In my experience, a lot of people don't remember or realize that classic, award-winning, or popular books have Native content in them that is biased, stereotypical, or just flat out incorrect. I and others have written about several of those books. That writing is here on AICL but in research and professional articles and book chapters, too.

This post is a list of links to some of that writing. If you're a teacher or professor interested in using a children's or young adult book to teach critical literacy, these will work well for that sort of analysis.

Arrow to the Sun

Caddie Woodlawn

The Girl Who Loved Wild Horses

Island of the Blue Dolphins

Little House on the Prairie

Sign of the Beaver

Touching Spirit Bear

What we need are books by Native writers! Check out AICL's Best Books lists.

- Home

- About AICL

- Contact

- Search

- Best Books

- Native Nonfiction

- Historical Fiction

- Subscribe

- "Not Recommended" books

- Who links to AICL?

- Are we "people of color"?

- Beta Readers

- Timeline: Foul Among the Good

- Photo Gallery: Native Writers & Illustrators

- Problematic Phrases

- Mexican American Studies

- Lecture/Workshop Fees

- Revised and Withdrawn

- Books that Reference Racist Classics

- The Red X on Book Covers

- Tips for Teachers: Developing Instructional Materi...

- Native? Or, not? A Resource List

- Resources: Boarding and Residential Schools

- Milestones: Indigenous Peoples in Children's Literature

- Banning of Native Voices/Books

Showing posts sorted by date for query arrow to the sun. Sort by relevance Show all posts

Showing posts sorted by date for query arrow to the sun. Sort by relevance Show all posts

Tuesday, October 23, 2018

Tuesday, January 31, 2017

Can Kiera Drake's THE CONTINENT be revised?

Editors note, 2/19/18: See my review of the revised book.

Kiera Drake's The Continent was slated for release in January of 2017 from Harlequin Teen.

Questions from readers, however, prompted Harlequin Teen to postpone it. They didn't say they were canceling it. Just postponing it, which means they are trying to... fix it.

Can Drake revise The Continent so that it will, eventually, be released?

My answer: no.

I have an arc (advanced reader copy). I hope my review of that ARC is useful to the author, her editor, her publisher, and anyone else who is writing, editing, reviewing, or otherwise working with a book that depicts Native people.

Let's start with the synopsis:

Note: For each chapter below, summary is in plain text; my comments are in italics.

Chapter One

Chapter one opens with Vaela Sun's 16th birthday party in an ornate place in the Spire (a hundred million other people live there, too). Vaela has received three gifts from her parents. One is a ruby pendant on a gold chain that brings out the gold color of her hair. The second one is an elegantly framed map of the Continent that she drew based on her studies (she's a cartographer). The third gift is an official certificate of travel to the Continent. Trips to the Continent are very rare. There are only ten tours in a year, and only six guests on each tour.

My comments: Clearly, these are the most affluent people in this place called "the Spire." The name of the place embodies privilege. These two families are at the very top of that privilege.

Vaela and her parents dine with the Shaw's, who are highly placed in the Spire and used their influence to make the trip possible. At dinner, Vaela's father (Mr. Sun) and Mr. Shaw have this exchange (p. 15):

These wealthy white people, speaking of the Topi/Hopi as they do, is revolting. Native people, for these wealthy white people, are entertainment. When she wrote this book, did the author imagine that Native teens might read it?

Vaela's mom (Mrs. Sun) was hoping they wouldn't see any bloodshed, but Aaden Shaw asks if there's any other reason to go to the Continent. Though there are spectacular landscapes, he says (p. 15),

Mr. Sun and Mr. Shaw talk about how, from the safety of the heli-plane, they can observe war. Mr. Shaw says (p. 16):

Chapter Two

The Shaws and the Suns board the plane. Mrs. Shaw is surprised with the small windows. Aaden tells her (p. 25):

The plane takes off. Later, looking out a window, Aaden sees four natives. Mrs. Shaw is thrilled and asks if they're Aven'ei or Topi (p. 31):

Chapter Three

Everyone is unsettled by what they saw. Vaela tells her dad she's fine. She thinks (p. 34):

My comments: Aaden's remarks about war and violence as part of the human condition... what to make of that?

Chapter Four

The plan is an airplane tour of the Continent. The steward of Ivanel is their tour guide, pointing out geography, where the fights are taking place, and that of the land masses of their planet, the Continent is the least populated. Its population is in decline due to warfare. They fly over an Aven'ei town, and then (p. 47):

Pueblo Bonito is in Chaco Canyon. It is one of many sites like that, in the Southwest. For a long time, the National Park Service called them homes of the Anasazi--who had disappeared--but today, that error is gone. These are all now regarded as homes of Ancestral Puebloans. Vaela, and perhaps Kiera Drake, look upon them and thinks of ants. Insects. Need I say how offensive that is?

The plane gets low enough for Vaela to see the villagers, who are "singularly dark of hair, with beautiful bronzed skin" (p. 47).

My comments: That's one of the (many) passages that needed some work. The Topi village is in the icy, frozen north. How, I wonder, can she see the skin color? Later we're going to read about their clothing for this climate.

Aaden is drawn to the buildings, exclaiming (p. 47):

My comments: Though the amount of space Drake gives to the scene is just over a page in length, her description makes it loom large. It feels gratuitous, too. Intended, I think, for us to remember how brutal war is--but especially how brutal the Topi are.

Chapter Five

Back at Ivanel, Vaela grasps the violence in a way she had not, before. She understands the difference between spectacle and death. Rather than go up in the plane again, Vaela and Aaden will go on a walking tour, led by the steward. His name is Mr. Cloud. He is a Westerner and has "beautiful dark skin" and "blue eyes so pale they are nearly white" (p. 55). Aaden and Vaela talk about the battle. Recalling history she says (p. 59):

He also tells her that when the Continent was discovered 270 years ago, the Four Nations made a treaty amongst themselves that prohibited them from giving weapons to anyone on the Continent. There was trade, however, for a while. The East got lumber from the Aven'ei, and gave the Aven'ei agricultural wealth (crops and cattle). Vaela wonders why the Aven'ei didn't join the Four Nations. Aaden tells her that part of the treaty said that, in order to join, they would have to stop being a warring country. If they did that, the Topi would massacre them.

My comment: In each passage about the Topi and the Aven'ei, we see more and more that of the two, it is the Topi who are most primitive.

Chapter Six

The next day, the group gets on the plane again for another tour. Something goes wrong. Vaela's dad puts her in a safety pod. The plane crashes.

Chapter Seven

The pod lands in snow. After the third day, Vaela sets off, hoping to get to Avanel. At the end of the chapter, she's exhausted. Sitting against a tree, she hears what she thinks is the rescue plane.

Chapter Eight

Vaela gets up and runs towards the sound, then to a field. At the far end, she sees "a Topi warrior" bent over in the snow, a hatchet and dead squirrels beside him. He doesn't see her, so she decides to run into the field and wave at the plane. She does, but another Topi does see her. He's got red and yellow paint on his face and a quiver of arrows on his back. "The warrior's expression" is one of curiosity, not fierce. He calls to the other one. She runs, an arrow whizzes past her. She falls. He catches her, ties her hands together, rolls her over onto her back and looks into her face. His breath reeks of fish and decay as he speaks to her. The other warrior joins them. One jabs an arrow into her thigh. He hits her and she passes out.

My comments: Drake's use of "warrior" when she could have said "man" adds to the overall depiction of the Topi as warlike. That first guy? He was hunting. We don't know about the second one. But having his breath smell of decay... Drake is slowly but surely making the Topi out to be less than human.

Chapter Nine

Vaela comes to. She's on the ground on her back. The first Topi warrior she saw is with her. He grins at her; she notes his teeth, "blackened by whatever root he is chewing" (p. 88). He gives her some meat and berries. The other one returns later. Using a knife he draws a map in the dirt. She shows him where the Spire is.

Evening comes and the two men drink, "becoming increasingly boisterous" (p. 91). The first one finally passes out. The second one, however, yanks her to her feet and pulls her to him. There's a sticky white substance at the corners of his mouth. He buries his face in her hair and then starts kissing her her face and neck. She knows his intentions are "lustful." Suddenly, he falls away, a knife embedded in his neck. Another man, clad head to toe, in black. In the firelight she sees his "high cheekbones, dark almond-shaped eyes that slope gently upward at the corners, full lips" (p. 94). He speaks to her, in English.

