- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materials about American Indians

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

- Debbie on Social Media

- 2024 American Indian Literature Award Medal Acceptance Speeches

- Native Removals in 2025 by US Government

Tuesday, November 19, 2019

Recommended: The Case of the Missing Auntie

How often have you read a middle grade mystery novel that had you in tears just a few pages after making you laugh? That's what happened when I spent yesterday with an ARC of Michael Hutchinson's new Mighty Muskrats Mystery, The Case of the Missing Auntie (Second Story Press, 2019).

In The Case of Windy Lake, Hutchinson introduced four mystery-solving Cree cousins: Atim, Chickadee, Samuel, and Otter, known in their community as the Mighty Muskrats. Now he has the Muskrats head for the Big City to visit some more cousins, and to attend a big event called the Exhibition Fair. Hutchinson reveals a bit more about each character this time, along with a lot more about historical and contemporary Indigenous experience in the part of the world currently known as Canada.

Chickadee looks forward to the Exhibition (the Ex), but she's also on a mission. Their Grandpa has told her about his younger sister who was taken from a boarding school decades ago, and lost in "The Scoop" The family hasn't seen or heard from her since, and he wants very much to find her. "The Scoop" is the informal name for a set of Canadian policies that resulted in many First Nations children disappearing, forever separated from their families. Chickadee is determined to find out what happened to Auntie Charlotte, even if that means she has to guilt-trip her cousins into helping her. And even if she has to navigate the city transit system alone while Atim, Samuel, and Otter try to find a ticket for Otter to a sold-out concert by their favorite Indigenous band.

Hutchinson's storytelling is engaging. The kids find some good allies and face some unexpected challenges, even dangers. To say more about the plot lines might give something away. So.

Windy Lake featured some standout prose, and Hutchinson's way with words is evident in Missing Auntie as well. Here are a couple of examples.

a) Chickadee and her older cousin Harold are talking at breakfast about the contrasts between the Windy Lake reserve and the city. Harold says, "City people don't seem to know there is a different life out there. It's like the city mouse killed the country mouse and forgot he ever existed. Our people can get lost in the city." That sly reference to one of Aesop's fables made me smile and think, "Funny!" and "Yikes!" at the same time.

b) And here's part of the description of an arcade and pool hall the Muskrats enter during their effort to get that concert ticket for Otter: "The Crystal Palace was a mixture of deep shadows, colorful neon, and arcade lights. It smelled like the ghosts of greasy burgers and spilled pop....A palisade of pool sticks lined the outside walls. A scattering of players focused on their games. The smack and click of pool balls colliding kept a random tempo."

But you don't get the impression that Hutchinson is bashing urban life -- the Muskrats meet some good people, people of subtle courage and outright heroism, along with racists, criminals, and people who have lost themselves. It's clear that the city can be a combination of the strange, the unfriendly, the wondrous, and the ordinary. And the characters of the Muskrats are developing, too, in ways that are easy to appreciate. These are good-hearted, caring, smart young people, but they're all individuals.

Hutchinson also weaves in factual information as the kids sort out what happened to their Grandpa's little sister. Occasionally that can seem like a lot of exposition, but some readers won't know otherwise about the boarding schools and the Scoop, about present-day bureaucracy, about Canada's Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and about how the old racist policies continue to affect First Nations families today.

I found the ending to be realistic and satisfying, even though it unfolded in a way I didn't expect. Overall, Missing Auntie is a good read, with an emotional "punch," and I can hardly wait for the Mighty Muskrats to take their next case. But Missing Auntie won't be out until spring 2020. Preorder your copy now from Second Story Press!

Recommended! THE RELUCTANT STORYTELLER by Art Coulson; illustrated by Hvresse Christie Blair Tiger

Note from Debbie on Nov 28, 2023: Due to my concerns over Art Coulson's claim of being Cherokee, I am no longer recommending his books.

But!

Don't look away! Benchmark Education offers books that I know--without a doubt--that Native children will be happy to read! One of my favorite books--ever--is Where'd You Get Your Moccasins by Bernelda Wheeler. When I was teaching children's literature way back in grad school in the 1990s, it was on the required list of books I asked pre-service teachers to buy. Some would look at the stapled spine and think less of it without reading the words in the book that made, and makes, my heart soar! They had to learn to set aside elite notions of what a book should be like, and think about the content and what that content could do for readers in their classrooms.

I ask that same thing for The Reluctant Storyteller. The things I look for in a book are all here. It is set in the present day, it is tribally specific, it is written and illustrated by Native people, and it rings true! Coulson knows what he's talking about. The family at the heart of this story is filled with storytellers who adore being out and about, telling Native stories. They're from Oklahoma, but live in the Twin Cities. They do visit, a lot, and a trip is coming up. Chooch, the main character in Coulson's book doesn't want to go. He's rather stay in Minneapolis for the Lacrosse tournament.

Chooch doesn't tell stories and can't imagine himself as a storyteller. His dream? To be a chef. But, nobody knows that he wants to be a chef. He enjoys cooking with his mom and grandma, making up recipes. Things he makes are tasty!

On the way to their Oklahoma, Chooch's uncle tells him a story about a Tsula, a fox who wishes he had a coat of feathers, like Totsuhwa, the redbird that he sees flying about in the trees, so that he could fly, too. One day he runs and runs and runs, so fast, that his feet are off the ground. Day moves into night and, well, he started flying. He's no longer Tsula, the fox. Now, he's Tlameha, the bat. People who read AICL regularly know that I'm careful about traditional stories and how a writer works with them, uses them, bringing them into a book. This story is one that the Cherokee people tell. Coulson is Cherokee. I trust that he's sharing a story that can be shared. And--I love the way he brought it to Chooch.

They get to Oklahoma, and Chooch is drawn to the cooking area of a Native gathering. By the time we get to the final pages of The Reluctant Storyteller, Chooch understands himself in ways he did not before the trip. He's learned that there are many ways to be storytellers.

And, there are many ways to tell stories--to bring stories to children and teens! That's what I mean, up top, where I say there's a specialness to this book. There's layers of truth in it. Layers of Native life, too...

So, don't turn away from leveled readers. If you open the Benchmark catalog, you'll see other writers there, too. Like Ibi Zoboi! And David Bowles! And Jane Yolen! Jerry Craft, and, Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve! These are names teachers and librarians are familiar with. Look at the catalog! You'll see others, too.

I like The Reluctant Storyteller very much and recommend that you get it... but I think the books are hard to get. I got my copy from Art Coulson's website.

Recommended: JOHNNY'S PHEASANT written by Cheryl Minnema, pictures by Julie Flett

Johnny's Pheasant is written by Cheryl Minnema (Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe) and illustrated by Julie Flett (Cree-Métis). New in 2019, it is a picture book I am pleased to recommend.

Grandma's are special, aren't they? Mine was, and I know my mom is special to my daughter and all her other grandchildren. In some families, grandma's make things. When I was a kid, I hung out with my grandma, a lot. I have such fond memories of those times, helping and watching her make things.

Back in the 1960s when the US government was putting a blacktop road on our reservation, they also strung barbed wire fencing to keep livestock off the road. That barbed wire came on wire spools that are about the size of a 5 gallon bucket. The end parts of the spool looked like flower petals. Here's a photo that sort of looks like what I have in my memory:

I walked with my grandmother for miles and miles, gathering up empty, cast off spools. At home, she bound them together in an array that she attached to a wood frame. These then became charming gates to the porch, and to the garden. She also worked with feathers. She especially liked peacock feathers. She'd trim them and attach them to fabric wall hangings. They were so pretty!

In Johnny's Pheasant, we see a grandma and grandson, out and about. Johnny spies something in the grass. Turns out, it is a pheasant! Grandma thinks it is dead and that she can use its feathers in her craft work. But Johnny thinks the pheasant is ok. He's right!

The pheasant comes to from its seemingly-dead state, and flies about the house, at one point, landing on Grandma's head! Johnny thinks the pheasant, lying there in Grandma's house, had heard his grandma say she was going to use its feathers--and her words roused it!

From grandma's head, the pheasant flies out the open door. Johnny and his grandma go outside and watch it fly away. But, a single feather flutters to the ground. When Johnny hands it to his grandma, she exclaims "Howah."

Howah is an Ojibwe expression meaning 'oh my!' I enjoyed reading this story, but when I read "Howah," I paused. Ojibwe kids are gonna love that! Johnny's Pheasant is a delight on many levels. Published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2019, I recommend it for every family, Native or not, who tells stories about grandma's. Its quite a heartwarming story!

Back in the 1960s when the US government was putting a blacktop road on our reservation, they also strung barbed wire fencing to keep livestock off the road. That barbed wire came on wire spools that are about the size of a 5 gallon bucket. The end parts of the spool looked like flower petals. Here's a photo that sort of looks like what I have in my memory:

I walked with my grandmother for miles and miles, gathering up empty, cast off spools. At home, she bound them together in an array that she attached to a wood frame. These then became charming gates to the porch, and to the garden. She also worked with feathers. She especially liked peacock feathers. She'd trim them and attach them to fabric wall hangings. They were so pretty!

