Classic and award-winning books of historical fiction suggest---powerfully---that American Indians were primitive people. Through these books, children are allowed to think that Indians were less-than-human. Primitive in lifestyle. Primitive in intellect.

But, that is not the case.

Here's a few facts to consider next time you read Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie.

Charles took his family into "Indian Territory" in 1868.

By then, about 800--yes, that's right 800--treaties had been negotiated between the tribes and the federal government.

Let's think about that word a minute...

"Treaty."

Treaties are legal documents. They are contracts whose terms are negotiated between two (or more) states.

In order to enter into a treaty, one state has to recognize the other as a state.

States are entities comprised of people with territories that are recognized by the other state, and, these state entities have systems of government. Both states have leaders who enter into diplomatic negotiations.

So. Laura Ingalls Wilder is giving you an image of Indians that is a disservice and an insult to who they were. I think you could say she does you (the reader) a disservice, too, leading you to believe something that is not true.

She isn't solely responsible for this disservice. She had help in preparing her manuscripts. And, she had an editor, too.

You might want to take a few minutes to peruse lesson plans teachers use when they teach this book in their classrooms. If you find one that challenges the ways that American Indians are depicted, let me know! I'd love to see one. Is there a lesson plan out there, that helps children see the errors in these images?

.

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materi...

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query little house. Sort by date Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by relevance for query little house. Sort by date Show all posts

Saturday, February 16, 2008

Monday, July 18, 2011

AICL reader on McClure's THE WILDER LIFE

Editor's Note: Today's post is by a Teacher Librarian, NW of Chicago. She writes:

I have spent a long time pondering your comments about the Laura Ingalls Wilder books because, as you can guess, I loved the books when I read them as a child. However, something happened that put everything in perspective for me. I recently listened to the audio book, The Wilder Life: my adventures in the lost world of Little House on the Prairie, written by Wendy McClure. It is a memoir recording her year of visiting all the places Laura had lived and how she felt about the experience. As a Little House fan, I was riveted. I thought that throughout the book, McClure did an adequate job of pointing out Wilder's prejudices when writing about the Indians. However, toward the end of her book, McClure wrote of this incident:

I have spent a long time pondering your comments about the Laura Ingalls Wilder books because, as you can guess, I loved the books when I read them as a child. However, something happened that put everything in perspective for me. I recently listened to the audio book, The Wilder Life: my adventures in the lost world of Little House on the Prairie, written by Wendy McClure. It is a memoir recording her year of visiting all the places Laura had lived and how she felt about the experience. As a Little House fan, I was riveted. I thought that throughout the book, McClure did an adequate job of pointing out Wilder's prejudices when writing about the Indians. However, toward the end of her book, McClure wrote of this incident:

p. 318In my mind, the incident was a totally "unfitting" way to end the book. This scene ruined my empathetic feelings toward the author and illustrated how Wilder's stereotypes are still alive and well.

I bought a sunbonnet at the museum store, my sixth one.

"I had a feeling you would buy one on this trip," Kara said, as we walked back out to the car. "I bought something, too." She went through her bag in the backseat and pulled out a feathered headband, the kind they used to sell in dime stores for playing cowboys and Indians. "Picture time!" she said.

I started laughing. "Oh my God," I said. "Yes!" We put on our mythical headgear and took pictures of ourselves standing together in the parking lot. It seemed a fitting way to end the trip.

Wednesday, July 15, 2015

About Jane Resh Thomas and Hamline University's Writing Program

This week, Hamline University's MFA in Writing for Children and Young Adults is holding its one week residency. On July 13th, Jane Resh Thomas gave a lecture there.

Based on what I read at On Kindness, On Intention, and On Anger in Children's Writers by V. Arrow, Thomas's remarks were primarily about race. As I read responses--online and privately--to what she said, I have several thoughts.

As a Native woman and mother, I ask that you set aside your feelings of discomfort. Instead, I'd like you to think about the millions of children of color, and Native children, who've read horrible things about themselves in the thousands of books that white writers have written.

Did you know, for example, that Little House on the Prairie has "the only good Indian is a dead Indian" in it three times? Can you imagine how a Native child feels reading that line?

Let me tell you. A few weeks ago, a young Native boy visiting me saw that book on my table. His eyes widened and his voice rose as he said:

It is uncomfortable for writers who read criticism of their work that points out that ideas and words they've carried in their head all their lives is problematic. These ideas and words appear on the page as a norm for one of their characters. For some, having it pointed out to them generates a huge feeling of embarrassment. For others, there is a defensive reaction, too.

As I read V. Arrow's post, knowing that she was in that room as a student--that she is someone who wants to be a writer of children's books--I knew that she took a great risk in writing her post. As I read through twitter conversations about what she shared, I was glad to see established writers like Anne Ursu and Laura Ruby thanking her for that post. Later, Mary Rockcastle (the director of the program) issued this statement:

The stakes are high for Hamline, but they're far higher for the children and young adults who will read the books Hamline students write. It is 2015. For over one hundred years, people have been objecting to the ways that people of color and American Indians are portrayed in children's books. This is not new to me and others who have studied children's literature, but to far too many people, it is a new discussion because it is beyond the spaces they spend their time in.

Hamline can bring it into that space.

Every intervention individuals and institutions make is absolutely vital so that we all get to a point in time when all children can read books that are free of the noise and pain of ignorance, intolerance, and denial in the larger world that intentionally, or not, denies our existence and humanity.

_______________

For further reading:

MFA vs POC, by Junot Diaz, April 30 2014

On Being a Person of Color in an MFA Program, by Justine Ireland, July 13 2015

Based on what I read at On Kindness, On Intention, and On Anger in Children's Writers by V. Arrow, Thomas's remarks were primarily about race. As I read responses--online and privately--to what she said, I have several thoughts.

One: she gave voice to concerns of white writers who feel threatened by the new (to some) and renewed interest in the accurate representation of people who are not white.

Two: she gave voice to concerns of white writers who feel threatened by the new (to some) and renewed interest and commitment to publish writers who are not white.Discussions on social media are evidence that people were clearly uncomfortable with what Thomas said. Was she, herself, uncomfortable as she delivered that lecture? Does she, today, feel unfairly criticized by what people are saying? Are you a white writer who agrees with what Thomas said? Do you think the criticism directed at her, today, is unfair? Mean, perhaps?

As a Native woman and mother, I ask that you set aside your feelings of discomfort. Instead, I'd like you to think about the millions of children of color, and Native children, who've read horrible things about themselves in the thousands of books that white writers have written.

Did you know, for example, that Little House on the Prairie has "the only good Indian is a dead Indian" in it three times? Can you imagine how a Native child feels reading that line?

Let me tell you. A few weeks ago, a young Native boy visiting me saw that book on my table. His eyes widened and his voice rose as he said:

Is that Little House on the Prairie? I had to quit that book.He shook his head a bit as he talked about the Indians stealing furs. And then his voice got even louder when he said

That part where it says 'the only good Indian is a dead Indian? That's when I really had to quit that book!!!It is for that child, and millions of other children like him, that I do the work I do on my site and in my lectures and workshops.

It is uncomfortable for writers who read criticism of their work that points out that ideas and words they've carried in their head all their lives is problematic. These ideas and words appear on the page as a norm for one of their characters. For some, having it pointed out to them generates a huge feeling of embarrassment. For others, there is a defensive reaction, too.

As I read V. Arrow's post, knowing that she was in that room as a student--that she is someone who wants to be a writer of children's books--I knew that she took a great risk in writing her post. As I read through twitter conversations about what she shared, I was glad to see established writers like Anne Ursu and Laura Ruby thanking her for that post. Later, Mary Rockcastle (the director of the program) issued this statement:

Our MFAC program at Hamline is committed to creating a truly diverse and inclusive community. Where ALL of our students can create and do their best work without the noise and pain of ignorance, intolerance, and denial in the larger world that gets in the way.

A faculty member's words yesterday sent the absolute wrong message about how we should deal with each other's anger and pain--as a community and as a culture. It is unacceptable to deny, denigrate, minimize or otherwise deepen this pain.