My comments: Ah... the Drunken Indian stereotype. This drunk Topi, however, goes further. He's going to rape this blond haired white woman. This is SUCH A TROPE. Some stores have rows of romance novels with a white woman on the cover, in the arms of an Indian man. She might be struggling; she might not be. He is usually depicted as handsome.

Drake's menacing Native man is more like what we see in children's books. Like... this page in The Matchlock Gun:

Or in this scene from the television production of Little House on the Prairie (the part where they approach Ma is at the 1:45 mark, and again, at the 2:30 mark):

Here's a screen cap from the 2:10 mark:

Chapter Ten

Hearing English spoken to her is a healing ointment on her heart. He asks where she is from. She tells him she's from the Spire (p. 96):

My comments: Another trope! In children's books about European arrival on what came to be known as the American continent, Native people are shown as being in awe of Europeans.

A small point, but annoying nonetheless: As Aaden noted in chapter five, the Aven'ei adopted English. I suppose Drake wrote that into the story so that Vaela and Noro could easily communicate, but some of the logic of words/concepts he knows (and doesn't know) feels inconsistent to me. He doesn't know the word heli-plane but does know menagerie (and later, "propriety" but doesn't know "technology").

Last point: Damsel's in distress, saved by a man, are annoying. Also annoying are female characters who run, trip, and are caught by bad guys. That happened in chapter five when Vaela was running away from the Topi man.

The next day, Noro thinks he should tend to Vaela's wounded thigh, but she's uneasy with having him touch her or see her bare leg. She relents, he cleans and bandages the wound, and she tells him this is the second time he's saved her. They set off.

That evening, Noro asks if other people in the Spire look like Vaela, with her "golden hair" and "eyes like the leaves of an evergreen" (p. 105). She tells him that the people in the West are dark-skinned with pale blue eyes, those in the North have pale skin and white hair, those in the South are olive-skinned with dark hair, and those in the East (where she is from) are often pale, with blue or green eyes.

My comments: Another trope! Time and again in children's books, writers depict Native people as in awe of blonde--or sometimes red--hair.

Chapter Eleven

Vaela is getting sick. Towards the end of the chapter, Noro has to carry her for awhile. He wants to take her to a healer when they get to his village but she's afraid of what that healer will do (leeches are one possibility). She insists that Noro take her to the village leaders first. He agrees. They arrive at the village.

Chapter Twelve

As they walk through the village, Vaela is surprised and impressed at their rich culture. She meets Noro's ten-year-old brother, Keiji. In Noro's cottage, she notices a tapestry on the wall, and a carved bookcase full of books. She learns that Noro is one of the few assassins they have. They "eliminate Topi leaders." Without the assassins, "the Topi would have wiped us from the Continent long ago" (p. 125).

My comments: Earlier, I noted that the author (Kiera Drake) was, as the story unfolded, drawing a distinction between the Topi and the Aven'ei. The description of the tapestry and books add a lot. They are definitely not "uncivilized."

Vaela and Noro go to the meeting with the village leaders. They deny her request to be taken back to Ivanel because it is dangerous to try to be on the sea during this part of the year, and, because they're at war. Noro takes Vaela to Eno's (the healer) cottage.

Chapter Thirteen

Vaela spends several weeks under the care of Eno. Keiji visits but Noro does not.

Chapter Fourteen

When she's well, Keiji takes her to her own cottage. It is furnished much like Keiji and Noro's. Sofa, bookshelf, books. She looks around the main room, the kitchen, her bedroom, and a room with a bash basin and a chamber pot. Later she goes to visit Noro, who tells her the leaders want to see her again, to assign her a job. She tells Noro about "the Lonely Islands" (p. 148) of the Spire. Citizens who don't want to work are "invited" to relocate to that place. Some choose to go, others are sent.

Chapter Fifteen

Vaela begins work as a field hand, scooping and hauling cow manure. Noro gave her some money to use until she gets paid. She goes to the market, where an old woman remarks on her gold hair, with its "strings of sunshine." The woman offers Vaela three, then four, then five oka (coins) for it but Vaela says no. Vaela meets a young woman, Yuki Sanzo (they're going to become good friends).

My comments: the fascination/value again of blonde hair...

Yuki tells her the war is because of a debt, and that now, the Topi (p. 159):

My comments: This depiction of the Topi as hunter/gatherers who don't know how to farm is common, in fiction, nonfiction, and textbooks, too. It is an error, especially given that the Topi are based on the Hopi, who for thousands of years, cultivated corn in the southwest. Doing that required sophisticated irrigation systems. This is well-described in Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz's book (An Indigenous Peoples History of the U.S.) This widespread misrepresentation lays the groundwork for justifying occupation and colonization of Native lands.

Chapter Sixteen

Vaela does her work, and thinks about how she could make a map that the Aven'ei could use in their war against the Topi.

Chapter Seventeen

On a visit, Yuki realizes that Vaela doesn't know how to take care of herself or cook, either. She teaches her. Noro visits; Vaela tells him she wants to visit the council about improvements in the village. Specifically, she tells him about toilets and how they work. He's disgusted with the idea of having a privy inside the house.

Chapter Eighteen

Vaela tells Yuki the villagers give her odd looks. Yuki tells her they're just wary of her. Yuki tells her she needs to have a knife with her at all times because the Continent is not the Spire. Vaela thinks the Topi wouldn't come to the village. Yuki isn't sure of anything.

Chapter Nineteen

Keiji starts teaching Vaela how to fight; Noro calls Vaela "miyake" which means "my love."

Chapter Twenty

Noro reports that there are Topi nearby and asks Vaela to draw a map of where they are; they take the map to the leaders. Noro gives Vaela a set of throwing knives.

Chapter Twenty-One

When Noro is teaching Vaela how to use a knife to kill someone, quickly, and quietly. Vaela asks if that is the technique that Noro used on the Topi who found her after the crash. He nods; she says that the Topi was kind to her, that he gave her food. Noro gets angry that she grieves for the Topi, and tells her she cannot look upon them as men. They are the enemy. She tells him the Topi are people, too. Yuki is angry at her, too, telling her that the Topi might put her head on a pike. Vaela counters that the Aven'ei are brutal, too, and recounts the bodies they saw from the plane. Another person who is with them, Takashi, says that Vaela makes a valid point. Yuki and Takashi start arguing. Vaela tries to get them to stop, and Yuki tells her that she is, and will always be, an outsider.

My comments: in that passage and before, Vaela seems to be wanting to help. That, however, is another problem with how she is developed. She's a white character, entering a place of Native and People of Color, attempting to improve their lives--according to her standards. This a white savior.

Chapter Twenty-Two

The Topi come into the village. Noro goes out to fight, telling Vaela to stay in the bedroom with her knives. But later, she starts thinking she can at least kill one Topi (p. 216):

My comments: When I started this chapter-by-chapter read, I noted that a Native reader--and especially one who is Hopi--would have a different experience than, perhaps, most others who read these passages about killing. To make them as brutal as possible, this Topi is firing at a child (remember, Keiji is only ten years old).

Chapter Twenty-Three

They take Keiji to a healer. Noro arrives shortly. Vaela asks if he killed the Topi archer and replies "good" when he says he did. Noro tells her she would not have killed a Topi. Instead, she would have been killed, and if not that, she'd have been "captured, raped and beaten--kept to be used by any savage who wanted you" (p. 225).

My comments: On the heels of the Topi warrior who shot a child, Drake puts forth a scenario where a "savage" rapes, beats, and uses the blonde as he wishes.

Vaela tells Noro she wants to return to the Spire to get help. Noro tells her they already know what is happening, that they've known for over 200 years and not intervened. Vaela is sure she can persuade them. She promises she'll return (p. 229):

My comments: Again, Drake depicts her main character as a white savior.

Chapter Twenty-Four

The village leaders approve of Vaela's plan to return to the Spire. Noro will take her to Ivanel.

Chapter Twenty-Five

Vaela and Noro arrive on Ivanel. He's impressed with the building and the glass windows. She tells him it has other things, too, like an indoor swimming pool, racquet courts, cedar saunas, and toilets. Soon after that, they say their good-byes. Noro leaves Ivanel.

My comments: that scene strikes me as tone deaf and heartless. Didn't they just spend hours with Keiji, worried for his life? I guess out-of-sight, out-of-mind...

Chapter Twenty-Six

Valea plans for her return to the Spire where she will try to persuade the Heads of State to intervene.

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Vaela arrives at her home at the Spire.

