▼

Saturday, May 17, 2014

San Jose State University, College of Applied Sciences, School of Library and Information Science, recognizes Debbie Reese for Exemplary efforts to enhance equity and diversity

"According to her nomination form, she was the recipient of the 2013 Virginia Matthews Scholarship Award for her “sustained involvement in the American Indian community and her sustained commitment to American Indian concerns and initiatives.” Her award-winning blog, American Indians in Children’s Literature, shined the spotlight on the Arizona law that led to the recent shutdown of the Mexican American Studies Program in the Tucson Unified School District. According to the American Indian Library Association, Reese not only works with the Nambe community and “she strives to inform the dominant culture about issues facing Indian people today.” --Melissa Anderson, SJSU

Thursday, May 15, 2014

Another 'thank you' to Cynthia Leitich Smith

A few hours ago, my daughter called to tell me she'd finished her last exam of the semester. With joy and enthusiasm, she said she was finished with Year One of law school.

I was happy to hear her voice as she described that last exam and reflected on the year. I carried her joy through my day. And then, a hour ago, I was on Twitter when a colleague tweeted a photo from Cynthia Leitich Smith's Jingle Dancer. If you're a regular reader of AICL, you know that I talk about that book more than any other. It is the one I wish I'd had when my daughter was a three year old and dancing for the first time at home. Our dance, by the way, is like prayer. Not entertainment, and not performance. Prayer. Everyone helps get ready for that first dance. Smith depicts that in Jingle Dancer.

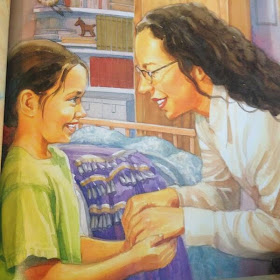

But the particular page that I'm thinking of right now is this one:

That is Jenna on the left. On the right is Jenna's cousin, Elizabeth. At that point in Smith's story, Jenna is visiting Elizabeth. Elizabeth can't be with Jenna on that special day. She's got a big case she's working on. You see, Elizabeth is a lawyer.

Need I say more about why that page is special to me today? Your book continues to give to me, Cyn. Thank you.

I was happy to hear her voice as she described that last exam and reflected on the year. I carried her joy through my day. And then, a hour ago, I was on Twitter when a colleague tweeted a photo from Cynthia Leitich Smith's Jingle Dancer. If you're a regular reader of AICL, you know that I talk about that book more than any other. It is the one I wish I'd had when my daughter was a three year old and dancing for the first time at home. Our dance, by the way, is like prayer. Not entertainment, and not performance. Prayer. Everyone helps get ready for that first dance. Smith depicts that in Jingle Dancer.

But the particular page that I'm thinking of right now is this one:

That is Jenna on the left. On the right is Jenna's cousin, Elizabeth. At that point in Smith's story, Jenna is visiting Elizabeth. Elizabeth can't be with Jenna on that special day. She's got a big case she's working on. You see, Elizabeth is a lawyer.

Need I say more about why that page is special to me today? Your book continues to give to me, Cyn. Thank you.

Wednesday, May 14, 2014

Why I Advocate for Books by Native Writers and Illustrators/Gallery of Native Writers and Illustrators

Editor's Note: Scroll down to see the photo gallery of Native writers and illustrators.

I spent an hour today in a twitter chat hosted by First Book. The chat was part of the We Need Diverse Books campaign.

In the chat I advocated for authors who are Native.

Right away--as usual--a white writer posed a question about white writers, asking the First Read host if authorship of a book matters.

Not surprisingly, First Book said that authorship does not matter. Diversity of characters is what they're after. That's the answer you get from, I'd guess, every publisher.

I persisted, though, because I do think it matters. Here's why:

Just about every book a kid picks up has white people in it. And, just about every book is written and illustrated by a white author or illustrator. For literally hundreds of years, white kids have seen themselves reflected in the books they read, and they've had the chance to see people who look like them as writers and illustrators of those books. By default, they've been able to see a possible-self. By default, they could imagine themselves as the writer or illustrator of that book. It may not have been a conscious thing, but it was the norm. The default. The air they breathe. Every day.

I want that for Native kids. I want them to see books written and illustrated by people who look like them. I want them to be able to think "Hmmm... I could be a writer, too, just like Cynthia Leitich Smith!" or "Hey! I could be an illustrator, too, just like S. D. Nelson!"

I understand that white authors and illustrators feel threatened by my advocacy, but my advocacy is for Native children who deserve the same affirmations white kids get all the time.

