address or contain the following topics: human sexuality, sexually transmitted diseases, or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) or acquired immune deficiency syndrome (AIDS), sexually implicit images, graphic presentations of sexual behavior that is in violation of the law, or contain material that might make students feel discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress because of their race or sex or convey that a student, by virtue of their race or sex, is inherently racist, sexist, or oppressive, whether consciously or unconsciously.

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

- Debbie on Social Media

- 2024 American Indian Literature Award Medal Acceptance Speeches

- Native Removals in 2025 by US Government

Saturday, February 19, 2022

Challenges to AN INDIGENOUS PEOPLES' HISTORY OF THE UNITED STATES, FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

Saturday, February 12, 2022

Art Coulson and Madelyn Goodnight's LOOK GRANDMA! NI, ELISI! featured in Reading Rainbow Live

Bo wants to find the perfect container to show off his traditional marbles for the Cherokee National Holiday. It needs to be just the right size: big enough to fit all the marbles, but not too big to fit in his family's booth at the festival. And it needs to look good! With his grandmother's help, Bo tries many containers until he finds just the right one. A playful exploration of volume and capacity featuring Native characters and a glossary of Cherokee words.

Tuesday, January 25, 2022

Analyzing a Worksheet: "Where Would You Fit In?"

If you scored between 21 and 32, you are ready to move to the New England Colonies! You'll fit right in with those Northerners.

If you scored between 11 and 20, you are right in the middle of the New England and the Southern Colonies. You belong in the Middle Colonies!

If you scored between 0 and 10, the South is the place to be for you. You would make the ideal Southern colonist.

I may be back to share more thoughts later. In the meantime, I welcome your thoughts on this worksheet. Has it or others with similar issues been given to your child? Or to children of your friends, or colleagues? And of course, get a copy of Social Studies for a Better World!

Monday, January 24, 2022

American Indian Library Association Announces its 2022 Youth Literature Awards

|

| Source: https://ailanet.org/2022-aila-youth-literature-awards-announcement/ |

For Immediate Release

January 24, 2022

AILA announces 2022 American Indian Youth Literature Awards

CHICAGO — Today American Indian Youth Literature Award winning titles were highlighted during the American Library Association (ALA) Youth Media Awards, the premier announcement of the best of the best in children’s and young adult literature.

Awarded biennially, the award identifies and honors the very best writings and illustrations for youth, by and about Native American and Indigenous peoples of North America. Works selected to receive the award, in picture book, middle grade, and young adult categories, present Native American and Indigenous North American peoples in the fullness of their humanity in present, past and future contexts.

The 2022 American Indian Youth Literature Award winner for best Picture Book is “Herizon,” written by Daniel W. Vandever (Diné), illustrated by Corey Begay (Diné), and published by South of Sunrise Creative. Herizon follows the journey of a Diné girl as she helps her grandmother retrieve a flock of sheep. Join her venture across land and water with the help of a magical scarf that will expand your imagination and transform what you thought possible. The inspiring story celebrates creativity and bravery, while promoting an inclusive future made possible through intergenerational strength and knowledge.

The committee selected five Picture Book Honor(s) titles including:

- “Diné Bich’eekę Yishłeeh (Diné Bizaad)/Becoming Miss Navajo (English),” written by Jolyana Begay-Kroupa (Diné), designed by Corey Begay (Diné), and published by Salina Bookshelf, Inc.

- “Classified: The Secret Career of Mary Gold Ross, Cherokee Aerospace Engineer,” written by Traci Sorell (Cherokee), illustrated by Natasha Donovan (Métis), and published by Millbrook Press.

- “Learning My Rights with Mousewoman,” written and illustrated by Morgan Asoyuf (Ts’msyen), and published by Native Northwest.

- “I Sang You Down From the Stars,” written by Tasha Spillet-Sumner (Cree and Trinidadian), illustrated by Michaela Goade (Tlingit & Haida), and published by Little, Brown Books for Young Readers, a division of Hachette Book Group.

- “We Are Still Here! Native American Truths Everyone Should Know,” written by Traci Sorell (Cherokee), illustrated by Frané Lessac, narrated by a cast of Cherokee, Navajo, Choctaw and Chickasaw Tribal representation, and published by Charlesbridge Publishing, Inc. / Live Oak Media.