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Vaela goes to the Chancellery for her meeting with the sweet-faced Mr. Lowe of the West who has dark skin and pale eyes, Mr. Wey of the East who is a scholarly man in spectacles, Mr. Chamberlain of the South, who is sickly looking, has a slender mustache, and watery eyes, and Mrs. Pendergrast of the North who looks like she spent her life sucking on sour candy. Vaela notices that Mr. Lowe and Mrs. Pendergrast avoid each other.

Mr. Lowe thinks the Aven'ei could be relocated to the Spire. Mrs. Pendergrast thinks they're uncivilized and should not be brought there. Vaela tells them the Aven'ei are not uncivilized, but that they wouldn't leave their homes. Mr. Lowe asks her what she wants, then, if not to help them relocate.

Vaela says she wants the Spire to build a wall between the Aven'ei and the Topi. Mr. Lowe thinks it a good idea but Mrs. Pendergrast wonders who will pay for it, and that they don't have sufficient resources to "erect walls for a bunch of savages" (p. 263). The chancellor takes a vote. The only one who votes yes is Mr. Lowe. The four argue with Mr. Lowe about peace and the value of their own lives over those of the Aven'ei. Vaela leaves, angry.

My comments: A wall? I don't know how long trump (lower case t for his name is not a typo) has been talking about a wall. I don't know when Drake came up with this part of her novel. Timing is unfortunate, but the idea... THE IDEA of a wall... introduced to young readers as a solution, delivered by the wealthy--in this case, Vaela Sun of the East Nation of the Spire--to the "uncivilized" peoples of the Continent... it reeks, Ms. Drake! Nobody in the novel says "that's messed up." This idea, of this wall, is put forth, uncritically.

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Vaela waits for the Chancellor to make arrangements for her to return to the Continent.

Chapter Thirty

Vaela reunites with Noro and tells him the Spire is not coming to help.

Chapter Thirty-One

Vaela settles back into her cottage and working on the farm but gets into an argument with Shoshi (he owns the farm and is one of the village leaders). He calls her a "takaharu" and tells her to leave and never return.

Vaela tells Yuki what happened and what he called her. The word "takaharu" means someone who is promiscuous, wanton, and revels in the sexual company of the enemy. Yuki thinks Vaela should tell Noro of this slander of her honor, but Vaela dismisses that idea, saying "Oh, honestly, you Aven'ei! My honor is intact."

Chapter Thirty-Two

Noro tells Vaela that it was the Aven'ei that started this war with the Topi, when the Aven'ei thought it would be an easy thing to take land from the Topi. He says they didn't anticipate "what they would become."

My comments: What were they before? Peaceful? Why did the Aven'ei think they could easily take the land? Did they view the Topi as child-like? Primitive?

Chapter Thirty-Three

The Aven'ei have gathered and are making ready for war. One evening, Yuki sings a song about a battle at Sana-Zo. The group talks about their final stand happening at the Southern Vale where they've gathered. After the battle, she says, only the Topi will be left to sing about the battle (p. 289):

My comments: Native people depicted as animal-like... If you're a regular reader of AICL, you know that happens a lot. If you have a copy of Little House on the Prairie, pull it out and read it. See how many ways Wilder depicts Native people as animal-like. Of course, that depiction is unacceptable.

On the third day at Southern Vale, the Topi "swarm" and "look like ants" as they fill the Vale. There are eight thousand of them, and only four thousand of the Aven'ei. Vaela hears drums again, along with "the clamoring insect noise of the Topi" (p. 293). The battles begin. Vaela and Noro are separated.

My comments: Here, Drake returns to an earlier characterization of the Topi as being ants. This time, though, she adds that they swarm and make insect noises. Need I say why this is offensive?

Chapter Thirty-Four

Gory fighting begins. Vaela kills a Topi man. She's repulsed by it but wants to do it again. She comes across a Topi whose intestines are spread across his belly. She kills him out of mercy. She looks up and sees another, a few feet away. He has yellow face paint and is grinning at her. She throws two knives at him, turns, and runs. He chases her, grabs her hair, throws her down. He snarls at her and chokes her. Her hands drop to her side, she finds another knife and starts stabbing him. He throws her down and just as he is about to strike her with his axe, Shoshi arrives and kills him. She turns, kills another Topi. Vaela and Shoshi stand together, looking across the field. Most Aven'ei are dead. There are still many Topi. She hears a buzz, looks up, and sees twelve heli-planes. The Spire has come, after all.

My comments: I'm at the end of my patience with this chapter-by-chapter read. What comes to mind each time I read that is the helicopter scene from Apocalypse Now, where they American forces blast Ride of the Valkyries.

Chapter Thirty-Five

The heli-planes hover low, over the field of battle. From one, an amplified voice booms, telling them to cease fighting, to cease the war, to stop, or they will be killed. The fighting doesn't stop, so, the men in the heli-planes start shooting. Topi men fall, "by the hundreds" (p. 305). The fighting stops. Some Topi howl at the heli-planes. The voice booms again, telling them to return to their own territories and not to pass onto the other's realm again. The Topi move westward; the Aven'ei move to the east.

The voice, Vaela realizes, is Mr. Lowe. It booms again, asking her to come to the heli-plane. Once there, she says she doesn't know what to say. He tells her she said all that needed saying, back at the Chancellory. The West chose to act alone, which led to a dissolution of the Spire. Mr. Lowe tells Vaela they (the West) will build the wall that she suggested. The war is over. He (Mr. West) will see to it.

Vaela reunites with Noro. He says it is time to bury the dead and help the wounded. She tells him they can live a life now, without war. He says "we shall see" and she replies (p. 312):

The story ends.

My comments: White saviors abound! In booming voices they tell those two warring peoples to.... go to their rooms. And, of course, they do as they're told! And just to make sure they don't get into any more fights, those white saviors are going to erect a wall to keep them apart. Those booming White voices will make sure peace reigns.

----

Moving out of italics, now, for some background information and closing thoughts on Kiera Drake's The Continent. As noted at the start of this page, the release for the book was postponed so the author could revisit it and make revisions. Prior to that announcement, there had been a lot of incisive discussion of the book on Twitter.

Drake responded to it on November 5, 2016. Here's the first paragraph of her response:

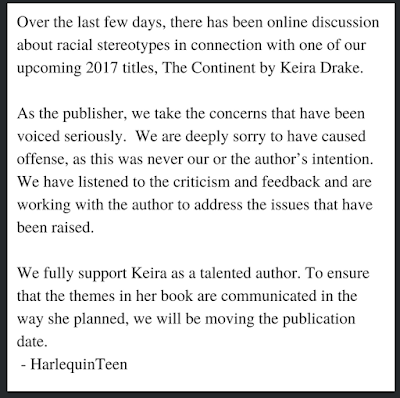

That same day, Halequin Teen posted this notice at their Tumblr page:

The assumption is that the book can be revised.

Is that possible? What would Drake change? In her response on November 5, she wrote:

Elsewhere on her site, there's a description of the book:

She could rewrite parts of the story so that someone says WTF are you doing thinking of these people as insects right away when Vaela first thinks of the Topi as ants, but who would do that? And what would it do to the rest of the story? It seems to me it would need a massive rewrite.

Drake may have set out to write a book about social responsibility, the nature of peace and violence, the value and danger of nationalism, but again, who is the audience? As I said above, I seriously doubt that she ever thought of a Native reader. If we add Native readers to the audience, what do they have to endure so that all the other readers discern Drake's themes? Yes, they could set the book down. They don't have to read it. Or... do they? What if it is assigned in school? Given the state of the world, teachers might think it the perfect novel to discuss what is happening in so many places.

I might be back with more thoughts, later. I'll certainly be back to fix typos and formatting errors I've missed, or clarify thoughts that--on a second or third read--need work. I may be back to write about the Discussion Questions that are at the end of the book. They were not in my ARC, but colleagues who have an ARC with the questions sent them to me.

______

See:

Justina Ireland's The Continent, Carve the Mark, and the Dark Skinned Aggressor

______

Update on Feb 1, 2016, at 8:45 AM:

I've learned that there was more discussion of the book on January 23rd. It prompted Drake to respond. Here's part of what she said:

Kiera Drake's The Continent was slated for release in January of 2017 from Harlequin Teen.

Questions from readers, however, prompted Harlequin Teen to postpone it. They didn't say they were canceling it. Just postponing it, which means they are trying to... fix it.

Can Drake revise The Continent so that it will, eventually, be released?

My answer: no.

I have an arc (advanced reader copy). I hope my review of that ARC is useful to the author, her editor, her publisher, and anyone else who is writing, editing, reviewing, or otherwise working with a book that depicts Native people.