I'm closing this post with a tribute to Native writers and illustrators of books I've recommended on AICL. That tribute is photos of them. They are in no particular order. I'll keep adding to this gallery, because I don't have time right now to be comprehensive. I'll do my best, and I welcome you to write to me to let me know to add someone I've missed. Each person's tribe is beneath their name. If there are errors, I apologize, and please let me know.

American Indians in Children's Literature

presents

A Gallery of Native Writers and Illustrators

|

| Cynthia Leitich Smith Muscogee Creek Image source: Cynsations http://goo.gl/0wneBW |

|

| Michael Lacapa Apache, Hopi Image source: Northern Arizona Book Festival http://goo.gl/4POyCQ |

|

| Eric Gansworth Onondaga Image source: Milkweed http://goo.gl/6FqBTB |

|

| Nicola I. Campbell Nlel7kepmx, Nsilx and Metis Image source: The Word on the Street http://goo.gl/l284Ko |

|

| Tim Tingle Choctaw Image source: My Very Own Book http://goo.gl/4KRgwp |

|

| Virginia Driving Hawk Sneve Lakota Sioux Image source: Native Daughters http://goo.gl/1mCbDU |

|

| Richard Van Camp Dogrib Image Source: Zimbio http://goo.gl/Zg8TNR |

|

| Arigon Starr Kickapoo Image source: Starrwatcher Online http://goo.gl/hyLzhc |

|

| S.D. Nelson Standing Rock Sioux |

|

| Beverly Blacksheep Navajo |

|

| Simon Ortiz Acoma |

|

| Cheryl Savageau Abenaki |

|

| Donald Uluadluak Inuit |

|

| Jan Bourdeau Waboose Nishnawbe Ojibwe |

|

| Daniel Wilson Cherokee |

|

| Joy Harjo Mvskoke |

|

| Shonto Begay Navajo |

|

| Cheryl Minnema Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe |

|

| Wesley Ballinger Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe |

|

| Luci Tapahonso Navajo |

|

| Greg Rodgers Choctaw |

|

| Marcie Rendon White Earth Anishinabe |

|

| Ofelia Zepeda Tohono O'Odham |

|

| N. Scott Momaday Kiowa |

|

| Laura Tohe Navajo |

|

| Allan Sockabasin Passamaquoddy |

|

| Julie Flett Metis |

|

| Richard Wagamese Wabasseemoong Ojibway |

|

| Leslie Marmon Silko Laguna |

|

| Heid E. Erdrich Turtle Mountain Chippewa |

|

| Deborah Miranda Esselen |

|

| Anton Trueur Ojibwe |

|

| John Rombough Chipewyan Dene |

|

| James Welch Blackfeet/Gros Ventre |

|

| Tomson Highway Cree |

|

| George Littlechild Plains Cree |

Tuesday, May 13, 2014

Cheryl Minnema's HUNGRY JOHNNY

A significant component of the We Need Diverse Books campaign is regarding the authorship of books. For AICL, that means books written and illustrated by Native authors. In the midst of the We Need Diverse Books campaign, I received a copy of Hungry Johnny. Here's the cover:

The author of Hungry Johnny is Cheryl Minnema. She's Ojibwe, and so is the illustrator, Wesley Ballinger. And the story? It is about an Ojibwe kid. Named Johnny. Who is--as the title suggests--hungry!

When the book opens, Johnny is outside playing, but his tummy growls. He's hungry, and heads inside where his grandma is making wild rice. He spies that plate of sweet rolls on the table and makes a beeline for it, but she tells him "Bekaa, these are for the community feast." The word 'bekaa' is in bold on the page. It is one of several Ojibwe words in Minnema's book. Bekaa, by the way, means 'wait.'

As the cover demonstrates, Johnny lives in a modern home. His grandma, in jeans, sweater, and a ball cap, is at an electric stove, and as Johnny plods to another room, we see hardwood floors and photographs on the wall. When his grandmother tells him it is time to go, he leaps off the couch. He wants to eat, eat, eat! As they drive to the community center, he sings "I like to eat, eat, eat. I like to eat, eat, eat."

I've not said anything about a word that appears in the two paragraphs directly above this one. Community. There is a community feast at the community center. Such gatherings and spaces are common across the U.S. and Canada. It is one of the many ways that Native people maintain our traditions and relationships with each other.

At the center, Johnny has to wait again. An elder says a "very l-o-n-g prayer." Perfect! That is exactly what happens. As a kid, it seemed to me forever, too, waiting for elders to finish praying. But, wait we did, and so does Johnny. I gotta share a photo of that page:

See the elder's vest? That particular page highlights Ballinger's connections to his Ojibwe community. That is Ojibwe beadwork--the very kind that Minnema is known for! Here's a photo of some of her exquisite work:

Back to the story...