Our goal is to educate each student about how this happens, how we purposefully or unintentionally get it wrong, so it does not happen again. So the community we've been building learns, grows, and prevails.I gather that everyone was required to attend Thomas's lecture and that there were others that they could choose from. I hope that the program selects someone to deliver a required lecture each residency term--a lecture that takes up this moment at Hamline. It was one moment--one hour in a day--but it was far more than that. For Hamline, the stakes are high right now. I read tweets from people who said they were crossing Hamline off the list of writing programs they're applying to.

The stakes are high for Hamline, but they're far higher for the children and young adults who will read the books Hamline students write. It is 2015. For over one hundred years, people have been objecting to the ways that people of color and American Indians are portrayed in children's books. This is not new to me and others who have studied children's literature, but to far too many people, it is a new discussion because it is beyond the spaces they spend their time in.

Hamline can bring it into that space.

Every intervention individuals and institutions make is absolutely vital so that we all get to a point in time when all children can read books that are free of the noise and pain of ignorance, intolerance, and denial in the larger world that intentionally, or not, denies our existence and humanity.

_______________

For further reading:

MFA vs POC, by Junot Diaz, April 30 2014

On Being a Person of Color in an MFA Program, by Justine Ireland, July 13 2015

Labels:

Hamline University,

Jane Resh Thomas,

V. Arrow

Sunday, August 14, 2016

A few words about Louise Erdrich's MAKOONS

Louise Erdrich's Makoons came out a few days ago. On August 13th, I took a look at Amazon, and saw that it was their #1 New Release in their Children's Native American Books category.

Erdrich is Ojibwe. The characters in her story are, too, which makes Makoons and the other books in the Birchbark House series an #ownvoices book (the #ownvoices hashtag was created by Corinne Dyuvis).

I love the series. I read the first one, Birchbark House, when it came out in 1999.

Birchbark House began in 1866 when we met Omakayas, a baby girl whose "first step was a hop" (page 5 of Birchbark House). Omakayas is an Ojibwe word that means Little Frog. Makoons is the 5th book in the Birckbark House series. In the 4th one, Chickadee, we met Omakayas as an adult with twin sons, Chickadee, and Makoons. I've got Makoons open and started reading it, but after reading the prologue, I'm pausing to remember the other books and characters. The books and the characters in them live in my head and heart for many reasons.

