Yesterday, Betsy Bird at School Library Journal wrote about a significant change to the picture book, Lady Bug Girl, written by David Soman and illustrated by Jacky Davis. First published in 2008, it came to my attention when a reader wrote to me about the endpapers, which showed Lady Bug Girl in a headdress. At the time, I wrote a Dear Parents of Ladybug Girl post (writing to the author and illustrator as her parents).

Looking at the image now, I'm drawn to what she's doing: she's got what looks like a lipstick in her hand and is, presumably putting "war paint" on her cheeks. See? David Arnold's character did that in Mosquitoland. Remember that? (My apologies for the poor quality of the images I'm using today.)

Well, a new edition of Lady Bug Girl is out, and, as Betsy noted, Lady Bug Girl in a headdress is gone from the endpapers. I was pleased as can be about that change! Below are the covers for the 2015 "Super Fan Edition" and beneath it is the original 2008 cover.

And here's the changed endpapers:

It is the second book I'm writing about this year, that has been changed--for the better--and as such, something all of us can celebrate! Thank you, Soman, Davis, and Dial (the publisher) for deciding to remove it. It is a step in the right direction. Betsy and I agree--if there was a note in the book about the change, it would help people take a step in the right direction with you, Soman and Davis. For now, though, thank you!

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

- Debbie on Social Media

- 2024 American Indian Literature Award Medal Acceptance Speeches

- Native Removals in 2025 by US Government

Showing posts with label revised. Show all posts

Showing posts with label revised. Show all posts

Wednesday, November 11, 2015

Ladybug Girl in Headdress? Gone!

Labels:

Ladybug Girl,

revised,

stereotypes,

war paint

Thursday, October 29, 2015

Not recommended: A FINE DESSERT by Emily Jenkins and Sophie Blackall

Scroll down to the bottom of this post to see links to discussions of A Fine Dessert, discussions I'm framing as what-to-do about books like it, and, 2016 discussions of A Birthday Cake for George Washington (another book that depicts smiling slaves) The list of books that have been revised is no longer on this page. It has its own page: "Stereotypical Words and Images: Gone!"

Eds. Note, Nov 1, 2015:

Emily Jenkins, the author of A FINE DESSERT issued an apology this morning, posting it at the Calling Caldecott page and at Reading While White. Here are her words, from Reading While White:

~~~~~~~~~~

Thursday, October 29, 2015

Some months ago, a reader asked me if I'd seen A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat written by Emily Jenkins, and illustrated by Sophie Blackall. The person who wrote to me knows of my interest in diversity and the ways that Native peoples are depicted---and omitted--in children's books. Here's the synopsis:

Published this year, A Fine Dessert arrives in the midst of national discussions of diversity. It is an excellent example of the status quo in children's literature, in which white privilege drives the creation, production, and review of children's and young adult literature.

A Fine Dessert is written and illustrated by white people.

A Fine Dessert is published by a major publisher.

A Fine Dessert, however, isn't an "all white book."

As the synopsis indicates, the author and illustrator included people who are not white. How they did that is deeply problematic. In recent days, Jenkins and Blackall have not been able to ignore the words of those who find their book outrageous. Blackall's response on Oct 23rd is excerpted below; Jenkins responded on October 28th.

The Horn Book's "Calling Caldecott" blog launched a discussion of A Fine Dessert on September 23, 2015. Robin Smith opened the discussion with an overview of the book that includes this paragraph:

Smith also wrote:

The "online talk" at that time was a blog post by Elisa Gall, a librarian who titled her blog post A Fine Dessert: Sweet Intentions, Sour Aftertaste. On August 4th, she wrote that:

On October 23rd, Sophie Blackall--the illustrator--joined the discussion at Calling Caldecott, saying she had decided to respond to the criticism of how she depicted slavery. She linked to her blog, where she wrote:

Praise is not the response from Black women and mothers.

On October 25 at 12:37, fangirlJeanne's, who identifies as a Polynesian woman of color, sent a tweet that got right to the heart of the matter. She wrote that "Authors who assume a young reader doesn't know about slavery or racism in America is writing for a white reader." In a series of tweets, she wrote about the life of children of color. With those tweets, she demonstrated that the notion of "age appropriate" content is specific to white children, who aren't amongst the demographics that experienced--and experience--bullying and bigoted attacks.

At 1:00, she shared an image of the four pages in the book that Sophie Blackall has in her blog post, saying that these illustrations make her sick and sad:

The conversation about the book grew larger. Some people went to Blackall's post and submitted comments that she subsequently deleted. The explanation for why she deleted them rang hollow. And then sometime in the last 24 hours, she added this to the original blog post:

My hope is that the people on the Caldecott committee are reading the conversations about the book and that they will subsequently choose not to name A Fine Dessert as deserving of Caldecott recognition.

The book is going to do well, regardless of the committee decision. Yesterday, the New York Times named it as one of the best illustrated books of 2015. That, too, speaks to a whiteness that must be examined.

In this post, I've focused on the depictions of slavery. I've not said anything about Native people and our absence from Jenkins and Blackall's historical narrative. Honestly, given what they did with slavery, I'm glad of that omission. I'm reminded of Taylor, a fifth grader who was learning to think critically about Thanksgiving. She wrote "Do you mean all those Thanksgiving worksheets we had to color every year with all those smiling Indians were wrong?" The American settings for A Fine Dessert, of course, are all on land that belonged to Native peoples who were forcibly removed and killed to make way for Americans to raise their families, to pursue their American dreams.

I imagine, as I point to that omission, that people will argue that it isn't fair to judge a book for what it leaves out, for what it didn't intend to do. That "not fair" response, however, is the problem. It tells people who object to being left out or misrepresented, to go away. This book is "not for you."

This particular book is symbolic of all that is wrong with children's literature right now. A Fine Dessert provides children with a glossy view of this country and its history that is, in short, a lie about that history. We should hold those who create literature for children to a standard that doesn't lie to them.

What can we do about that lie? Use it, as Elisa Gall suggested in her blog post, when she wrote:

The only time I’d imagine selecting this book for classroom use would be to evaluate it collaboratively using an anti-bias lens (like the guide by Louise Derman-Sparks found here).

_______________________

Update: November 2, 2015

As I see blog posts and media coverage of this book, I'll add them here. If you know of others, let me know (update on Nov 14, I added additional links and sorted them into distinct categories). I'm adding them by the dates on which they went online, rather than the dates when I read them myself.

This set of blog posts and news articles are primarily about the book and controversy. A Fine Dessert is not unique. For hundreds of years, those who are misrepresented in children's or young adult literature have been objecting to those misrepresentations.

This set of links is to items about a 2016 picture book, A Birthday Cake for George Washington, which also depicts enslaved people, smiling.

Eds. Note, Nov 1, 2015:

Emily Jenkins, the author of A FINE DESSERT issued an apology this morning, posting it at the Calling Caldecott page and at Reading While White. Here are her words, from Reading While White:

This is Emily Jenkins. I like the Reading While White blog and have been reading it since inception. As the author of A Fine Dessert, I have read this discussion and the others with care and attention. I have come to understand that my book, while intended to be inclusive and truthful and hopeful, is racially insensitive. I own that and am very sorry. For lack of a better way to make reparations, I donated the fee I earned for writing the book to We Need Diverse Books.

Eds. Note, Nov 2, 2015:

I'm seeing influential people in children's literature--from librarians to academics--decrying the discussion of A Fine Dessert as one in which people are "tearing each other apart" or "tearing this book to pieces."

For literally hundreds of years, African American families have been torn apart. African Americans are objecting to the depiction of slavery in A Fine Dessert.

Please have some empathy for African American parents whose lives and the lives of their children and ancestors is one that is characterized by police brutality, Jim Crow, and the brutal violence of being enslaved.

If you wish to use a picture book to teach young children about slavery, there are better choices. Among them is Don Tate's POET: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton. Watch the book trailer. Buy the book. Use it.

Eds. Note, Nov. 4, 2015:

Daniél Jose Older was on a panel this weekend at the 26th Annual Fall Conference of the New York City School Library System. The conference theme was Libraries for ALL Learners, and the panel he was on "The Lens of Diversity: It is Not All in What You See." The panel included Sophie Blackall. Last night, Daniel tweeted about it and later storified the tweets. He also uploaded a video of his remarks:

Eds. Note, Nov. 4, 2015:

Daniél Jose Older was on a panel this weekend at the 26th Annual Fall Conference of the New York City School Library System. The conference theme was Libraries for ALL Learners, and the panel he was on "The Lens of Diversity: It is Not All in What You See." The panel included Sophie Blackall. Last night, Daniel tweeted about it and later storified the tweets. He also uploaded a video of his remarks:

At Reading While White, an African American woman wrote:

What I see as a black woman is a skilled house slave training a slave girl how to be a proper house servant for the master's family. This skill actually would make her more valuable on the market, so it is important that she learns well. The master would usually have them doing small things like picking up garbage at 3 and fully laboring by 7 years old, so you have the age right. It's likely she would have never known her mother and was being trained to be a proper house slave by a woman she didn't know.The woman would likely be strict, maybe even beating the girl herself if a mistake was made on this dessert, for she too would suffer if it were not right. The girl would know she was property by then and the "beat" you mentioned would be the pace of her heart, for fear of the punishment, if she made a mistake.

Thursday, October 29, 2015

Not recommended: A FINE DESSERT by Emily Jenkins and Sophie Blackall

Some months ago, a reader asked me if I'd seen A Fine Dessert: Four Centuries, Four Families, One Delicious Treat written by Emily Jenkins, and illustrated by Sophie Blackall. The person who wrote to me knows of my interest in diversity and the ways that Native peoples are depicted---and omitted--in children's books. Here's the synopsis:

In this fascinating picture book, four families, in four different cities, over four centuries, make the same delicious dessert: blackberry fool. This richly detailed book ingeniously shows how food, technology, and even families have changed throughout American history.

In 1710, a girl and her mother in Lyme, England, prepare a blackberry fool, picking wild blackberries and beating cream from their cow with a bundle of twigs. The same dessert is prepared by a slave girl and her mother in 1810 in Charleston, South Carolina; by a mother and daughter in 1910 in Boston; and finally by a boy and his father in present-day San Diego.

Kids and parents alike will delight in discovering the differences in daily life over the course of four centuries.

Includes a recipe for blackberry fool and notes from the author and illustrator about their research.

Published this year, A Fine Dessert arrives in the midst of national discussions of diversity. It is an excellent example of the status quo in children's literature, in which white privilege drives the creation, production, and review of children's and young adult literature.

A Fine Dessert is written and illustrated by white people.

A Fine Dessert is published by a major publisher.

A Fine Dessert, however, isn't an "all white book."

As the synopsis indicates, the author and illustrator included people who are not white. How they did that is deeply problematic. In recent days, Jenkins and Blackall have not been able to ignore the words of those who find their book outrageous. Blackall's response on Oct 23rd is excerpted below; Jenkins responded on October 28th.

~~~~~

The Horn Book's "Calling Caldecott" blog launched a discussion of A Fine Dessert on September 23, 2015. Robin Smith opened the discussion with an overview of the book that includes this paragraph:

Blackall and Jenkins could have avoided the challenge of setting the 1810 scene on the plantation. They did not. They could have simply chosen a family without slaves or servants, but they did not. They clearly approached the situation thoughtfully. The enslaved daughter and mother’s humanity is secure as they work together and enjoy each other, despite their lack of freedom. In the 1810 table scene — the only time in the book when the cooks don’t eat the dessert at the dinner table — each of the African American characters depicted has a serious look on his or her face (i.e., there is no indication that anyone is enjoying their work or, by extension, their enslavement) while the children in the family attend to their parents and siblings or are distracted by a book or a kitty under the table. In its own way, the little nod to books and pets is also a nod to the privilege of the white children. They don’t have to serve. They don’t have to fan the family. They get to eat. Hidden in the closet, the African American mother and daughter have a rare relaxed moment away from the eyes of their enslavers.

Smith also wrote:

Since I have already read some online talk about the plantation section, I assume the committee will have, too. I know that we all bring our own perspectives to reading illustrations, and I trust that the committee will have a serious, open discussion about the whole book and see that the choice to include it was a deliberate one. Perhaps the committee will wish Blackall had set her second vignette in a different place, perhaps not. Will it work for the committee? I have no idea. But I do know that a large committee means there will be all sorts of readers and evaluators, with good discussions.