In Johnny's Pheasant, we see a grandma and grandson, out and about. Johnny spies something in the grass. Turns out, it is a pheasant! Grandma thinks it is dead and that she can use its feathers in her craft work. But Johnny thinks the pheasant is ok. He's right!

The pheasant comes to from its seemingly-dead state, and flies about the house, at one point, landing on Grandma's head! Johnny thinks the pheasant, lying there in Grandma's house, had heard his grandma say she was going to use its feathers--and her words roused it!

From grandma's head, the pheasant flies out the open door. Johnny and his grandma go outside and watch it fly away. But, a single feather flutters to the ground. When Johnny hands it to his grandma, she exclaims "Howah."

Howah is an Ojibwe expression meaning 'oh my!' I enjoyed reading this story, but when I read "Howah," I paused. Ojibwe kids are gonna love that! Johnny's Pheasant is a delight on many levels. Published by the University of Minnesota Press in 2019, I recommend it for every family, Native or not, who tells stories about grandma's. Its quite a heartwarming story!

Sunday, November 17, 2019

Dear _____: I got your letter about Thanksgiving

Today's blog post has an unusual title. It is my effort to reply, in one response, to the range of queries I get by email. These are emails that give me hope. They embody a growing understanding that Thanksgiving, as observed in the U.S., is fraught with problems.

Those problems range from the stereotyping of Native peoples to the pretense that peoples in conflict had a merry sit-down dinner.

Some emails are from parents who are dismayed when they visit their library and see children's books filled with those stereotypes and pretenses. These parents want their children to learn the truth. So they turn to the library for help.

Some parents tell me that, in a previous year, they had talked with librarians about the problems in the books. These parents felt hopeful that the librarians understood and would provide different kinds of programming and displays this year but that doesn't happen. Others tell me that the librarian interprets their questions as efforts to censor books. Some get lectured about censorship.

The thrust of the emails is this: what can I do?

Those of you who are writing to me have already taken the first step, which is to know there's a problem. Others have to know that, too. In order for changes to happen, more people have to understand what you already know. There is a problem. So, talking with friends and colleagues about it is a second step. Some of you already do that, which is great. Keep talking! And use social media! Though there are valid concerns about the merits of social media, I think it is why so many towns, cities, universities, schools, and states have instituted Indigenous Peoples' Day instead of Columbus Day.

With that in mind, I'm sharing a terrific resource that is available, online, at no cost.

Titled "Origin Narrative: Thanksgiving," it is a free teacher's guide to be used by people who have bought a copy of An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States for Young People but I think people can use it without the book.

A brief note: In 2014, Dr. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States was released by Beacon Press. Teachers asked for a version that they could use with teens. Beacon asked if I would do it; I invited my friend and colleague, Dr. Jean Mendoza, to do it with me, and it was released in 2019, with "For Young People" as part of its title.

Here's a screen capture of the lesson plan. To download it, go to Beacon's website where you can see the webpage of it and the link to download a pdf. You can ask your library to get the book, and if you have the option, see if you can schedule one of the library's meeting rooms to have a conversation with others about the holiday.

I welcome other thoughts. What strategies have you used that seemed to help?

Ah! Meant to include a bit more. Some people write to me asking for Thanksgiving books that I recommend they use with children. My impulse is to offer some suggestions, but I am also trying to remind them and myself that the question is, in essence, one that centers the holiday itself. It seems to recognize that stereotyped and erroneous storylines are not ok, but it still wants Native peoples at that table.

Instead of providing a list of books that can be used for this week, I am asking that you use books by Native writers, all year long. Don't limit our existence to this holiday.

In the Best Books page here at AICL, you'll find lists that I create, and links to the pages about the Youth Literature Awards, given by the American Indian Library Association. I've also written several articles that are available online. Some are about books I recommend, and some are ones that invite you to think critically about books. Here's the links. They work right now but journals don't keep articles available this way, long term. You might have to ask your librarian for the article if a link no longer works.

Those problems range from the stereotyping of Native peoples to the pretense that peoples in conflict had a merry sit-down dinner.

Some emails are from parents who are dismayed when they visit their library and see children's books filled with those stereotypes and pretenses. These parents want their children to learn the truth. So they turn to the library for help.

Some parents tell me that, in a previous year, they had talked with librarians about the problems in the books. These parents felt hopeful that the librarians understood and would provide different kinds of programming and displays this year but that doesn't happen. Others tell me that the librarian interprets their questions as efforts to censor books. Some get lectured about censorship.

The thrust of the emails is this: what can I do?

Those of you who are writing to me have already taken the first step, which is to know there's a problem. Others have to know that, too. In order for changes to happen, more people have to understand what you already know. There is a problem. So, talking with friends and colleagues about it is a second step. Some of you already do that, which is great. Keep talking! And use social media! Though there are valid concerns about the merits of social media, I think it is why so many towns, cities, universities, schools, and states have instituted Indigenous Peoples' Day instead of Columbus Day.

With that in mind, I'm sharing a terrific resource that is available, online, at no cost.

A brief note: In 2014, Dr. Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States was released by Beacon Press. Teachers asked for a version that they could use with teens. Beacon asked if I would do it; I invited my friend and colleague, Dr. Jean Mendoza, to do it with me, and it was released in 2019, with "For Young People" as part of its title.

Here's a screen capture of the lesson plan. To download it, go to Beacon's website where you can see the webpage of it and the link to download a pdf. You can ask your library to get the book, and if you have the option, see if you can schedule one of the library's meeting rooms to have a conversation with others about the holiday.

I welcome other thoughts. What strategies have you used that seemed to help?

****

Ah! Meant to include a bit more. Some people write to me asking for Thanksgiving books that I recommend they use with children. My impulse is to offer some suggestions, but I am also trying to remind them and myself that the question is, in essence, one that centers the holiday itself. It seems to recognize that stereotyped and erroneous storylines are not ok, but it still wants Native peoples at that table.

Instead of providing a list of books that can be used for this week, I am asking that you use books by Native writers, all year long. Don't limit our existence to this holiday.

In the Best Books page here at AICL, you'll find lists that I create, and links to the pages about the Youth Literature Awards, given by the American Indian Library Association. I've also written several articles that are available online. Some are about books I recommend, and some are ones that invite you to think critically about books. Here's the links. They work right now but journals don't keep articles available this way, long term. You might have to ask your librarian for the article if a link no longer works.

- Native Stories: Books for tweens and teens by and about Indigenous peoples, by Kara Stewart and Debbie Reese, at School Library Journal on August 20, 2019.

- "We Are Still Here": An Interview with Debbie Reese in English Journal, in 2016.

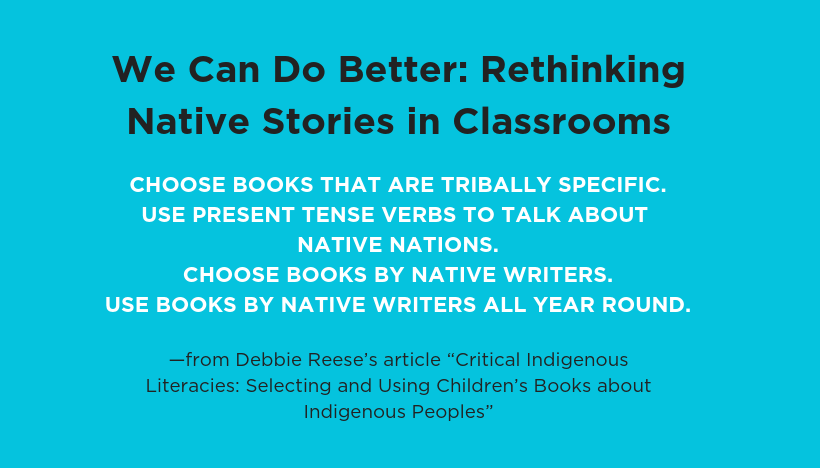

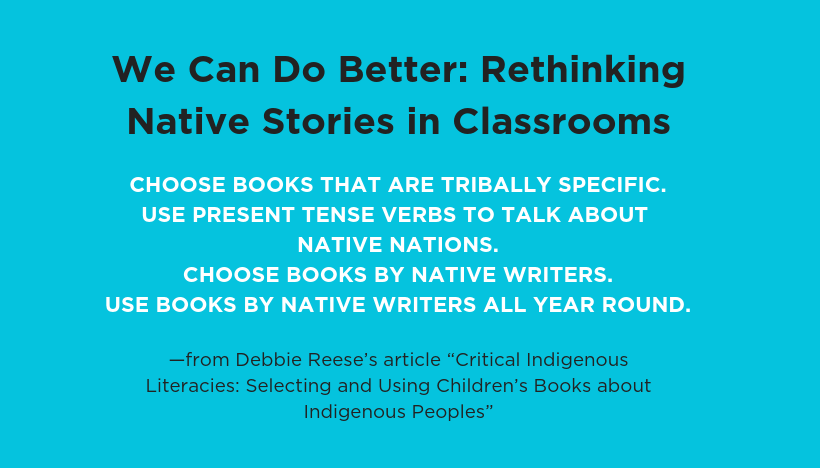

- Critical Indigenous Literacies: Selecting and Using Children's Books about Indigenous Peoples, by Debbie Reese in Volume 92, Number 6 of Language Arts (published in 2018).