The 2022 American Indian Youth Literature Award winner for best Middle Grade Book is “Healer of the Water Monster,” written by Brian Young (Diné), cover art by Shonto Begay (Diné), and published by Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers. When Nathan goes to visit his grandma, Nali, at her home on the Navajo reservation, he knows he’s in for a summer with no running water and no electricity. That’s okay, though. He loves spending time with Nali. One night, Nathan finds something extraordinary, a Holy Being from the Navajo Creation Story – a Water Monster- in need of help. With electric adventure and powerful love, Brian Young’s debut novel tells the tale of a seemingly ordinary boy who realizes he’s a hero at heart.

The committee selected five Middle School Book Honor(s) titles including:

- “Ella Cara Deloria: Dakota Language Protector,” written by Diane Wilson (Dakota), illustrated by Tashia Hart (Red Lake Anishinaabe), and published by Minnesota Humanities Center.

- “Indigenous Peoples’ Day,” written by Katrina M. Phillips (Red Cliff Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe), and published by Pebble, an imprint of Capstone.

- “Jo Jo Makoons: The Used-to-Be Best Friend,” written by Dawn Quigley (Turtle Mountain Band of Ojibwe), illustrated by Tara Audibert (Wolastoqey), and published by Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

- “Peggy Flanagan: Ogimaa Kwe, Lieutenant Governor,” written by Jessica Engelking (White Earth Band of Ojibwe), illustrated by Tashia Hart (Red Lake Anishinaabe), and published by Minnesota Humanities Center.

- “The Sea in Winter,” written by Christine Day (Upper Skagit), cover art by Michaela Goade (Tlingit and Haida), and published by Heartdrum, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers.

The American Indian Youth Literature Award for best Young Adult Book is “Apple (Skin to the Core),” written by Eric Gansworth (Onondaga), cover art by Filip Peraić, and published by Levine Querido. The term “Apple” is a slur in Native communities across the country. It’s for someone supposedly “red on the outside, white on the inside.” In Apple (Skin to the Core), Eric Gansworth tells his story, the story of his family, of Onondaga among Tuscaroras, of Native folks everywhere. Eric shatters that slur and reclaims it in verse and prose and imagery that truly lives up to the word heartbreaking.

The award committee selected five Young Adult Book Honor(s) including:

- “Elatsoe,” written by Darcie Little Badger (Lipan Apache Tribe), cover art and illustrations by Rovina Cai, and published by Levine Querido.

- “Firekeeper’s Daughter,” written by Angeline Boulley (Sault Ste. Marie Tribe of Chippewa Indians), cover art by Moses Lunham (Ojibway and Chippewa), and published by Henry Holt Books for Young Readers / Macmillan Children’s Publishing Group.

- “Hunting by Stars,” written by Cherie Dimaline (Metis Nation of Ontario), cover art by Stephen Flaude (Métis), and published by Amulet Books, an imprint of ABRAMS.

- “Notable Native People: 50 Indigenous Leaders, Dreamers, and Changemakers from Past and Present,” written by Adrienne Keene (Cherokee Nation), illustrated by Ciara Sana (Chamoru), and published by Ten Speed Press, an imprint of Penguin Random House.

- “Soldiers Unknown,” written by Chag Lowry (Yurok, Maidu and Achumawi), illustrated by Rahsan Ekedal, and published by Great Oak Press.

Members of the American Indian Youth Literature Award jury are AILA President Aaron LaFromboise, Blackfeet Nation, Browning, Montana; Chair Vanessa ‘Chacha’ Centeno, Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma, Sacramento, California; Co-Chair Anne Heidemann, Mount Pleasant, Michigan; Lara Aase, San Marcos, California; Catherine Anton Baty, Big Sandy Rancheria, Austin, Texas; Naomi Bishop, Akimel O’odham, Tucson, Arizona; Joy Bridwell, Chippewa Cree Tribe, Box Elder, Montana; Erin Hollingsworth, Utqiaġvik, Alaska; Janice Kowemy, Laguna Pueblo, New Mexico; Sunny Day Real Bird, Apsaalooke Crow Tribe, Billings, Montana; and Allison Waukau, Menominee and Navajo, Minneapolis, Minnesota.