When my daughter was in third grade, her reading group started out with Caddie Woodlawn but abandoned it because of its problematic depictions of Native people. The book they read instead? Birchbark House. One of their favorite scenes from the book is when Omakayas has gone to visit Old Tallow to get a pair of scissors and has her encounter with a mama bear and her bear cubs. Indeed, they wrote a script and performed that chapter for their class (and of course, parents!). My daughter played the part of Omakayas. The prop she made for their performance is the scissors in their red beaded pouch. I've got them stored away for safekeeping. They represent my little girl speaking up about problematic depictions.

~~~~~

Chickadee is captured in Chickadee. The story of his capture and his return is what Chickadee is about. Makoons was devastated by that capture. The worry over his brother makes him sick. That sickness is where Makoons opens. In the prologue, Makoons is recovering as he listens to Chickadee sing to him. They spend hours together. Makoons remembers, and tells Chickadee about, a vision he had while sick. Their family will not return to their homeland. They're going to be strong and learn to live on the Plains but they will, Makoons tells Chickadee tearfully, be tested. The two boys are going to have to save their family... but won't be able to save them all.

A gripping and heartbreaking moment, for me, as I start reading Makoons.

Labels:

Birchbark House,

Louise Erdrich,

Makoons,

Pub year 2016

Thursday, November 29, 2012

THIS AMERICAN LIFE: "Little War on the Prairie", THE DAKOTA 38, and resources for teaching about the US-Dakota War of 1862

On November 23, 2012, This American Life devoted an entire show to a single topic. Titled Little War on the Prairie it is a well-executed look at the ways that people tell a state's history, leaving out things they find inconvenient, or troubling in some way.

The segment opens with John Biewen, a guy who grew up in Mankato, and, who because of the liberal leanings of his parents, knew about racial injustice in the south. He had no idea, however, of the racial injustice in Mankato's history. "Why don't we talk about it?" he asks.

To the credit of Ira Glass, Little War on the Prairie gives us a chance to talk about it. The "it" is the largest mass execution in U.S. history. And like The Little House on the Prairie, a lot is left out of the way the U.S. Dakota War is presented in most histories.

In the piece, Biewen talks with Gwen Westerman. Gwen is Dakota and teaches at Minnesota State University. I know Gwen personally. We were on a panel together several years ago on Representations in Art, Literature, & Cultural Production.

Biewen and Gwen drive to several sites in the area, and they critique what they read and see, and equally significant, they talk about what they do not read and see, and why.

Their dialog is stark and poignant, as it should be, given what they are discussing.

Towards the end of the segment, Biewen talks to some senior girls in high school to see what they know about the Dakota War. Two of them know about the execution. But he also talks to a third-grade teacher, asking her how she presents the War of 1862. Here's her response:

I would like to know what else she said, and I'd really like to know how she feels now, after having listened to the entire segment, which I assume she did. Some listeners may feel she was mis-used by Biewen for this program. If she was not aware of the totality of the segment, I feel bad for her, but I feel far worse for the children who--instead of being taught about Dakota people who had been engaged in diplomatic treaty negotiations with the U.S. government--are being taught that Indians were violent and don't know how to use words to solve conflicts.

I encourage teachers and librarians to listen to Little War on the Prairie, or, read the transcript. And then, apply what you learn to how you teach about the U.S. Dakota War, and how you select and deselect books about it.

I also encourage you to visit the U.S. Dakota War website of the Minnesota Historical Society, where they've put together resources you can use, including an annotated treaty. Here's their introductory video:

At their website, there's also an annotated letter, written in Dakota, by Mowis Itewakanhdiota, a Dakota man who was imprisoned after the war. Thirty eight men were executed, while many more were sentenced to life in prison in Davenport, Iowa. In his letter, Itewakanhdiota writes that he and the other prisoners of war have heard that Lincoln was assassinated. It was Lincoln's intervention that sent some men to prison rather than execution, and they are worried that Lincoln's death may have ramifications for their own lives. (A thumbnail of the letter is on the right side of the page. Click on it to see a larger image; hovering over the red circles on the left side, a box will appear with the text in Dakota and English).

Given the resources available, there is no reason why biased history of this war should continue to be taught. Here's a feature-length documentary about the execution:

Please share the link to this page with teachers and librarians. Let's be honest in how we tell history. Let's, as Biewan asked us to do, talk about it. All of it.

The segment opens with John Biewen, a guy who grew up in Mankato, and, who because of the liberal leanings of his parents, knew about racial injustice in the south. He had no idea, however, of the racial injustice in Mankato's history. "Why don't we talk about it?" he asks.

To the credit of Ira Glass, Little War on the Prairie gives us a chance to talk about it. The "it" is the largest mass execution in U.S. history. And like The Little House on the Prairie, a lot is left out of the way the U.S. Dakota War is presented in most histories.

.......................................................................................................................

"It" is the largest mass execution in U.S. history.

.......................................................................................................................

Biewen and Gwen drive to several sites in the area, and they critique what they read and see, and equally significant, they talk about what they do not read and see, and why.

Their dialog is stark and poignant, as it should be, given what they are discussing.

|