- Twelve Picture Books that Showcase Native Voices by Debbie Reese in School Library Journal in 2018.

Friday, November 15, 2019

Recommended! STRANGELANDS written by Magdalene Visaggio and Darcie Little Badger; art by Guillermo Sanna; Cover by Dan Panosian

Native teens! Go to the Humanoids site and get copies of the comic series, Strangelands. They're written by Magdalene Visaggio and Darcie Little Badger. The art is by Guillermo Sanna, and Dan Panosian did the cover.

I've read the first three...

.... and definitely recommend that you add them to your comic and graphic novel collection.

Here's info about the series:

Right now in the series they're at a lodge in Colorado where they can rid themselves of these powers. Adam doesn't like the decor of the "Wild Saints" lodge. In this passage, he's glaring at a dreamcatcher, and says:

And of course, get this new series, Strangelands.

I've read the first three...

.... and definitely recommend that you add them to your comic and graphic novel collection.

Here's info about the series:

Two strangers find themselves inextricably tied together by inexplicable superpowers. Fighting their connection could mean destroying the world.

Opposites attract? Elakshi and Adam Land aren’t married. In fact, a month ago, they were perfect strangers, dwelling in lands foreign to one another. But now, they’re forced to remain by one another’s side, for their separation could mean the planet’s demise. Their greatest challenge is to stay together — even if they have to tear the world apart to do so.See that? Elakshi and Adam's last name is Land. A hint, maybe, about who they are and how and why they have the powers they have--and don't want? I'm intrigued!

Right now in the series they're at a lodge in Colorado where they can rid themselves of these powers. Adam doesn't like the decor of the "Wild Saints" lodge. In this passage, he's glaring at a dreamcatcher, and says:

... all this Indian kitsch brings back terrible memories of paper teepees and chicken feather headdresses. Trust me. You do not want to be the only Apache kid at summer camp.From that passage, we know that Adam is Apache. One of the writers, Darcy Little Badger, is Lipan Apache. I think the first writing of hers that I read was in 2016 when I read "Né le," her space travel story in Love Beyond Body, Space and Time. (If you don't have that book, get it!).

And of course, get this new series, Strangelands.

Thursday, November 07, 2019

Not Recommended: SQUANTO'S JOURNEY: THE STORY OF THE FIRST THANKSGIVING

One of the questions I (Debbie) get around this time of the year is whether or not I recommend Joseph Bruchac's picture book, Squanto's Journey: The Story of the First Thanksgiving. The book was published in 2000 by Harcourt Brace. Illustrations are by Greg Shed.

I do not recommend Squanto's Journey because I view it as a feel-good story that is a lot like other books about Thanksgiving. This line is one example:

"Perhaps these men can share our land as friends."See the red question mark on the book cover? I'm using that today to pose some questions. In Squanto's Journey, Bruchac speaks as if he is Squanto. The first sentence in the book is:

My story is both strange and true.See? First person. As far as I've been able to determine, there are no records of anything that Squanto said to anyone. I'm going to keep looking, and if you find something, let me know.

My general position about creating speech and thoughts for a person who actually lived, hundreds of years ago, is that it is not appropriate. I usually say--for example--that a white woman imagining what a Native man said and thought hundreds of years ago is making huge leaps from her own existence to that Native man's time, place, culture, and language. If there are no written records to draw from, I think it ought not be done. To me, it doesn't matter if the work being created is fiction. If it is a person who actually lived, and for whom there are records a writer can draw from to quote the writings or speech of that person, then, ok. I think that can work. But otherwise, no. (The exception I make is when the book in question is written by someone of the subject's own nation who can draw from stories they tell about that person.)

So, a question: are there any documents or writings that quote the man we know as Squanto (more on that in a moment)?

Towards the end of the first paragraph, the text reads:

My name is Squanto.Though many people call him that, other sources say his name was Tisquantum and that "Squanto" was more like a nickname.

So, another question: What did that man actually say his name was?

I have more questions about the history told in Bruchac's book, but for now want to look at Squanto (Bruchac) learning that his wife, children, parents, and others who were close to him had died. Squanto says he will speak to them again when he walks on the "Road of Stars" to greet them. In the glossary, Bruchac says:

Road of Stars: The Milky Way, which is seen as a trail to reach the afterlife walked by those who have died.Is there evidence that Squanto and his people used that phrase? Regular readers of AICL know that I'm critical of white folks who make up things like that... I wonder what Bruchac's source for that is?

Update: a reader replied right away, saying "Isn't Bruchac Abenaki? This sounds like you're saying he's white." My answer: for most of the time that I've been studying children's books, I understood that Bruchac is Abenaki. More recently, he has said he is "Nulhegen Abenaki" which is a state recognized tribal nation. And even more recently, I have been reading Dr. Darryl Leroux's research that calls into question claims made to Métis identity/nationhood and, relevant to Bruchac, the four Abenaki tribes that the state of Vermont has recognized (Nulhegan Abenaki is in Vermont). So, I am not saying Bruchac is White, but I've definitely got questions about the Nulhegan Abenaki, now, given the research Leroux has done. Get his book, Distorted Descent: White Claims to Indigenous Identity" and see what you think. Respected Native scholars are sharing and recommending his book. I know that the responses to this update will be intense. Some will question my reference to Leroux's work. Some will be indignant that I am citing it, but I think it is important work that has bearing on my own work in children's literature.On another page, Squanto (Bruchac) uses the word "sachem." That word, as defined in the glossary, is supposed to mean "a leader of the people." Is that the word that Squanto would have used? What are the roots of that word?

Those are a few questions, for now. I might be back when I have more time, with additional questions (and maybe some answers). They're examples of the kinds of questions that I want teachers to ask when they read children's books, and to teach students to ask, too.

Wednesday, October 23, 2019

Thoughts on Patricia MacLachlan's THE HUNDRED-YEAR BARN (and my conclusion: Not Recommended)

On October 8, 2019, a reader wrote to ask me if I had seen Patricia MacLaughlan's The Hundred-Year Barn. Published by HarperCollins and illustrated by Kenard Pak, it came out recently.

Though the reader did not say why they were asking me about The Hundred-Year Barn, my hunch is that they read my article, An Indigenous Critique of Whiteness in Children's Literature (write to me and I'll send you a copy of it). The article is a published account of the remarks I made when I gave the 2019 May Hill Arbuthnot Lecture in Madison, WI.

In that lecture, I talked about the 2018 Caldecott Award winner, Hello Lighthouse (by Sophie Blackall) which I view as the epitome of Whiteness and the embodiment of the nostalgia we hear when we read the news ("Make America Great Again"). I said:

People did not (and do not) like me saying that about Blackall's book. That is, however, my sincere appraisal of it and my questions are sincere, too. What if we did think about the land every time we pick up a children's book like The Hundred-Year Barn?

Here's the description of The Hundred-Year Barn from the HarperCollins website:

The barn was built in 1919. We aren't told where (geographically), but Lachlan's dedication to her grandparents suggests that she may have had North Dakota prairies in mind when she wrote this story. But, she was born in Wyoming and said that she carries a bag of prairie dirt with her, so it could be Wyoming rather than North Dakota. What was going on in those states in the early 1900s? North Dakota became a state of the US in 1889. Wyoming became a state in 1890.

I'll say this, just to be obvious: all that land belonged to Native Nations.

I wanted to read The Hundred-Year Barn to see if there was any mention of Native people. I wondered if there was an author's note that said a bit more about that land, that barn, that family. In short: no. I've got the book in front of me today and it is simply a white family and community. Not a single mention of Native people or communities. Its history starts in 1919 with a white family.

Now--I know some of you are saying "MacLachlan's book isn't about Native people!" and "Don't judge it for what it doesn't have in it." But those are thin arguments, aren't they? If we think back to children's books that, for decades, showed women in narrow ways, critics asked questions, right? Asking questions about the contents of books is one mechanism to drive change.

I'm pretty sure that, in 1919, Native people were watching White people building barns on what was once Native homeland. And that, in that hundred-year period, Native people watched more and more White people move on to Native homelands and build things.

I'd bet, as a matter of face, that there were lawsuits in federal courts, through which Native Nations were trying to get the US to honor treaties it made with them.

The Hundred-Year Barn is--to some--a lovely story. To a Native person--to me--it is one like so many others that erase Native people from existence. It denies truths to children. And it feeds a nostalgia for a time that never really was like what you see when you read MacLachlan's book. The Hundred-Year Barn is not a good that I would recommend, to anyone. All kids deserve better than that.

Though the reader did not say why they were asking me about The Hundred-Year Barn, my hunch is that they read my article, An Indigenous Critique of Whiteness in Children's Literature (write to me and I'll send you a copy of it). The article is a published account of the remarks I made when I gave the 2019 May Hill Arbuthnot Lecture in Madison, WI.