Let's start with the synopsis:

"Have we really come so far, when a tour of the Continent is so desirable a thing? We've traded our swords for treaties, our daggers for promises--but our thirst for violence has never been quelled. And that's the crux of it: it can't be quelled. It's human nature."

For her sixteenth birthday, Vaela Sun receives the most coveted gift in all the Spire--a trip to the Continent. It seems an unlikely destination for a holiday: a cold, desolate land where two "uncivilized" nations remain perpetually locked in combat. Most citizens lucky enough to tour the Continent do so to observe the spectacle and violence of war, a thing long banished in the Spire. For Vaela--a talented apprentice cartographer--the journey is a dream come true: a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity to improve upon the maps she's drawn of this vast, frozen land.

But Vaela's dream all too quickly turns to a nightmare as the journey brings her face-to-face with the brutal reality of a war she's only read about. Observing from the safety of a heli-plane, Vaela is forever changed by the bloody battle waging far beneath her. And when a tragic accident leaves her stranded on the Continent, Vaela finds herself much closer to danger than she'd ever imagined. Starving, alone and lost in the middle of a war zone, Vaela must try to find a way home--but first, she must survive.During the course of the story, we'll learn that the Spire is comprised of four nations: the West, the East, the South, and the North.

Note: For each chapter below, summary is in plain text; my comments are in italics.

Chapter One

Chapter one opens with Vaela Sun's 16th birthday party in an ornate place in the Spire (a hundred million other people live there, too). Vaela has received three gifts from her parents. One is a ruby pendant on a gold chain that brings out the gold color of her hair. The second one is an elegantly framed map of the Continent that she drew based on her studies (she's a cartographer). The third gift is an official certificate of travel to the Continent. Trips to the Continent are very rare. There are only ten tours in a year, and only six guests on each tour.

My comments: Clearly, these are the most affluent people in this place called "the Spire." The name of the place embodies privilege. These two families are at the very top of that privilege.

Vaela and her parents dine with the Shaw's, who are highly placed in the Spire and used their influence to make the trip possible. At dinner, Vaela's father (Mr. Sun) and Mr. Shaw have this exchange (p. 15):

"Have you any thoughts, Mr. Shaw, about the natives on the Continent? I expect we shall see a good deal of fighting during our tour."

"I find them fascinating," says Mr. Shaw, leaning forward. I'm not as well-read on the natives as my boy Aaden here, but I think I favor the Topi. Seem a red-blooded sort--aggressive and primitive, they say."

"They are a popular favorite, to be sure," my father says. "Much more fearsome than the Aven'ei. I take no preference myself. But I admit, it will be interesting to see them at battle."My comments: Prior to reading this book, I knew that other people who had read the ARC had identified the Topi as being representative of the Hopi Nation, and the Aven'ei as Japanese. My grandfather (now deceased) was Hopi, born and raised at one of the villages in Arizona.

These wealthy white people, speaking of the Topi/Hopi as they do, is revolting. Native people, for these wealthy white people, are entertainment. When she wrote this book, did the author imagine that Native teens might read it?

Vaela's mom (Mrs. Sun) was hoping they wouldn't see any bloodshed, but Aaden Shaw asks if there's any other reason to go to the Continent. Though there are spectacular landscapes, he says (p. 15),

"Let's be honest--it's not the scenery that has every citizen in the Spire clamoring to see the Continent. It's the war."Mrs. Sun says she's not interested in seeing "natives slaughter one another" and Aaden presses her, asking her if she is prepared for it, because that is exactly what they will see. Mrs. Shaw says (p. 15):

"They've been railing at each other for centuries. I've never understood the fascination with it, myself. I'm right there with you, Mrs. Sun."My comments: Did you take that idea--that these two peoples on the Continent have been at constant, bloody, war with each other for centuries--as fact? If so, I think it reflects the degree to which you've been taught to think about those who are labeled as primitive, less-than-human other.

Mr. Sun and Mr. Shaw talk about how, from the safety of the heli-plane, they can observe war. Mr. Shaw says (p. 16):

"We take for granted that the Spire is a place without such primitive hostilities--that we have transcended the ways of war in favor of peace and negotiation. To see the Topi and the Aven'ei in conflict is to look into our past--and to appreciate how far we have come."Aaden wishes he could be on the ground and see the fighting up close, but Mr. Shaw prefers a safe distance from arrows and hatchets. Mrs. Sun thinks it is a "dreadful shame" they've not been able to sort out their differences, and Mrs. Shaw rolls her eyes (p. 16):

"I say let them kill each other. One day they'll figure out that war suits no one, or else they'll drive themselves to extinction. Either way, it makes no difference to me."Mrs. Sun reminds them that they are people, but Mrs. Shaw says they're people without good sense to know there are civilized ways to solve disagreements. Mr. Shaw relies:

"Before the Four Nations united to become the Spire, the people of our own lands were just as brutal, ever locked in some conflict or another. And see how far we have come? There may be hope yet for the Topi and the Aven'ei."Later, Vaela's mother asks her if she'll be all right with the violence she'll see. Vaela replies (p. 17):

It's what they do Mother. You oughtn't be so concerned. I know what to expect--we've all read the histories. The natives fight, and fight, and fight some more. Over land or territory or whatever it is--I've never quite understood--the war goes on and on. It never changes."My comments: This idea--of using people--to measure ones own progress towards "civilization" is more than just a story. At the 1893 World Columbian Exposition in Chicago, exhibits featured living Native peoples. The goal was to show fair-goers different evolutionary stages that placed Native peoples at the savage end of the exhibit, and white people at the other. Another example of using Native people as an exhibit was Ishi.

Chapter Two

The Shaws and the Suns board the plane. Mrs. Shaw is surprised with the small windows. Aaden tells her (p. 25):

"Don't worry, they're big enough. I expect you won't have any trouble watching the Topi chop the Aven'ei to pieces."Mrs. Shaw looks at Mr. Shaw. She says Aaden's vulgarity is his fault, for giving him "all those books about the Continent."

The plane takes off. Later, looking out a window, Aaden sees four natives. Mrs. Shaw is thrilled and asks if they're Aven'ei or Topi (p. 31):

"They're Aven'ei," Aaden says. "The Topi don't live this far south or east. In any case, you can tell from their clothing--see how everything is sort of mute and fitted? The Topi are more ostentatious--they wear brighter colors, fringed sleeves, bone helmets--that sort of thing."Mrs. Shaw thinks he's kidding about the helmets, but he says (p. 32):

"What better way to antagonize the Aven'ei than by flaunting the bones of their fallen comrades?"Mrs. Shaw goes on, saying that the Topi are vulgar and warmongering. She heard from a Mrs. Galfeather, that (p. 32-33):

"...there's nothing to the Topi but bloodlust. That's precisely the word she used: bloodlust. She says we know nothing else about them because there's naught else to know, and that they've bullied the Aven'ei for eons."Aaden responds that they're not bullies but is interrupted by Mr. Shaw, who has noticed what he thinks are flags hanging from a bridge. They peer down and realize they're not flags, but bodies. Vaela watches... (p. 33):

One of the strips swivels on its cable, and as it turns, I see the rotted face of a Topi warrior, his bone helmet shattered on one side, his arms bound tightly at the wrists."My comments: Bloodlust. An echo of "blood thirsty" Indians.

Chapter Three

Everyone is unsettled by what they saw. Vaela tells her dad she's fine. She thinks (p. 34):

The war between the natives is the stuff of legend--isn't it only natural to be curious about the morbid truth of things? Perhaps Aaden was right when he said that everyone has some interest in the conflict between the Topi and the Aven'ei--though my mother seems to be a rare exception to this rule.

I think the lot of us were simply unprepared to see anything macabre at that moment; we were so distracted and enthralled by our first view of the landscape, marveling at the unexpected appearance of the Aven'ei, and then... the bodies. Decayed and frightening and real. Unexpected.They all sit quietly, pretending not to be bothered. Vaela thinks it is easier to pretend a disinterest, rather than to admit how disturbing it was to see those bodies. Later, Aaden and Vaela talk about their safety at the Spire being a luxury they've earned after many centuries during which the Four Nations were at war. Aaden says (p. 36):

But have we really come so far, when a tour of the Continent is a desirable thing? We've traded our swords for treaties, our daggers for promises--but our thirst for violence has never been quelled. And that's the crux of it: it can't be quelled.Vaela's dad disagrees, saying that human nature compels them to seek peace, as they did in the Spire. The desire to see the natives at war on the Continent, he says, is just curiosity. Eventually they get to Ivanel, an island, which is their destination. Like their home at the Spire, the rooms at Ivanel are opulent. Everyone settles in for the night.