| Image from the June 30, 2012 edition of the Twin Cities Pioneer Press |

Towards the end of the segment, Biewen talks to some senior girls in high school to see what they know about the Dakota War. Two of them know about the execution. But he also talks to a third-grade teacher, asking her how she presents the War of 1862. Here's her response:

We just talked about, like a conflict is a disagreement. And we talked how the Dakota Indians didn't know how to solve their conflicts. And the only way they knew how to solve their disagreements was to fight, which we know we don't fight when we solve conflicts, we use our words.

But that was their only way that they knew how to solve a conflict, they fought. And so then the white settlers needed to fight back to protect themselves. And we talked about people were killed. And then we talked about how the Dakota Indians were-- [FADES OUT]

I would like to know what else she said, and I'd really like to know how she feels now, after having listened to the entire segment, which I assume she did. Some listeners may feel she was mis-used by Biewen for this program. If she was not aware of the totality of the segment, I feel bad for her, but I feel far worse for the children who--instead of being taught about Dakota people who had been engaged in diplomatic treaty negotiations with the U.S. government--are being taught that Indians were violent and don't know how to use words to solve conflicts.

I encourage teachers and librarians to listen to Little War on the Prairie, or, read the transcript. And then, apply what you learn to how you teach about the U.S. Dakota War, and how you select and deselect books about it.

I also encourage you to visit the U.S. Dakota War website of the Minnesota Historical Society, where they've put together resources you can use, including an annotated treaty. Here's their introductory video:

At their website, there's also an annotated letter, written in Dakota, by Mowis Itewakanhdiota, a Dakota man who was imprisoned after the war. Thirty eight men were executed, while many more were sentenced to life in prison in Davenport, Iowa. In his letter, Itewakanhdiota writes that he and the other prisoners of war have heard that Lincoln was assassinated. It was Lincoln's intervention that sent some men to prison rather than execution, and they are worried that Lincoln's death may have ramifications for their own lives. (A thumbnail of the letter is on the right side of the page. Click on it to see a larger image; hovering over the red circles on the left side, a box will appear with the text in Dakota and English).

...................................................................................................................................................

Given the resources available, there is no reason why biased history of this war should continue to be taught.

...................................................................................................................................................

Given the resources available, there is no reason why biased history of this war should continue to be taught. Here's a feature-length documentary about the execution:

Please share the link to this page with teachers and librarians. Let's be honest in how we tell history. Let's, as Biewan asked us to do, talk about it. All of it.

Saturday, September 19, 2020

Not Recommended: Conrad Richter's THE LIGHT IN THE FOREST

The Light in the Forest

Written by Conrad Richter

Published in 1953

Publisher: Alfred A. Knopf

Reviewer: Debbie Reese

Review Status: Not Recommended

****

More than once over the years, someone has written to ask me about Conrad Richter's The Light in the Forest. Given its age (published in 1953), I suspected it would have problematic content and I suppose I didn't have the energy at the moment to do anything with it. Last week, I decided to give it a try. As you see by red X on the three book covers above, my initial suspicions were correct. The Light in the Forest is not recommended. The cover on the right is the spin off version that came out when Disney turned Richter's book into a movie in 1958. A fraud--Iron Eyes Cody--was the "technical advisor" for that film.

I read the acknowledgements and chapter one of Richter's book and did a series of tweets as I read. I'm copying them here:

In the acknowledgements, Richter says he was struck by stories of white captives who had been returned to their white families, but who wanted to run away to rejoin the Indian home where they'd lived.

As a small boy, Richter wanted to run away to live "among the savages."

The acknowledgement is romantic (and stereotypical) in tone. It says Indians were repelled by American ideals and restrained manner. I don't know what ideals Richter had in mind but "restrained" on the heels of "savages" might be a hint of what is to come as I read the book.

The main character is 15. He's white and has been living with Indians as an adopted son since he was 4. The village has received word that they must give up their white prisoners.

He is shocked that it includes him.

Cuyloga (the Indian man who adopted him) had "said words that took out his white blood and put Indian blood in its place." He was thereafter called True Son.

I'm always curious as to how a writer comes up with a Native name for a character. I looked up Cuyloga...

... and got hits to Sparknotes and Cliffsnotes and gradesaver and enotes and quizlet and coursehero.... all of which tell me the book is used a lot in schools.

I think we're meant to think that "Cuyloga" is a Lenape word. The people in this village would probably speak Lenape. But Cuyloga gave this white child he adopted an English name: "True Son." I wonder if Richter will use "True Son" throughout, or if he'll use a Lenape name?

In the first para of ch 1, we learn that Cuyloga taught True Son to "endure pain." True Son holds a hot stone from the fire "on his flesh to see how long he could stand it." In winter, Cuyloga sat smoking on the bank while True Son sat in the icy river till Cuyloga said ok.

True Son doesn't want to be returned to the whites, so he blackens his face (why?!) and hides in a hollow tree. But, Cuyloga finds him. True Son is "tied up in his father's cabin like some prisoner to be burned at the stake."

Burned at the stake?! Again,