The American Indian Library Association is a membership action group that addresses the library-related needs of American Indians and Alaska Natives. Members are individuals and institutions interested in the development of programs to improve library cultural and informational services in school, public, and academic libraries. AILA is committed to disseminating information about Indian cultures, languages, values, and traditions to the library community. https://ailanet.org/

Sunday, January 16, 2022

Highly Recommended: EVERYTHING YOU WANTED TO KNOW ABOUT INDIANS BUT WERE AFRAID TO ASK, YOUNG READERS EDITION

Young Readers' Edition

From the acclaimed Ojibwe author and professor Anton Treuer comes an essential book of questions and answers for Native and non-Native young readers alike. Ranging from “Why is there such a fuss about nonnative people wearing Indian costumes for Halloween?” to “Why is it called a ‘traditional Indian fry bread taco’?“ to “What’s it like for Natives who don’t look Native?” to “Why are Indians so often imagined rather than understood?”, and beyond, Everything You Wanted to Know About Indians But Were Afraid to Ask (Young Readers Edition) does exactly what its title says for young readers, in a style consistently thoughtful, personal, and engaging.

Tuesday, January 11, 2022

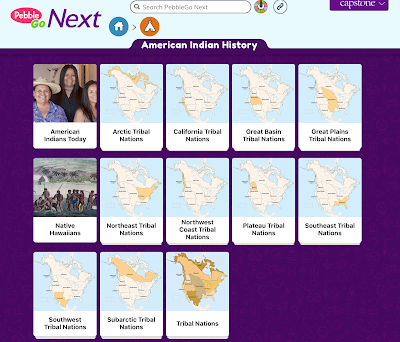

A Second Look at PebbleGo Next

The Hopi nation is made up of many different villages. Hopi people identify closely with their own village. Their own village is much more important to them than the Hopi nation as a whole."

Tuesday, January 04, 2022

Indigenous Nations in Nonfiction

Monday, January 03, 2022

Debbie Reese in THE WEEK, JUNIOR

On July 2, 2021, an interview of me was published in The Week, Junior. I was thrilled that they knew about AICL, and that they wanted to tell their readers about my work. In June, I think, I started getting notes from friends and colleagues who subscribe to it, sharing their delight in seeing me on one of the pages. It was a terrific high for me!

AICL has been around since 2006, pointing out bias and misrepresentation of Native peoples, and shining a bright light on excellent books by Native writers. A heartfelt kú'daa to those who read and share what we publish here on AICL.

Tuesday, December 28, 2021

Highly Recommended: THE FIRE by Thomas Peacock

Written by Thomas Peacock (Fond du Lac Band of Lake Superior Ojibwe)

Illustrations by Anna Granholm

Published by Black Bears & Blueberries

Published in 2021

Reviewer: Jean Mendoza

Review Status: Highly Recommended

This story is a fictionalized account of the Great Fire of 1918 based on an interview of Elizabeth (Betty) Gurno, a Fond du Lac Reservation elder. Betty was a little girl when the fire swept the area. The Fire of 1918 destroyed the city of Cloquet, Minnesota and surrounding communities, including the Fond du Lac Reservation, and resulted in the loss of many lives.

Author Thomas Peacock frames Betty's telling of the story within a later-day classroom scene in Minnesota. Betty has come to her grandchild's classroom to share her memories of the fire.

First reason to recommend The Fire: It focuses on Indigenous people's experience during a catastrophic event, and joins a fairly small pool of exciting and moving historical fiction picture books told from an Indigenous perspective. In The Fire, Ojibwe oral history is at the center. The author uses some words in Ojibwemowin and refers to Ojibwe traditions (such as offering asemaa, tobacco, to an elder who shares wisdom).

Second reason: It's timely. Wildland fires have affected communities around the country in recent years. Children are wondering how such fires can happen, how people survive them, and what happens afterward. Young readers may want to do further research about the Great Fire of 1918, using sources like the National Weather Service article and a dedicated page on the Library of Congress Web site.

Third reason: The illustrations amplify the storytelling. There's plenty of drama in the pictures. Burning boards fly through the air; dozens of animals join the people in the river as the fire rages. But there are also some important, more subtle touches. Look closely at the page that shows Betty's grandparents warning her family about the fire. The hazy trees and yellowish sky behind the horse and buggy aren't just meant to be pretty. That's the smoke, already drifting into Fond du Lac, a silent warning.

