Update: April 17, 2018

Last night (April 16, 2018),

Jace Weaver, the director of the Institute of Native American Studies at the University of Georgia, posted a comment about John Sedgwick's

Blood Moon to

his Facebook page. With his permission, I am quoting parts of it.

Dr. Weaver began with this word: "Warning." He then said that the publisher, Simon and Schuster, had asked him and

Colin Calloway (a professor of history and Native American Studies at Dartmouth) to vet

Blood Moon. It was already typeset in galleys, and, Dr. Weaver said, "it was horrible." It had "numerous factual errors" and "faulty interpretations." It bought into and trafficked in "the worst stereotypes." Both professors provided detailed readers' reports, but Sedgwick (the author) did not correct all the factual errors, and he "did nothing about tone or stereotypes."

Dr. Weaver's post ends with this:

"The worst of it is, we're thanked as 'two of the most authoritative contemporary scholars of Native Americans.' Arg! Avoid this book!"

Here's a screen cap from the book:

See that? Sedgwick writes that he owes Weaver and Calloway "great debts." I think he owes them an apology. And that last line "I take full responsibility for any mistakes that remain" is Sedgwick's shield. It is a disclaimer that tells us,

without telling us, that he ignored some of their input. His use of "mistakes" is also worth thinking about. Factual errors are one thing but the tone that Weaver objected to? That sort of thing can be put forth as point of view. What Weaver and Calloway (and me, below) say is derogatory stereotyping, Sedgwick can say he sees it differently. Someone once told me that what I call a negative stereotype can be seen by someone else as a heroic image.

Based on what Weaver said in his Facebook post and what I saw of the book, John Sedgwick's Blood Moon: An American Epic of War and Splendor in the Cherokee Nation is definitely in the Not Recommended category.

Because of Simon and Schuster's marketing budget, it is going to be crucial that we use word-of-mouth to let others know there are problems in this book. It should not be used in high school classrooms.

____________

Below is my original post, published on April 12, 2018.

A reader wrote to ask if I've read John Sedgwick's

Blood Moon: An American Epic of War and Splendor in the Cherokee Nation. It isn't for children or young adults, but, the reader notes, some people might get it for a young adult or a young adult collection in a library.

I haven't read it. I can make some initial observations, based on how I go about analyzing books. I'm using what I see in the preview from Google Books for some of these observations and I'm using information made available about the book, including the

book trailer at the Simon and Schuster website. Let's start with that video.

Sedgwick begins with "who knew" in an astonished tone, that Native people fought in the Civil War. Whenever someone uses that "who knew?" phrase that way, we are told a lot about that person. In this case, Sedgwick means that he didn't know, and that people he knows didn't know. From that body of people who did not know, he utters the "who knew" phrase. You know who knew? Cherokees. They know. So do a lot of Native people, including those of us who read beyond the master narratives of history. Then, he talks about how people know about the Trail of Tears, but that they don't know about a disagreement within the Cherokee Nation, about removal. That's what his book is about.

Now, the book itself:

First: Is Sedgwick (the author) Cherokee? Answer: No. Does that mean he cannot write this book? Obviously, no. The book is out there, from a major publisher. Does it mean he should not write the book? Again, no. Anyone can write about anything they want to. The significant questions are these: are the contents of the book accurate? Who vetted the book? When/if I get the book, will I find that Sedgwick worked with the Cherokee Nation on this book? Was their feedback used? If their feedback was ignored (that happens in children's lit, for sure), it sure would be good to know, but, that sort of feedback isn't usually provided. Sometimes, it comes out, post-publication.

Second: What is Sedgwick's source for what he says about a blood moon? In his "A Note on the Title" page, he writes this:

A blood moon is a rare form of lunar eclipse. For the Cherokee, any vanishing from the night sky was troubling, as it threw their cosmos out of order. A blood moon was especially terrifying, since the moon did not disappear, but turned bloodred. Meteorologists now see that a blood moon is actually lit by an unusual sunset glow picked up from the earth's atmosphere as the sunlight brushes past. But the Cherokee considered the sight an ill portent. The moon was red with rage over what lay below.

Some will find that note compelling. Obviously, Sedgwick is taken with it. He used it as the title and framework for his book. If I was doing an in-depth analysis, I'd try to find out what his source is. Is there a source for it in the back matter of the book? Maybe. If there is, I'd verify that source, too. There's a whole of of "knowledge" out there that gets put forth as being from this or that unnamed Native person that is actually some of the White Man's Indian imaginings. The note is also one that puts one peoples ways of viewing the world into a framework that casts them as simple, primitive, superstitious, etc. Opposite of them are meteorologists. Science. There's a whole lot of denigration and misrepresentation going on in that sort of binary!

Third: What is Sedgwick's orientation to Indigenous peoples? The introduction gives us a lot of insight to it. He writes:

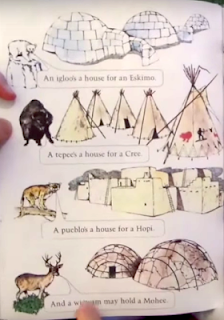

While the Indians were skilled as scouts, trackers, horsemen, and sharpshooters, their greatest value may have been their fighting skills. Shaped by a warrior culture, most were used to violence, and they took to battle. Their long black hair spilling out from under their caps, their shoddy uniforms ill-fitting, their faces painted in harsh war colors, they surged into battle with a terrifying cry, equipped not just with army-issue rifles but also with hunting knives, tomahawks, and often, bows and arrows. Even when mounted on horses, they exhibited a deadly aim, and their arrows sank deep, leaving their victims as much astonished as agonized. They'd close fast, whip out a tomahawk to dispatch their man, then pounce on the corpse with a bowie knife to shear off a scalp to lift to the sky in triumph.

Sedgwick says they were "shaped by a warrior culture." I think Sedgwick's thinking is shaped by that master narrative and its stereotypes. Shall we count them?

- warriors

- long black hair

- face paint

- terrifying (war) cry

- knives, tomahawks, bows and arrows

- scalping

A few pages later, I see "Great Spirit" and another problematic binary (would they "run to the wild" or to the "bright promise of industrial civilization").

Having read that much, I have serious doubts about this book. Sounds to me like stereotypes form the foundation of how he's writing. If I get the book and read it, I'll be back with a review. In the meantime, I welcome your thoughts.