My comments: Aaden's remarks about war and violence as part of the human condition... what to make of that?

Chapter Four

The plan is an airplane tour of the Continent. The steward of Ivanel is their tour guide, pointing out geography, where the fights are taking place, and that of the land masses of their planet, the Continent is the least populated. Its population is in decline due to warfare. They fly over an Aven'ei town, and then (p. 47):

Before long, the plane is headed north, and we fly over an expansive network of Topi villages. The architecture is different from that of the Aven'ei: cruder harsher, yet terribly formidible, even in the frozen, icy territory the Topi call home. The little towns, too, are much closer together than Aven'ei villages; I am reminded of an ant colony, with many chambers all connected together, working to support a single purpose.My comments: The description of the Topi villages confirms that they're based on the Hopi people. The Hopis in Arizona and the Pueblos in New Mexico are related. We're descendants of what is commonly called "cliff dwellers." Here's an aerial photo that sounds precisely like what Vaela is describing:

Pueblo Bonito is in Chaco Canyon. It is one of many sites like that, in the Southwest. For a long time, the National Park Service called them homes of the Anasazi--who had disappeared--but today, that error is gone. These are all now regarded as homes of Ancestral Puebloans. Vaela, and perhaps Kiera Drake, look upon them and thinks of ants. Insects. Need I say how offensive that is?

The plane gets low enough for Vaela to see the villagers, who are "singularly dark of hair, with beautiful bronzed skin" (p. 47).

My comments: That's one of the (many) passages that needed some work. The Topi village is in the icy, frozen north. How, I wonder, can she see the skin color? Later we're going to read about their clothing for this climate.

Aaden is drawn to the buildings, exclaiming (p. 47):

"Look at the paint! It must be sleet and ice nearly all year round, yet the buildings are blood red, sunshine yellow--incredible!"The tour continues. They come upon a clearing where a battle is happening. Vaela looks out the window and is taken by the blood, everywhere, on the stark white of the land. Topi men decapitate an Aven'ei man, and then hurl the severed head up towards the plane.

My comments: Though the amount of space Drake gives to the scene is just over a page in length, her description makes it loom large. It feels gratuitous, too. Intended, I think, for us to remember how brutal war is--but especially how brutal the Topi are.

Chapter Five

Back at Ivanel, Vaela grasps the violence in a way she had not, before. She understands the difference between spectacle and death. Rather than go up in the plane again, Vaela and Aaden will go on a walking tour, led by the steward. His name is Mr. Cloud. He is a Westerner and has "beautiful dark skin" and "blue eyes so pale they are nearly white" (p. 55). Aaden and Vaela talk about the battle. Recalling history she says (p. 59):

The whole thing was dreadful. And to think, all those years ago, each was offered a place as a nation of the Spire if only their quarrels could be set aside. But they chose dissension. They chose death and blood and perpetual hostility. Why?Aaden tells her that the Aven'ei wanted to unite with the Spire but the Topi did not (p. 59):

"It was the Topi who refused--they wanted nothing to do with our people from the very first; we were never able to establish even the simplest trade with them." He scuffs his foot along the side of the rock and shakes his head. "It was different with the Aven'ei. They traded peacefully for decades with the East and the West--right up until the Spire was formed."Vaela wonders what the Aven'ei could possibly have, that the people of the Spire would want. Aaden chides her but she goes on, saying they are such a primitive culture. Aaden tells her that all things aren't measured in gold, that it was Aven'ei art and culture that Spire people desired. He reminds her of all the things in the Spire that are clearly influenced by Aven'ei aesthetic. Vaela wonders what the Aven'ei might have received in trade with the Spire. Weapons, she wonders, that might help them fight? Aaden tells her that the Aven'ei adopted the language of the Spire.

He also tells her that when the Continent was discovered 270 years ago, the Four Nations made a treaty amongst themselves that prohibited them from giving weapons to anyone on the Continent. There was trade, however, for a while. The East got lumber from the Aven'ei, and gave the Aven'ei agricultural wealth (crops and cattle). Vaela wonders why the Aven'ei didn't join the Four Nations. Aaden tells her that part of the treaty said that, in order to join, they would have to stop being a warring country. If they did that, the Topi would massacre them.

My comment: In each passage about the Topi and the Aven'ei, we see more and more that of the two, it is the Topi who are most primitive.

Chapter Six

The next day, the group gets on the plane again for another tour. Something goes wrong. Vaela's dad puts her in a safety pod. The plane crashes.

Chapter Seven

The pod lands in snow. After the third day, Vaela sets off, hoping to get to Avanel. At the end of the chapter, she's exhausted. Sitting against a tree, she hears what she thinks is the rescue plane.

Chapter Eight

Vaela gets up and runs towards the sound, then to a field. At the far end, she sees "a Topi warrior" bent over in the snow, a hatchet and dead squirrels beside him. He doesn't see her, so she decides to run into the field and wave at the plane. She does, but another Topi does see her. He's got red and yellow paint on his face and a quiver of arrows on his back. "The warrior's expression" is one of curiosity, not fierce. He calls to the other one. She runs, an arrow whizzes past her. She falls. He catches her, ties her hands together, rolls her over onto her back and looks into her face. His breath reeks of fish and decay as he speaks to her. The other warrior joins them. One jabs an arrow into her thigh. He hits her and she passes out.

My comments: Drake's use of "warrior" when she could have said "man" adds to the overall depiction of the Topi as warlike. That first guy? He was hunting. We don't know about the second one. But having his breath smell of decay... Drake is slowly but surely making the Topi out to be less than human.

Chapter Nine

Vaela comes to. She's on the ground on her back. The first Topi warrior she saw is with her. He grins at her; she notes his teeth, "blackened by whatever root he is chewing" (p. 88). He gives her some meat and berries. The other one returns later. Using a knife he draws a map in the dirt. She shows him where the Spire is.

Evening comes and the two men drink, "becoming increasingly boisterous" (p. 91). The first one finally passes out. The second one, however, yanks her to her feet and pulls her to him. There's a sticky white substance at the corners of his mouth. He buries his face in her hair and then starts kissing her her face and neck. She knows his intentions are "lustful." Suddenly, he falls away, a knife embedded in his neck. Another man, clad head to toe, in black. In the firelight she sees his "high cheekbones, dark almond-shaped eyes that slope gently upward at the corners, full lips" (p. 94). He speaks to her, in English.

My comments: Ah... the Drunken Indian stereotype. This drunk Topi, however, goes further. He's going to rape this blond haired white woman. This is SUCH A TROPE. Some stores have rows of romance novels with a white woman on the cover, in the arms of an Indian man. She might be struggling; she might not be. He is usually depicted as handsome.

Drake's menacing Native man is more like what we see in children's books. Like... this page in The Matchlock Gun:

Or in this scene from the television production of Little House on the Prairie (the part where they approach Ma is at the 1:45 mark, and again, at the 2:30 mark):

Here's a screen cap from the 2:10 mark:

Chapter Ten

Hearing English spoken to her is a healing ointment on her heart. He asks where she is from. She tells him she's from the Spire (p. 96):

His mouth opens slightly and his dark brows rise up an inch or so. "You come from the Nations Beyond the Sea." It is not so much a question as a realization.Their conversation continues. She tells him she was on a tour in the heli-plane. He wonders what that is, she tells him, and he tells her they call them anzibatu, or, skyships. He asks her why she was on a tour, saying "you come to watch us [...] like animals in a menagerie?" He wonders why they don't interfere in their fighting. She tells him their fighting is a curiosity, regrets saying it, and tries to explain that it is complicated. He ends the conversation telling her they'll leave in the morning. She asks where he intends to take her. He responds that she isn't a prisoner and can go with him if she wants to, or, stay where they are. Vaela asks him what is name is; he tells her he is called Noro. She thanks him for saving her life.

My comments: Another trope! In children's books about European arrival on what came to be known as the American continent, Native people are shown as being in awe of Europeans.

A small point, but annoying nonetheless: As Aaden noted in chapter five, the Aven'ei adopted English. I suppose Drake wrote that into the story so that Vaela and Noro could easily communicate, but some of the logic of words/concepts he knows (and doesn't know) feels inconsistent to me. He doesn't know the word heli-plane but does know menagerie (and later, "propriety" but doesn't know "technology").