Cuyloga takes True Son to the soldiers nearby. True Son resists, which embarrasses Cuyloga. He leaves and True Son imagines their village and its "warriors and hunters, squaws, and the boys, dogs and girls he had played with."

Squaws?

I've read enough of Richter's THE LIGHT IN THE FOREST to know I will be asking people not to use it. It is old, stereotypical, and there are better choices. If the goal is to study conflicts between Native and White people, Erdrich's BIRCHBARK HOUSE is much better!

Today I'll expand a bit on some of what I noted in those tweets.

Richter's idea that Native people teach their kids how to "endure pain" is something I see a lot. I've not traced that down to see where it came from and I'm not doing it now. Certainly, Native and non-Native parents in the past and in the present, teach their kids things they need to know to live. But come on: pulling a stone from a fire and putting it on your flesh... that would cause injury! It doesn't make sense to me.

That "burned at the stake" bit is also a common occurrence and it, too, makes me wonder where it came from. If you've watched old westerns--or even new things like the television series of Little House on the Prairie--you've seen Indians tying someone at a stake and then lighting a fire to burn them alive. You probably remember that Europeans did that to people they thought were heretics or witches. (There's another popular trope that isn't in Richter's book but that you should be wary of: that a captive would be cooked alive in a pot and then eaten.) From what I can tell there's one incident of a white person being "tied to a stake" and tortured. That's William Crawford and I'll be doing research on that to see what I find. I welcome your research into all this, and if you find things of note, let us know in a comment.

I noted that "True Son" uses the word "squaw." A search of the text indicates it appears 20 times. Reading those passages, it is clear that "True Son" has a derogatory view of women, Native or otherwise. Richter's story depicts them as a beast of labor whose work is beneath that of a man.

The word "Injun" eleven times, and scalp (or variations of it) appear 43 times. The emails I get from teachers who want to use the book... now, they make me cringe. Obviously the book is a lot like Little House on the Prairie: holding quite a solid space in peoples' reading memory, coupled with the idea that this is a good book. It is not. I do not recommend it.

Wednesday, March 06, 2019

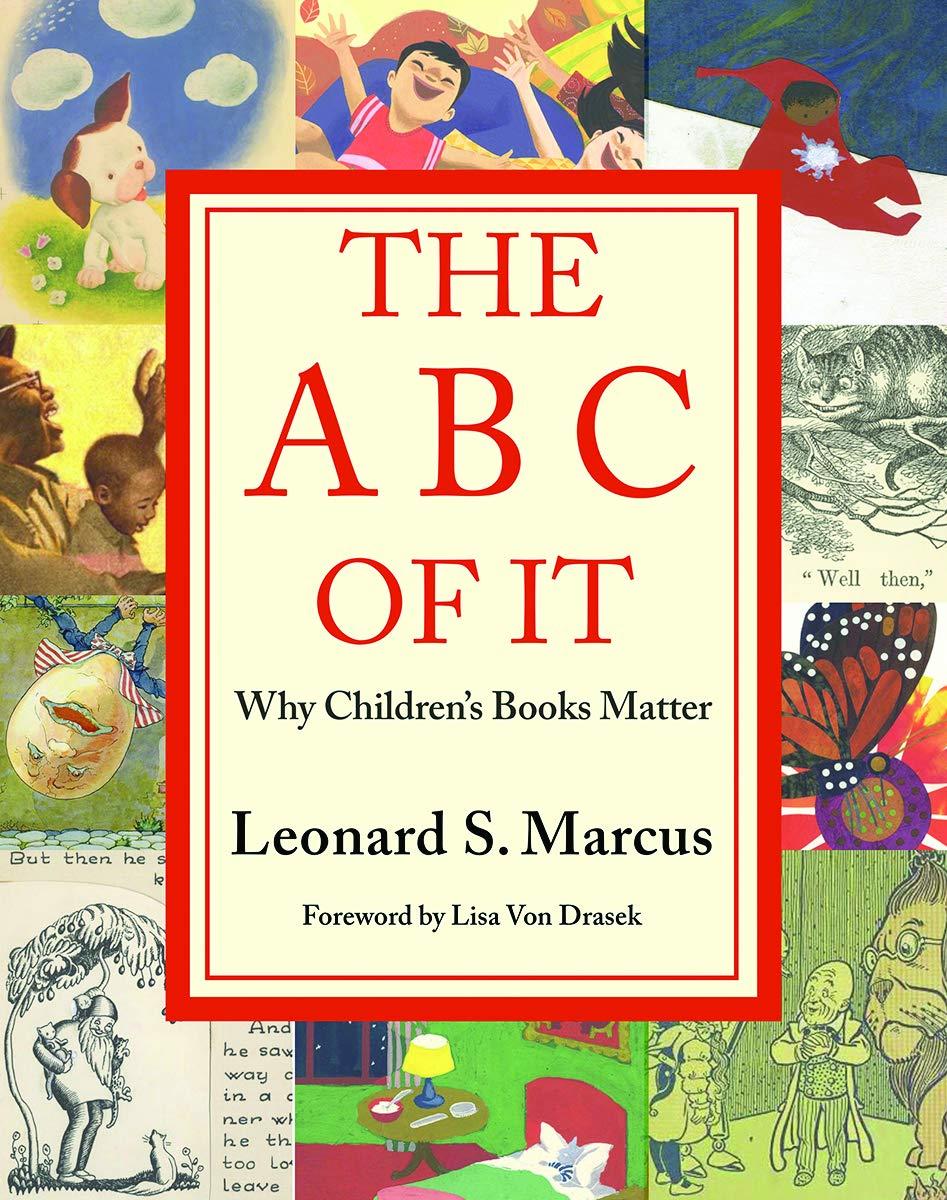

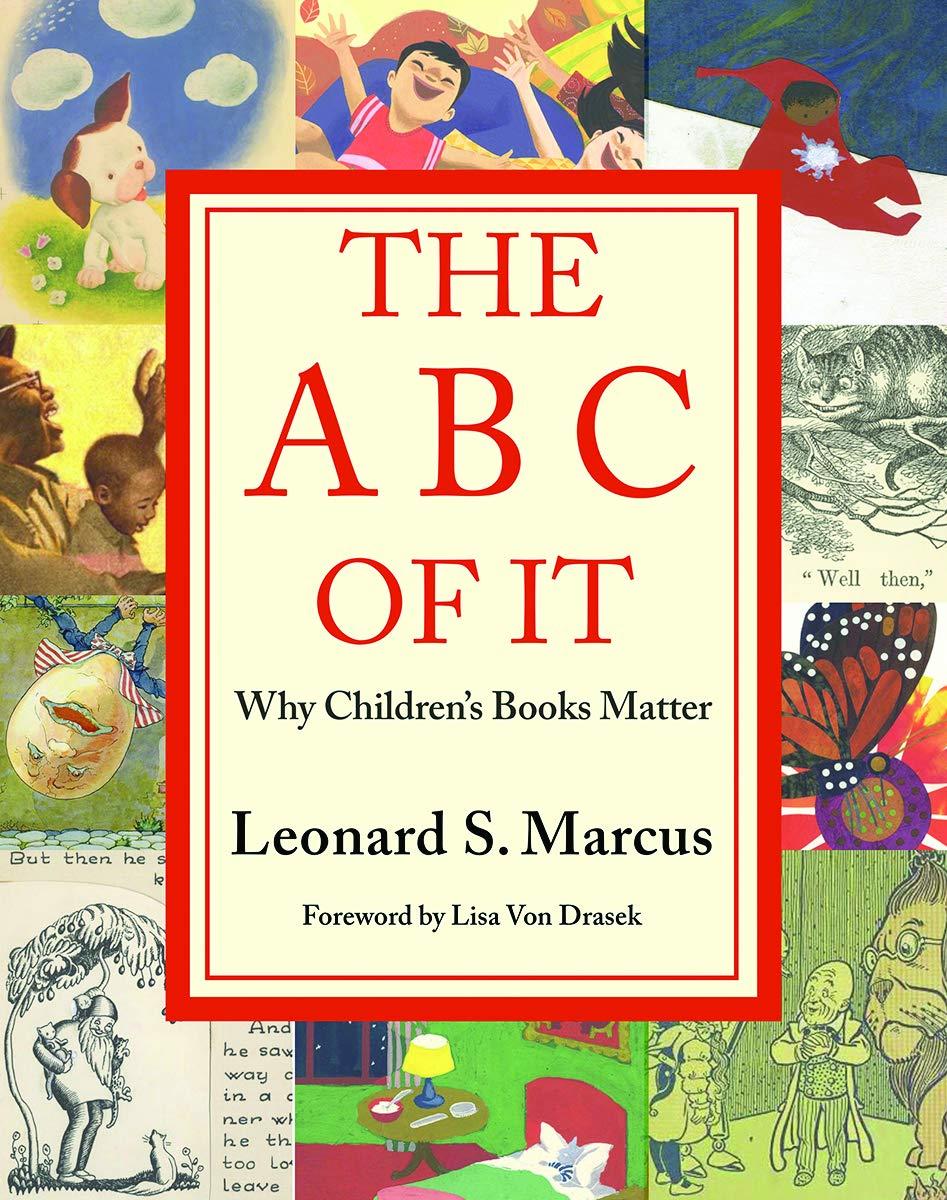

A Critical Review of THE ABC OF IT: WHY CHILDREN'S BOOKS MATTER by Leonard Marcus

On Monday, March 4, 2019, I started a twitter thread as I read through The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter by Leonard Marcus. It is the companion book (also called a catalog) for the exhibit of that name that was in New York City, and is now in Minneapolis at the University of Minnesota's Elmer L. Anderson Library. It was put together from the children's literature research collections curated by Lisa Von Drasek, but especially from the Kerlan Collection, which is, according to the website, "one of the world's greatest children's literature archives."

I did two more twitter threads on Tuesday, March 5th, and used Spooler, to combine them into this post. I've done some minor edits to fix typos.

Monday, March 4, 2019

My copy of The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter by Leonard Marcus, arrived yesterday. I bought it because of the exhibit currently at the Elmer L. Anderson Library in Minnesota and concerns that the exhibit is lacking in context.

Couldn't he insert something in his description about Native peoples? or slavery?

Without that, he is giving readers of the catalog (and if the actual exhibit is similar to the book) his version of the All White World of Children's Books.

If you see the exhibit at the Elmer L. Anderson Library, what do you notice about its POV? Its whiteness? I welcome your observations.

From what I see so far there seems to be a choice about what knowledge the exhibit disseminates.

A new section starts on p. 60: "In Nature's Classroom: The Romantic Child." On p. 67 is Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are. (Image below is from my blog post about the image and book.)

I was paging through The ABC of It and noticed the Wizard of Oz pages in the "Art of the Picture Book" section of Marcus's book.

I did two more twitter threads on Tuesday, March 5th, and used Spooler, to combine them into this post. I've done some minor edits to fix typos.

Update, April 9, 2019: I am inserting a few photographs I took of the catalog and making small revisions so that my critique flows a bit better here than it did on Twitter. I'm also changing the style I used on Twitter for book titles (cap letters) to italics.

Monday, March 4, 2019

My copy of The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter by Leonard Marcus, arrived yesterday. I bought it because of the exhibit currently at the Elmer L. Anderson Library in Minnesota and concerns that the exhibit is lacking in context.

By that, I mean that the exhibit itself seems to be avoiding critical conversations about racism of some authors, like Dr. Seuss.

Sometimes, people object to critiques (like mine) that point out omissions. Their idea is that you should review what you have in front of you (in the book) rather than what you wish was there. I don't know what theoretical framework that idea comes from, but...

...I think that idea protects the status quo. It helps everybody avoid things that make them uncomfortable... that remind them of racism, for example.

Or facts like this one: You can call Europeans who came to what is currently known as the Americas "explorers" but from a Native point of view, they were invaders.

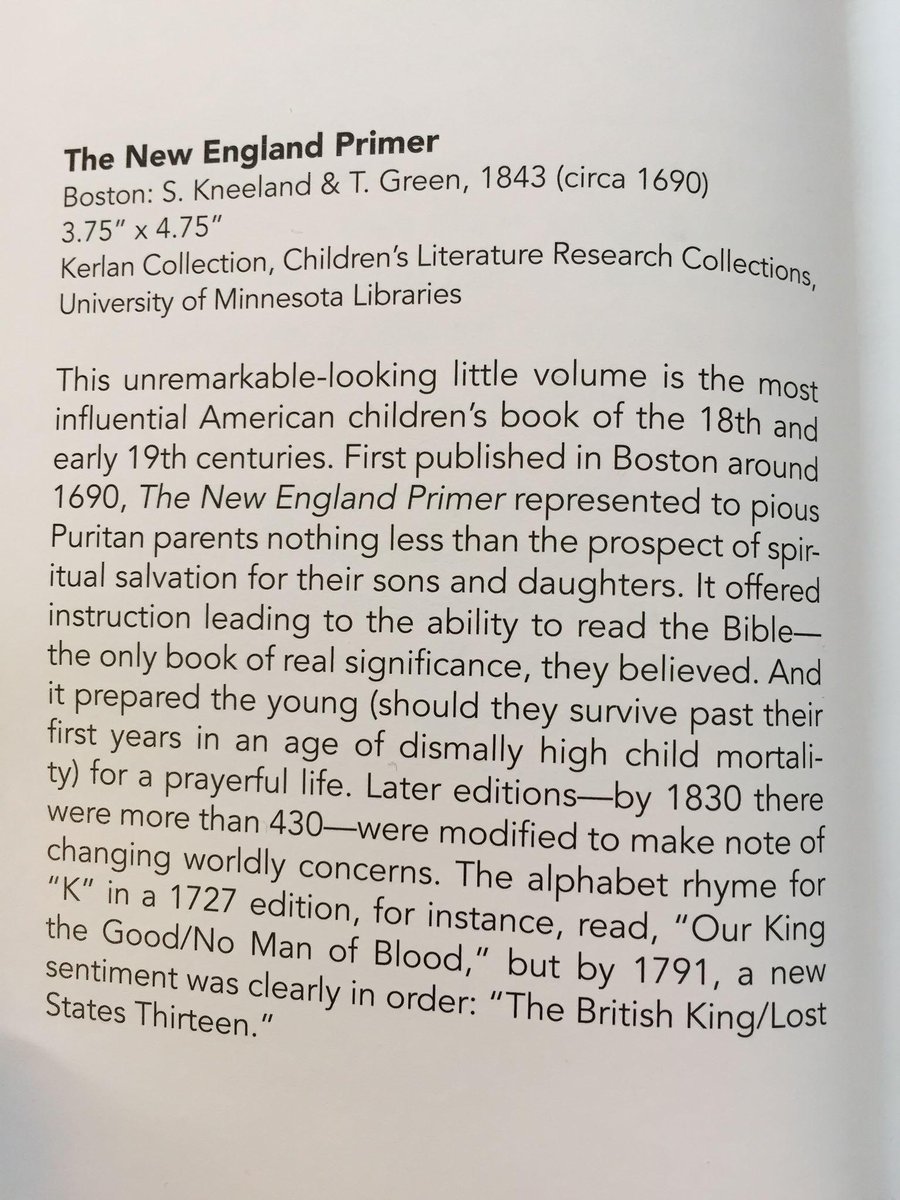

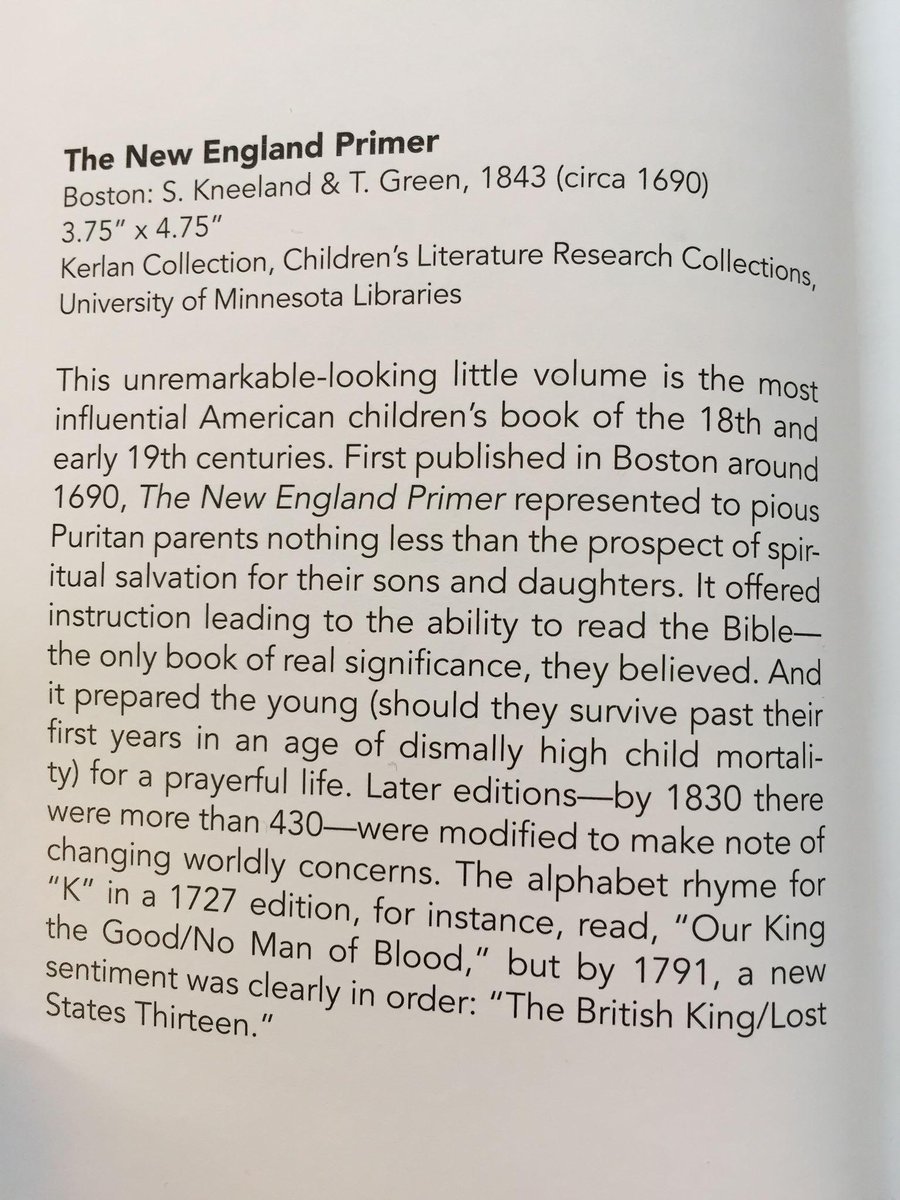

"Visions of Childhood" is the first section of The ABC of It. Its first subsection is "Sinful or Pure? The Spiritual Child." It begins with the Puritans. Cotton Mather. The book: The New England Primer. Obviously, I can't fault Marcus for what the Puritans left out of that book.

But it is fair, I think, to ask for more than what he offers in his description of the book (see below). What would it feel like, for example, if he included something about the Native Nations and people whose lands the Puritans were invading?