In that lecture, I talked about the 2018 Caldecott Award winner, Hello Lighthouse (by Sophie Blackall) which I view as the epitome of Whiteness and the embodiment of the nostalgia we hear when we read the news ("Make America Great Again"). I said:

I have no doubt that people think books like Hello Lighthouse are "neutral" or "apolitical." That's Whiteness at work. From my perspective, the politics in Hello Lighthouse are front and center. Its nostalgia for times past is palpable. In Blackall's book, the life of a white family is affirmed and the lighthouse that they live in is on what used to be Native lands. There's no neutrality there. In fact, if we think about it, every children's book for which the setting is this continent, is set on what used to be Native lands. If we could all hold that fact front and center every time we pick up a children's book set on this continent, how might that change how we view children's literature? How might that shape the literature as we move into the future?

People did not (and do not) like me saying that about Blackall's book. That is, however, my sincere appraisal of it and my questions are sincere, too. What if we did think about the land every time we pick up a children's book like The Hundred-Year Barn?

Here's the description of The Hundred-Year Barn from the HarperCollins website:

One hundred years ago, a little boy watched his family and community come together to build a grand red barn. This barn become his refuge and home—a place to play with friends and farm animals alike.

As seasons passed, the barn weathered many storms. The boy left and returned a young man, to help on the farm and to care for the barn again. The barn has stood for one hundred years, and it will stand for a hundred more: a symbol of peace, stability, caring and community.

In this joyful celebration generations of family and their tender connection to the barn, Newbery Medal–winning author Patricia MacLachlan and award-winning artist Kenard Pak spin a tender and timeless story about the simple moments that make up a lifetime.

This beautiful picture book is perfect for young children who are curious about history and farm life.

The barn was built in 1919. We aren't told where (geographically), but Lachlan's dedication to her grandparents suggests that she may have had North Dakota prairies in mind when she wrote this story. But, she was born in Wyoming and said that she carries a bag of prairie dirt with her, so it could be Wyoming rather than North Dakota. What was going on in those states in the early 1900s? North Dakota became a state of the US in 1889. Wyoming became a state in 1890.

I'll say this, just to be obvious: all that land belonged to Native Nations.

I wanted to read The Hundred-Year Barn to see if there was any mention of Native people. I wondered if there was an author's note that said a bit more about that land, that barn, that family. In short: no. I've got the book in front of me today and it is simply a white family and community. Not a single mention of Native people or communities. Its history starts in 1919 with a white family.

Now--I know some of you are saying "MacLachlan's book isn't about Native people!" and "Don't judge it for what it doesn't have in it." But those are thin arguments, aren't they? If we think back to children's books that, for decades, showed women in narrow ways, critics asked questions, right? Asking questions about the contents of books is one mechanism to drive change.

I'm pretty sure that, in 1919, Native people were watching White people building barns on what was once Native homeland. And that, in that hundred-year period, Native people watched more and more White people move on to Native homelands and build things.

I'd bet, as a matter of face, that there were lawsuits in federal courts, through which Native Nations were trying to get the US to honor treaties it made with them.

The Hundred-Year Barn is--to some--a lovely story. To a Native person--to me--it is one like so many others that erase Native people from existence. It denies truths to children. And it feeds a nostalgia for a time that never really was like what you see when you read MacLachlan's book. The Hundred-Year Barn is not a good that I would recommend, to anyone. All kids deserve better than that.

Tuesday, October 22, 2019

Highly Recommended: FRY BREAD: A NATIVE AMERICAN FAMILY STORY

Update from Debbie, Oct 26, 2019: Unfortunately, the endpapers include some state recognized groups (I won't call them tribes or nations) whose website information makes me cringe. I hope the team who put the endpapers for Fry Bread together can make edits immediately. I am in the process of looking at them carefully and am considering creating a post that tells you how/why I am saying I would not personally call them tribes or nations.

All across social media, friends and colleagues are saying "Happy Book Birthday!" to Kevin Maillard and Juana Martinez-Neal. That's because their book, Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story is officially available, today, October 22, 2019.

There's a lot inside the covers of Fry Bread! What you find when you turn the pages is why I highly recommend it.

I wish I had slick video and video-editing skills so I could offer you a short and compelling film about the book. I don't have those skills, so... here's what I have:

Here's a screen capture (from my kindle copy of the book) of the last page I showed you in the video:

See those adults pointing out names of Native Nations? That's so wonderful! Mine--Nambé--is there, too. Here's my finger, pointing to it:

Those of you who follow AICL know that we emphasize the importance of sovereignty... Of knowing that Native Nations pre-date the United States. So many names inside this book! It will be empowering to so many readers!

There's more, though, to say about Fry Bread.

A few weeks ago, I gave a talk at the Santa Fe Indian Center, in Santa Fe, NM. I talked about the names of nations but I also talked about the range of hair color and skin tone in the book. See?

After the lecture, a family approached me to say how deeply moved they are by seeing a child with lighter skin and hair. Fry Bread pushes back on the expectation that Native people look the same (black hair, dark skin, high cheekbones etc.). That expectation means that adults don't hesitate to tell a Native child like the girl holding the cat that they are "not really an Indian" (or some variant of that phrase). That's such a damaging statement! When you hear an adult say that to anybody--but especially a child--stop them.

The final pages of Fry Bread can help you interrupt that kind of harmful statement. There, Maillard wrote that:

Update: October 23, 2019

In a comment, I was asked if the book has information about the history of fry bread and its impact on health of Native people. It does--and that is yet another aspect of what makes this book stand out.

One double paged spread shows Native people in shadow. The woman on the cover is telling kids about the long walk. The text is:

Fry bread is history

The long walk, the stolen land

Strangers in our own world

With unknown food

We made new recipes

From what we had

In the Author's Note, Maillard provides teachers and parents and librarians who do not know this history, with information they can use to prepare to use the book with kids. It is an exquisite author's note! It spans eight pages that correspond with the illustrated pages that are the heart of Fry Bread. And--they're footnoted! I don't recall seeing footnotes in an Author's Note before.

Maillard writes that people think the Navajo (Diné) were the first to make fry bread. He talks about how, across the country, Native people and our ways are resilient and here, today, in spite of efforts to weaken and destroy our nations and communities.

He writes that there are some Natives who are pushing back on the making and eating of fry bread. He wrote:

As noted above, the Author's Note is exquisite for the depth of information it provides. I quoted that one sentence, but will also note that the sentence has a footnote! It goes to Devon Mihesuah's article, "Indigenous Health Initiatives, Frybread, and the Marketing of Nontraditional 'Traditional' American Indian Foods." In his Author's Note, Maillard provides 15 footnotes! Like I said... exquisite. And--I think--groundbreaking.

All across social media, friends and colleagues are saying "Happy Book Birthday!" to Kevin Maillard and Juana Martinez-Neal. That's because their book, Fry Bread: A Native American Family Story is officially available, today, October 22, 2019.

There's a lot inside the covers of Fry Bread! What you find when you turn the pages is why I highly recommend it.

I wish I had slick video and video-editing skills so I could offer you a short and compelling film about the book. I don't have those skills, so... here's what I have:

Here's a screen capture (from my kindle copy of the book) of the last page I showed you in the video:

See those adults pointing out names of Native Nations? That's so wonderful! Mine--Nambé--is there, too. Here's my finger, pointing to it:

Those of you who follow AICL know that we emphasize the importance of sovereignty... Of knowing that Native Nations pre-date the United States. So many names inside this book! It will be empowering to so many readers!

There's more, though, to say about Fry Bread.

A few weeks ago, I gave a talk at the Santa Fe Indian Center, in Santa Fe, NM. I talked about the names of nations but I also talked about the range of hair color and skin tone in the book. See?

After the lecture, a family approached me to say how deeply moved they are by seeing a child with lighter skin and hair. Fry Bread pushes back on the expectation that Native people look the same (black hair, dark skin, high cheekbones etc.). That expectation means that adults don't hesitate to tell a Native child like the girl holding the cat that they are "not really an Indian" (or some variant of that phrase). That's such a damaging statement! When you hear an adult say that to anybody--but especially a child--stop them.

The final pages of Fry Bread can help you interrupt that kind of harmful statement. There, Maillard wrote that:

Most people think Native Americans always have brown skin and black hair. But there is an enormous range of hair textures and skin colors. Just like the characters I this book, Native people may have blonde hair or black skin, tight cornrows or a loose braid. This wide variety of faces reflects a history of intermingling between tribes and also with people of European, African, and Asian descent.It is quite the challenge to impart substantive information in an engaging way, but Maillard and Martinez-Neal have done it, beautifully, in Fry Bread. I highly recommend it! Published by Roaring Book Press (Macmillan) in 2019, I hope you'll order several copies for your bookshelves, and to give to Native families, too.

Update: October 23, 2019

In a comment, I was asked if the book has information about the history of fry bread and its impact on health of Native people. It does--and that is yet another aspect of what makes this book stand out.