Last point: Damsel's in distress, saved by a man, are annoying. Also annoying are female characters who run, trip, and are caught by bad guys. That happened in chapter five when Vaela was running away from the Topi man.

The next day, Noro thinks he should tend to Vaela's wounded thigh, but she's uneasy with having him touch her or see her bare leg. She relents, he cleans and bandages the wound, and she tells him this is the second time he's saved her. They set off.

That evening, Noro asks if other people in the Spire look like Vaela, with her "golden hair" and "eyes like the leaves of an evergreen" (p. 105). She tells him that the people in the West are dark-skinned with pale blue eyes, those in the North have pale skin and white hair, those in the South are olive-skinned with dark hair, and those in the East (where she is from) are often pale, with blue or green eyes.

My comments: Another trope! Time and again in children's books, writers depict Native people as in awe of blonde--or sometimes red--hair.

Chapter Eleven

Vaela is getting sick. Towards the end of the chapter, Noro has to carry her for awhile. He wants to take her to a healer when they get to his village but she's afraid of what that healer will do (leeches are one possibility). She insists that Noro take her to the village leaders first. He agrees. They arrive at the village.

Chapter Twelve

As they walk through the village, Vaela is surprised and impressed at their rich culture. She meets Noro's ten-year-old brother, Keiji. In Noro's cottage, she notices a tapestry on the wall, and a carved bookcase full of books. She learns that Noro is one of the few assassins they have. They "eliminate Topi leaders." Without the assassins, "the Topi would have wiped us from the Continent long ago" (p. 125).

My comments: Earlier, I noted that the author (Kiera Drake) was, as the story unfolded, drawing a distinction between the Topi and the Aven'ei. The description of the tapestry and books add a lot. They are definitely not "uncivilized."

Vaela and Noro go to the meeting with the village leaders. They deny her request to be taken back to Ivanel because it is dangerous to try to be on the sea during this part of the year, and, because they're at war. Noro takes Vaela to Eno's (the healer) cottage.

Chapter Thirteen

Vaela spends several weeks under the care of Eno. Keiji visits but Noro does not.

Chapter Fourteen

When she's well, Keiji takes her to her own cottage. It is furnished much like Keiji and Noro's. Sofa, bookshelf, books. She looks around the main room, the kitchen, her bedroom, and a room with a bash basin and a chamber pot. Later she goes to visit Noro, who tells her the leaders want to see her again, to assign her a job. She tells Noro about "the Lonely Islands" (p. 148) of the Spire. Citizens who don't want to work are "invited" to relocate to that place. Some choose to go, others are sent.

Chapter Fifteen

Vaela begins work as a field hand, scooping and hauling cow manure. Noro gave her some money to use until she gets paid. She goes to the market, where an old woman remarks on her gold hair, with its "strings of sunshine." The woman offers Vaela three, then four, then five oka (coins) for it but Vaela says no. Vaela meets a young woman, Yuki Sanzo (they're going to become good friends).

My comments: the fascination/value again of blonde hair...

Yuki tells her the war is because of a debt, and that now, the Topi (p. 159):

"understand the riches of the south. The fertility of our soil, the safety of our shoes. The agriculture we have cultivated. They love the north, but desire what the north cannot deliver. And so they seek to take it from us, here in the south and east."Vaela tells Yuki that on the Spire, they found a way to share resources and that perhaps, someday, the Topi and Aven'ei will do that, too.

My comments: This depiction of the Topi as hunter/gatherers who don't know how to farm is common, in fiction, nonfiction, and textbooks, too. It is an error, especially given that the Topi are based on the Hopi, who for thousands of years, cultivated corn in the southwest. Doing that required sophisticated irrigation systems. This is well-described in Roxane Dunbar-Ortiz's book (An Indigenous Peoples History of the U.S.) This widespread misrepresentation lays the groundwork for justifying occupation and colonization of Native lands.

Chapter Sixteen

Vaela does her work, and thinks about how she could make a map that the Aven'ei could use in their war against the Topi.

Chapter Seventeen

On a visit, Yuki realizes that Vaela doesn't know how to take care of herself or cook, either. She teaches her. Noro visits; Vaela tells him she wants to visit the council about improvements in the village. Specifically, she tells him about toilets and how they work. He's disgusted with the idea of having a privy inside the house.

Chapter Eighteen

Vaela tells Yuki the villagers give her odd looks. Yuki tells her they're just wary of her. Yuki tells her she needs to have a knife with her at all times because the Continent is not the Spire. Vaela thinks the Topi wouldn't come to the village. Yuki isn't sure of anything.

Chapter Nineteen

Keiji starts teaching Vaela how to fight; Noro calls Vaela "miyake" which means "my love."

Chapter Twenty

Noro reports that there are Topi nearby and asks Vaela to draw a map of where they are; they take the map to the leaders. Noro gives Vaela a set of throwing knives.

Chapter Twenty-One

When Noro is teaching Vaela how to use a knife to kill someone, quickly, and quietly. Vaela asks if that is the technique that Noro used on the Topi who found her after the crash. He nods; she says that the Topi was kind to her, that he gave her food. Noro gets angry that she grieves for the Topi, and tells her she cannot look upon them as men. They are the enemy. She tells him the Topi are people, too. Yuki is angry at her, too, telling her that the Topi might put her head on a pike. Vaela counters that the Aven'ei are brutal, too, and recounts the bodies they saw from the plane. Another person who is with them, Takashi, says that Vaela makes a valid point. Yuki and Takashi start arguing. Vaela tries to get them to stop, and Yuki tells her that she is, and will always be, an outsider.

My comments: in that passage and before, Vaela seems to be wanting to help. That, however, is another problem with how she is developed. She's a white character, entering a place of Native and People of Color, attempting to improve their lives--according to her standards. This a white savior.

Chapter Twenty-Two

The Topi come into the village. Noro goes out to fight, telling Vaela to stay in the bedroom with her knives. But later, she starts thinking she can at least kill one Topi (p. 216):

If I were to try and fight, I would almost surely die. But I might kill one. One Topi whose thirst for blood cannot be quenched except in death.She goes outside. As she walks she hears rhythmic pounding. She remembers Yuki talking about the drums of war. She sees a Topi and maps out a route to position herself. She notices he's got his eyes fixed on someone that she recognizes to be Keiji. He's struck in the neck. She rushes to him. Noro and another assassin get there, too. Noro goes looking for the Topi who shot Keiji. Vaela thinks the Topi archer "does not have long to live."

My comments: When I started this chapter-by-chapter read, I noted that a Native reader--and especially one who is Hopi--would have a different experience than, perhaps, most others who read these passages about killing. To make them as brutal as possible, this Topi is firing at a child (remember, Keiji is only ten years old).

Chapter Twenty-Three

They take Keiji to a healer. Noro arrives shortly. Vaela asks if he killed the Topi archer and replies "good" when he says he did. Noro tells her she would not have killed a Topi. Instead, she would have been killed, and if not that, she'd have been "captured, raped and beaten--kept to be used by any savage who wanted you" (p. 225).

My comments: On the heels of the Topi warrior who shot a child, Drake puts forth a scenario where a "savage" rapes, beats, and uses the blonde as he wishes.

Vaela tells Noro she wants to return to the Spire to get help. Noro tells her they already know what is happening, that they've known for over 200 years and not intervened. Vaela is sure she can persuade them. She promises she'll return (p. 229):

I give you my word I will return. And when I do, I will bring peace to the Continent. One way or another, I will ring peace.

My comments: Again, Drake depicts her main character as a white savior.

Chapter Twenty-Four

The village leaders approve of Vaela's plan to return to the Spire. Noro will take her to Ivanel.

Chapter Twenty-Five

Vaela and Noro arrive on Ivanel. He's impressed with the building and the glass windows. She tells him it has other things, too, like an indoor swimming pool, racquet courts, cedar saunas, and toilets. Soon after that, they say their good-byes. Noro leaves Ivanel.

My comments: that scene strikes me as tone deaf and heartless. Didn't they just spend hours with Keiji, worried for his life? I guess out-of-sight, out-of-mind...

Chapter Twenty-Six

Valea plans for her return to the Spire where she will try to persuade the Heads of State to intervene.

Chapter Twenty-Seven

Vaela arrives at her home at the Spire.

Chapter Twenty-Eight

Vaela goes to the Chancellery for her meeting with the sweet-faced Mr. Lowe of the West who has dark skin and pale eyes, Mr. Wey of the East who is a scholarly man in spectacles, Mr. Chamberlain of the South, who is sickly looking, has a slender mustache, and watery eyes, and Mrs. Pendergrast of the North who looks like she spent her life sucking on sour candy. Vaela notices that Mr. Lowe and Mrs. Pendergrast avoid each other.

