Several months ago, we received a copy of Brittany Luby and Michaela Goade's

Encounter. It came out in October of 2019 from one of the Big Five publishers: Little, Brown Books for Young Readers. Books published by the Big Five receive visibility that books from smaller publishers do not. It is exceedingly difficult for Native writers to get in those Big Five doors. We had long conversations about

Encounter because of that, and because the author and illustrator are Native. Regular readers of AICL know that we are strong advocates for #OwnVoices.

In the end, we decided we cannot recommend it.

We hope to share our conversations about

Encounter with AICL's readers but for now, we are giving you a short version of our thoughts on the book. The publisher's description of the book is below, followed by our respective thoughts on the book.

A powerful imagining by two Native creators of a first encounter between two very different people that celebrates our ability to acknowledge difference and find common ground.

Based on the real journal kept by French explorer Jacques Cartier in 1534, Encounter imagines a first meeting between a French sailor and a Stadaconan fisher. As they navigate their differences, the wise animals around them note their similarities, illuminating common ground.

This extraordinary imagining by Brittany Luby, Professor of Indigenous History, is paired with stunning art by Michaela Goade, winner of 2018 American Indian Youth Literature Best Picture Book Award. Encounter is a luminous telling from two Indigenous creators that invites readers to reckon with the past, and to welcome, together, a future that is yet unchartered.

****

Debbie's thoughts:

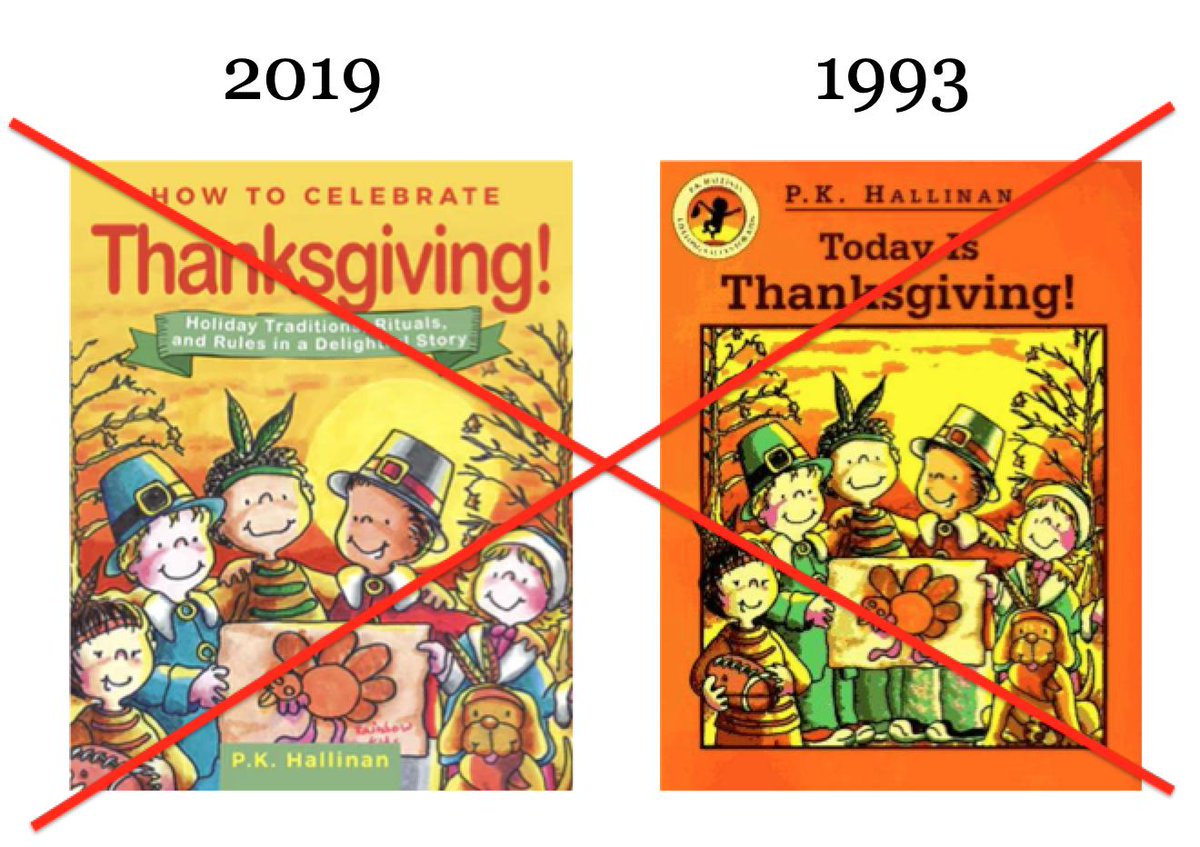

When I first learned of the book, my thoughts turned to Thanksgiving picture books that show Pilgrims and Indians (sometimes Wampanoags) meeting each other. In particular, Rockwell's

Thanksgiving Day came to mind. In it, the children are doing a reenactment of the Pilgrim's landing. One child playing the part of a Pilgrim is thankful that the Pilgrims were "greeted kindly by the Wampanoag people who shared their land with them." Another child, playing the part of a Wampanoag, is thankful that the Pilgrims are peaceful. Another, playing the part of a Wampanoag leader, talked about how the Wampanoag and Pilgrim people shared a feast that autumn day. It is, in tone, idyllic.