One double paged spread shows Native people in shadow. The woman on the cover is telling kids about the long walk. The text is:

Fry bread is history

The long walk, the stolen land

Strangers in our own world

With unknown food

We made new recipes

From what we had

In the Author's Note, Maillard provides teachers and parents and librarians who do not know this history, with information they can use to prepare to use the book with kids. It is an exquisite author's note! It spans eight pages that correspond with the illustrated pages that are the heart of Fry Bread. And--they're footnoted! I don't recall seeing footnotes in an Author's Note before.

Maillard writes that people think the Navajo (Diné) were the first to make fry bread. He talks about how, across the country, Native people and our ways are resilient and here, today, in spite of efforts to weaken and destroy our nations and communities.

He writes that there are some Natives who are pushing back on the making and eating of fry bread. He wrote:

For these critics, fry bread is an easy target for a much larger problem of being forced to deviate from a traditional Indigenous diet.The larger problem, he writes, is a reality many Native communities face. There are no fresh food markets nearby, fast food is more readily available, and access to health care (like markets) is difficult. We know that fast food is unhealthy when eaten every day. Maillard makes that point about fry bread, too. Eating it everyday will lead to health problems.

As noted above, the Author's Note is exquisite for the depth of information it provides. I quoted that one sentence, but will also note that the sentence has a footnote! It goes to Devon Mihesuah's article, "Indigenous Health Initiatives, Frybread, and the Marketing of Nontraditional 'Traditional' American Indian Foods." In his Author's Note, Maillard provides 15 footnotes! Like I said... exquisite. And--I think--groundbreaking.

Monday, October 21, 2019

A First Look at Roanhorse's RACE TO THE SUN

In July of 2019, I received an ARC (advanced reader copy) of Rebecca Roanhorse's Race to the Sun. I did a short twitter thread as I looked it over. Below is that thread, with some light editing to the original tweets, for clarity. I assume that Roanhorse and Riordan, too, read my thread and that edits to the ARC will be made before the final printing of Race to the Sun. The book is due out in 2020.

Indigenous peoples weren't "Original Americans."

They weren't "First Americans" either.

They were people of their own unique nations, all of which pre-date the United States.

How are readers going to know which parts are fantasy and which are not?

I am currently reading Race to the Sun, making notes as I do. So far, I've met the main character. She is a Diné girl named Nizhoni who can see monsters. Because of that power, the monster she sees in the opening chapters tells her that it has to kill her.

But, a small stuffed horned toad on her shelf speaks to her, telling her she has to slay that monster. To do that she has to go to the Glittering World where she will meet the Sun, who is also known as The Merciless One, and who will give her the tools she needs to kill that monster.

Clearly, Roanhorse is using Navajo stories to create the characters in Race to the Sun. As such, people in the Diné Writers Collective will see this as appropriation. Would the Diné Writers view these characters as caricatures?

When I finish reading and thinking about the book, I will be back with a link to the review.

****

I have an ARC of Roanhorse's RACE TO THE SUN.

I was wrong to recommend her TRAIL OF LIGHTNING. Details: Concerns about Roanhorse's TRAIL OF LIGHTNING.

I was wrong to recommend her TRAIL OF LIGHTNING. Details: Concerns about Roanhorse's TRAIL OF LIGHTNING.

RACE TO THE SUN is in Rick Riordan's "Rick Riordan Presents" series. His use of his fame to launch writers of color is terrific. I haven't read the other book in Riordan's series.

His intro for RACE TO THE SUN is titled "The Original American Gods." That's a problem, for sure. His problematic intro looks like this:

His intro for RACE TO THE SUN is titled "The Original American Gods." That's a problem, for sure. His problematic intro looks like this:

THE ORIGINAL AMERICAN GODSDo you see why that's not ok? "Original American" erases the fact that the Diné people pre-date America.

Changing Woman. Rock Crystal Boy. The Glittering World. The Hero Twins.

Indigenous peoples weren't "Original Americans."

They weren't "First Americans" either.

They were people of their own unique nations, all of which pre-date the United States.

Moving from Riordan's intro to the book itself, I am pretty sure the Diné Writers Collective would say no to it, immediately. In their Open Letter, they state that Roanhorse appropriated Diné culture when she wrote TRAIL OF LIGHTNING. But they are also concerned with the content. They write that

Roanhorse often mischaracterizes and misrepresents Diné spiritual beliefs.and,

Roanhorse turns deities into caricatures.

They reference others who have appropriated and misrepresented Diné beliefs, including Tony Hillerman, Oliver LaFarge, and Scott O'Dell.

And they write that

We are concerned that this book attempts to convert our true ancestral teachings into myth and legend.

Upthread, I linked to the Diné Writers Collective letter. I hope you go read the entire letter.

It is signed by Esther Belin, Sherwin Bitsui, Chee Brossy, Dr. Jennifer Denetdale, Tina Deschenie, Jacqueline Keeler, Dr. Lloyd Lee, Manny Loley, Jaclyn Roessel, Roanna Shebala, Jake Skeets, Dr. Laura Tohe, Luci Tapahonso, and Orlando White.

It is signed by Esther Belin, Sherwin Bitsui, Chee Brossy, Dr. Jennifer Denetdale, Tina Deschenie, Jacqueline Keeler, Dr. Lloyd Lee, Manny Loley, Jaclyn Roessel, Roanna Shebala, Jake Skeets, Dr. Laura Tohe, Luci Tapahonso, and Orlando White.

In her Author's Note for RACE TO THE SUN, Roanhorse writes

I am just a writer of fantasy, not a culture keeper or scholar. This book should not be taken for a cultural text.

That is an icky, not-my-fault disclaimer because it echoes what Whiteness says (by "Whiteness" I mean white writers who argue that what they do in fiction doesn't have to be accurate because everybody knows that fiction isn't real. That is a disingenuous defense, no matter who says it.)

In that note, she also thanks Riordan for allowing her to:

...share some of what I know of the beauty of the Navajo culture with Navajo readers and the rest of the world.That kind of clashes with what she said, earlier (about the book not being a cultural text). First she says not to read the book as a cultural text, but then she says she's glad to share what she knows about Navajo culture.

How are readers going to know which parts are fantasy and which are not?

****

But, a small stuffed horned toad on her shelf speaks to her, telling her she has to slay that monster. To do that she has to go to the Glittering World where she will meet the Sun, who is also known as The Merciless One, and who will give her the tools she needs to kill that monster.

Clearly, Roanhorse is using Navajo stories to create the characters in Race to the Sun. As such, people in the Diné Writers Collective will see this as appropriation. Would the Diné Writers view these characters as caricatures?

When I finish reading and thinking about the book, I will be back with a link to the review.

Labels:

Race to the Sun,

Rebecca Roanhorse

National Parks, in AN INDIGENOUS PEOPLES' HISTORY OF THE US, FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

In the last few months, I (Debbie) have received a few emails about the National Parks. I have replied by directing individuals to An Indigenous Peoples' History of the United States, for Young People.

When Jean and I adapted Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's book into one that teachers could more readily use on their own or with students, we made choices on what to modify, keep, leave out, or expand.

Knowing that some families visit National Parks, we decided to expand a bit on that topic.

In Chapter 9, "The Persistence of Sovereignty," we wrote about the Yellowstone Park Act in a segment we titled "Pushing Back Against Legalized Land Theft." In that section we talk about several instances in which a tribal nation fought to have land taken from them to create a national park or forest, returned. One example is Blue Lake, taken from Taos Pueblo when President Roosevelt created Carson National Forest in 1906. For decades, they fought to have it returned.

As you can see from the screen cap of my Kindle copy of that page, we also have a "Did You Know" textbox about a legal term: reserved rights. That was deliberate on our part because we knew there was a case before the Supreme Court, about whether or not Clayvin Herrera, a member of the Crow Nation, had rights to hunt in the Bighorn National Forest.

When teachers introduce information about the National Park system, we hope our adaptation will help them provide students with a more critical look at how those lands came to be "national" parks.

And we hope they'll draw connections from history to the present day. They can do that, for example, by studying and talking about Clayvin B. Herrera v. State of Wyoming. It cited the reserved rights doctrine. The court, by the way, ruled in favor of Herrera.

When Jean and I adapted Roxanne Dunbar-Ortiz's book into one that teachers could more readily use on their own or with students, we made choices on what to modify, keep, leave out, or expand.

Knowing that some families visit National Parks, we decided to expand a bit on that topic.

In Chapter 9, "The Persistence of Sovereignty," we wrote about the Yellowstone Park Act in a segment we titled "Pushing Back Against Legalized Land Theft." In that section we talk about several instances in which a tribal nation fought to have land taken from them to create a national park or forest, returned. One example is Blue Lake, taken from Taos Pueblo when President Roosevelt created Carson National Forest in 1906. For decades, they fought to have it returned.

As you can see from the screen cap of my Kindle copy of that page, we also have a "Did You Know" textbox about a legal term: reserved rights. That was deliberate on our part because we knew there was a case before the Supreme Court, about whether or not Clayvin Herrera, a member of the Crow Nation, had rights to hunt in the Bighorn National Forest.

When teachers introduce information about the National Park system, we hope our adaptation will help them provide students with a more critical look at how those lands came to be "national" parks.