The "online talk" at that time was a blog post by Elisa Gall, a librarian who titled her blog post A Fine Dessert: Sweet Intentions, Sour Aftertaste. On August 4th, she wrote that:

It’s clear that the creators had noble goals, and a criticism of their work is just that—a criticism of the book (not them). But despite the best of intentions, the result is a narrative in which readers see slavery as unpleasant, but not horrendous.The Calling Caldecott discussed continued for some time. On October 4th, Jennifer wrote:

Based on the illustrations, there are too many implications that should make us as adults squirm about what we might be telling children about slavery:1) That slave families were intact and allowed to stay together.2) Based on the smiling faces of the young girl…that being enslaved is fun and or pleasurable.3) That to disobey as a slave was fun (or to use the reviewers word “relaxed”) moment of whimsy rather than a dangerous act that could provoke severe and painful physical punishment.On October 5th, Lolly Robinson wrote that:

... the text and art in the book need to be appropriate for the largest common denominator, namely that younger audience.Robinson's words about audience are the key to what is wrong with this book. I'll say more about that shortly.

On October 23rd, Sophie Blackall--the illustrator--joined the discussion at Calling Caldecott, saying she had decided to respond to the criticism of how she depicted slavery. She linked to her blog, where she wrote:

Reading the negative comments, I wonder whether the only way to avoid offense would have been to leave slavery out altogether, but sharing this book in school visits has been an extraordinary experience and the positive responses from teachers and librarians and parents have been overwhelming. I learn from every book I make, and from discussions like these. I hope A Fine Dessert continues to engage readers and encourage rewarding, thought provoking discussions between children and their grown ups.In that comment, Blackall talks about school visits and positive responses from teachers, and librarians, and parents. My guess? Those are schools with primarily white students, white teachers, white librarians, and white parents. I bring that up because, while Blackall doesn't say so, my hunch is she's getting that response, in person, from white people. That positive response parallels what I see online. It is white women that are praising this book. In some instances, there's a nod to the concerns about the depiction of slavery, but the overwhelming love they express is centered on the dessert that is made by four families, in four centuries.

Praise is not the response from Black women and mothers.

On October 25 at 12:37, fangirlJeanne's, who identifies as a Polynesian woman of color, sent a tweet that got right to the heart of the matter. She wrote that "Authors who assume a young reader doesn't know about slavery or racism in America is writing for a white reader." In a series of tweets, she wrote about the life of children of color. With those tweets, she demonstrated that the notion of "age appropriate" content is specific to white children, who aren't amongst the demographics that experienced--and experience--bullying and bigoted attacks.

At 1:00, she shared an image of the four pages in the book that Sophie Blackall has in her blog post, saying that these illustrations make her sick and sad:

The conversation about the book grew larger. Some people went to Blackall's post and submitted comments that she subsequently deleted. The explanation for why she deleted them rang hollow. And then sometime in the last 24 hours, she added this to the original blog post:

This blog has been edited to add the following:

It seems that very few people commenting on the issue of slavery in A Fine Dessert have read the actual book. The section which takes place in 1810 is part of a whole, which explores the history of women in the kitchen and the development of food technology amongst other things. A Fine Dessert culminates in 2010 with the scene of a joyous, diverse, inclusive community feast. I urge you to read the whole book. Thank you.Clearly, Blackall is taking solace in Betsy Bird's You Have to Read the Book. Aligning herself with that post is a mistake made in haste, or--if she read and thought about the thread--a decision to ignore the voices of people of color who are objecting to her depiction of slavery.

My hope is that the people on the Caldecott committee are reading the conversations about the book and that they will subsequently choose not to name A Fine Dessert as deserving of Caldecott recognition.

The book is going to do well, regardless of the committee decision. Yesterday, the New York Times named it as one of the best illustrated books of 2015. That, too, speaks to a whiteness that must be examined.

In this post, I've focused on the depictions of slavery. I've not said anything about Native people and our absence from Jenkins and Blackall's historical narrative. Honestly, given what they did with slavery, I'm glad of that omission. I'm reminded of Taylor, a fifth grader who was learning to think critically about Thanksgiving. She wrote "Do you mean all those Thanksgiving worksheets we had to color every year with all those smiling Indians were wrong?" The American settings for A Fine Dessert, of course, are all on land that belonged to Native peoples who were forcibly removed and killed to make way for Americans to raise their families, to pursue their American dreams.

I imagine, as I point to that omission, that people will argue that it isn't fair to judge a book for what it leaves out, for what it didn't intend to do. That "not fair" response, however, is the problem. It tells people who object to being left out or misrepresented, to go away. This book is "not for you."

This particular book is symbolic of all that is wrong with children's literature right now. A Fine Dessert provides children with a glossy view of this country and its history that is, in short, a lie about that history. We should hold those who create literature for children to a standard that doesn't lie to them.

What can we do about that lie? Use it, as Elisa Gall suggested in her blog post, when she wrote:

The only time I’d imagine selecting this book for classroom use would be to evaluate it collaboratively using an anti-bias lens (like the guide by Louise Derman-Sparks found here).

_______________________

Update: November 2, 2015

As I see blog posts and media coverage of this book, I'll add them here. If you know of others, let me know (update on Nov 14, I added additional links and sorted them into distinct categories). I'm adding them by the dates on which they went online, rather than the dates when I read them myself.

This set of blog posts and news articles are primarily about the book and controversy. A Fine Dessert is not unique. For hundreds of years, those who are misrepresented in children's or young adult literature have been objecting to those misrepresentations.

- Aug 4, 2015. A Fine Dessert: Sweet Intentions, A Sour Aftertaste by Elisa Gall at Trybrary

- Sept 23, 2015. A Fine Dessert (Calling Caldecott discussion) by Robin Smith at The Horn Book

- Oct 30, 2015. The Kids' Book 'A Fine Dessert' Has Award Buzz--And Charges of Whitewashing Slavery by Leah Donnella at NPR

- Oct 31, 2015. On Letting Go at Reading While White

- Oct 31, 2015. Oh, Kelly at Jenny and Kelly Read Books

- Nov 1, 2015. The "Diversity Agenda People" at Ellen Oh's blog

- Nov 3, 2015. A Slightly Different Take by Varian Johnson

- Nov. 4, 2015. Daniel José Older on A Fine Dessert (video) by Daniel José Older at YouTube

- Nov 3, 2015. Emily Jenkins Apologizes for "A Fine Dessert" by Lauren Barack at School Library Journal

- Nov. 4, 2015. Full Panel: Lens of Diversity (video) by Daniel José Older's at YouTube

- Nov 4 2015. When Will We Stop Allowing 'Good Intentions' to be An Excuse for Whitewashing History? by Allison McGevna

- Nov 4, 2015. Children's author sorry for 'racial insensitivity' in picture book showing smiling slaves at The Guardian

- Nov 4, 2015. The dessert, by the way, is blackberry fool by Edith Campbell at Crazy QuiltEdi

- Nov 5, 2015. Children's author apologises for 'racially insensitive' smiling slaves picture book by Jess Denham at the Independent

- Nov 5, 2015. Critically acclaimed children's book criticized for depicting 'happy slaves' by Sadaf Ahsan at the National Post.