Elders eat first, so Johnny has to wait. His grandma waits with him, telling him to be patient. He wonders why she's not eating with the elders, and she explains she is a "baby elder" that is "too young to be old and too old to be young."

When Johnny and his grandma are finally at the table, he is crestfallen because the plate of rolls is empty. It is, however, a feast, and another plate of them is brought to the table. Just then, Johnny sees Katherine (an elder) arrive, and calls her over to take his seat. He isn't glum in calling to her. He understands that elders receive special treatment.

Course, this is a community with elders who pay attention to young ones, so, Katherine invites him to sit on her lap. Johnny finally gets his sweet roll.

There's a lot that I like about Hungry Johnny. The Ojibwe words, the teachings imparted, and, Ballinger's art. In 2000, Simms Taback won the Caldecott Medal for Joseph Had a Little Overcoat. I was teaching undergraduates that year in the College of Education. The Jewish students in my class pored over it, pointing to things in the illustrations that affirmed Jewish culture. I didn't notice them, but the students did, and it mattered to them a great deal. That's what Hungry Johnny is like for me, and, no doubt, for Native children who go to community feasts. I imagine Hungry Johnny will be much loved by Ojibwe children who will spot more than I did. What a treat!

Hungry Johnny is published by Minnesota Historical Society Press. A new book, its copyright is 2014. I highly recommend it. When you (parent/teacher/librarian) reads it to a child, you could also pull out a map and show them where Minnema and Ballinger are from: Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe.

The author of Hungry Johnny is Cheryl Minnema. She's Ojibwe, and so is the illustrator, Wesley Ballinger. And the story? It is about an Ojibwe kid. Named Johnny. Who is--as the title suggests--hungry!

When the book opens, Johnny is outside playing, but his tummy growls. He's hungry, and heads inside where his grandma is making wild rice. He spies that plate of sweet rolls on the table and makes a beeline for it, but she tells him "Bekaa, these are for the community feast." The word 'bekaa' is in bold on the page. It is one of several Ojibwe words in Minnema's book. Bekaa, by the way, means 'wait.'

As the cover demonstrates, Johnny lives in a modern home. His grandma, in jeans, sweater, and a ball cap, is at an electric stove, and as Johnny plods to another room, we see hardwood floors and photographs on the wall. When his grandmother tells him it is time to go, he leaps off the couch. He wants to eat, eat, eat! As they drive to the community center, he sings "I like to eat, eat, eat. I like to eat, eat, eat."

I've not said anything about a word that appears in the two paragraphs directly above this one. Community. There is a community feast at the community center. Such gatherings and spaces are common across the U.S. and Canada. It is one of the many ways that Native people maintain our traditions and relationships with each other.

At the center, Johnny has to wait again. An elder says a "very l-o-n-g prayer." Perfect! That is exactly what happens. As a kid, it seemed to me forever, too, waiting for elders to finish praying. But, wait we did, and so does Johnny. I gotta share a photo of that page:

See the elder's vest? That particular page highlights Ballinger's connections to his Ojibwe community. That is Ojibwe beadwork--the very kind that Minnema is known for! Here's a photo of some of her exquisite work:

Back to the story...

Elders eat first, so Johnny has to wait. His grandma waits with him, telling him to be patient. He wonders why she's not eating with the elders, and she explains she is a "baby elder" that is "too young to be old and too old to be young."

When Johnny and his grandma are finally at the table, he is crestfallen because the plate of rolls is empty. It is, however, a feast, and another plate of them is brought to the table. Just then, Johnny sees Katherine (an elder) arrive, and calls her over to take his seat. He isn't glum in calling to her. He understands that elders receive special treatment.

Course, this is a community with elders who pay attention to young ones, so, Katherine invites him to sit on her lap. Johnny finally gets his sweet roll.

There's a lot that I like about Hungry Johnny. The Ojibwe words, the teachings imparted, and, Ballinger's art. In 2000, Simms Taback won the Caldecott Medal for Joseph Had a Little Overcoat. I was teaching undergraduates that year in the College of Education. The Jewish students in my class pored over it, pointing to things in the illustrations that affirmed Jewish culture. I didn't notice them, but the students did, and it mattered to them a great deal. That's what Hungry Johnny is like for me, and, no doubt, for Native children who go to community feasts. I imagine Hungry Johnny will be much loved by Ojibwe children who will spot more than I did. What a treat!

Hungry Johnny is published by Minnesota Historical Society Press. A new book, its copyright is 2014. I highly recommend it. When you (parent/teacher/librarian) reads it to a child, you could also pull out a map and show them where Minnema and Ballinger are from: Mille Lacs Band of Ojibwe.