Fourth reason: The story manages to locate modest, honest hope and affirmation in the aftermath of the disaster. Readers learn that no Ojibwe people died, but "more than four hundred fifty of our non-Native neighbors were lost in the fire," and several non-Native towns burned to the ground. (For comparison, I checked the estimated death toll of the Chicago Fire of 1871 -- around 300.) Grandma Betty recounts that her grandmother's home escaped the fire, and she shared what food she had with other Fond du Lac families, most of whom had lost everything. I love the final words of Grandma Betty's storytelling: "We help each other. That is what we do." (It reminds me of the values behind Richard Van Camp's little board book, May We Have Enough to Share.)

I also love that when Betty ends her storytelling, the children line up to hug her. Maybe that's a classroom custom. But I think it also shows that the children are moved by this elder's story of the trauma she and their community endured, and they are caring for her in their way, years afterward.

The Fire is a valuable book to have on your shelves, and to share with children you know.

Monday, December 20, 2021

HIGHLY RECOMMENDED: THE SEA IN WINTER

By Christine Day (Upper Skagit)

Back in September 2020, Debbie blogged about her positive reaction to reading the ARC of Christine Day's second novel for young people -- The Sea in Winter. Since then, the book has gotten positive critical attention, including a Kirkus starred review and School Library Journal "Best Book". Here, finally, is my "short and sweet" AICL review.

The publisher, Heartdrum, says this about The Sea in Winter:

It’s been a hard year for Maisie Cannon, ever since she hurt her leg and could not keep up with her ballet training and auditions. Her blended family is loving and supportive, but Maisie knows that they just can’t understand how hopeless she feels.... Maisie is not excited for their family midwinter road trip along the coast, near the Makah community where her mother grew up. But soon, Maisie’s anxieties and dark moods start to hurt as much as the pain in her knee. How can she keep pretending to be strong when on the inside she feels as roiling and cold as the ocean?

Reason One to recommend The Sea in Winter: The sense of place.

The author writes from the heart when she describes the story's setting. It's good to have a book about a contemporary middle schooler, that celebrates geoduck clams and the removal of the Elwha River dam. It's set in much the same part of the continent as a certain popular vampire-and-werewolf series, but Day's storytelling is noticeably more attuned to the landforms, the weather, the animals, the sea.

Reason Two: Respect for advocacy and activism.

Advocacy for social and environmental justice, and for Indigenous rights, are natural parts of family life in Maisie's world. For example, readers learn that her family has been directly affected by treaty rights to harvest shellfish, and removal of dams that kept salmon from spawning in local rivers. And conflict around the 1999 Makah whale hunt (the tribe's first effort to hold its traditional hunt in 70 years) forced an important decision for some of Maisie's Makah relatives.

Reason Three: The protagonist's unique perspective.

The Sea in Winter offers the young reader a window on the experience of a child with an unusual level of ambition. Most children Maisie's age haven't discovered an activity that inspires the kind of commitment she has to ballet. What is it like, at age 12, to have your entire life, including peer friendships, revolve around ballet, because you love it that much? Who else understands such dedication? And how do you cope, at age 12, when you face the loss of your beautiful dream? Is that what depression feels like?

Reason Four: Maisie's solid, loving Native family.

Leo Tolstoy famously, or infamously, wrote, "All happy families are alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way." Though Maisie's family faces some challenges, including Maisie's depression, they are fundamentally "happy" together -- affectionate, thoughtful, supportive, respectful of boundaries, and knowledgeable about their Native identities. But they're by no means ordinary, stereotypical, or indistinguishable from other fictional families that are doing essentially okay. The author makes them interesting, not merely quirky or weird, as individuals and as a unit.

In short, I add my voice to the chorus of recommendations: Read and share The Sea in Winter with young people in your life!