- Nov 6, 2015. Judging a Book by the Smile of a Slave by Jennifer Schuessler at The New York Times

- Nov 6, 2015. Thoughts: A Fine Dessert by Emily Jenkins and Sophie Blackall by Nafiza at The Book Wars

- Nov 7, 2015: Reflecting on a Fine Dessert by Kiera Parrot of School Library Journal

- Nov 10, 2015. Children's Book Depicts Smiling Slaves, Stirs Controversy by Kenrya Rankin Naasel at Colorlines

- Nov 10, 2015. A not so fine dessert at The Field Negro

- Nov 14, 2015. Episode 71 podcast at Interracial Jawn (at the 50:25 minute mark)

- Dec 10, 2015. Caldecott Medal Contender: A Fine Dessert by Sam Juliano at Wonders in the Dark (h/t: Elisa Gall)

- Undated. Texas Library Association's Statement on A Fine Dessert being listed on its 2016-2017 Texas Bluebonnet Award Master List

This set of links are primarily on what-to-do about the controversy over A Fine Dessert and, broadly speaking, diversity in children's/young adult literature. A lot of them echo previous writings. For decades, people have been writing about how writers and illustrators and editors can inform themselves so they don't stereotype or misrepresent those who are not like themselves, and people have been writing about what we, as readers (parents, teachers, and librarians) can do to encourage publishers to publish books that do not misrepresent our distinct cultures.

- Oct 27, 2015. "You Have to Read the Book" by Elizabeth Bird at School Library Journal

- Oct 30, 2015. "Editorial: We're Not Rainbow Sprinkles" by Roger Sutton at Horn Book

- Nov 2, 2015. "What We Talk about When We Talk about Children's Books" by Nina Lindsay at School Library Journal

- Nov 3, 2015. "Keeping the Channel Open" by Teri Lesesne at Professor Nana

- Nov 3, 2015. "Can We Talk about Solutions?" by Roxanne Feldman at Fairrosa Cyber Library

- Nov 3, 2015. "Do the Hard Work of Getting It Right" by Kimberly Brubaker Bradley at One Blog Now

- Nov 6, 2015. "The Power of Social Media to Change Children's Literature" by Debbie Reese at American Indians in Children's Literature

- Nov 10, 2015. "Kidlit Authors and Illustrators: Time To Step Up" by K. Tempest Bradford at tempest.fluidartist.com

- Nov 29, 2015. "A Fine Dessert... What Does This Mean for Teachers?" by Franki at A Year of Reading

- Dec 8, 2015. "On Needing Diverse Books" by Marion Dane Bauer at her blog

- Undated. "An Editor's Response" by Yolanda Scott, at CBC Diversity

- Jan 4, 2016. "Smiling Slaves in a Post-A Fine Dessert World", by Vicky Smith at Kirkus

- Jan 6, 2016. "What Will They Say" by Debbie Reese at American Indians in Children's Literature

- Jan 6, 2016. "A proud slice of history." by Andrea Davis Pinkney at On Our Minds (Scholastic blog)

- Jan 8, 2016. "On the Depiction of Slavery in Picture Books" by Nathalie Mvondo at Multiculturalism Rocks

- Jan 13, 2016. "Book Review: A Birthday Cake for George Washington" by Edith Campbell at Crazy QuiltEdi

- Jan 13, 2016. "So Scholastic is publishing..." by @LeslieMac on Twitter

Thursday, October 01, 2015

Big News about Hoffman's AMAZING GRACE

Eds. note (10/2/2015): See update at bottom. It appears the change is only to the U.S. edition.

In a comment to his post about weeding books, Roger Sutton said that Horn Book just received the 25th anniversary edition of Amazing Grace and that the page on which Grace is shown playing Indian is gone (she's pretending to be Longfellow's Hiawatha). Here's his comment:

This is the illustration he's talking about. It was in the original version of the book, published by Dial in 1991. The author is Mary Hoffman; the illustrator is Caroline Binch:

For those who don't know the book, the main character is a girl named Grace who wants to be Peter Pan in the play her class is going to do. Other kids tell her she can't be Peter because she's a girl and he's a boy, and, that she's Black and he's White. Stung--as any kid would be--she imagines herself in all kinds of roles, including Hiawatha. That she's "by the shining Big-Sea-Water" tells us she is imagining herself as the Hiawatha of Longfellow's imagination (there was, in fact, a real person named Hiawatha).

But see how Grace "plays" Hiawatha? In a stereotypical way. She sits cross legged, torso bare, arms crossed and raised up (I don't know why so many statues show Indians with arms crossed and lifted off the chest that way), barefoot, with a painted face and stoic look.

Amazing Grace came out in 1991. In 1992, a person from whom I've learned a great deal, wrote about it. That person: Ginny Moore Kruse. In her article "No Single Season: Multicultural Literature for All Children, published in Wilson Library Bulletin 66 30-3, she wrote:

This change is big news in children's literature. I'm grateful to Roger for sharing it. But let's return to his words. Roger suggested that the absence of Grace/Hiawatha in the new edition is the result of "public shaming."

Its absence can be seen as the result of public shaming---but it also be seen as a a step forward in what we give to children.

Might we say it is gone because its author, illustrator, and publisher decided that the self-esteem of Native children matters? And, maybe, they decided that having it in there was a disservice to non-Native readers, too, skewing what they know about Native peoples? Maybe they just decided it was dated, and in an effort to market the book to today's readers, that page would hurt sales.

Today, I wish I was near Ginny's hometown. I'd call her and see if she wanted to join me for a cup of tea. I'm sure it'd be a delightful conversation.

Updated on October 2, 2015 at 9:23 AM

Librarian Allie Jane Bruce wrote to tell me about a review of Amazing Grace at the UK website, Mirrors, Windows, and Doors. Based on what I read in the review, there are two versions of the 25th anniversary edition of Amazing Grace. The one Roger Sutton has is the US edition. The one in the UK remains unchanged. Here's an excerpt of the UK review:

I guess that the people involved in the 25th anniversary edition think it is ok to let kids in the UK have that page. Obviously, I disagree.