And we hope they'll draw connections from history to the present day. They can do that, for example, by studying and talking about Clayvin B. Herrera v. State of Wyoming. It cited the reserved rights doctrine. The court, by the way, ruled in favor of Herrera.

Tuesday, October 08, 2019

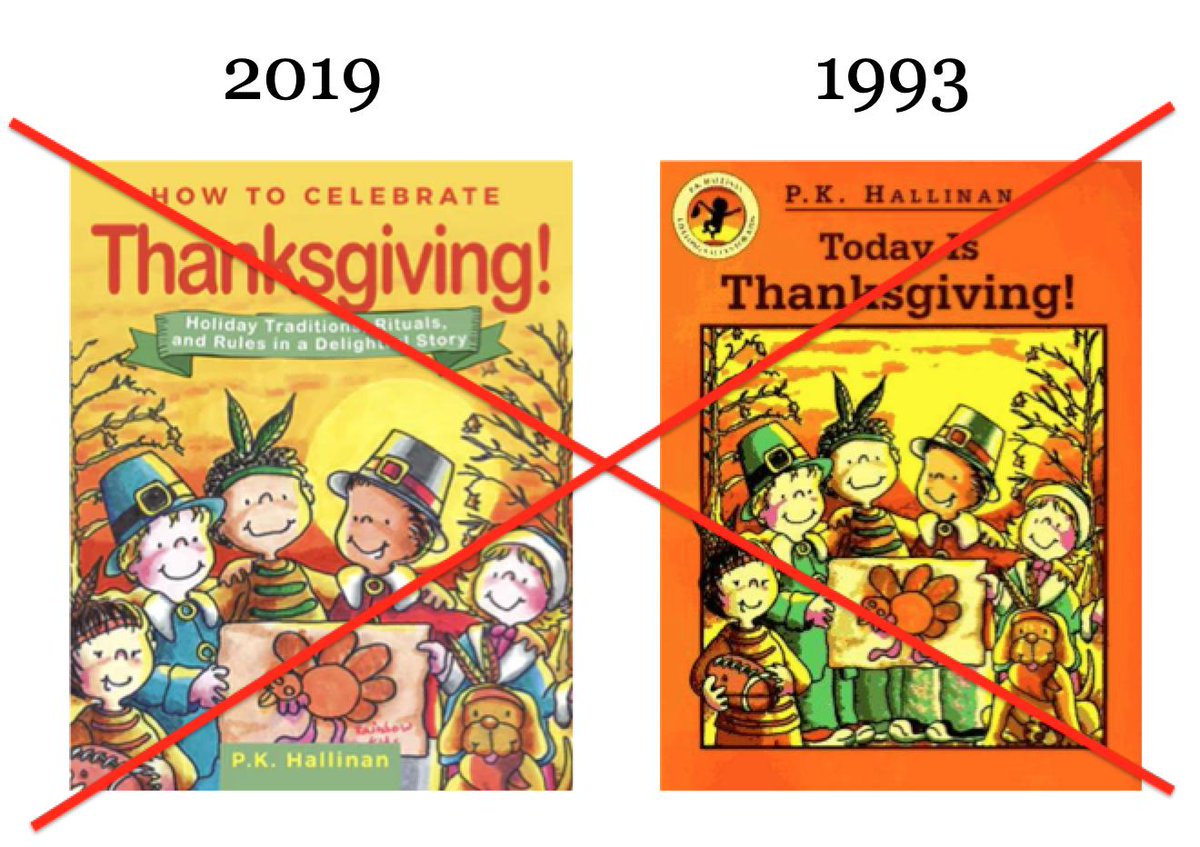

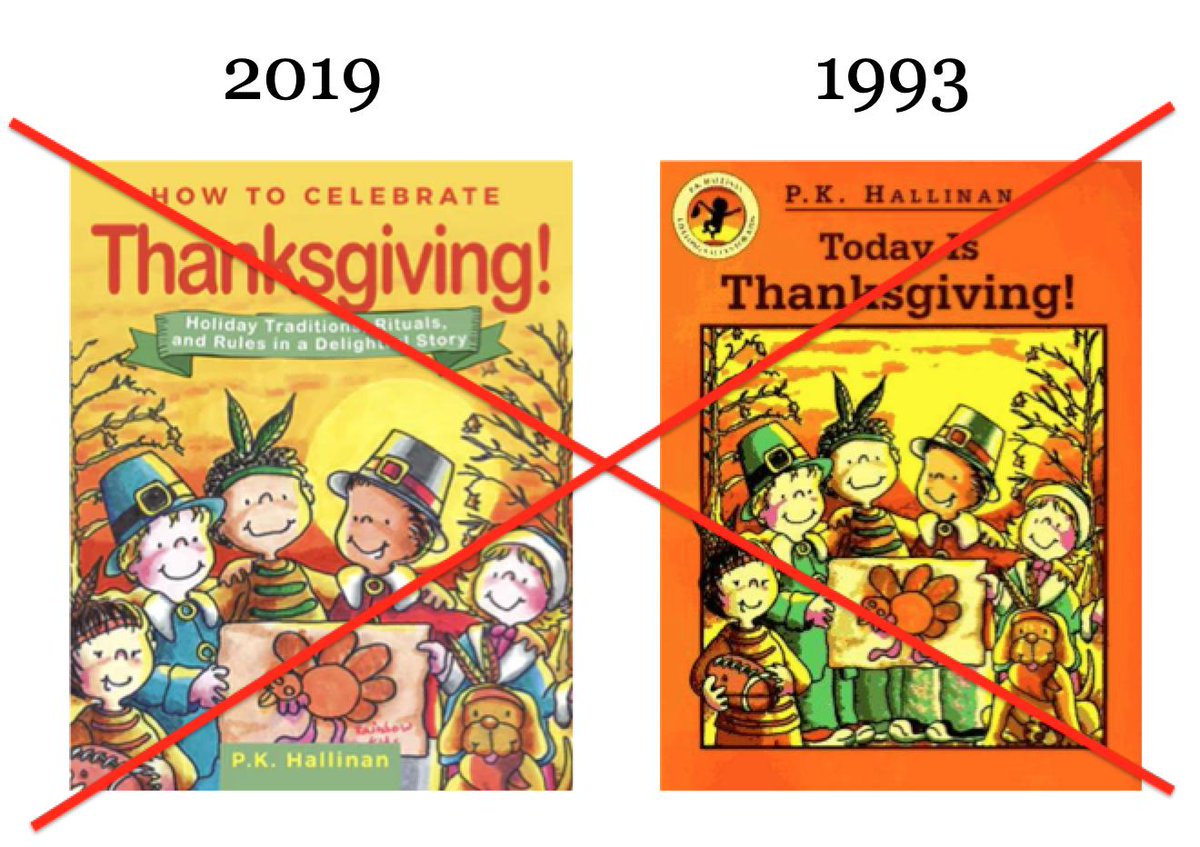

Not Recommended: HOW TO CELEBRATE THANKSGIVING! by P. K. Hallinan

Back in August of 2019, Elisa Gall tweeted the cover of How to Celebrate Thanksgiving: Holiday Traditions, Rituals, and Rules in a Delightful Story by P.K. Hallinan. It is due out on November 5 from Sky Pony publishing.

A conversation about the book also took place on Facebook, where someone noted that the book was first published in 1992 as Today Is Thanksgiving. I looked around and sure enough... the covers are the same. New title, but the same illustration:

The 1993 edition is available at the Internet Archive. I'll paste some images below. If you have the 2019 edition, do you see these images inside? The subtitle for the 2019 edition is "Holiday Traditions, Rituals, and Rules" and its "How To Celebrate" suggests it is a how-to book. The description of the new one sounds exactly like what I see in the old edition:

The story opens on Thanksgiving day with two children thinking about Pilgrims and Indians. Though I am careful to say that Native people can have fair hair and skin, I am pretty sure that these two kids are White.

Downstairs, their parents are cooking. The two children are shown going downstairs "descending on old Plymouth Rock." One has a comb tucked inside a headband. You can see it better when he sits down at the table to help his parents make pie:

Then, they go watch TV. That kid is still wearing the comb:

When the parade is over, the two kids get dressed and go outside to play football with their friends. The comb is gone. But, look closely at the eyes of the child in the red sweater. Dr. Sarah Park Dahlen has done presentations on the way that the eyes of Asian children are drawn in children's books. At her site, she's got the Ten Quick Ways to Analyze Children's Books for Racism and Sexism guide published years ago by the Council on Interracial Books for Children. Item #1 names slant-eyed "Oriental" as a stereotype.

Is that child shown that way in the 2019 edition?

The rest of the book is about the kids playing football and then going back inside to greet cousins. Then, they eat and play games that evening. The final page is reflections on the day.

The questions are for the editor and publisher. If the 2019 edition is identical to the 1993 edition, why is it being republished, as is, without any revisions to its anti-Native and racist Asian illustrations and ideology?