Mr. Lowe thinks the Aven'ei could be relocated to the Spire. Mrs. Pendergrast thinks they're uncivilized and should not be brought there. Vaela tells them the Aven'ei are not uncivilized, but that they wouldn't leave their homes. Mr. Lowe asks her what she wants, then, if not to help them relocate.

Vaela says she wants the Spire to build a wall between the Aven'ei and the Topi. Mr. Lowe thinks it a good idea but Mrs. Pendergrast wonders who will pay for it, and that they don't have sufficient resources to "erect walls for a bunch of savages" (p. 263). The chancellor takes a vote. The only one who votes yes is Mr. Lowe. The four argue with Mr. Lowe about peace and the value of their own lives over those of the Aven'ei. Vaela leaves, angry.

My comments: A wall? I don't know how long trump (lower case t for his name is not a typo) has been talking about a wall. I don't know when Drake came up with this part of her novel. Timing is unfortunate, but the idea... THE IDEA of a wall... introduced to young readers as a solution, delivered by the wealthy--in this case, Vaela Sun of the East Nation of the Spire--to the "uncivilized" peoples of the Continent... it reeks, Ms. Drake! Nobody in the novel says "that's messed up." This idea, of this wall, is put forth, uncritically.

Chapter Twenty-Nine

Vaela waits for the Chancellor to make arrangements for her to return to the Continent.

Chapter Thirty

Vaela reunites with Noro and tells him the Spire is not coming to help.

Chapter Thirty-One

Vaela settles back into her cottage and working on the farm but gets into an argument with Shoshi (he owns the farm and is one of the village leaders). He calls her a "takaharu" and tells her to leave and never return.

Vaela tells Yuki what happened and what he called her. The word "takaharu" means someone who is promiscuous, wanton, and revels in the sexual company of the enemy. Yuki thinks Vaela should tell Noro of this slander of her honor, but Vaela dismisses that idea, saying "Oh, honestly, you Aven'ei! My honor is intact."

Chapter Thirty-Two

Noro tells Vaela that it was the Aven'ei that started this war with the Topi, when the Aven'ei thought it would be an easy thing to take land from the Topi. He says they didn't anticipate "what they would become."

My comments: What were they before? Peaceful? Why did the Aven'ei think they could easily take the land? Did they view the Topi as child-like? Primitive?

Chapter Thirty-Three

The Aven'ei have gathered and are making ready for war. One evening, Yuki sings a song about a battle at Sana-Zo. The group talks about their final stand happening at the Southern Vale where they've gathered. After the battle, she says, only the Topi will be left to sing about the battle (p. 289):

"They don't sing," Noro says. "They howl."They all laugh.

My comments: Native people depicted as animal-like... If you're a regular reader of AICL, you know that happens a lot. If you have a copy of Little House on the Prairie, pull it out and read it. See how many ways Wilder depicts Native people as animal-like. Of course, that depiction is unacceptable.

On the third day at Southern Vale, the Topi "swarm" and "look like ants" as they fill the Vale. There are eight thousand of them, and only four thousand of the Aven'ei. Vaela hears drums again, along with "the clamoring insect noise of the Topi" (p. 293). The battles begin. Vaela and Noro are separated.

My comments: Here, Drake returns to an earlier characterization of the Topi as being ants. This time, though, she adds that they swarm and make insect noises. Need I say why this is offensive?

Chapter Thirty-Four

Gory fighting begins. Vaela kills a Topi man. She's repulsed by it but wants to do it again. She comes across a Topi whose intestines are spread across his belly. She kills him out of mercy. She looks up and sees another, a few feet away. He has yellow face paint and is grinning at her. She throws two knives at him, turns, and runs. He chases her, grabs her hair, throws her down. He snarls at her and chokes her. Her hands drop to her side, she finds another knife and starts stabbing him. He throws her down and just as he is about to strike her with his axe, Shoshi arrives and kills him. She turns, kills another Topi. Vaela and Shoshi stand together, looking across the field. Most Aven'ei are dead. There are still many Topi. She hears a buzz, looks up, and sees twelve heli-planes. The Spire has come, after all.

My comments: I'm at the end of my patience with this chapter-by-chapter read. What comes to mind each time I read that is the helicopter scene from Apocalypse Now, where they American forces blast Ride of the Valkyries.

Chapter Thirty-Five

The heli-planes hover low, over the field of battle. From one, an amplified voice booms, telling them to cease fighting, to cease the war, to stop, or they will be killed. The fighting doesn't stop, so, the men in the heli-planes start shooting. Topi men fall, "by the hundreds" (p. 305). The fighting stops. Some Topi howl at the heli-planes. The voice booms again, telling them to return to their own territories and not to pass onto the other's realm again. The Topi move westward; the Aven'ei move to the east.

The voice, Vaela realizes, is Mr. Lowe. It booms again, asking her to come to the heli-plane. Once there, she says she doesn't know what to say. He tells her she said all that needed saying, back at the Chancellory. The West chose to act alone, which led to a dissolution of the Spire. Mr. Lowe tells Vaela they (the West) will build the wall that she suggested. The war is over. He (Mr. West) will see to it.

Vaela reunites with Noro. He says it is time to bury the dead and help the wounded. She tells him they can live a life now, without war. He says "we shall see" and she replies (p. 312):

It is done now," I say, gesturing up at the heli-planes. "The West has come to ensure peace. You need never wear the shadow of the itzatsune again."They kiss. She thinks that she knows peace, once again, for now, and that sometimes, now is enough.

The story ends.

My comments: White saviors abound! In booming voices they tell those two warring peoples to.... go to their rooms. And, of course, they do as they're told! And just to make sure they don't get into any more fights, those white saviors are going to erect a wall to keep them apart. Those booming White voices will make sure peace reigns.

----

Moving out of italics, now, for some background information and closing thoughts on Kiera Drake's The Continent. As noted at the start of this page, the release for the book was postponed so the author could revisit it and make revisions. Prior to that announcement, there had been a lot of incisive discussion of the book on Twitter.

Drake responded to it on November 5, 2016. Here's the first paragraph of her response:

I am saddened by the recent controversy on Twitter pertaining to THE CONTINENT. I abhor racism, sexism, gender-ism, or discrimination in any form, and am outspoken against it, so it was with great surprise and distress that I saw the comments being made about the book. I want everyone to know that I am listening, I am learning, and I am trying to address concerns about the novel as thoughtfully and responsibly as possible.On November 7, 2016, author Zoraida Córdova wrote An Open Letter on Fantasy World Building and Keira Drake's Apology.

That same day, Halequin Teen posted this notice at their Tumblr page:

The assumption is that the book can be revised.

Is that possible? What would Drake change? In her response on November 5, she wrote:

THE CONTINENT was written with a single theme in mind: the fact that privilege allows people to turn a blind eye to the suffering of others. It is not about a white savior, or one race vs. another, or any one group of people being superior to any other. Every nation, and every character in the book is flawed.Almost three months ago, Drake felt that Vaela is not a white savior. Has she changed her mind? Does my close read help her see that it is, indeed, a white savior story? Ironically, (to quote her words), she seems to be blind to the suffering of others. She seems to think that every nation and every character in her book is flawed. I wouldn't argue with that statement. It is the degree to which they're flawed, and the ability of readers to SEE them as flawed that is the problem. She herself doesn't seem to be able to see the white savior! It is right there on the last pages!

Elsewhere on her site, there's a description of the book:

Keira Drake‘s young adult fantasy, THE CONTINENT, is part action adventure, part allegory, and part against-the-odds survival story. Engaging with questions of social responsibility, the nature of peace and violence, and the value (and danger) of nationalism, Drake’s debut is as thought-provoking as it is fast-paced and surprising, a heart-pounding and heartbreaking story of strength and survival.Her story rests completely upon the idea that one of these peoples--the Topi (the Native people)--are utterly barbaric. They're animal like. They're insect like. None of that is effectively challenged by anyone in the story or by the author, either, in how any of the characters think. There is that one scene when Noro and Yuki are angry at her for trying to tell them the Topi aren't the only ones who are brutal, but overwhelmingly, Drake's characters think of them as less-than.

She could rewrite parts of the story so that someone says WTF are you doing thinking of these people as insects right away when Vaela first thinks of the Topi as ants, but who would do that? And what would it do to the rest of the story? It seems to me it would need a massive rewrite.