This, however, is familiar. In 2010, a British production of Peter Pan was slated for Canada. Changes were made to it in an effort to be sensitive to First Nations people. Given the debased depictions of Native peoples in kids books imported from the UK to the US, I think it is wrong to leave that page in Amazing Grace. Worse than wrong, actually. It is a disservice to the children whose stereotypical ideas of Native people are affirmed by that page, and a disservice to those who learn that image for the first time, when they read Amazing Grace.

In a comment to his post about weeding books, Roger Sutton said that Horn Book just received the 25th anniversary edition of Amazing Grace and that the page on which Grace is shown playing Indian is gone (she's pretending to be Longfellow's Hiawatha). Here's his comment:

This is the illustration he's talking about. It was in the original version of the book, published by Dial in 1991. The author is Mary Hoffman; the illustrator is Caroline Binch:

For those who don't know the book, the main character is a girl named Grace who wants to be Peter Pan in the play her class is going to do. Other kids tell her she can't be Peter because she's a girl and he's a boy, and, that she's Black and he's White. Stung--as any kid would be--she imagines herself in all kinds of roles, including Hiawatha. That she's "by the shining Big-Sea-Water" tells us she is imagining herself as the Hiawatha of Longfellow's imagination (there was, in fact, a real person named Hiawatha).

But see how Grace "plays" Hiawatha? In a stereotypical way. She sits cross legged, torso bare, arms crossed and raised up (I don't know why so many statues show Indians with arms crossed and lifted off the chest that way), barefoot, with a painted face and stoic look.

Amazing Grace came out in 1991. In 1992, a person from whom I've learned a great deal, wrote about it. That person: Ginny Moore Kruse. In her article "No Single Season: Multicultural Literature for All Children, published in Wilson Library Bulletin 66 30-3, she wrote:

Are the book's multiple themes so welcome that the act of "playing Indian" escaped comment by most U.S. reviewers...that critics relaxed their standards for evaluation? No, such images recur so frequently that when they do, nobody notices. Well, almost nobody but the children who in real life are Indian.

Claiming that only American Indian children are apt to notice "playing Indian," "sitting Indian style," or picture book animals "dressed up" like American Indians does not excuse the basic mistake. Self-esteem is decreased for the affected peoples, an accurate portrayals are skewed for everyone else.

This change is big news in children's literature. I'm grateful to Roger for sharing it. But let's return to his words. Roger suggested that the absence of Grace/Hiawatha in the new edition is the result of "public shaming."

Its absence can be seen as the result of public shaming---but it also be seen as a a step forward in what we give to children.

Might we say it is gone because its author, illustrator, and publisher decided that the self-esteem of Native children matters? And, maybe, they decided that having it in there was a disservice to non-Native readers, too, skewing what they know about Native peoples? Maybe they just decided it was dated, and in an effort to market the book to today's readers, that page would hurt sales.

Today, I wish I was near Ginny's hometown. I'd call her and see if she wanted to join me for a cup of tea. I'm sure it'd be a delightful conversation.

Updated on October 2, 2015 at 9:23 AM

Librarian Allie Jane Bruce wrote to tell me about a review of Amazing Grace at the UK website, Mirrors, Windows, and Doors. Based on what I read in the review, there are two versions of the 25th anniversary edition of Amazing Grace. The one Roger Sutton has is the US edition. The one in the UK remains unchanged. Here's an excerpt of the UK review:

The double-page that shows Grace as Hiawatha and then as ‘Mowgli in the back garden jungle’ does, however, need to be held up as a reminder that breadth of experience through reading is important for young children: whilst Grace’s story highlights a can-do attitude and the notion that you can be whatever you want to be because of what you do not what you are, the stereotypes that have been passed down through some of these classic stories can only be broken by ensuring that children read contemporary stories set within the cultures they represent. There is still too much of a dislocation in the UK between dressing up in a feathered headdress with a painted face and awareness of how that sits within contemporary Native American culture.

I guess that the people involved in the 25th anniversary edition think it is ok to let kids in the UK have that page. Obviously, I disagree.

This, however, is familiar. In 2010, a British production of Peter Pan was slated for Canada. Changes were made to it in an effort to be sensitive to First Nations people. Given the debased depictions of Native peoples in kids books imported from the UK to the US, I think it is wrong to leave that page in Amazing Grace. Worse than wrong, actually. It is a disservice to the children whose stereotypical ideas of Native people are affirmed by that page, and a disservice to those who learn that image for the first time, when they read Amazing Grace.

Sunday, January 05, 2014

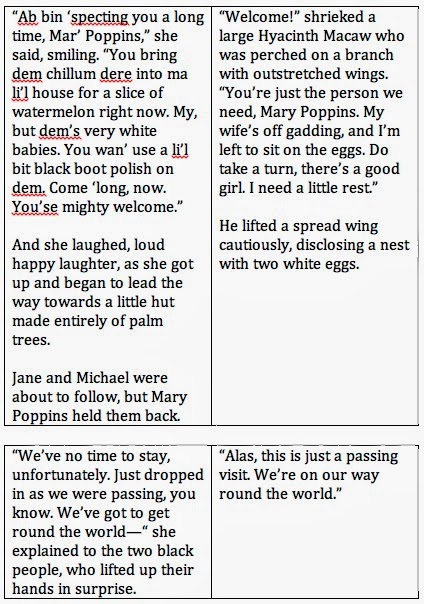

Travers (author of Mary Poppins): "I lived with the Indians..."

With the release of Saving Mr. Banks, my colleagues in children's literature are responding to Disney's presentation of P. L. Travers. In reading Jerry Griswold's '"Saving Mr. Banks" but throwing P.L. Travers Under the Bus,' I read that Travers had spent time on the Navajo reservation during WWII. In his interview of Travers in the Paris Review, I read this:

I lived with the Indians, or rather I lived on the reservations, for two summers during the war. John Collier, who was then the Commissioner of Indian Affairs, was a great friend of mine and he saw that I was very homesick for England but couldn’t go back over those mined waters. And he said, “I’ll tell you what I’ll do for you. I’ll send you to live with the Indians.” “That’s mockery,” I replied. “What good will that do me?” He said, “You’ll see.”

Collier---a name well known to us Pueblo people! Intrigued, I continued to read that interview. In it, she says that she liked the "wide, flounced Spanish skirts with little velvet jackets" that the Navajo women were wearing, and so, they made a skirt and jacket for her. Is there, I wonder, a photo of her in that skirt and jacket? For those of you who aren't familiar with these items, here's a board book with a child in that clothing:

In the interview, Travers also said "The Indians in the Pueblo tribe gave me an Indian name and they said I must never reveal it. Every Indian has a secret name as well as his public name. This moved me very much because I have a strong feeling about names, that names are part of a person, a very private thing to each one." Interesting! I have a Tewa (name of our language) name, but it is not secret. What pueblo, I wonder, did she visit? At the time of her visit, did that pueblo have secret names?