In the last sentences (of the description), Marcus noted that later editions were changed "to make note of changing worldly concerns." He notes, specifically, changes to the "K" rhyme:

1727 edition: "Our King the Good/No Man of Blood"

1791 edition: "The British King/Lost States Thirteen."Marcus is able to address specific "changing worldly concerns." He notes revisions that actually got done from the 1727 to the 1791 editions.

Couldn't he insert something in his description about Native peoples? or slavery?

Without that, he is giving readers of the catalog (and if the actual exhibit is similar to the book) his version of the All White World of Children's Books.

Have you been to the exhibit at the Anderson library? Does it have the New England Primer on display? The "sinful or pure" section includes William Blake's Songs of Innocence on the next two pages.

Next is "A Blank Slate: The Rational Child." Marcus begins by writing about Orbis Pictus by Comenius and Some Thoughts Concerning Education by John Locke.

Next is "A Blank Slate: The Rational Child." Marcus begins by writing about Orbis Pictus by Comenius and Some Thoughts Concerning Education by John Locke.

Those of you in children's lit know that, in 1989, the National Council of Teachers of English established the Orbis Pictus Award to honor Comenius's book. You can see Orbis Pictus, online.

Marcus's book, The ABC of It, has two photos of interior pages of Comenius's book. Each takes up half a page. One is the title page and image of Comenius; the other is "Fruits of Trees." The description for the two pages is:

"Although spiritual matters received due attention in Comenius's "pictured world," his most famous book gave pride of place to worldly matters--geography, weather, place [...] among others."

I wish the pages about spiritual matters received attention by Marcus! It would have let readers/exhibit visitors see Comenius's point of view of those spiritual matters. Go here to see. He wrote: "Indians, even to this day, worship the Devil."

Including that page would have made for some really interesting conversations there at the exhibit. Lest you try to wave Comenius's words away as a "product of his time," missionaries are still at work, today.

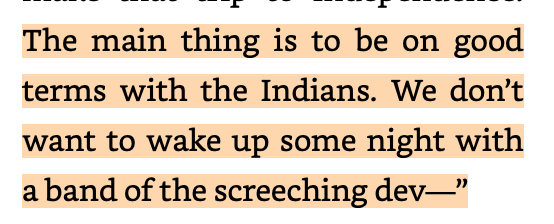

And, children's books that are read today--like Little House on the Prairie--have characters with that point of view, too. Here's Pa (who so many people think is the good guy, sympathetic to Native ppl):

|

| Excerpt from Little House on the Prairie |

One thing that many of us (scholars) ask is "who edited this book" because we think editors should catch problems (in this case, an editor with an eye towards whitewashing and racism might have asked Marcus to provide a more critical description of some of these books). I'm wondering that as I page through Marcus's The ABC of It. Who was his editor?

The next subsection is "From Rote to Rhyme." In it, there are 4 illustrations of McGuffey's Reader. Here's the first double-paged spread, with three of the illustrations on the right side:

The next subsection is "From Rote to Rhyme." In it, there are 4 illustrations of McGuffey's Reader. Here's the first double-paged spread, with three of the illustrations on the right side:

And here's the second double-paged spread:

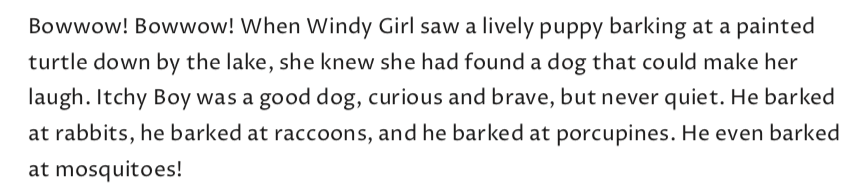

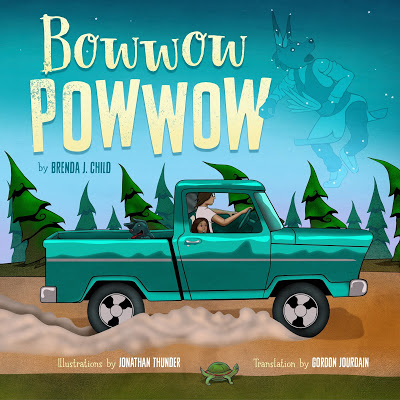

As you can see, on the left is a full page image of one page from inside a McGuffey reader. Facing it is a page with the cover of the Indian readers by Ann Nolan Clark (Singing Sioux Cowboy; see "To Remain an Indian" for a Native POV on the readers), and the covers for Bowwow Powwow and the English and Ojibwe covers for When the White Foxes Came. Marcus includes a description of the Clark book (here's an enlarged copy of the description beneath the cover of Singing Sioux Cowboy):

See? He describes the white-authored book, but includes nothing other than the citation information for the Native-authored books on that page.

As you can see, on the left is a full page image of one page from inside a McGuffey reader. Facing it is a page with the cover of the Indian readers by Ann Nolan Clark (Singing Sioux Cowboy; see "To Remain an Indian" for a Native POV on the readers), and the covers for Bowwow Powwow and the English and Ojibwe covers for When the White Foxes Came. Marcus includes a description of the Clark book (here's an enlarged copy of the description beneath the cover of Singing Sioux Cowboy):

See? He describes the white-authored book, but includes nothing other than the citation information for the Native-authored books on that page.

Those three covers are books by Native writers. I have lot of questions. Why are they in this "From Rote to Rhyme" section? Here's the opening paragraph for Brenda Child's Bowwow Powwow:

See? There's no rhyme there. Did Marcus read the book? Did he make a judgement about the contents about the book because the title rhymes?

Bowwow Powwow is excellent, by the way, and if I was doing that ABC book, I'd have cut some of the McGuffy pages so it could have more space.

The other Native-authored book on that page is When the White Foxes Came. I don't know that bk, but I do know some of the people (Margaret Noodin and Mary Hermes) who put it together. Marcus included the English and Ojibwe covers, which is good but I'd rather see less of McGuffey and more of Native writers.

Next in that section is page 28, about Theodor Geisel (Dr Seuss). There's a photo of him and the covers of The Cat in the Hat and The Cat in the Hat Comes Back. Those bks rhyme, so it makes sense that they'd be in this section of Rote and Rhyme. But, in the accompanying text, there is no mention of Seuss's racist cartoons.

Seuss is in the news a lot of late because of this article: The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books. If you listen to NPR you heard abt it. If you read People (the news and entertainment magazine), you saw it there.

If you see the exhibit at the Elmer L. Anderson Library, what do you notice about its POV? Its whiteness? I welcome your observations.

Tuesday, March 6, 2019

Starting Day 2 of my review of Leonard Marcus's The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter. I read up to page 29 yesterday.

The next subsection of "Visions of Childhood" is "The Work of Play: The Progressive Child." It begins with Lucy Sprague Mitchell's Here and Now Story Book. In my doctoral studies, I read abt her, the Bank Street school, and her ideas about what children need, in their bks.