Rockwell's book came out in 1999 but ones like it come out every year. Writers and illustrators, it seems to me, keep trying to tell that same story. Each year there is pushback to that story. On social media, people replied to tweets and posts from teachers who showed their classes of children, reenacting that "first Thanksgiving." It seems people in the US are determined to turn that idyllic story into the truth. And so--when I first saw

Encounter--I was afraid that it would be celebrated for its storyline, and because of its author and illustrator. Over time, my fears were realized. It got starred reviews, was featured on NPR, and it is now appearing on Best of 2019 book lists.

It definitely appeals to White readers, but I could not--and cannot--imagine handing the book to a Native child or Native family. I'm glad for the visibility that it brings to both, Luby and Goade, and I hope that it leads to more opportunities with a major publisher. I don't think any library or home needs imagined stories like this one. I think we need ones that are honest tellings of history.

****

Jean's thoughts:

The Author's Reflection and the Historical Note in the back of the book help explain what Brittany Luby is going for with Encounter: an intentional contrast with actual events, a thought-provoking counter-story. So I gave a lot of attention to how it felt to read and re-read the story and the author's comments, in light of all that still sits with me after Debbie and I adapted

An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States for Young People. What would it mean to kids -- Native kids and non-Native -- that this story about an imaginary innocent Native/white friendship is so far from what really happened?

Reading

Encounter at this point in life turned out to be work. I'm white; my husband and our kids are Mvskoke Creek. I'm also of a generation that pretty much drowned in "cowboys/cavalry & Indians" imagery, and I had just spent several years immersed in Indigenous history. I found that I did a lot of mental and emotional processing about

Encounter. No need to go into all that, but it made me see that sharing it with kids would be complicated. Before long, we could tell the book was getting popular, and would inevitably be shared with lots of children, probably plucked off bookshelves for friendship-affirming read-alouds.

Debbie mentioned (above) those persistent Thanksgiving myths. "First contacts" between Europeans and Indigenous peoples are also heavily mythologized as part of the grand American narrative. That's what schooling tells us about US history, over decades of our lives, and it's hard to un-do. Some people don't want to undo it. (Many Native families provide the less shiny reality for their children, though.)

So how are professionals and parents (especially non-Natives) supposed to help children engage with a fantasy about "first contact" if they aren't clear on the reality, themselves? You can't expect non-Native children to grasp the import of a story like

Encounter before they comprehend the reality. And if you present the fantasy in

Encounter to Native children without showing that you know and believe the real history, and without making sure their classmates also get it, they will see the lie. They would feel -- as Debbie said in one of our talks about it -- betrayed.

We know, given the make-up of the school and library professions, it'll be mostly non-Native professionals who read or recommend

Encounter to their students or patrons. So for a while my head was full of caveats. The adults would need to be deeply intentional & thoroughly prepared, and give serious thought to their goals for sharing the book. There were things to be aware of, groundwork to lay, things to do and not do. Calling into question the entire settler-colonizer mindset... Someone had suggested on Twitter that adults could read the Author Reflection and Historical Note to children first. But it seemed to me that the author's comments alone couldn't fill the gaps in many peoples' (mis)understanding of Indigenous history.

And here's the problem: How many teachers or librarians are able (or willing) to do that much work in order to share a specific picture book? Isn't it more likely to be shared as a sweet story of how people ought to treat each other?

During one conversation, after giving solid attention to my tangled thoughts, Debbie asked, "Would you read it to Jack?" (Jack's my 9-year-old grandson.) My brain started to say, "Mmmaybe, but only if --" But my heart said, "No. No, I wouldn't."

I've applied that question to critiques of many other books -- "What would it feel like to be one or another of my grandkids, reading this?" Why it wasn't with me from the beginning on this one is puzzling.

For non-Native (especially White) adults, there may be some value in personally, privately using counter-narratives like this one, with oneself, to face the chasm between respectful human relationships that sustain life and the real Indigenous history of the continent currently known as North America. But it doesn't feel like a book for children.

****

Debbie and Jean's thoughts:

We want to see books by Native writers and illustrators succeed. Our commitment to them, however, is superceded by our commitment to children. We'd like to think that a book like this has an audience, but at this point, we're not sure who that would audience would be.

As noted above, we hope that the book brings visibility to Luby and Goade, and we look forward to seeing more from them in the future.

Red River Resistance is the second graphic novel in Katherena Vermette's A Girl Called Echo series. The Metis teen protagonist of Volume 1 (Pemmican Wars) is still quiet, still spends a lot of time with earbuds in, listening to her music, but she's becoming less isolated. She is befriended by a classmate named Micah. She gets involved with the school's Indigenous Student Leadership group, under the guidance of teachers Mr. Bee and Mx Francois. She plays in the snow with her foster family. And she smiles a bit. But powerful dreams and daydreams still take her into the Metis history of what is currently called Canada. This time, her dream episodes are set in 1869-70, when political machinations in Canada focused on pushing Indigenous and Metis people further and further west. Metis leader Louis Riel is a central figure in the dream events Echo experiences.

Red River Resistance is the second graphic novel in Katherena Vermette's A Girl Called Echo series. The Metis teen protagonist of Volume 1 (Pemmican Wars) is still quiet, still spends a lot of time with earbuds in, listening to her music, but she's becoming less isolated. She is befriended by a classmate named Micah. She gets involved with the school's Indigenous Student Leadership group, under the guidance of teachers Mr. Bee and Mx Francois. She plays in the snow with her foster family. And she smiles a bit. But powerful dreams and daydreams still take her into the Metis history of what is currently called Canada. This time, her dream episodes are set in 1869-70, when political machinations in Canada focused on pushing Indigenous and Metis people further and further west. Metis leader Louis Riel is a central figure in the dream events Echo experiences.