A conversation about the book also took place on Facebook, where someone noted that the book was first published in 1992 as Today Is Thanksgiving. I looked around and sure enough... the covers are the same. New title, but the same illustration:

The 1993 edition is available at the Internet Archive. I'll paste some images below. If you have the 2019 edition, do you see these images inside? The subtitle for the 2019 edition is "Holiday Traditions, Rituals, and Rules" and its "How To Celebrate" suggests it is a how-to book. The description of the new one sounds exactly like what I see in the old edition:

Parents and children alike will delight in this cheery book about Thanksgiving Day. From baking an apple pie to playing football on a crisp autumn morning to gathering around the table with friends and family, this adorable picture book depicts some of America’s most treasured family traditions.

The lively rhyming text and bright illustrations will not only delight and entertain your kids, but will also instruct. Hallinan gently encourages children to help with the preparation of the holiday meal, to spend time with family, and also to be grateful for the many blessings that they have been given.

The story opens on Thanksgiving day with two children thinking about Pilgrims and Indians. Though I am careful to say that Native people can have fair hair and skin, I am pretty sure that these two kids are White.

Downstairs, their parents are cooking. The two children are shown going downstairs "descending on old Plymouth Rock." One has a comb tucked inside a headband. You can see it better when he sits down at the table to help his parents make pie:

Then, they go watch TV. That kid is still wearing the comb:

When the parade is over, the two kids get dressed and go outside to play football with their friends. The comb is gone. But, look closely at the eyes of the child in the red sweater. Dr. Sarah Park Dahlen has done presentations on the way that the eyes of Asian children are drawn in children's books. At her site, she's got the Ten Quick Ways to Analyze Children's Books for Racism and Sexism guide published years ago by the Council on Interracial Books for Children. Item #1 names slant-eyed "Oriental" as a stereotype.

Is that child shown that way in the 2019 edition?

The rest of the book is about the kids playing football and then going back inside to greet cousins. Then, they eat and play games that evening. The final page is reflections on the day.

The questions are for the editor and publisher. If the 2019 edition is identical to the 1993 edition, why is it being republished, as is, without any revisions to its anti-Native and racist Asian illustrations and ideology?

Tuesday, October 01, 2019

Recommended: THE CASE OF WINDY LAKE

I've really enjoyed Marcie R. Rendon's first two Cash Blackbear mysteries. Marcie (White Earth Anishinabe) writes them for adults, but older teens will also find them engaging. I recommend them. They aren't the focus of this post; just wanted to mention Murder on the Red River and Girl Gone Missing before moving on to the actual topic.

Michael Hutchinson is a citizen of the Misipawistik Cree Nation, and his The Case of Windy Lake (Second Story Press, 2019) is the first installment in the Mighty Muskrats Mystery series.

Hutchinson's Mighty Muskrats are four cousins--Atim, Chickadee, Otter, and Sam-- who live on the Windy Lake First Nation (pretty sure this is a fictional location) in what's currently called Canada. These tweens are smart, curious, and resourceful. They operate out of an incapacitated school bus on the outskirts of their reservation community.

It's tempting to do a chapter-by-chapter look at what makes this book so appealing -- but with mysteries, that can mean spoilers. So I'll just sum up.

The first case the Muskrats take on is the disappearance of an archaeologist who was working for a mining company in the area. There's a subplot involving a beloved older cousin who actively opposes the mining company's actions that she knows will endanger the community's water supply. A lot of Indigenous communities have dealt with well-educated fools coming in to study them, and lots of Native kids have relatives who are involved in Indigenous environmental rights (and they may be activists themselves). The book's main antagonist is a white mine manager; when he talks to the kids and their family members we see the same entitled hostility and disrespect Indigenous people encounter in real life today when they stand against exploitation and destruction of their resources.

The kids use the internet as well as knowledge of their community and their natural surroundings to solve the mystery, and they don't get in the way of law enforcement (their uncle) or need to be rescued. There's a nice all-for-one-and-one-for-all feeling about their relationships. For example, when they're about to go get information from someone in a restaurant, Atim says he's hungry. Chickadee asks, "Do we have any money?" and Otter pulls some from his pocket. They count it ... triumph! They can split an order of fries and a pop, and that's fine with everyone.

Details add to the sense of place, as in Hutchinson's description of that restaurant:

Anyone looking in this book for a dysfunctional fictional rez community will have to look elsewhere. The people of Windy Lake have their troubles, but ties within families and between neighbors are solid and caring. And the resolution of the mystery is ... affirming, and that's all I'll say about it. You'll just have to read it to find out more. Then we can wait together for the next Mighty Muskrats book.

EDITED 10/3/19 with good news from two commenters. Val (10/2/19) notes that you can read the first chapter of The Case of Windy Lake on the Second Story Press Web site! And Cheriee Weichel reports that the sequel, titled The Case of the Missing Auntie, will be available in March 2020.

Edited 10/18/19 to add a link to CBC coverage of The Mighty Muskrats!

--Jean Mendoza

Michael Hutchinson is a citizen of the Misipawistik Cree Nation, and his The Case of Windy Lake (Second Story Press, 2019) is the first installment in the Mighty Muskrats Mystery series.

Hutchinson's Mighty Muskrats are four cousins--Atim, Chickadee, Otter, and Sam-- who live on the Windy Lake First Nation (pretty sure this is a fictional location) in what's currently called Canada. These tweens are smart, curious, and resourceful. They operate out of an incapacitated school bus on the outskirts of their reservation community.

It's tempting to do a chapter-by-chapter look at what makes this book so appealing -- but with mysteries, that can mean spoilers. So I'll just sum up.

The first case the Muskrats take on is the disappearance of an archaeologist who was working for a mining company in the area. There's a subplot involving a beloved older cousin who actively opposes the mining company's actions that she knows will endanger the community's water supply. A lot of Indigenous communities have dealt with well-educated fools coming in to study them, and lots of Native kids have relatives who are involved in Indigenous environmental rights (and they may be activists themselves). The book's main antagonist is a white mine manager; when he talks to the kids and their family members we see the same entitled hostility and disrespect Indigenous people encounter in real life today when they stand against exploitation and destruction of their resources.

The kids use the internet as well as knowledge of their community and their natural surroundings to solve the mystery, and they don't get in the way of law enforcement (their uncle) or need to be rescued. There's a nice all-for-one-and-one-for-all feeling about their relationships. For example, when they're about to go get information from someone in a restaurant, Atim says he's hungry. Chickadee asks, "Do we have any money?" and Otter pulls some from his pocket. They count it ... triumph! They can split an order of fries and a pop, and that's fine with everyone.

Details add to the sense of place, as in Hutchinson's description of that restaurant:

The jukebox was playing "Love Hurts" by Nazareth. Scarred and scuffed blue-and-once-white tiles covered the floor. Sun streamed in from windows that overlooked the gas pumps, the parking lot, and the trucks buzzing north up the highway.... Half the restaurant was occupied by First Nations people hunkered over cups of coffee. A few tables held non-local miners and highway travelers. Laughter was coming from most tables and jokes were being shared between a few. The quiet tables held smiling Elders.The author's ability to show the reader a scene or a relationship is likely one reason The Case of Windy Lake won the Second Story Press Indigenous Writing Award.

Anyone looking in this book for a dysfunctional fictional rez community will have to look elsewhere. The people of Windy Lake have their troubles, but ties within families and between neighbors are solid and caring. And the resolution of the mystery is ... affirming, and that's all I'll say about it. You'll just have to read it to find out more. Then we can wait together for the next Mighty Muskrats book.

EDITED 10/3/19 with good news from two commenters. Val (10/2/19) notes that you can read the first chapter of The Case of Windy Lake on the Second Story Press Web site! And Cheriee Weichel reports that the sequel, titled The Case of the Missing Auntie, will be available in March 2020.

Edited 10/18/19 to add a link to CBC coverage of The Mighty Muskrats!

--Jean Mendoza

Sunday, September 29, 2019

Not Recommended: AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED

I often do a Twitter review of a book -- which means I write and send tweets as I read the book. I did that yesterday as I made my way through And Still the Turtle Watched.

I try to compile those twitter threads here, on AICL. I usually do some light editing to make them flow a bit better than they did on Twitter. Beneath the image of the book cover and the "Not Recommended" rating, you'll find my Twitter review. It is rough--unfolding as I went. I hope it makes sense! If not, let me know.

****

This morning, I was asked about AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED. Do I recommend it? (No.)

Written by Sheila MacGill-Callahan and illustrated by Barry Moser, it came out in 1996 from Puffin Books.

I found it on an episode of Reading Rainbow. So... twitter review! There's several videos of that episode on Youtube. I don't know if RR is ok with that. As the episode opens, I see this thread is also going to critique how RR produced the segment.

It opens with Levar in a forest. The music is flute, some bells, drums... (me: sigh)

Written by Sheila MacGill-Callahan and illustrated by Barry Moser, it came out in 1996 from Puffin Books.

I found it on an episode of Reading Rainbow. So... twitter review! There's several videos of that episode on Youtube. I don't know if RR is ok with that. As the episode opens, I see this thread is also going to critique how RR produced the segment.