Drake may have set out to write a book about social responsibility, the nature of peace and violence, the value and danger of nationalism, but again, who is the audience? As I said above, I seriously doubt that she ever thought of a Native reader. If we add Native readers to the audience, what do they have to endure so that all the other readers discern Drake's themes? Yes, they could set the book down. They don't have to read it. Or... do they? What if it is assigned in school? Given the state of the world, teachers might think it the perfect novel to discuss what is happening in so many places.

I might be back with more thoughts, later. I'll certainly be back to fix typos and formatting errors I've missed, or clarify thoughts that--on a second or third read--need work. I may be back to write about the Discussion Questions that are at the end of the book. They were not in my ARC, but colleagues who have an ARC with the questions sent them to me.

______

See:

Justina Ireland's The Continent, Carve the Mark, and the Dark Skinned Aggressor

______

Update on Feb 1, 2016, at 8:45 AM:

I've learned that there was more discussion of the book on January 23rd. It prompted Drake to respond. Here's part of what she said:

While I cannot control what others may say, I can communicate to you here in very clear terms that I value criticism, have listened to all feedback concerning the book, and am working to address those concerns. I remain tremendously appreciative to those in the writing community who offered constructive insight, guidance, and feedback in regard to THE CONTINENT. I feel very blessed to have such an incredible network of friends, critics, readers, and industry professionals at my side, and am so grateful to Harlequin TEEN for allowing me the opportunity to revise before publication. I see with clarity that the comparisons drawn between the fictitious peoples of the book and those of existing cultures are valid and important, and, once again, wish to communicate how sorry I am that the original version of the book reflected these and other harmful representations.

Labels:

Kiera Drake,

The Continent

Thursday, June 16, 2016

A critical look at O'Dell's ISLAND OF THE BLUE DOLPHINS

Update on Sep 24, 2018: I (Debbie), shared this post on Twitter yesterday, because I was critiquing a young adult novel in which the author cited Island of the Blue Dolphins as a significant book from her childhood. Dr. Eve Tuck read my tweet, this post, and responded. Dr. Tuck is Aleut, and is an Education professor who has served as editor of NCTE's English Journal. See her article, Decolonization is not a metaphor, and her books, listed at her website. With her permission, I am adding her response to my tweet and article. They are at the bottom of this post.

~~~~~~~~~~

"A Critical Look at O'Dell's Island of the Blue Dolphins"

Debbie Reese (published here on June 16, 2016)

In his story,

O’Dell changes Juana Maria’s status to a twelve-year old girl named Karana. As

the story opens, Karana and her little brother Romo are digging roots when a ship

arrives. On board is a Russian captain named Orlov who has come with forty of

his (Aleut) men to hunt sea otter. Based on past experiences, Chief Chowig

(Karana’s father) and Orlov have a tense discussion about what the Ghalas-at

will receive in return for the otters that will be taken from the waters that

abut the island. Months later when Orlov readies to leave without holding up

his end of the bargain, a fight breaks out. Most of the men of Ghalas-at,

including Chowig, are killed. Two years later, the survivors are rescued. After

the rescue ship leaves the cove, Karana realizes Romo is not on board. She

jumps ship to stay with him and wait for another rescue ship. Soon after, wild

dogs kill Romo, and Karana is alone until her rescue.

Her years on the

island make survival a central theme of the story. During that time, she builds

several shelters, makes weapons that only men are supposed to make (according

to tribal traditions), finds food, fights wild dogs, befriends a large dog that

she thinks came to the island with the Russian ship and then when he dies,

tames a wild dog that she thinks was fathered by the large dog. She survives an

earthquake, a tsunami, and several harsh winter storms.

At the close of

the story, she is leaving the island. Based on the text, she has been there at

least four years. On page 162, the text reads that two years have passed since

the Aleuts had been on the island. At that point, Karana stopped counting the

passage of time. One spring, there is an earthquake. As she makes a new

shelter, she sees a ship and at first, she hides from the two men who come

ashore. She decides she wants to be with people again, and rushes down to the

cove but the canoe is gone. Two years pass and a ship returns. This time, she

doesn’t hide. When the ship leaves, she is on board with her dog and two caged

birds.

A few words about Scott O’Dell

Born in Los

Angeles, California in 1898, O’Dell died in 1989. He spent the first thirty

years of his adult life working in Hollywood as a cameraman and writer. In

1920, a California newspaper misprinted Odell Gabriel Scott’s name as Scott

O’Dell. Liking the misprint, Scott legally changed his name and from then on,

was known as Scott O’Dell. In 1947, he became the book editor for the Los Angeles Daily News (Payment, 2006).

In addition to his

writing, O’Dell spent time with his father on his orange grove ranch, where he

visited ranches of Spanish families of the Pomona Valley and listened to their

stories of the past. This led him to write three novels for adults, and a

history of California.

In 1957, O’Dell

published Country of the Sun: Southern

California, An Informal History and Guide. Therein, he references Helen

Hunt Jackson’s articles, published in 1882 in Century Magazine, about the mistreatment of the Cupeno Indians of

California. He also references her novel, Ramona,

published in 1884, saying her novel “had about the same impact as Uncle Tom’s Cabin. Overnight, the

country was aroused to the plight of the Southern California Indian” (p. 52). Country of the Sun includes two pages

about “The Lost Woman of San Nicolas Island”.

O’Dell developed

the story into a book-length manuscript and showed it to Maud Lovelace (author

of the Betsy-Tacy books). She persuaded him “that it was a book for children,

and a very good one” (Scott O’Dell, n.d.). Lovelace penned the biography for

O’Dell when he won the Newbery Medal for Island

of the Blue Dolphins. She concludes the biography with “Scott O’Dell’s life

brought him naturally a knowledge of Indians, dogs, and the ocean; and he was

born with an inability to keep from writing. So he gave us the moving legend of

Karana” (p. 108).

In his acceptance

speech, O’Dell referenced animal cruelty and forgiveness as themes that are

present in his book. He also spoke at length of Antonio Garra, a Cupeno Indian

man who, just before he was executed under bogus charges, said “I ask your

pardon for all my offenses, and I pardon you in return” (O’Dell, p. 103).

O’Dell went on to say that this man, of a peaceful tribe, is unknown to the

world because he was peaceful rather than “like Geronimo” (p. 103). Karana, he

said, belonged to a tribe like Garra’s. He concluded his speech saying that

Karana, before her people were killed, lived in a world where “everything lived

only to be exploited” but that she “made the change from that world” to “a new

and more meaningful world” because she learned that “we each must be an island

secure unto ourselves” where we “transgress our limits” in a “reverence for all

life” (p. 104).

Acclaim and Critiques of Island

of the Blue Dolphins

Island of the Blue Dolphins received

glowing reviews and went on to win the Newbery Award. It was made into a movie

in 1964 and has since been made into audio recordings several times. The

National Council of Teachers of English listed it on its “Books for You” in

1972, 1976, and 1988. In 1976, the Children’s Literature Association named it

one of the ten best American children’s books of the past 200 years (O’Dell,

1990). It is the subject of numerous amateur videos on YouTube and there are

volumes of lesson plans written for teachers. Over the years, the cover has

changed several times. As of this writing, it has 734 customer reviews on

Amazon.com. Thirty-three readers gave it one star, while over 600 gave it four or

five stars.

In 1990, Island of the Blue Dolphins was republished,

with illustrations rendered by Ted Lewin, and an introduction by Zena

Sutherland. A fiftieth anniversary edition was published in 2010, with a new

introduction by Lois Lowry. She showers O’Dell’s novel with praise, noting that

he “masterfully” brings the reader onto the island (O’Dell, 2010). In 2010, School Library Journal blogger Elizabeth

Bird listed it as one of the Top 100 Children’s Novels (Reese, 2010). In 2010,

the book was listed in second place on Amazon’s list of “Bestsellers in

Children’s Native American Books” (Reese, 2010).

In the academic

literature, Maher (1992) writes that Island

of the Blue Dolphins is a “counterwestern” that gives “voice to the

oppressed, to those who lost their lands and their cultures” (p. 216). Tarr

(1997) disagrees with that assessment, asserting that the reader’s uncritical

familiarity with stereotypical depictions of American Indians is the reason it

has fared so well. Moreover, Tarr (2002) writes that the stoic characterization

of Karana and her manner of speaking without contractions are stereotypical

Hollywood Indian depictions rather than one that might be called authentic. Placing