Mitchell said that kids need "here and now" rather than fairy tales. In The ABC of It, Marcus includes the cover of Mitchell's book, the intro (which says the stories in the book are "experiments in content and form"), and "Marni Takes A Ride in A Wagon."

You can see Mitchell's Here and Now Story Book here (in original format) and here (transcribed). It was published in 1921.

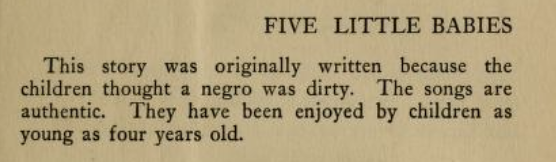

On page 290 is "Five Little Babies." It is racist, as you'll see. The intro to it says:

"This story was originally written because the children thought a negro was dirty. The songs are authentic. They have been enjoyed by children as young as four years old."

|

| Screen cap of Five Little Babies |

In his description of Mitchell's book, Marcus doesn't mention its racist contents. Yesterday's thread on his bk, The ABC of It, is meant to ask questions about what gets put into books about children's books--and what is left out.

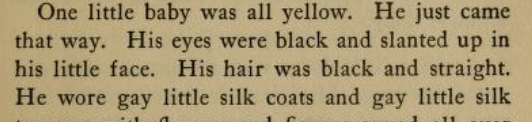

In the Five Little Babies (that Marcus didn't include), there's a "yellow" baby "in China", a "brown" baby "in India," a "black" baby "in Africa" and a "red baby" who was an "Indian baby" who lived "long, long ago" in America... And of course, a "white" baby that is "in your own country every day and he is a little American baby."

|

| Screen cap of Five Little Babies |

The physical descriptions for the babies are racist. "Slanted" eyes, "kinky" hair and wearing "a loincloth" or nothing at all.

American babies have white skin, blue eyes, and gold hair.

Mitchell wrote Native ppl out of existence, and placed all others, elsewhere on the globe (not in the U.S.).

American babies have white skin, blue eyes, and gold hair.

Mitchell wrote Native ppl out of existence, and placed all others, elsewhere on the globe (not in the U.S.).

You know that Native people exist, today, right? Surely Mitchell knew that, too.

And you know that in 1921, the US wasn't populated exclusively by people with white skin, blue eyes and gold hair. Surely, Mitchell knew that as well.

So, how do we explain Mitchell's "Five Babies"?! And why did Marcus choose not to refer to that story in Mitchell's book?

And you know that in 1921, the US wasn't populated exclusively by people with white skin, blue eyes and gold hair. Surely, Mitchell knew that as well.

So, how do we explain Mitchell's "Five Babies"?! And why did Marcus choose not to refer to that story in Mitchell's book?

These are the kinds of questions that an exhibit at an institution like University of Minnesota's Elmer L. Anderson library ought to engage with, in some way.

In January, Lisa Von Drasek (the curator) gave an interview to Betsy Bird at Fuse 8 (Bird's blog at School Library Journal) about the exhibit. In the interview, Von Drasek said

In January, Lisa Von Drasek (the curator) gave an interview to Betsy Bird at Fuse 8 (Bird's blog at School Library Journal) about the exhibit. In the interview, Von Drasek said

"U of M is a land grant university. This is important because our mission is to research, create, and disseminate knowledge."

From what I see so far there seems to be a choice about what knowledge the exhibit disseminates.

It seems like The ABC of It -- the physical exhibit and the book (catalog) of it -- are in that "warm fuzzy" space that is very white and best characterized as nostalgia.

Why did Marcus avoid telling us that Geisel did racist work? And that Mitchell created racist stories?

Why did Marcus avoid telling us that Geisel did racist work? And that Mitchell created racist stories?

Obviously, THAT is not the point of the exhibit.

So, what IS the point?

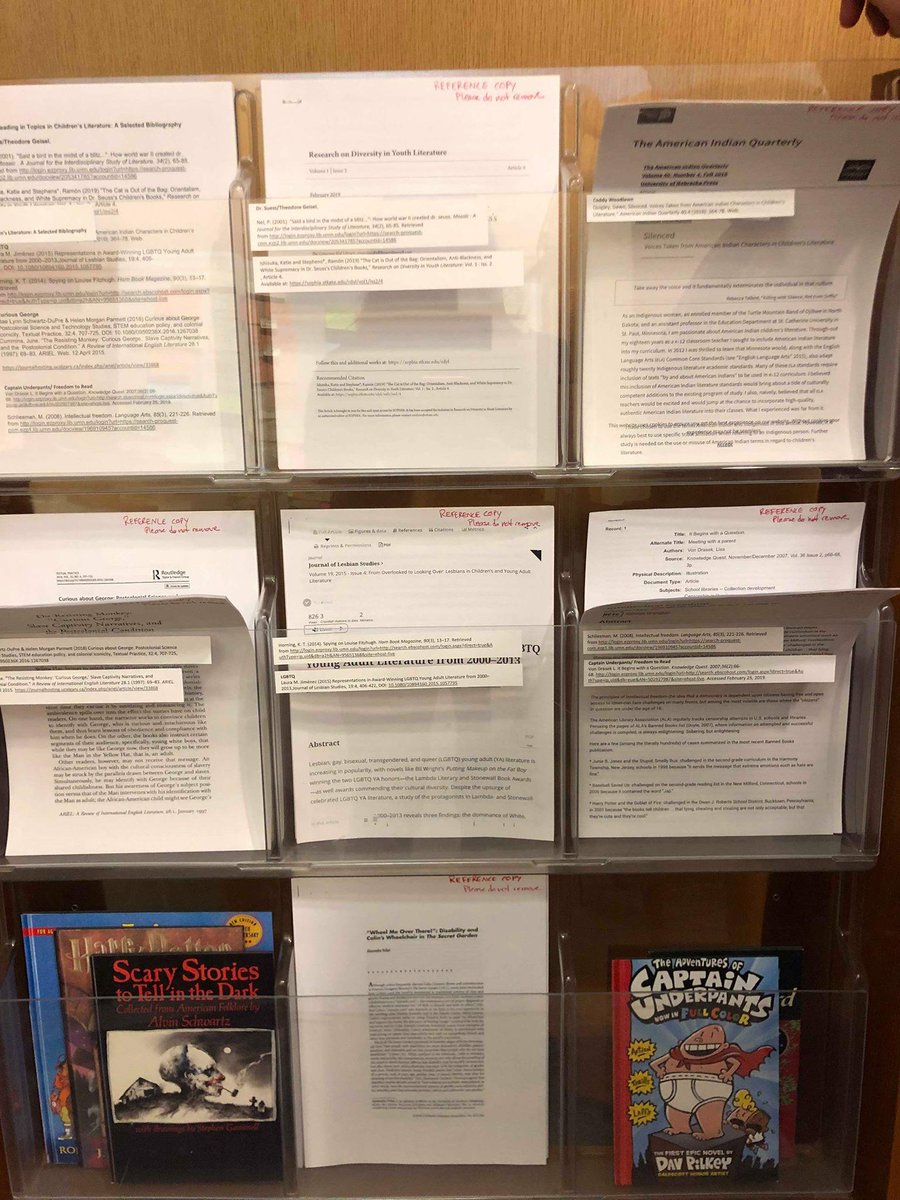

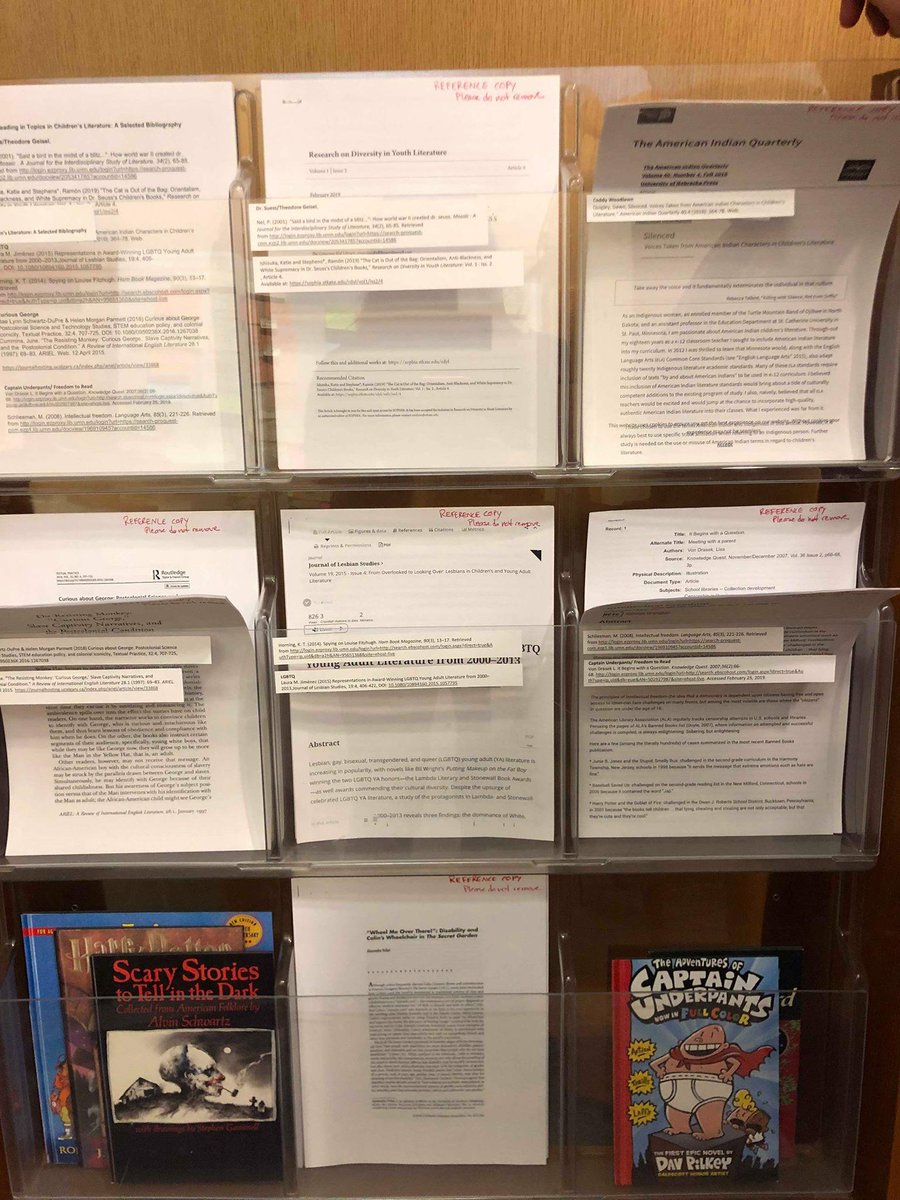

The exhibit opened on February 27th. Over in a corner, there is a rack of articles that has a copy of the Seuss article by Ishizuka and Stephens, "The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books" but...

So, what IS the point?

The exhibit opened on February 27th. Over in a corner, there is a rack of articles that has a copy of the Seuss article by Ishizuka and Stephens, "The Cat is Out of the Bag: Orientalism, Anti-Blackness, and White Supremacy in Dr. Seuss's Children's Books" but...

... why can't excerpts from the article be part of the exhibit that has the Seuss books?

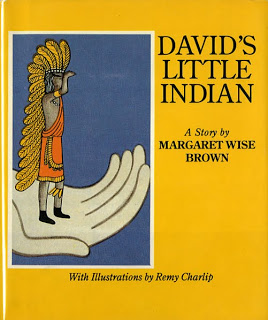

Marcus tells us that Margaret Wise Brown was Mitchell's "literary protégée" (p. 30). On page 33, he gives us covers of three of her books (The Noisy Book; The Seashore Noisy Book; The Indoor Noisy Book). Pages 34-37 (four entire double-paged spreads) are devoted to Goodnight Moon. He could have shown us one of her racist books (David's Little Indian) but he didn't.

Marcus writes that Maurice Sendak put Mitchell's ideas to work in his books. On page 38, he includes Ruth Krauss books that Sendak illustrated. Sendak is a towering figure in kidlit. But he also did lot of stereotypical Indians AND...

What was he doing with a feather on his head?! Go here for details.

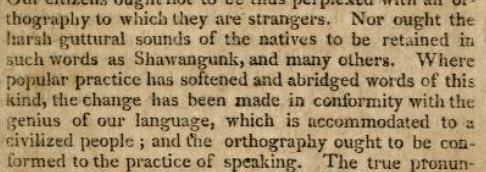

Next up in "Visions of Childhood" is "Building Citizens: The Patriotic Child." It starts w/ Noah Webster's The American Spelling Book. Marcus writes that Webster "yearned for an American English purged of what he believed to be the excesses of British aristocratic influence."

On p. 42 are the cover and two interior pages from The American Spelling Book and a print of Webster titled "The Schoolmaster of the Republic." So... what did that schoolmaster have to say about Native words?

Webster didn't want British influence, and he didn't want "guttural sounds of the Natives" either. Marcus felt it important to note that Webster didn't want British influence but Marcus chose to ignore what Webster said about Native language.

|

| "gutteral sounds of the Natives" screen cap from Webster's spelling book. |

On page 45, Marcus has Ann Nolan Clark's In My Mother's House. Its illustrations are by Velino Herrera of Zia Pueblo (published in 1941). Marcus writes that Clark worked for the Bureau of Indian Affairs and that her bks played a key role in the US governments "new, more culturally respectful approach to the education of Native American children." There are several of these books, most written by Clark and with illustrations by Native artists. (See "To Remain an Indian" for some discussion of the books.)