It opens with Levar in a forest. The music is flute, some bells, drums... (me: sigh)

Levar says that hundreds of years ago, Indians "lived here" in a forest in western America. I hope this entire segment doesn't stay in that past tense.

Levar says white men came to their lands and took it and its riches. The forest and its creatures watched. The book in the segment (AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED) is about one of those creatures.

[Me, groaning as I continue to watch the video]... More drum and flute and then someone starts to read the book in a deep kind of fake Indian voice... [sigh] It is Michael Ansara, an actor who played a lot of "Indians" on TV and in movies. [I'm sighing but trying not to laugh, too.]

Reading Rainbow is back, isn't it? Are they on twitter???

[Goes to look....] Yeah, they are.

@readingrainbow -- please don't do this sort of thing again.

[Goes to look....] Yeah, they are.

@readingrainbow -- please don't do this sort of thing again.

Ok, so Michael Ansara starts reading the story.

"Long ago when the eagles still built their nests along the river" (I guess they weren't doing that in 1996), an old man and his grandson stood beside a large rock. [I guess I could be glad it says "old man" and not "a shaman."

"Long ago when the eagles still built their nests along the river" (I guess they weren't doing that in 1996), an old man and his grandson stood beside a large rock. [I guess I could be glad it says "old man" and not "a shaman."

Old man says he's gonna carve that rock into turtle, who will be the eyes of Manitou. He will watch the Delaware [but... shouldn't he watch those white fellas?] and be their voice to Manitou. He tells the boy that he'll bring his children (and they'll bring their children) to that turtle. Old man got to work, making the turtle. "And then, the turtle watched" the seasons change from one to another. But he was happiest in summer when the children came, and then their children's children, and then their children's children. But as time wore on, fewer children came to greet the turtle. He wonders if he "watched badly. Does Manitou no longer hear me?"

Pausing the vid to say that the author is taking some huge liberties in writing all of this. Is it supposed to be a "myth" or a "legend"? Looked it up on WorldCat. Not seeing anything that says "Indians of North America" but there's no doubting that people think this is a Native story. With that turtle and spear on the cover, you know that's what they were going for:

Several libraries near me have it on the shelf... does it still circulate? Is it getting used in storytimes.... in your library? Or school?

Dictionaries tell me that "manitou" is a spirit or force. The author says the people in her story are Delaware. She's creating words for what she thinks is a Delaware spirit or force. She was born in the UK. Guessing she was White (she is deceased).

Back to the vid. "... one day, strangers came. They did not greet the turtle." The stranger shown is a farmer and horse. "They did not speak to Manitou." They chopped down trees; turtle watched and "does not understand." More strangers came. Now there's a city.

He watches the water turn brown; at night lights glowed "near the ground" and he can't see the stars in the sky. He gets sad. "Why watch?" he says. "My children have not come for many moons."

Then one day some boys come to the rock. They're in black leather jackets. They point at him. He gets happy. He thinks they're children who have come to see him. "Thank you, Manitou" he says. Then he heard a sound. He feels cool wetness on his eyes. He can't see anymore.

The sound is a can of spray paint.

"He cannot watch for Manitou!"

The sound is a can of spray paint.

"He cannot watch for Manitou!"

His heart cracks. Days, months, years pass. Nobody watches for Manitou.

You're supposed to feel sad. It is a sad story but it is SAPPY WHITE MAN INDIAN stuff.

Where, I wonder, did that old man's children go? They've just disappeared.

Where, I wonder, did that old man's children go? They've just disappeared.

That hokey Hollywood drum beat is in the background during these sad bits. Then, a man comes! He knows the Delaware "once summered here." He's got a shovel. He hopes to find something "they left behind."

Sigh. Past tense verbs

Sigh. Past tense verbs

He looked all day and found nothing. He was tired. Then he saw the rock! Covered with graffiti. The turtle didn't know the man was there. That paint had blinded his eyes. He felt the man's hand on his shell.

The man came back with workmen. They put the rock on a truck, unloaded it somewhere else. He feels them working on him. His eyes start to clear and he can hear again. He's not outdoors anymore. He's inside at a botanical garden where children come to see him. And they will bring their children and their children's children. And he "will speak of them, to Manitou."

Some of you know I caution you for making judgments on a child's identity based on what they look like. I hold to that--but in this case, I am confident in saying that the author didn't mean for us to think the kids on the last page are Native. For her, Native people are extinct.

NOW: if you're a teacher who might, in fact, have Delaware children in your class, how do you think THEY feel abt this story?

The story is over, and we're back with Levar who tells us that the Delaware people in the story chose turtle to watch because they think he is wise. He goes on to talk about other animals and "legends."

The episode shifts to a segment about eagles and people who study them. At the end, Levar is back in that forest breathing the fresh air. The RR shows ended with book recommendations. This one includes A RIVER RAN WILD (I don't rec that one either). The next recommendation is THIRTEEN MOONS ON TURTLES BACK by Bruchac. I'll have to look for that one. Update on Oct 3 2023: I no longer recommend Bruchac's work. For details, see Is Joseph Bruchac truly Abenaki?

Circling back to why I started this thread: I do not recommend AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED. It looks like a Native story, but is it, really? Or is it something the white (British) writer made up?

What happened to the Delaware people in the story? They just disappear.

But they didn't. You know that, right?

Readers are supposed to feel bad for the turtle being abandoned by the Delawares and then abused by those boys who graffitied him, but then we're supposed to feel good that a white guy rescues the turtle and puts it in a garden. But if there really was a turtle like that, I think that the Delaware people might want it left alone--not hauled off to a botanical garden. I know--ppl think "garden" and think that's fine but truly, taking Native items is a no-no. Don't do it!

A lot of writers use Native themes in stories about care of the environment. Those stories, however (and there are several) show Native people as gone. They fuel a factual error about our existence. We're still here. (And it grates to say "we're still here.")

Back with more to say about AND STILL THE TURTLE WATCHED. I found another video of it online. Seems that the Reading Rainbow version leaves out some of what I'm seeing in this second video.

The Reading Rainbow version doesn't include the last page, which tells readers that the turtle is in the Watson building at the New York Botanical Garden. I looked around a bit and found an article in the New York Times, dated March 25, 1988 about a box turtle petroglyph.

From the article I learned that the New York Botanical garden is huge: 250 acres. There, somewhere, a turtle petroglyph was found in 1987 by Edward J. Lenik, an archeologist from the NYC Landmarks Preservation Commission. An amateur archeologist had found it ten years before.

It was etched into a boulder. That's it on the left (below), as shown on the Botanical Garden website. On the right is the three-dimensional carving shown in And Still the Turtle Watched.

The NYT article says the boulder it was on had been vandalized. When they found it in 1988 they took it inside to protect it. The article suggests it was made by Delaware Indians 400-1000 years ago but also notes it could be a forger's work.

The petroglyph is small: 3 3/4 inches long by 2 1/2 inches wide. The article says they talked to someone at the American Indian Community House in NYC but it doesn't say what (if anything) they said about it.

If the botanical folks think it is Delaware, they could get in touch with the Delaware people.

All that aside, I still circle back to the idea that a non-Native woman turned that petroglyph into what looks like/sounds like a Native story.

All that aside, I still circle back to the idea that a non-Native woman turned that petroglyph into what looks like/sounds like a Native story.

I wonder if the Delaware people use that word (manitou) in their stories?

Wednesday, September 25, 2019

Recommended: INDIAN NO MORE by Charlene Willing McManis with Traci Sorell

Indian No More by Charlene Willing McManis with Traci Sorell, cover art by Marlena Myles, is due out in September of 2019 from Tu Books. Written with middle-grade readers in mind, I highly recommend it for them, but for teens and adults, too.

When I started grad school in the 1990s, I remember reading that children's books can fill the huge gaps in what textbooks offer.

I doubt, for example, that there's a single textbook out there that teaches kids about the termination programs of the 1950s.

Indeed, most non-Native people reading this review of Indian No More probably don't know what the termination program was!

Those who do know what I'm talking about likely didn't learn it in school. They learned about it because their family--like Charlene Willing McManus's--was caught in a government program that determined they were no longer Native.

Here's the book description for Indian No More:

When I started grad school in the 1990s, I remember reading that children's books can fill the huge gaps in what textbooks offer.

I doubt, for example, that there's a single textbook out there that teaches kids about the termination programs of the 1950s.

Indeed, most non-Native people reading this review of Indian No More probably don't know what the termination program was!

Those who do know what I'm talking about likely didn't learn it in school. They learned about it because their family--like Charlene Willing McManus's--was caught in a government program that determined they were no longer Native.

****

Here's the book description for Indian No More:

Regina Petit's family has always been Umpqua, and living on the Grand Ronde reservation is all ten-year-old Regina has ever known. Her biggest worry is that Sasquatch may actually exist out in the forest. But when the federal government signs a bill into law that says Regina's tribe no longer exists, Regina becomes "Indian no more" overnight--even though she was given a number by the Bureau of Indian Affairs that counted her as Indian, even though she lives with her tribe and practices tribal customs, and even though her ancestors were Indian for countless generations.