE COUGAR! It sees them! They hide in a log.

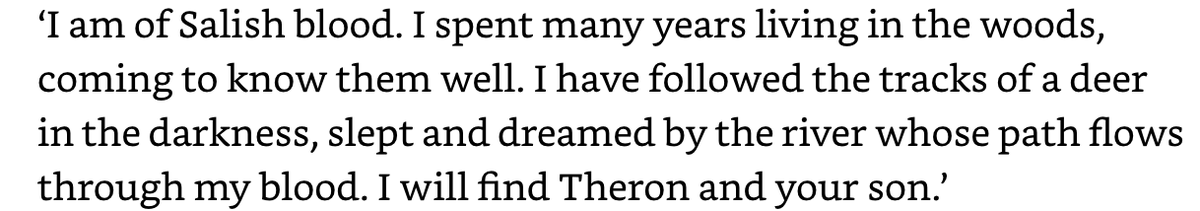

Their parents are worried. It is now nighttime. Saylah sees the parents talking and says she'll go find the boys. Edward asks how she'll do that, in the dark.

She says "I am of Salish blood." (Me, rolling my eyes at this speech.)

Another by-the-way note: whenever this Salish woman speaks, she doesn't use contractions. LOT of white writers create Native speech that way... they think it sounds more authentic. It doesn't.

Saylah and Julian set off into the forest to search for the boys.

They find footprints. When she sees the cougar prints chasing the boys, she panics, remembering she had stopped it being killed.

As they search there's references to "the spirits" who do this or that thing.

Back at the house, Jamie (Julian's sickly father) comes out of his room and waits with the others. He tells them Saylah will find the boys.

Saylah and Julian did find them and have brought them into the house. Saylah will use her herbs to help them. Paul is in shock; Theron has a fever from the cougar mauling his arm.

In case I didn't mention it earlier, Jamie and Edward were friends at one time.

As I've read Davis's book, I've noted her use of Native ppl sitting "cross-legged." It appears six times. Here's one (she's reminiscing):

"Of sitting cross-legged near glowing coals, knee to knee with the other women, the salt air all around us."

It grates, frankly. I've seen that in other bks, too.

Clearly, Davis knows not to use "Indian style." But why does she (or any writer) feel the need to describe how a Native person sits?! If she removed "cross legged" from the sentence, is anything lost? What does having it add?

60% of the way through SING TO ME OF DREAMS. Slow going and not enjoying the reading itself but hope that ppl who write or review bks (no matter what genre) that have Native content are reading, sharing, talking about the errors in the book.

When chapter 48 opens, Paul and Theron (who were attacked by a cougar) are in the stable, afraid to go back into the woods. Paul is envious of Theron's wound.

Theron remembers Saylah saying that her people (Salish) call it "Mark of the Cougar."

Here's a screencap of that part. I've done a search of Salish + "Mark of the Cougar" and found nothing. Seems something that Davis made up, but if you're reading this thread and I'm wrong, Ms. Davis, please tell me! What is your source!

And a very strong caution to writers: DO NOT MAKE UP STUFF YOU THINK NATIVE PEOPLE SAY, DO, OR THINK! You're likely relying on stereotypical ideas you've absorbed. We are real people, of many distinct Native Nations. STOP MAKING STUFF UP! You're misleading readers.

Oh... there's a big party at the Ivy house. Julian is teaching Saylah how to dance (no specific kind of dance is mentioned) and now she's telling him to meet her by the carved deer later so she can "teach you to dance as my People do."

Saylah goes off to dance with Theron. While that happens, Lizzie (a white woman that Julian has had sex with) stands by him and watches him watching Saylah. She says that "Indian women are very mysterious" and that it makes them fascinating. Men can't resist what they don't understand, she says. She moves off and Edward stands with Julian. He's heard what Lizzie said and smiles conspiratorially at Julian, saying that Lizzie s right:

"If we could just find out their secrets, understand them, if you know what I mean, we could resist them."

Earlier in the story, there was a scene where Edward is having sex with a Salish woman.

Still at the party, Edward starts telling the guests about how he and Julian first came to the area... looking for gold. They didn't find much but Julian had guessed it wasn't gold or coal that would make them rich, but the land. Guests cheer as this story is told.

Saylah says and thinks nothing about any of that. Some ppl are probably wondering if I have any suggestions for what Saylah might be saying or thinking, but I don't. Some edits would be easily done (deleting all the sitting cross-legged parts) but the premise is way too flawed.

Way back in the thread I noted that there's tension between Jamie and Edward, and we're learning why now. Back when Jamie was married to Simone (Julian's mom), Edward stole land from Jamie and also had an affair with Simone. As she hears this, Saylah is feeling tremendous empathy for Jamie and what he's lost.

She doesn't have a thought, at all, for the land, or her own people and what they've lost.

I know--that's not the story Davis wanted to tell. What DID Davis want to tell readers?

The party is over and Julian heads to the deer so Saylah can teach him to dance. She leads him deeper into the woods. He's worried about wild animals but she tells him the drums will keep them away.

Drums? Oh...

She's led him to place where she uncovers something. He says it is their old well. But she says:

‘Tonight it is a drum. Usually, you see, there are the drummers and the dancers. I had to think of a way to do both alone. I was lucky to find the well.’

Sounds to me like she's gonna dance on that old well and that her footsteps will make it be a drum, too.

You know what comes to my mind?! This:

She tells him that he said he wanted to know about her people. "This is the most sacred thing I can teach you." He's surprised that dance is that sacred. She tells him it is much more than that:

She says

"Not merely to move to the beat of drums, to the cadence of rattles and the sounds of the night, to change with the firelight, altered every moment by the breeze. To dance, yes, but also to celebrate. That is what I wish to teach you.’