I'm glad to see that Marcus included In My Mother's House but wonder what it looks like in the physical exhibit. Do people who see it know what preceded this more "respectful approach"? Do they know about the 'kill the Indian and save the man' philosophy of the US government schools for Native kids?

I hope #DiversityJedi see the exhibit (or the book/catalog about it) and offer critiques of content for which they have expertise. There's a lot I don't know anything about. On page 48-49, for example, Marcus shows comic books published in Mumbai.

On page 52 is a new subsection, "Down the Rabbit Hole," which is about Alice in Wonderland. Marcus gives eight pages to it.

Update on Thursday, March 7th: A colleague wrote to tell me that the Amar Chitra Katha stories that Marcus has in his book on page 48 and 49 are racist. She recommends an article in The Atlantic by Shaan Amin: The Dark Side of the Comics that Redefined Hinduism, published on December 30, 2017. About the series, Marcus's description says that these comics "introduced tens of millions of English-speaking predominantly middle-class Indian youngsters to their religious and cultural roots."

On page 52 is a new subsection, "Down the Rabbit Hole," which is about Alice in Wonderland. Marcus gives eight pages to it.

A new section starts on p. 60: "In Nature's Classroom: The Romantic Child." On p. 67 is Sendak's Where the Wild Things Are. (Image below is from my blog post about the image and book.)

Pages 68-69 are about E.B. White. About Charlotte's Web, Marcus writes: "In the atomic age, he [White] recognized, the earth was perishable and in need of protection. What could save it? Wise leaders like Charlotte, or a world forum like this story's barnyard, where even a rat may realize the sense of keeping the web intact."

E.B. White did some stereotyping of Native people in Stuart Little and in Trumpet of the Swan (are you getting a good sense of how many esteemed and famous writers/people in children's literature held/hold stereotypical views?!):

|

| Excerpt from Trumpet of the Swan |

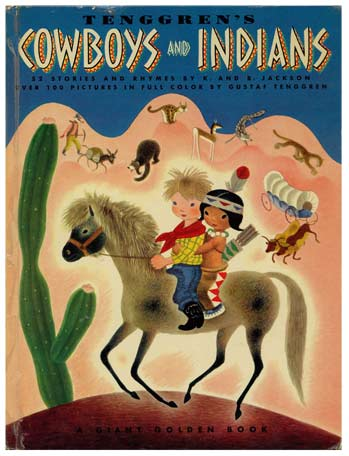

The remaining pages in this section are about Hans Christian Andersen and Gustaf Tenggren. Several years ago, Marcus did a book about the Little Golden Books, so he probably saw Tenggren's Cowboys and Indians, but he chose not to include it in The ABC of It.

It may be that Cowboys and Indians isn't in The ABC of It because that art is not in the Kerlan. Marcus could have noted it, somewhere in the book. And, it could be noted in the physical exhibit.

Tuesday, March 7 -- late afternoon

Day 2-late afternoon thread on The ABC of It: Why Children's Books Matter, a physical exhibit (and companion book/catalog) at the Anderson Library at the University of Minnesota.

I did a thread yesterday and one this morning and am doing this one because tomorrow (Wed) night, Shannon Gibney is on a panel, there, about the exhibit.

Shannon does some terrific work on issues of representation and misrepresentation. One of her areas of interest/expertise is about Native peoples.

I was paging through The ABC of It and noticed the Wizard of Oz pages in the "Art of the Picture Book" section of Marcus's book.

There are two pages on The Wizard of Oz.

The accompanying text notes that L. Frank Baum had been an actor, a farmer, and ... a newspaper editor. Marcus knows that Baum was a newspaper editor. I am going to assume he knows about the newspaper editorials that Baum wrote.

The accompanying text notes that L. Frank Baum had been an actor, a farmer, and ... a newspaper editor. Marcus knows that Baum was a newspaper editor. I am going to assume he knows about the newspaper editorials that Baum wrote.

He doesn't mention the contents of Baum's editorials, but I think he should have. You may know about them if you listened to this NPR story in 2010. In one of his editorials, Baum called for "the total annihilation of the few remaining Indians."

Marcus and Lisa Von Drasek could have created a way for visitors to "speak back" to that editorial--if they had included it.

These aren't abstract or academic concerns. Native people know about Baum's editorials. We don't have a warm fuzzy for Oz.

These aren't abstract or academic concerns. Native people know about Baum's editorials. We don't have a warm fuzzy for Oz.

Native people who come to the exhibit will see Baum, glorified.

In many places (books/articles/online), there are conversations that tell ppl to keep the art and the artist separate. That's handy for some. It doesn't work for me, and it doesn't work for others, either.

In many places (books/articles/online), there are conversations that tell ppl to keep the art and the artist separate. That's handy for some. It doesn't work for me, and it doesn't work for others, either.

In her 2018 novel, Hearts Unbroken, Muscogee Creek writer Cynthia Leitich Smith takes up that "separate the art from the artist" idea. Her book is set in a high school that is doing an Oz play. Lou (the main character) and Hughie (Lou's brother) are citizens of the Muscogee Nation.

Their mom is in law school and is especially interested in protecting the rights of Native children via the Indian Child Welfare Act.

Their mom knows about the Baum editorials.

Their mom knows about the Baum editorials.

When Hughie (Lou's brother) learns about them, he has a hard time deciding what to do. Go ahead and do the play? What is the cost to him, emotionally, if he goes ahead?

Smith lays all that out in her book.

Smith lays all that out in her book.

The ABC of It book/catalog for the exhibit avoids Baum's editorials. It looks the other way. The exhibit is in Minnesota. It looks away from racism, on land that once belonged to Native people.

There are eleven tribal nations located in Minnesota.

There is an American Indian Studies department at the University of Minnesota.

What does this exhibit's treatment of Oz/Baum tell the faculty, their students, their children?

There is an American Indian Studies department at the University of Minnesota.

What does this exhibit's treatment of Oz/Baum tell the faculty, their students, their children?

****

I may continue my review of The ABC Of It but wanted to bring what I've done so far on Twitter, here, because AICL is where I publish most of my writing.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)