I've got lots of questions! I'll add them, and answers I find, in the coming hours and days. If you're a scholar of fan of Travers and can send me info about her time with Navajo and Pueblo people, please do!

Update: Sunday, January 5, 2014, 12:58 PM

That jewelry stood out in her granddaughter's memory. At the 50:00 mark of the documentary, Kitty remembers her grandmother "wearing all this extraordinary silver jewelry." At about that point in the documentary there is a clip of Travers at her typewriter. You can definitely see the jewelry is turquoise and silver. Whether it is Navajo or Pueblo in origin is hard to tell:

In the documentary, I learned that by 1959, Disney had spent 15 years trying to get the rights to make the movie. That means 1945, which fits with when she was in New Mexico and Arizona. Thus far, I haven't seen anything about why she was in the US at that time. Was it to meet with Disney?!

Next on my research exploration: reading Valerie Larson's biography, Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The Life of P.L. Travers.

Before moving on to do that, I'm inserting a link to a short piece I did on Mary Poppins a couple of years ago: "You Will Not Behave like a Red Indian, Michael!"

Update: Monday, January 6, 2014, at 12:20 PM CST

Yesterday afternoon and evening I read the parts of Larson's biography that are about Travers being in New Mexico. It was not, as I'd surmised, to visit Disney. The following notes are from my reading of Larson's biography (Mary Poppins, She Wrote: The Life of P.L. Travers).

Travers was in the US due to the war.

In 1939, Travers adopted a baby boy named Camillus (in the BBC documentary, there's a lot of attention on the adoption. She didn't adopt his twin; when Camillus learned about his twin, he was 17. Until then, he'd thought he was born to Travers and that his father had died. Learning the truth caused problems between the two.) This was the period during the war in which people were leaving London for safer places.

In 1940, Travers left, too, on a ship that carried 300 children to Canada. She served as escort for some of the children. Once in Canada, she flew to New York City. She had women friends there: Jessie Orage and Gertrude Hermes. Jessie moved to Santa Fe soon after to be with "a community of Orage and Gurdjieff followers." Prior to her move, she'd been very close to AE (Irish writer George William Russell), who knew John Collier (Larson calls him a 'minister' in Roosevelt's administration. Collier's position was actually Commissioner of Indian Affairs).

In the summer of 1941, Travers spent most of her time in Maine. In January of 1942, Jessie visited her in New York. "Gert" (Gertrude Hermes) and Travers separated that year. In 1943, her Mary Poppins Opens the Door was published and she was feeling very homesick.

Collier suggested she spent a summer or two on an Indian reservation. At first resistant to the idea, Larson writes that Travers (note: the following excerpts are from Chapter 10 in the ebook w/o page numbers):

later felt Collier's offer came as a kind of magic. The next two summers were to be among the great experiences of her life. She moved from the gray reality of New York to the brilliantly colored fantasy of the southwest, just as Poppins moves through a mirage door from her earthly Cherry Tree Lane to her heavenly friends in the sky. Here, Pamela discovered what so many artists and writers had found before and after her: spiritual peace and meaning within a beautiful landscape, brittle, red, gray-green.Her first visit was in September of 1943, to Santa Fe, where Jessie was living. Though she may have visited the Navajo reservation then, Larson makes no mention of it. That came later, in the summer of 1944, when Travers was in the southwest for five months. Larson writes:

She had accepted John Collier's suggest that she live for some weeks in Window Rock, a tiny Navajo settlement in Arizona, near the New Mexico border. It looked like a train stop at the end of the world.And,

Pamela like to say she spent the summer on a reservation, but photographs in her albums show that she and Camillus lived in a western-style building that Pamela indicated in one interview was a boarding house. On the grounds in front, grinning for the camera, Camillus sat perched on the back of Silver, a white horse.

Larson writes that Travers was driven to the "reservations" (reservation is correct) where she tried to "speak little but hear much." During those storytelling sessions, Larson writes that Travers was "folding herself away so she did not seem to be listening to the Navajos' stories. She wanted to share the dances and songs, share the silence." (Note: I don't know what to make of that... perhaps she was trying to absorb what was happening around her in some metaphysical way.)

She also went to puberty ceremonies for Navajo girls and liked the matriarchal society. Larson writes:

Pamela took notes of the Navajo ways, religion, hierarchy, spiritual leaders: first the Holy Ones who can travel on a sunbeam or the wind, the Changing Woman, the earth mother who teaches people to live in harmony with nature, and her children, the Hero Twins, who keep enemies away.

She saw relationships between Navajo stories and those of other people around the world. She ate in hogans, and, wrote that Camillus:

"was taken by the hand by grave red men, gravely played with, and, ultimate honor, gravely given an Indian name. Its strange beautiful syllables mean "Son of the Aspen."

Travers was also given a name, but, Larson writes:

Pamela was given a secret Indian name and told "I must never reveal it and I have never told a soul." Her secret name, she said, "bound her to the mothering land," that is the land of the Earth Mother--her own motherland was far away.

Travers also went out to ceremonial dancing that took place at night. She rode blue jeans, boots, and cowboy shirts as she rode a horse in Canyon de Chelly. As noted above, she liked the skirts and jackets Navajo women wore. Larson writes:

From these days she adopted two fashions she wore until old age: tiered floral skirts and Indian jewelry, turquoise and silver, with bracelets stacked up each forearm like gauntlets.

Travers wrote to Jessie that was returning to Santa Fe. On July 19th, Jessie visited her in a Santa Fe hotel and drove her to the writer/artist colony in Taos. In September she helped Travers find a place to live in Santa Fe. In November, Travers returned to New York and in March, moved back to London. Larson refers to the bracelets a few additional times in the remainder of the book.

Next up? Some analysis and hard thinking about the ways that Travers depicted/incorporated Native content in her stories.

Update: Tuesday, January 7, 2014

Before the analysis, I'll take a few minutes to note that the documentary "PL Travers: The Real Mary Poppins" says that Disney was, in fact, in touch with Travers in 1944. At around the 2:00 mark of this segment, you'll hear that Disney began negotiations with her in January. The documentary shows an inter-office communication dated January 24, 1944, with "Mary Poppin Stories" as the subject. There's a second item--a letter to Travers--dated February 1944 at around 2:10 in the documentary. It references Travers plan to visit Arizona and suggests a meeting. If you're interested in Travers and her relationship with Disney as they developed the script and movie, watch the video. It has screen shots of letters she wrote, and audio clips, in which she objected to aspects of the script.