Wednesday, December 01, 2021

AICL's Best Books of 2021

|

| A Sample of AICL's Best Books of 2021 |

Those who study and write about children's books will mark 2021 as a significant year because it is the year that Heartdrum (an imprint of HarperCollins) released several books written and illustrated by Native people. Heartdrum's first book, The Sea In Winter by Christine Day (enrolled, Upper Skagit), is outstanding. We read an advanced copy of it in 2020 and highly recommended it. You will find it below, along with several books we read from Heartdrum. What Heartdrum represents is important. Cynthia Leitich Smith (Muscogee Creek) brought it into existence. For all that she has done, she was named as the recipient of the 2021 NSK Neustadt Prize for Children's Literature. Three of her books were republished this year. In our articles, book chapters, and presentations, we usually include one or more of her books. We're pleased to see the new updated versions and you'll find them listed below.

Books Written or Illustrated by non-Native People

Tuesday, November 30, 2021

RECOMMENDED: NENABOOZHOO AND THE ELK'S HEAD

Nenaboozhoo is a prominent figure in the Anishinaabe traditional stories that have been published over the years. He appears in several picture books published in the past couple of years. I hope to review all of them eventually, but today I'm taking a "short and sweet" look at just one: Nenaboozhoo and the Elks's Head/Nenaboozhoo miinawaa Adik Odishtigwaan.

Here's my quick summary of the story:

Nenaboozhoo tricks an elk into lending him a beautiful bow and arrow, and then kills the elk for food. The trees that witness this treachery let their displeasure be known, but Nenaboozhoo is quite pleased with himself. Before long, though, he gets his comeuppance, as he often does, showing listeners how NOT to act.

I'd recommend this story for upper elementary age children, and older.

First reason to recommend this book: Native people are involved at all levels of its publication. It's an Ojibwe traditional story retold in a collaboration between Dr. Giniwgiishig (a school principal) and Niizhobines, an Ojibwe elder and storyteller. It's bilingual, in English and Ojibwemowin. And the publisher is the Native-owned non-profit Black Bears and Blueberries.

Second reason: The book has a mission. Initially the story was part of the Indian Education Curriculum for Red Lake (MN) School District #38. The front matter includes this dedication:

This endeavor is for our children so that they will know who they are and where they come from and to learn our language so they will be strong and proud that they are Anishinaabe and stand up and lead and succeed.

There's another statement in the front matter of this book and several of the others mentioned under my Reason 4, below: "The stories in these books are told only when snow is on the ground and a tobacco offering is made." This tells the reader that even though this story and others like it are engaging, the sharing of them is important enough that there's a protocol for doing so. They were never intended just for amusement.

Third reason: Kids who aren't Anishinaabe can engage with and learn from the book, too. Just seeing Ojibwemowin in print can affirm for them that specific Indigenous languages exist and have value -- Native people don't just "talk Indian". Like many traditional stories, this one is an opportunity for considering how to treat others, and how a person's self-centered actions can have uncomfortable consequences.

Fourth reason to recommend Nenaboozhoo and the Elk's Head: It's just one of several bilingual English-Ojibwemowin books published by Black Bears and Blueberries that belong in classroom libraries. They include:

- by Dr. Giniwgiishig and Niizhobines -- Why the Bear Has a Short Tail; How the Boy and the Rabbit Helped Each Other; Nenaboozhoo Steals Fire; and When the Boy Was Made into a Whirlwind.

- by Liz Granholm -- Rabbit and Otter; Rabbit and Otter go Sugarbushing

- by Tara Perron -- Animals of Nimaamaa-Aki (Dakota version is Animals of Kheya Wita)

You can find out more about the bilingual books put out by Black Bears and Blueberries on their Web site.

Highly Recommended: ON THE TRAPLINE by David A. Robertson and Julie Flett

Ininimowin means "Cree language."

Monday, November 29, 2021

Highly Recommended! CLASSIFIED:THE SECRET CAREER OF MARY GOLDA ROSS, CHEROKEE AEROSPACE ENGINEER, by Traci Sorell and Natasha Donovan

Sunday, November 28, 2021

Highly Recommended: THE OTHER TALK: RECKONING WITH OUR WHITE PRIVILEGE by Brendan Kiely

The facilitators were about to move on to their next exercise when a Native American woman in the audience stood up. She wanted to know why the racetrack model, why the entire workshop, did not include or allude to, in any way, Indigenous people in the United States. "This," she went on to explain, "is the kind of erasure we face every day."