She's made a fire. Now she takes off her coat. He sees she's barefoot, is wearing a necklace of bear and cougar teeth, a top of pounded bark, a cedarbark skirt, and anklets of shell and deer hooves.

She's also brought a bottle of whiskey for him to relax. Now, he takes a drink.

She's dancing, stamping on the well/drum, tapping another drum at her waist. She invites him to join her and feel what she feels, that nothing else in all the world is like it, but that he won't feel it if he's afraid. (This is so weird.)

He's drunk and desires her. She's also singing. He thinks he'll look like a fool if he joins her. Nobody will see, she says. They're alone "with the magic of a Salish campfire and the beat of Salish drums." Watch, she tells him, and his body will know when it is time to join her.

Saylah sings a song (in English). Julian asks about it. She tells him it was Tanu's song, that she was queen of her people but had died long ago. She keeps on dancing (and for me, that image of Tiger Lily is definitely what I see as I read these words of how she's dancing).

Finally, Julian gets on the well/drum with her. He thinks he'll finally have sex with her but, no. He realizes that's not what she's offering. She wants him to join her in "this ritual" which is a glimpse of her true spirit. So, he starts to do what she's doing. He starts to sweat, so takes off his shirt. She puts her bear and cougar tooth necklace on him.

Until now, that cougar that she had stopped him from killing (that later attacked the two boys) had been between them.

But now, it "binds us in his beauty and his rage."

They dance, finally collapse, and sleep (no sex).

Back at the house, it is clear that Jamie is gonna die of a broken spirit, even though everybody (including Saylah) is pleading with him not to give in to that pain.

Later, Saylah tells Julian about Salish ways of understanding death. Again, Ms. Davis: what is your source?

Julian notices that she said "they" and not "we." He understands she's been in pain all this time, too. They kiss but she resists the emotions she feels. Julian tells her she's like Jamie (broken).

In the next chapter, it is nighttime and Edward is having a nightmare. He wakes. Sophia reaches for him but he takes off, down the stairs, out the door, and sure enough, the Indian girl is there, waiting for him. This girl is Salish, too, but to him she has no name.

Saylah knows her, and that her name is Alida (this was earlier in the book). She's described throughout as "girl" but I don't think she's a girl. She's a woman. So, why "Indian girl" over and over?

Anyway, after they have sex she says she's leaving and that she wants him to know her name. She used to feel pleasure when she was with him but lately, she feels more pity than pleasure. She's determined to leave. He tells her that he'll tell her what he did to Jamie if she'll stay.

She isn't going to stay but thinks it will help him with the guilt he carries. So (sigh), she sits crossed legged beside him.

Back at the Ivy house, a priest is there now to give Jamie last rites. Saylah's not cool with it. The priest tells them that Jamie has sins that have to be cleansed so he has a chance to enter heaven.

Saylah tells the priest his religion is strange.

Then she tells him about "the world of the Salish." She challenges him over and over on Catholicism and the family asks him to leave.

I bet ignorant readers think that's a great scene but they likely don't recognize the noble savage stereotyping throughout, and here, too.

Whiteness tends to think of Native ppl as blood-thirsty savages (negative stereotype) or tragic, wise ones (positive stereotype). The latter is the "noble savage" that you see in some mascots, and in "big Indian" statues or "end of the trail" images. (roadsideamerica.com/story/11874)

Ppl tend to think that romantic stereotypes are good--but they aren't. That is something that people need reject. Negative or positive stereotypes are STILL stereotypes that obscure who we are, as people.

Ah, now, this next scene is interesting. Julian is worried because the priest cursed his dad (Jamie). But, Jamie tells him that's an overzealous priest and that others are ok. He talks about the ones that gave comfort to Julian's mom (Simone). Later when Julian and Saylah talk, Julian tells her he hates priests because one took his mother away (literally). Whenever they were around, he says, his mother's joy was gone.

Jamie is dying and tells Saylah he no longer believes in his own faith. Now, he believes in her.

Alida and Saylah--both created as Salish women (by Davis)--to give comfort to white folks.

Jamie dies. At his burial, Saylah sings a song. Is it supposed to be a Salish song, translated into English? Or is it something Davis made up?

Native songs are sung in Native languages. Many (most?) songs are composed, in large measure, of vocables rather than a words.

A few days later, she tells Flora and Theron she wants to burn cedar to cleanse the house of ghosts. They don't want to do that but she persuades them it is a good thing to do. Then she sings and waves singed cedar boughs around.

Sigh (again).

Almost done! At the 90% mark of this book.

Saylah and Julian are in the forest. He tells her he loves her; wants her to say it back but she doesn't want to because it'll make her feel vulnerable and open to hurt again like when her ppl turned away from her. She gives details:

He realizes she's Tanu. "You were their queen."

He tells her they needed her to be that for them, and that he needed her to be"a gift from God" for him. But now, he sees her as a woman who is dear to him, not for her magic or wisdom but for her heart. All through this scene she can hear drums pounding (in her head) and an ancient song. They are loud "endless, throbbing drums." But then, the song ends and the drums fade.

She goes to him and says "I am Saylah. And I love you."

They return to the house. The next morning she wakes and looks at Julian, thinking that if she chooses him, she has to chose his world, too. "the white world, the world of the Strangers."

In the final chapter Saylah goes back to her ppl. She doesn’t see them for real. She falls asleep and the Salish guy who had wanted to marry her finds her. She doesn’t wake but there’s communication going on. He releases her and she goes back to Julian. End of story.

I guess they will marry in the sequel. I will pull all these tweets into a blog post as a record of what I said and try to make some overall observations that I hope will be helpful to writers, editors, reviewers... no matter the genre.