In part 4 of that documentary, one of her friends talks about how Travers studied dance of other cultures because that was a way they told stories. At 4:51, the person who did choreography for the Disney film speculates that her interest in dance is evident in her stories, where dance and flying figures prominently. At 4:51 in the segment, there's a video clip of an Eagle Dance! It is a Pueblo dance, not a Navajo one. The choreographer talks about her lectures and then the segment goes to an audio recording of her from a talk she gave at Smith College in 1966 in which she says:

When I was in Arizona living with the Indians for two summers during the war, they gave me an Indian name and they said 'we give you this so that you will never never tell it to anybody. Anybody can know your other name but this name must never be spoken' and I've never spoke of it from that day to this. There is something very strange and mysterious about ones names. I myself always tremble when people I don't know very well take my Christian name. I tremble inside. I don't like it.

All through that audio, there are clips of the eagle dance. Are those clips from her own footage? I recognize the Eagle Dance, and I recognize Taos Pueblo, too.

Patricia Feltman, her friend, says that Travers spent two summers with the Navajo Indians, who made the jewelry she wore every day of her life.

That's it for now.... More later.

Update: Wednesday, January 8, 2013, 1:57 PM CST

Of interest to me is the ways in which Travers wrote about what is generally called "other." This happens in the Bad Tuesday chapter in the first book, published in 1934. It was turned into a Little Golden Book in 1953. Here's screen captures of two pages in the part of the book (I don't have the book myself) in which Mary Poppins and the children go West using the compass. The source for my screen captures is kewzoo's account at flickr.

As yet, I don't have the original book to compare the words in it to the words in the Little Golden Book above. I don't find any of that text in the 2007 Houghton Mifflin Harcourt copy that I'm reading. Those pages in which they travel using the compass were completely rewritten. As she says below in the interview, she kept the plot (of traveling) but apparently changed the people they met to animals. In the revised chapter, when they're in the West, they see dolphins, not Indians. That this is a revised chapter is clearly marked in the Table of Contents:

I turn now, to two of Travers' responses to objections. The first one was published in 1977, and the second one in 1982.

Travers granted an interview to Albert V. Schwartz, who was at the time of the interview, an Assistant Professor of Language Arts at Richmond College in State Island. His account is available in Cultural Conformity in Books for Children, edited by Donnarae MacCann and Gloria Woodard, published by Scarerow Press in 1977.

When Schwartz learned that the chapter had been revised, he got in touch with the publisher, Harcourt Brace Jovanovich for details. He learned that the revisions took place in the 1972 paperback, at Travers' request. Schwartz then got in touch with Travers and set up the interview. He told her that the Council on Interracial Books for Children had been receiving complaints about stereotypical presentations of Africans, Chinese, Eskimos, and American Indians. Here's a quote from Schwartz's chapter (p. 135):

Sitting tall and tense, Pamela Travers was aware of every word as she spoke: "Remember Mary Poppins was written a long time ago when racism was not as important. About two years ago, a schoolteacher friend of mine, who is a devotee of Mary Poppins and reads it constantly to her class, told me that when she came to that part it always made her squirm if she had Black children in her class. I decided that if that should happen, if even one Black child were troubled, or even if she were troubled, then I would have to alter it. And so I altered the conversation part of it. I didn't alter the plot of the story. When the next edition, which was the paperback, came out, I also altered one of two things which had nothing to do with 'picaninny' talk at all.

"Various friends of mine, artists and writers, said to me, 'No, no! What you have written you have written. Stand by it!' But, I thought, no, if the least of these little ones is going to be hurt, I am going to alter it!"

A few paragraphs later is this:

"I am not really convinced that any harm is done," she continued. "I remember when I was first invited to New York by a group of schoolteachers and librarians, amongst whom were many Black teachers. We met at the New York Public Library. I had thought that they expected me to talk to them, but no, on the contrary, they wanted to thank me for writing Mary Poppins because it had been so popular with their classes. Not one of them took the opportunity--if indeed they noticed it--to talk about what you've mentioned in 'Bad Tuesday.'"

The Irish have an expression: “Ah, my grief!” It means “the pity of things.” The objections had been made to the chapter “Bad Tuesday,” where Mary Poppins goes to the four points of the compass. She meets a mandarin in the East, an Indian in the West, an Eskimo in the North, and blacks in the South who speak in a pickaninny language. What I find strange is that, while my critics claim to have children’s best interests in mind, children themselves have never objected to the book. In fact, they love it. That was certainly the case when I was asked to speak to an affectionate crowd of children at a library in Port of Spain in Trinidad. On another occasion, when a white teacher friend of mine explained how she felt uncomfortable reading the pickaninny dialect to her young students, I asked her, “And are the black children affronted?” “Not at all,” she replied, “it appeared they loved it.” Minorities is not a word in my vocabulary. And I wonder, sometimes, how much disservice is done children by some individuals who occasionally offer, with good intentions, to serve as their spokesmen. Nonetheless, I have rewritten the offending chapter, and in the revised edition I have substituted a panda, dolphin, polar bear, and macaw. I have done so not as an apology for anything I have written. The reason is much more simple: I do not wish to see Mary Poppins tucked away in the closet.Interesting, isn't it? I'm still reading and thinking and will share more later. If you have other items to point me to, please do! And for those who have already done so, thank you!

Update: Thursday, January 9, 12:58 PM CST

Editors note, Jan 10, 2014, 5:26 PM CST --- the excepts described herein as 'original' are from a 1963 edition published by HBJ, prior to the revisions. From K.T. Horning, I've just learned that there were TWO revisions. In the first one, the human characters remained but the Black dialect was changed to what Travers described as "Proper English." I do not have a copy of "Bad Tuesday" that K.T. Horning referenced (in a comment on Facebook). If you do have that copy, please scan and send to me if you can!

Thanks to librarians, I now have the original chapter. Specifically, thank you, Michelle Willis! Michelle sent me the color scan of the compass and the chapter from which I created the side-by-side excerpts.

First up is the Mary Shepherd's illustration of the compass (illustrations for later versions were changed to match the changes to the text):

At the start of the Bad Tuesday chapter, Michael has gotten up on the wrong side of the bed. He's doing naughty things. Later in the day, Mary Poppins has taken Jane and Michael out for a walk. Mary Poppins sees the compass on the ground and tells Michael to pick it up. He wonders what it is, and she tells him it is for going around the world. Michael is skeptical, so Mary Poppins set out to prove to him that the compass can, indeed, take them around the world.

She begins their trip by saying "North!" The air starts to get very cold and the kids close their eyes. When they open them, they're surrounded by boulders of blue ice. Jane asks what has happened to them. (Below is the complete text from both versions for this section of the book. Blank boxes mean there was no corresponding text in the revision.) Here's an enlargement of the illustration for North:

|

| Enlargement of Eskimo, illustration by Mary Shepherd |

Next update? The South!

Update: Thursday, January 9, 2014, 2:25 PM CST

(I apologize for different size of the side-by-side images. I'm entering the text into a table in Word and then doing a screen capture according to the size of the boxes. It is clumsy, but it is the only way I know of for getting the text aligned side-by-side in Blogger.) An enlargement of "South" on the compass is followed by text:

|

| Enlargement of Mary Shepherd's illustration for South |

Here's the illustration for East, followed by the text:

|

| Mary Shepherd's illustration of East |

That's it for now. My next update will be West.

Update: Friday, January 10, 2014, 4:12 PM CST

Here's an enlargement of West on the compass:

|

| Mary Shepherd's illustration of West |

And here's the side-by-side comparisons of the original and revised versions of the portion of the book about West:

After that they head back home. As the afternoon wore on, Michael got naughtier and naughtier. Mary Poppins sent him to bed. Just as he climbed into bed he saw the compass on the chest of drawers and brought it into bed with him, thinking he would travel the world himself. He says "North, South, Eaast, West!" and then...

Then he hears Mary Poppins telling him calmly, "All right, all right. I'm not deaf, I'm thankful to say--no need to shout." He realizes the soft thing is his own blanket. Mary Poppins gets him some warm milk. He sips it slowly. The chapter ends with Michael saying "Isn't it a funny thing, Mary Poppins," he said drowsily. "I've been so very naughty and I feel so very good." Mary Poppins replies "Humph!" and then tucks him in and goes off to wash dishes.

MY INITIAL THOUGHTS

As the interviews above suggest, Travers made changes, but why? The two interviews differ in her reaction to objections. As far as I've been able to determine, the objections were to her portrayal of Blacks, but if you've seen articles or book chapters that described objections to the other content, do let me know!

The book was written before her trip to the southwest. It seems to me that if she had understood the significance of names (as she says in the interviews), she would have--on her own--revisited the names she gave to the Indians in the West, and she would have come away (after seeing dances) knowing that her depictions of dance were inappropriate. If she'd have been paying attention to the Navajo people (and Pueblo people, if she did indeed visit a Pueblo) as people rather than people-who-tell-stories-and-make-jewelry-and-dance, she would have--all on her own--rewritten that portion of the chapter. She didn't do that, however, until much later.

For now, I think I'll let things simmer and then post some analysis and concluding thoughts later.

In the meantime, submit comments here (or on Facebook). I'd love to hear what you think of all this.

Labels:

Mary Poppins,

Navajo Reservation,

P.L. Travers,

Pueblo,

revised

Wednesday, April 10, 2013

Joan Walsh Anglund's THE BRAVE COWBOY

Several weeks ago, Jo, (she's married to my cousin, Steve) wrote on my Facebook wall (in a comment to my post there about Peggy Parrish's Let's Be Indians) to tell me about Joan Walsh Anglund's The Brave Cowboy.

Jo wrote:

Reading what Jo said, I got a copy of the book from the University of Illinois library, but it didn't have the pages Jo described. The copy I got has a publication year of 2000. The one she had, which she sent to me, is 1959. The publisher is Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Here's the first page with Indians:

Jo wrote:

I found a few of these older books at the thrift store one day; they were about a little boy who likes to dress up like a cowboy. I thumbed through Cowboy and his Friend, all about the little boy and his friend Bear and the adventures they have together. Very cute and harmless so I thought what the heck and got them. I read it to the boys and it was great so we started to read the next one, The Brave Cowboy. I don't know why I didn't flip through it first. The second page of the book shows him ready to shoot the scary half naked Indian. I quickly closed it and told the boys we couldn't read it and put it away. A little further in the book it shows him ready to shoot a large number "wild Indians in his territory." We still have it. Steve said we should keep it and send it to you.A few days later, Jo wrote again to tell me:

My six year old picked up the book the other day and read it. When she was finished she was shaking her head and I asked her what she thought about it. She told me she didn't really like it. I asked her why and she said she was confused about the little cowboy shooting the Indians. It was an interesting moment for me to try to find the right words to talk to her about the pictures in the book.

Reading what Jo said, I got a copy of the book from the University of Illinois library, but it didn't have the pages Jo described. The copy I got has a publication year of 2000. The one she had, which she sent to me, is 1959. The publisher is Harcourt, Brace and Company.

Here's the first page with Indians:

1959

In the 2000 copy I had, the third line of text is different. Instead of "not afraid of Indians," the boy is "not afraid of mountain lions." The Indian is gone from the illustration (replaced by another ornery rustler) and a mountain lion has been added:

And here's the next page on which Indians appear. The text is "Or, maybe he would hunt wild Indians that might be in the territory...":

In the 2000 version, the brave cowboy hunts bank robbers instead of "wild Indians."

The day draws to a close and the brave cowboy "settled down to dream the dreams of all good cowboys" which includes dreaming about Indians:

As I wrote this post, my thoughts turned again and again to the current national discussion on gun control. I doubt that The Brave Cowboy would get republished again, and in my opinion, I think that's a good thing. Kids playing with guns? Even in a story, it's frightening.

The Brave Cowboy is far from the first or only book to undergo revisions like these ones. Two that have been updated (or bowdlerized) are Robert Lawson's They Were Strong and Good and Laura Ingalls Wilder's Little House on the Prairie. At his site, Philip Nel took a look at several others.

Returning to the stereotyping in the 1959 copy of The Brave Cowboy, Jo, Steve, and their kids. First, the children in their home are lucky to have Jo and Steve. They're readers who read critically. They're teaching their children to do that, too. Second, Anglund's book is clearly one that has been updated to remove stereotyping. Third, I wish a note about that sort of updating was noted somewhere in the book. Fourth, I hope the book goes out of print and stays out of print.

Thanks, Jo, for letting me know about this book.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)